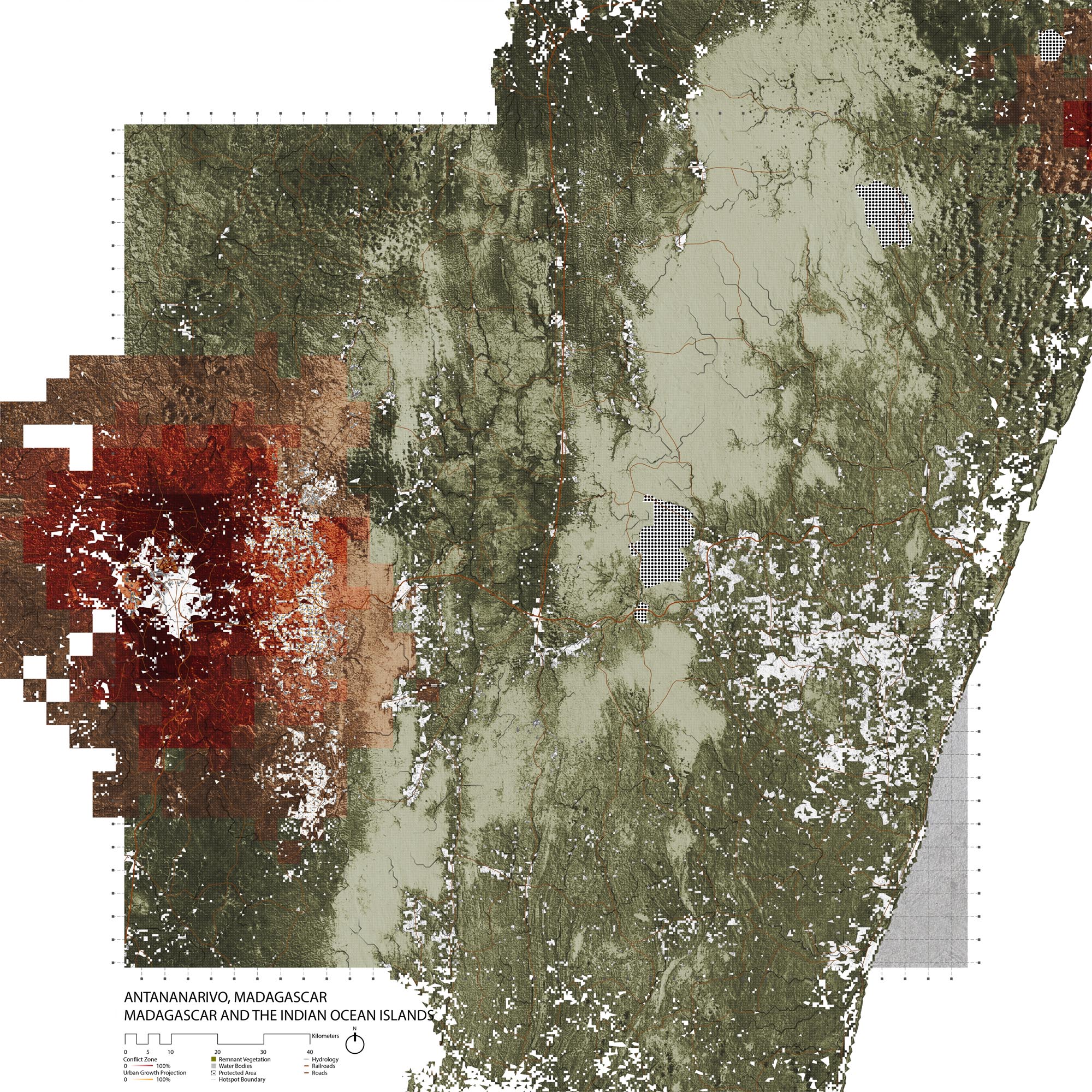

Antananarivo, Madagascar

- Global Location plan: 18.88oS,47.51oE [1]

- Population 2015: 2,610,000

- Projected population 2030: 5,073,000

- Mascot Species: Ring-tailed Lemur (Lemur catta): endangered

- Crops: mostly rice; but also potato, cassava, maize and vegetables[2]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Gephyromantis tschenki

