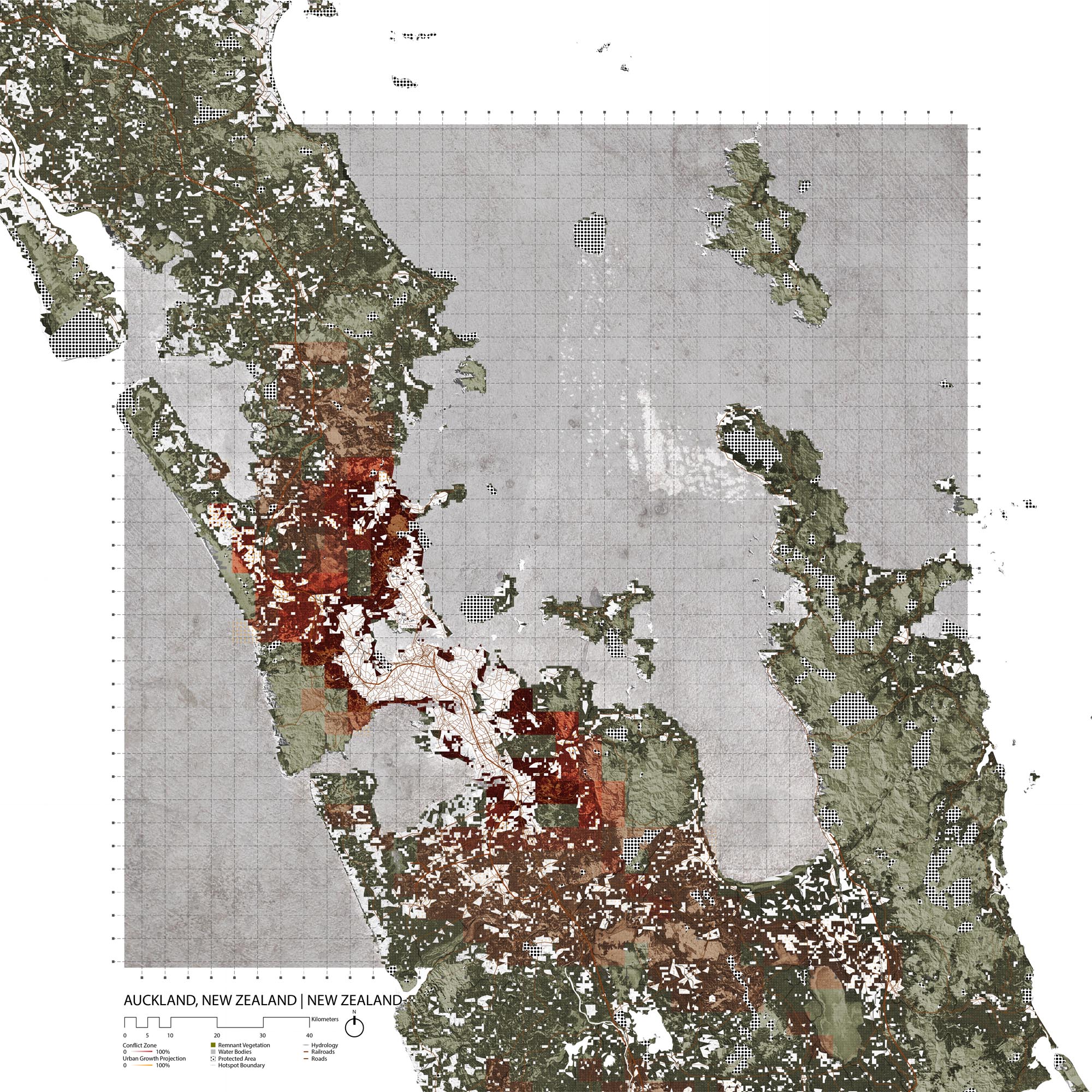

Auckland, New Zealand

- Global Location plan: 36.85oS, 174.76oE

- Population 2015: 1,344,000

- Projected population 2030: 1,574,000

- Mascot Species: the Northern Brown Kiwi (Apteryx mantelli) is vulnerable and the New Zealand Christmas Tree (Diporochaeta obtusa) is in steep decline.