- Cophyla karenae

- Stumpffia tridactyla

- Boophis rappiodes

- Boophis idae

- Mantella milotympanum

- Boophis pauliani

- Boophis pyrrhus

- Plethodontohyla alluaudi

- Mantella aurantiaca

- Blommersia angolafa

- Blommersia dejongi

- Boophis andrangoloaka

- Boophis andrangoloaka

- Boophis rhodoscelis

- Boophis calcaratus

- Boophis entingae

- Boophis fayi

- Boophis boehmei

- Boophis luciae

- Boophis goudotii

- Boophis popi

- Boophis roseipalmatus

- Boophis roseipalmatus

- Boophis madagascariensis

- Boophis madagascariensis

- Boophis elenae

- Boophis spinophis

- Gephyromantis boulengeri

- Heterixalus betsileo

- Heterixalus madagascariensis

- Boophis burgeri

- Boophis feonnyala

- Mantella betsileo

- Mantella madagascariensis

- Mantella nigricans

- Guibemantis albolineatus

- Mantidactylus argenteus

- Gephyromantis asper

- Mantidactylus biporus

- Mantidactylus femoralis

- Guibemantis flavobrunneus

- Mantidactylus guttulatus

- Gephyromantis luteus

- Mantidactylus mocquardi

- Gephyromantis ventrimaculatus

- Cophyla grandis

- Plethodontohyla bipunctata

- Plethodontohyla notosticta

- Plethodontohyla tuberata

- Scaphiophryne madagascariensis

- Mantella ebenaui

- Mantella crocea

- Stumpffia kibomena

- Cophyla karenae

- Anodonthyla vallani

- Mantella ebenaui

- Anodonthyla pollicaris

- Gephyromantis eiselti

- Guibemantis methueni

- Guibemantis methueni

- Guibemantis bicalcaratus

- Gephyromantis sculpturatus

- Gephyromantis thelenae

- Boophis sibilans

- Guibemantis depressiceps

- Cophyla tuberifera

- Mantidactylus lugubris

- Anilany helenae

- Mantella baroni

- Mantella pulchra

- Gephyromantis moseri

- Boophis lichenoides

- Aglyptodactylus madagascariensis

- Aglyptodactylus inguinalis

- Guibemantis timidus

- Mantidactylus ulcerosus

- Mantidactylus zipperi

- Spinomantis peraccae

- Dyscophus antongilii

- Mantidactylus aerumnalis

- Boophis opisthodon

- Mantidactylus charlotteae

- Rhombophryne coudreaui

- Heterixalus rutenbergi

- Boophis erythrodactylus

- Boophis albilabris

- Boophis albipunctatus

- Boophis ankaratra

- Boophis bottae

- Boophis liami

- Boophis luteus

- Boophis luteus

- Boophis marojezensis

- Boophis microtympanum

- Boophis picturatus

- Boophis reticulatus

- Boophis rufioculis

- Boophis solomaso

- Boophis tasymena

- Boophis tephraeomystax

- Boophis viridis

- Mantella cowanii

- Mantidactylus aerumnalis

- Spinomantis aglavei

- Mantidactylus albofrenatus

- Mantidactylus betsileanus

- Mantidactylus betsileanus

- Blommersia blommersae

- Mantidactylus brevipalmatus

- Gephyromantis cornutus

- Mantidactylus curtus

- Blommersia domerguei

- Spinomantis fimbriatus

- Blommersia grandisonae

- Guibemantis kathrinae

- Blommersia kely

- Guibemantis liber

- Mantidactylus majori

- Gephyromantis malagasius

- Mantidactylus melanopleura

- Mantidactylus opiparis

- Mantidactylus pauliani

- Spinomantis phantasticus

- Guibemantis pulcher

- Guibemantis punctatus

- Blommersia sarotra

- Guibemantis tornieri

- Mantidactylus zolitschka

- Mantidactylus grandidieri

- Gephyromantis redimitus

- Anodonthyla boulengeri

- Dyscophus guineti

- Paradoxophyla palmata

- Cophyla barbouri

- Cophyla pollicaris

- Rhombophryne coronata

- Plethodontohyla inguinalis

- Plethodontohyla mihanika

- Plethodontohyla ocellata

- Scaphiophryne boribory

- Scaphiophryne marmorata

- Stumpffia grandis

- Stumpffia tetradactyla

- Boophis mandraka

- Heterixalus punctatus

- Aglyptodactylus inguinalis

- Boophis williamsi

- Mantidactylus cowanii

- Boophis guibei

- Mantidactylus alutus

- Scaphiophryne spinosa

- Ptychadena mascareniensis

Mammals

- Eulemur albifrons

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Microcebus gerpi

- Microgale thomasi

- Microgale gracilis

- Microgale longicaudata

- Microgale parvula

- Microgale principula

- Mops midas

- Nesomys rufus

- Phaner furcifer

- Propithecus diadema

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Microgale gymnorhyncha

- Microgale drouhardi

- Microgale fotsifotsy

- Microgale majori

- Microgale soricoides

- Microgale taiva

- Microgale cowani

- Microgale talazaci

- Taphozous mauritianus

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Myzopoda aurita

- Scotophilus robustus

- Neoromicia robertsi

- Chaerephon atsinanana

- Nesomys audeberti

- Lepilemur betsileo

- Cheirogaleus crossleyi

- Eliurus ellermani

- Microcebus lehilahytsara

- Eliurus petteri

- Miniopterus sororculus

- Monticolomys koopmani

- Microcebus simmonsi

- Eulemur fulvus

- Eupleres goudotii

- Peponocephala electra

- Tursiops truncatus

- Cryptoprocta ferox

- Rousettus madagascariensis

- Eulemur rubriventer

- Stenella longirostris

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Hipposideros commersoni

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Pipistrellus raceyi

- Neoromicia matroka

- Neoromicia melckorum

- Gymnuromys roberti

- Grampus griseus

- Eidolon dupreanum

- Eulemur fulvus

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Hapalemur griseus

- Oryzorictes hova

- Miniopterus manavi

- Hemicentetes nigriceps

- Voalavo antsahabensis

- Orcinus orca

- Setifer setosus

- Miniopterus gleni

- Miniopterus ambohitrensis

- Miniopterus egeri

- Mops leucostigma

- Cheirogaleus major

- Limnogale mergulus

- Indri indri

- Hemicentetes semispinosus

- Microgale dobsoni

- Eliurus webbi

- Cheirogaleus sibreei

- Daubentonia madagascariensis

- Lepilemur mustelinus

- Microgale pusilla

- Eliurus tanala

- Fossa fossana

- Lagenodelphis hosei

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Tenrec ecaudatus

- Varecia variegata

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Delphinus capensis

- Paremballonura atrata

- Eliurus grandidieri

- Salanoia concolor

- Indopacetus pacificus

- Suncus murinus

- Microgale jobihely

- Miniopterus majori

- Galidictis fasciata

- Prolemur simus

- Stenella attenuata

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Kogia sima

- Galidia elegans

- Feresa attenuata

- Propithecus coronatus

- Suncus etruscus

- Allocebus trichotis

- Myotis goudoti

- Avahi laniger

- Brachyuromys betsileoensis

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Brachyuromys ramirohitra

- Brachytarsomys albicauda

- Kogia breviceps

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Eliurus majori

- Hapalemur griseus

- Mormopterus jugularis

- Pteropus rufus

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands hotspot exemplify evolution on islands in isolation. Rates of endemism are extraordinary – particularly high for mammals, plants, and reptiles – and not only at the species level but also at higher taxonomic levels (e.g. families). [3]

Species statistics [4]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

>11,200 |

~90% |

At least 2,500 more to be described |

|

Birds |

503 |

~60% |

|

|

Mammals |

211 (land species) |

~95% |

- New lemurs and small mammals continue to be discovered at a rapid rate. - Rich in bat diversity. |

|

Reptiles |

457 |

96% |

- Vital areas for 5 of the 7 marine turtles in the world |

|

Amphibians |

309 |

~100% (except one species) |

|

|

Fishes |

2,086 |

|

- Diverse in sharks and skates. - Heavily dependent on coral reefs. - the Critically Endangered “living fossil” coelacanth ( Latimeria chalumnae ) |

|

Invertebrates |

5,800 |

86% |

2,500 pending description |

In the poorest countries – the Comoros and Madagascar – the main threats are linked to poverty and underdevelopment. Rural populations experiencing significant growth are exerting increasing pressure on the ecosystems. Deforestation is one of the largest problems; Madagascar’s natural forest cover has already been reduced to about 12 percent. In addition, farmers practicing the traditional agricultural technique (known as

tavy

, a slash-and-burn method) are forced to shorten cultivation cycles and expand to less suitable areas, causing severe land degradation. Other major threats include hunting and bushmeat consumption, wildlife trafficking (enforcement of CITES lacking), and invasive species (especially devastating to islands). Climate Change hugely affects the hotspot due to coral bleaching. Some studies estimate that the Indian Ocean corals may completely vanish within 20 to 50 years.