- Crops: mostly potatoes and onions, but also wine grapes, maize grains, kiwi , buttercup squash, and avocado.[1]

Endangered species

Mammals

- Tasmacetus shepherdi

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Mesoplodon ginkgodens

- Mesoplodon grayi

- Mesoplodon hectori

- Mesoplodon layardii

- Mustela erminea

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Tursiops truncatus

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Lagenorhynchus obscurus

- Mus musculus

- Grampus griseus

- Chalinolobus tuberculatus

- Chalinolobus tuberculatus

- Chalinolobus tuberculatus

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Orcinus orca

- Hyperoodon planifrons

- Berardius arnuxii

- Arctocephalus forsteri

- Cephalorhynchus hectori

- Delphinus delphis

- Mesoplodon traversii

- Lepus europaeus

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Delphinus capensis

- Eubalaena australis

- Lissodelphis peronii

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Kogia sima

- Mesoplodon bowdoini

- Caperea marginata

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Balaenoptera physalus

- Globicephala melas

- Kogia breviceps

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Mystacina tuberculata

- Rattus exulans

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The New Zealand biodiversity hotspot covers the country’s three main islands (North Island, South Island, and Stewart Island) and several surrounding islands (the Chatham, Kermadec, and Subantarctic). Also included are Lord Howe and Norfolk islands; both Australian territories. Ranging in latitude from subtropical to subantarctic, New Zealand is of varied landscapes – rugged mountains, rolling hills, active volcanoes, and wide plains. Largely isolated for millions of years, this hotspot preserves uniquely evolved flora and fauna. [2]

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~3,400 |

~56% |

- Kauri ( Agathis australis ) [4] |

|

Birds |

~200 |

~44% |

- giant species all went extinct after the arrival of Polynesians - 20 species extinctions since 1500 - Vulnerable [5] northern brown kiwi ( Apteryx mantelli ), roams near Auckland - most diverse seabird community (80 breeding species); 75 percent of all penguin species |

|

Mammals |

Only 2 native bats |

100% |

- Vunlerable New Zealand lesser short-tailed bat ( Mystacina tuberculata ), Critically Endangered New Zealand Greater Short-tailed Bat ( Mystacina robusta ) |

|

Reptiles |

~40 |

100% |

- geckos and skinks |

|

Amphibians |

DD |

DD |

- primitive frog family Leiopelmatidae |

|

Freshwater Fishes |

~40 |

~25% |

|

|

Invertebrates |

DD |

DD |

- widespread occurrence of gigantism |

Although humans (Maoris) first arrived in New Zealand relatively late – only around 700 to 800 years ago – the effects still have been extensive. Greater threats were the introduction of alien species (especially predatory mammals) by the European settlers in the 19 th century, which continues to devastate the local biodiversity. Other major issues include hunting, deforestation, and wetland drainage. [6]

Northland Temperate Kauri Forest

Auckland City is located in the Northland Temperate Kauri Forest, the northernmost ecoregion of New Zealand. The Northland Temperate Kauri Forest ecoregion comprises the northern portion of New Zealand’s North Island and was once dominated by the gigantic kauri ( Agathis australis ) trees. Annual rainfall averages from 1,000 to 2,500 mm. Kauri trees can grow both in monotypic stands and in mixed forests. The silvery tree fern ( Cyathea dealbata ) and kauri grass ( Astelia trinervia ) are common in the understory. Plant endemism is highest in the northern Northland province. The Firth of Thames, located in this ecoregion, is one of the country’s most important coastal habitats for large populations of both resident and migratory seabirds. [7]

European settlement resulted in large-scale kauri harvesting, logging, gum-tapping, bushfires, and the conversion of wetlands for farming and livestock grazing. By the end of the 20 th century, only 8 percent of the original wetlands remained. Only 6 percent of the Kauri forests are left. Today, all of the remaining kauri forests on Crown lands are under protection by the Department of Conservation, and past crises have largely been mitigated. Nowadays the biggest threats are natural senescence and browsing by brush-tailed possums ( Trichosurus vulpecula ). However, the government needs to continue its predator control since birds are still seriously predated by introduced cats and other mammals. There are also weeds spreading from gardens or farms. [8] At present, 12 percent of the ecoregion is protected (the largest protected area being Coromandel State Forest, a Conservation Park designated in 1928), and 4.71 percent has terrestrial connections. [9]

Environmental History

New Zealand has been occupied by Mauri since as early as 1200 . The Auckland area’s rich soil and two waterfronts made it an ideal location for settlement. [10] T he first European settle rs arrived in 1642 and the i slands fell under British rule in 1840. Today, the protection of Mauri rights and culture is closely tied with the protection of nature, as made apparent in 2017 when a river was given the same rights as a person. [11]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Auckland has many environmental issues, especially air pollution due to carbon dioxide emissions and water pollution from industrial waste. A gricultur al practices in the surrounding region have led to soil compaction , pollution , and soil erosion. [12]

Although twenty-seven percent of indigenous forest cover is intact in the Auckland region, it is concentrated in the Huana and Waitakere Ranges. Wooded areas are often interrupted by farmland, developments, and quarries, resulting in highly fragmented forest cover with an average patch size of 18ha. The Auckland region is home to 20% of New Zealand’s terrestrial vertebrate fauna and 19% of its threatened flora. A lien species -- including deer, pigs, goats, livestock and weed s-- represent the biggest threats to biodiversity in the region. [13]

The New Zealand Department of Conservation delineates 268 Ecological Districts (ED) that each have specific conservation issues and priorities . [14] Of the 12 Ecological Districts in the Auckland Region, the Manukau ED is the most depleted with only 1.6% of land occupied by native vegetation, 85% of which occurs in patches that are smaller than 5Ha. [15] The 2002 district plan of Manukau addressed the protection of native flora in part as a response to the loss of 10.6% of indigenous cover between 1996 and 2001. [16] The district has since come under the authority of the Auckland Council which tackles biodiversity issues in its Unitary Plan.