[5]

CEPF’s initial US$5.6 million investment focused exclusively on Madagascar. In the current phase – US$9.54 million between 2015 and 2020 – the funds will encourage conservation ideas that show the link between biodiversity and sound development.

[6]

Madagascar Subhumid Forests

The Madagascar Subhumid Forests ecoregion experienced species extinction on a large scale, right after the first arrival of humans some 20,000 years ago; and it is at high risk of further extinction in the near future. The ecoregion is scattered in several “islands” of montane humid forest throughout the central highlands of Madagascar, plus some wetlands, lakes, and the “tapia” forest. To the east, the subhumid forests meet moist forests in the lowland ecoregion around 800 m elevation, and to the west they transition into the dry deciduous forest ecoregion at 600 m. The remaining habitat is surrounded by huge expanses of secondary grasslands and exotic tree plantations, the result of human activity. Numerous forms of mammals are strictly endemic to the ecoregion, most notably various types of lemurs. Endemism is also high amongst reptiles and amphibians, including several chameleons. The original habitat of the Madagascar subhumid forests are extremely fragmented. Despite the establishment of some protected areas, lack of resources, inadequate training, limited personnel, and the absence of clear management plans all cause concerns. The main threats to biodiversity in the ecoregion are encroaching agriculture, growing population, siltation, pollution, and increased anthropogenic fires. [8] Today, 6 percent of the ecoregion is protected, which has a 3.71 percent terrestrial connectivity. [9]

Environmental History

The first settlers on Madagascar were most likely Polynesians, who arrived on the island 1,000 to 2,000 years ago causing the extinction of species like Elephant Birds ( Aepyornithidae ). Africans later arrived to the island from the mainland, resulting in the formation of diverse ethnic groups throughout the island. [10]

Antananarivo, or “Land of a thousand,” received its name when King Andrianjaka settled in the area with 1,000 soldiers in the early 17th century. Through successive leaders, the city grew and protected itself by banning foreigners in the 1800s. From 1895 to 1960, France occupied Antananarivo, then renamed Tananarive, connecting it to the coast with railroads, and restructuring its layout and while preserving historic landmarks. [11]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Ineffective waste management is a major obstacle to the sustainable development of Antananarivo. Indeed, wastewater is uncontrollably discharged into nature and only 37% of solid household waste is collected. Additionally, 42% of households in low-income neighborhoods dispose of their solid waste in the streets or in marshlands directly. [12]

In terms of air pollution, Antananarivo is among the worst cities in the world, with more than 0.50 μg/m3 of led and 0.07mg/m3 of other suspended substances including dust and exhaust gas. [13]

Additionally , woodlands in the area have been alarmingly depleted; although the average deforestation rate in the Analamanga region was five times lower from 2005 to 2010 than it was from 1990 to 2000, forest cover only occupied 3.06% of the region in 2010. [14] . P rotected areas near the city are insufficient and poorly guarded, and the uncontrolled expansion of the city poses a major threat to neighboring ecosystems. [15] Satellite imagery reveals the densification of peri-urban areas and far-stretching agricultural areas over the past 15 years. Residential areas have been expanding along existing and new roads, onto grasslands and farmlands. [16]

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

With a density of 11,900/km2, Antananarivo is growing largely informally, given that 30% of its urban neighborhoods are informal or non-structured. [17]

The UN-Habitat Antananarivo Urban Profile reveals that the city is overpopulated, leading to higher demands for land than is available, and thus to an increase in informal developments and in land use conflicts. Informal land use seems so rooted in the local lifestyle that the city holds little authority over land acquisition and occupation of both private and public lands. Informal growth is further stimulated by the extreme prices of real estate, which make acquisition a luxury. [18]

Informal structures represented 70% of built homes in 2010 and a quarter of housing in the city was located in precarious slums. The Urban Profile report attributes the causes of this situation to the slowness of administrative processes, to settlements that precede any planning, and to the lack of land-planning tools. The report further explains that Antananarivo lacks short-term and long-term housing policies and does not have the sufficient resources for demolition operations. [19]

Governance

Madagascar is divided into 22 administrative regions, each of which is made up of districts. Antananarivo is mainly located in the Analamanga region. The west portion of the city is located in the Antananarivo-Atsimondrano district, the northeast in the Antananarivo-Avaradrano district and the southeast Antananarivo-Renivohitra.