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Between July 2016 and June 2017, Auckland’s population grew by 2.6%. The highest growth rate of Auckland’s local board areas occurred in Waitemata, with 6.7%. Hibiscus and Bays, Papakura, Rodney, Upper Harbor and Waiheke are the next fast-growing areas with 2.9%-4.1% growth.

In Auckland, growth occurs in the form of formal developments, especially through the densification of existing urban centers and the conversion of rural areas to urban areas.

Governance

New Zealand is divided into 16 regions that are governed by local councils. The Auckland Region (4895km2) has been controlled by a single local government body-the Auckland Council-since 2010. The Council is headed by an elected mayor (governance arm) who appoint s a chief executive (operational and service delivery arm). [17] Since 2010, the Region has been divided into 13 wards that elect a total of 20 representatives to the Auckland Council. [18]

Governance Map of the North Island of New Zealand

City Policy/Planning

Development Plan

Auckland Pla n 2050, which was adopted in June 2018 , identifies six outcomes that define major development objectives for the city. The Homes and Places outcome is centered around the development of quality, affordable housing and accessible public areas. The Development Strategy of the Auckland Plan and the Auckland Urban Land Supply Strategy account for urban expansion into rural areas, with the designation of “Future Urban Areas,” and provide a detailed timeline of urban development . [19] The En vironment Outcome is described in greater detail below, under the Biodiversity Planning section.

Zoning

While the Auckland Plan 2050 focuses on long-term development goals, the Unitary Plan is the statutory zoning plan for Auckland that regulates land use. In terms of growth, the Unitary Plan focuses on dense development, and specifically on developing downtown Auckland, its waterfront, and some low density suburban towns like Pakuranga. The plan seeks to revitalize existing urban areas and favors land use conversion of rural areas into urban areas in place of developing native forest. However, aside from the Waitakere Forest and a few clusters in the South-East, the Unitary does not delineate substantial protected areas. [22]

The Unitary plan does however set concrete policies that contribute to protecting biodiversity. It seeks to minimize adverse effects of development on biodiversity and to offset them through restoration when negative consequences cannot be avoided. Most human activities that pose a threat to biodiversity are listed as “restricted discretionary activity.” For instance, the Unitary Plan prohibits the removal of trees more than 6m in height or 600mm in girth and the alteration of vegetation further than 1m from lawfully established structures. [23]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

The New Zealand Biodiversity Action Plan was originally submitted in 2000 and then revised in 2016. The plan is structured by five main goals. The second goal addresses reducing pressures on biodiversity, through successful pest management by 2020 ( with programs like the War on Weeds) and predator eradication by 2050. This section also mentions programs like the Kiwi Recovery Plan, which aims to increase the Kiwi population to 100,000 by 2030. The third goal concentrates on the safeguarding of ecosystems, species, and genetic diversity through land management, to achieve 1.3 million ha of “high level of ecological integrity” and 3.9 million ha of “ecological integrity,” which is defined in another Department of Conservation document as the “degree to which the physical, chemical and biological components (including composition, structure and process) of an ecosystem and their relationships are present, functioning and maintained close to a reference condition reflecting negligible ... anthropogenic impacts.” [24] This portion of the plan mentions cooperation with landowners to protect ecosystems, and the close-monitoring of 407 native New Zealand species. One example is the ground-breaking genome sequencing of the entire Kakapo population to determine breeding strategies and manage genetic diversity. The remaining three goals involve “mainstreaming biodiversity” in both society and the government, improving the advantages gained from conservation for everyone, and strengthening policy implementation. The N BSAP does not identify urbanization as a significant threat to biodiversity in New Zealand. [25]

National

In addition to efforts to abide by the Convention on Biological Diversity, New Zealand has established its own framework for conservation. Using statuses analogous to those listed by the IUCN, the New Zealand Threat Classification System (NZTCS) identifies threatened species status as Nationally Critical, Nationally Endangered, and Nationally Vulnerable. [26] Section is missing how th is system protects species it identifies as threatened under law .