Marc Ravalomanana, former president of Madagascar, was deposed during a coup in 2009. The country has since returned to stable democracy, and his wife Lalao Ravalomanana is the mayor of the Urban Commune of Antananarivo (CUA), under the presidency of Hery Rajaonarimampianina. [20]

City Policy/Planning

The second of three strategic axes in the Regional Development Plan of Alamanga aims to create and promote socially-based economic growth, including the “conservation of ecological potential and richness.” The Plan suggests reforestation in sites that are to be identified as well as the involvement of local communities to train professionals. It also addresses the need to responsibilize Fokontany leaders, or local community leaders, to curb wildfires. The plan also mentions the need to expand conservation areas, to promote ecotourism and to improve awareness on biodiversity issues. [21]

The plan also addresses the need to improve awareness on environmental protection and to promote erosion control through anti-erosion systems and agroforestry. [22]

The Antananarivo Urban Profile sets several priorities for land use management, including the reinforcement of the city’s technical capacity and the creation of an urban land register, of an urban land policy, and of land reserves in the outskirts of the capital. As for informal settlements, the document focuses on defining housing and development policies, producing construction documents, restructuring underprivileged settlements, and helping struggling households through social housing and by giving them access microcredits. [23]

The City has not updated its zoning since 1963 but formulated a Director Plan for Urbanism in 2017. [24]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

The 2015-2025 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) recognizes some positive aspects of the present conservation. For instance, Madagascar successfully tripled the area of protection sites following the 2003 Durban World Parks Congress, reaching 6 million ha in 2010. The plan also acknowledges existing efforts to create biological corridors, to restore threatened endemic species, and to implement conservation programs. [25]

However, the current biodiversity problems in Madagascar remain as the focus of the Plan. The document lists 12 guidelines (namely the integration of biodiversity conservation into social and economic development) as an essential component of sustainable planning. The guidelines also emphasize a collaborative and participatory approach, to improve and share the benefits reaped from the sustainable usage of biodiversity resources. Combined with awareness-raising on biodiversity issues, such a way of involving citizens would help develop a sense of responsibility. The plan addresses the need to protect vulnerable communities that depend on natural resources, and to use conservation to improve people’s well-being. Finally, the guidelines address the need for improved biodiversity knowledge, through research, and for sustainable funding methods. [26]

The Plan is structured by five goals, each focusing on a different aspect of conservation. The first aims to control the causes of biodiversity loss. Thus, by 2025, awareness will reach all policy makers and 65% of the Malagasy population, and incentives like Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) will be developed. By then, biodiversity conservation should be integrated into socio-economic development through the formulation of rational management plans of resources. [27]

The second goal describes the need to reduce more direct pressures on ecosystems. This section of the plan aims to decrease the rate of habitat degradation and fragmentation through the mapping and identification of high biodiversity habitats and the empowerment of stakeholders. By 2025, agriculture, aquaculture and forestry zones should be supervised and managed sustainably, pollution should be significantly reduced, and alien or invasive species should be controlled. [28]

The third goal puts emphasis on safeguarding existing ecosystems, especially by improving the status of endangered species and maintaining genetic diversity of domesticated species. Nevertheless, Madagascar also sets the target to protect 10% of its terrestrial area by 2025, thus negating its previous commitment to the Aichi target of 17% by 2020. [29]

The fourth goal speaks of enhancing and sharing the benefits provided by ecosystems, by restoring ecosystems that contribute to the livelihood and wellbeing of locals and by strengthening ecosystem resilience to climate change through restoration of 15% of degraded ecosystems. [30]

The fifth goal addresses the application of conservation measures, in particular the adoption of a political and legal instrument for the implementation of the NBSAP. The goal also includes targets to create initiatives to secure local conservation efforts, to share biodiversity knowledge with stakeholders, and to improve human and financial resources for the implementation of the plan. [31]

National

More general national planning documents like the Madagascar 2030 Growth and Transformation Plan barely mention biodiversity. In this example, ecosystems are mentioned as a potential resource for economic growth, whose preservation could lead to profits in tourism. [32]

Some documents like Approach for the Planification of Forest Zones and Other Significant Ecological Regions in Madagascar offer a base for national and regional planning that does not seem to have been used for by policymakers. [33]

The Malagasy National Office for the environment operates to reduce ecosystem degradation, to create policies for protection, and to manage information linked to conservation. [34]

The within the Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, the Unity of Coordination of Environmental

Protected Areas Near City

Projects raises funds to finance projects for environmental management and conservation. The Ministry also manages the protected area system of the country. It seeks to ensure the representativeness and connectivity of the network and to protected species outside of it, as well as to conserve important habitats and viable populations of keystone species. [35]

Some of these areas are located near the capital: Ambohitantely Reserve (56km2), Andasibe-Mantadia National Park (155 km2), Lemur Park (5ha) and Tsarasaotra parc (25ha).

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

Among the international organizations working in Madagascar, the United Nations Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) leads its Emission Reduction Program (ER-P) over 62,236km2 zone . The program includes forest inventory, deforestation analysis, the development of a Social and Environmental Strategic Framework (CGES), of Forest Emission Reference Levels, a Forest Surveillance National System and a Complaint Management Mechanism. In the future, the program will seek to develop a profit sharing mechanism and strengthen partnerships with the private sector.

In addition to large international organizations, non-governmental organizations are very active in Madagascar to reduce biodiversity loss. For instance, the Madagascar Biodiversity Network (ReBioMa) seeks to improve conservation planification in the country, especially through information management, like the creation of an atlas on the state of the Malagasy forest cover, or of a summary of Malagasy species. [36]

With a similar focus on administration, a cooperation between USAID and the Traffic organization led to the formulation of a Framework for the Evaluation of the Legality of Forest Operations, of the Transformation and Commercialization of Woodlands. [37] Another international collaboration, project “Low Space No Space” involving the French Ile-de-France region, encourages citizens of Antananarivo to grow their own crops using every available space and tool, in order to increase food security and reduce pressures on intact ecosystems. [38]

More specific operations focus on particular species, including the Darwin Initiative which has led multiple conservation projects in the country since 1995 with species like the near-extinct Madagascar Pochard ( Aythya innotata ) and chameleons. [39] The Wildlife Conservation Society has focused on some lemur species like the Silky Sifaka ( Propithecus candidus ) and the Indri ( Indri indri ). [40]

Public Awareness

Awareness on biological diversity seems quite low in Madagascar, and conservation concerns certainly aren’t as much of a priority as problems like food security. Even environmental issues that are generally more recognized than biodiversity loss, such as climate change and pollution, are not perceived as a major threat by the citizens of Antananarivo.

Conclusion

The challenges that the Analamanga Region is facing in meeting the Aichi 2020 target bear witness to the informal nature of the region’s densification. Indeed, the success of biodiversity conservation efforts around Antananarivo foremost rely on the city’s ability to gain control over its land use. Writing and enforcing policies against harmful practices constitute the next major priority for the region. Among such practices, deforestation continues to threaten biodiversity despite having decreased significantly in the past two decades, and mining, illegal logging and intensive agriculture only further weaken local ecosystems.

Although biodiversity planning exists on a national level, the local government is not as committed to conservation or to planning for sustainable growth; its zoning code has not been updated in over 50 years.

[2] CAPFIDA, “Rapport d’analyse Regionale, Region Analamanga,” https://www.capfida.mg/pi/www.capfida.mg/km/cosop/Rapports_regionaux/analamanga.html (accessed June 6, 2018)

[3] CEPF. “Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/madagascar-and-indian-ocean-islands.

[4] CEPF. “Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands - Species.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/madagascar-and-indian-ocean-islands/species.

[5] CEPF. “Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands - Threats.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/madagascar-and-indian-ocean-islands/threats.

[6] CEPF. “Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/madagascar-and-indian-ocean-islands.

[7] Kathleen M. Muldoon & Steven Michael Goodman, “Primates as Predictors of Mammal Community Diversity in the Forest Ecosystems of Madagascar,” PLOS ONE (September 3, 2015)

[8] WWF. “Southern Africa: Central Madagascar | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/at0118.

[9] “Madagascar Subhumid Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/30118.

[10] Wired, “Madagascar's first residents could have arrived with a shipwreck,” http://www.wired.co.uk/article/madagascar-population-origins (accessed June 5, 2018)

World Wildlife Fund, “Southern Africa: Central Madagascar,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/at0118 (accessed June 5, 2018)

Wild madagascar, “People,” http://www.wildmadagascar.org/people/ (accessed June 5, 2018)

[11] http://www.blackpast.org/gah/antananarivo-madagascar-1600s

[12] UN Habitat, “Madagascar: Profil Urbain d’Antananarivo,” 2012

[13] UN Habitat, “Madagascar: Profil Urbain d’Antananarivo,” 2012

[14] Madagascar Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan,” 2015

[15] UN Habitat, “Madagascar: Profil Urbain d’Antananarivo,” 2012

[16] EARTH

[17] Government of Madagascar, “Plan National de Developpement 2015-2019,” 2015

[18] UN Habitat, “Madagascar: Profil Urbain d’Antananarivo,” 2012

[19] UN Habitat, “Madagascar: Profil Urbain d’Antananarivo,” 2012

[21] Région Analamanga, “Plan Regional de Developement,” 2010

[22] Région Analamanga, “Plan Regional de Developement,” 2010

[23] UN Habitat, “Madagascar: Profil Urbain d’Antananarivo,” 2012

[24] UN Habitat, “Madagascar: Profil Urbain d’Antananarivo,” 2012

Direction Générale de la Gestion Financière du Personnel de l'Etat, “Antananarivo: Lancement Officiel du PUDI en Mars” (January 2017), http://www.dggfpe.mg/index.php/2017/01/16/antananarivo-lancement-officiellement-pudi-mars/

[25] Madagascar Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan,” 2015

Joanna Durbin, “Madagascar’s new system of protected areas – Implementing the ‘Durban Vision,’”

[26] Madagascar Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan,” 2015

[27] Madagascar Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan,” 2015

[28] Madagascar Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan,” 2015

[29] Madagascar Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan,” 2015

[30] Madagascar Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan,” 2015

[31] Madagascar Ministry of the Environment, of Ecology and of Forests, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan,” 2015

[32] Ministère Auprès de la Présidence en Charge de l'agriculture de de l’Elevage, “Plan de Croissance et de Transformation: vision de developpement de Madagascar à l’horizon 2030,” 2018

[33] US Forest Service, United States Agency for International Development & Conservation International, “L’Approche pour la Plannification des Zones Forestières et des Autres Aires Ecologiquement Significatives a Madagascar,” 2003

[34] “Office National pour L’Environnement, “A propos,” https://www.pnae.mg/a-propos (accessed June 26, 2018)

[35] Ministère de l’environnement, de l’écologie et des forrêts, “Objectifs système d’aires protégées de Madagascar” http://www.ecologie.gov.mg/introduction-sur-le-sapm/objectifs/ (accessed June 5, 2018)

Unité de Coordination des Projets Environnementaux, “Présentation,” http://www.ecologie.gov.mg/ucpe/ (accessed June 5, 2018)

[36] Rebioma, “About Us,” http://www.rebioma.net/index.php/rebioma/about-us (accessed June 5, 2018)

Rebioma, “Species,” http://www.rebioma.net/index.php/en/biodiversite/species (accessed June 5, 2018)

[37] Julien Noël Rakotoarisoa et al., “Cadre pour l'Évaluation de la Légalité des Opérations Forestières, de la Transformation et de la Commercialisation des Bois,” 2016

[38] RUAF Foundation, “Projet Agriculture Urbain ‘low space no space,’” http://www.ruaf.org/publications/projet-agriculture-urbain-low-space-no-space-antananarivo-madagascar (accessed June 5, 2018)

[39] Darwin Initiative, “Country, Madagascar,” http://www.darwininitiative.org.uk/project/location/country/madagascar/ (accessed June 5, 2018)

[40] WCS Madagascar, “Conservation Science,” https://madagascar.wcs.org/Initiatives/Biodiversity-and-Conservation-Science.aspx (accessed June 5, 2018)