The 2012 Indigenous Biodiversity Strategy develops eight objectives that support the many biodiversity agreements that New Zealand abides by. The objectives are focused on protected ecosystems types, long-term species recovery, support for Maori wellbeing, understanding and stewardship, information, integrated approach to conservation, and improvement of implementation. The document also provides methods of performance evaluation. [27]

Regional

The Environment and Cultural Heritage outcome of the Auckland 2050 Plan addresses multiple issues related to the environment: public involvement, respect of Maori culture, awareness and control of city growth, water management, and sustainable infrastructure. The plan mentions two sections that address biodiversity explicitly; the second focus area addresses environment restoration and the fourth environment protection. More concretely, the text tackles residual contamination, habitat restoration and creation, and extensive protected area programs. [28]

Biodiversity threats are tackled more indirectly in many other initiatives by the Auckland City Council including Low Carbon Auckland and Auckland Plan 2050’s commitments around water management and sustainable infrastructure.

One of these programs, the North-West Wild-Link, seeks to link the Hauraki Gulf to the Waitakere Ranges to allow safe travel corridors and breeding grounds for wildlife, especially birds. The plan consists mainly of pest control and planting of native flora. For instance, project Twin Streams has already led to the planting of 750,000 trees to stabilize the Waitakere Stream banks. Other projects include freeing Whangaparaoa Peninsula and Paremoremo-Albany of pests, regenerating wildlife in the Tuff Crater R eserve, and encouraging landowners to eradicate pests with Ark in the Park buffer zones. [29] Similarly, the Weiti Wild-Link aims to restore the banks of the Weiti river and protect the plants, fish and other wildlife that reside there. [30]

The 2009 Auckland Protection Strategy provides a very precise report on the status of Auckland Region’s Ecological Districts, as a framework for the New Zealand Nature Heritage Fund Committee to operate under . It assesses remaining native forest cover and defines ten priorities that focus on protecting threatened indigenous cover in a representative and sustainable manner. Eco-region specific sections determine local priorities for conservation. For instance, the Rodney District report suggests a focus on coastal ecosystems and Kauri forests. [31]

The Health of Auckland Report is a more recent document that supports the Auckland Plan 2050 by assessing the success of environmental policies. The report discusses the status of native flora and fauna, through broad assessments as well as case studies. Case studies include the rediscovery of the New Zealand Storm Petrel that was thought to be extinct for 108 years, the search for a cure to the Kauri dieback disease that has been spreading dangerously across the north of the country , and studies of how m icroorganism biodiversity is affected by soil macroporosity and low phosphorus levels due to soil compaction and excessive fertilizer use. The report on pest control reveals that despite significant pest-management success, certain weeds like gorse, radiata pine, tree privet and woolly nightshade continue to threaten native flora and fauna. [32]

More extensive pest control solutions are presented in the 2013 Weed Management Policy, whose sixth objective addresses the threat that weeds pose to native plant and animal species. [33] Concrete pest control programs seem to be thus far very successful. For instance, the Huana Project consisted in the application of “1080” (sodium fluoroacetate) to repel possums and rats, resulting in 0% prevalence of these species in the involved areas. The Auckland Council’s Pest and Weed Control have also identified pigs as likely carriers of Kauri dieback. [34]

A study conducted by Wendy A. Ruscoe, et al. shows that 1080 is considerably cheaper than thorough rat control and is quite effective, raising population levels of species like the Tree Wata and the Kokako. [35] However, Jay Ruffell & Raphael K. Didham argue that the use of 1080 only favors certain species and is only truly beneficial if paired with the reintroduction of locally extinct species. [36]

Local

Location-specific management plans like the Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan or the Tupuna Maunga Integrated Management Plan provide guidelines for biodiversity contribution on a more local level.

Protected Areas

Rangitoto Island Scenic Reserve and the Puhinui Reserve are two of the protected areas closest to Auckland City. Further out are the Waitakere Ranges Heritage Area and Huana Ranges National Park. The Auckland Council also manages the Whatipu Scientific Reserve and the Te Arai Park, which was purchased in 2008 explicit ly for conservation purposes. [38]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The New Zealand Trust for Conservation Volunteers initiates ecosystem restoration projects in the Auckland area. For instance, volunteers perform weed control in Little Shoal Bay or on Motuihe Island, sapling planting on the Motutapu Island, forest restoration over 200 ha along the La Trobe track, and many other undertakings in projects both offshore and inland. [39]

The Million Trees program has also greatly contributed to the restoration of forest cover in the Auckland Region. Although the focus of the project seems to be general “greening,” the program carefully plans for the planting of appropriate species, thus contributing to restoring indigenous forest cover. [40]

Similarly, Auckland Growing Greener is not exclusively centered around biodiversity, but its priority area three makes a significant contribution to conservation efforts, through the identification and protection of high-priority species in restoration projects, as well as the establishment of Waitawa and Te Arai Regional Parks. Growing Greener also includes threatened species protection and release programs, local ecology restoration, seed banking, and Regional Pest Management programs. [41]

The Treasure Islands Initiative seeks to further support pest eradication from islands in the Auckland Region, namely through awareness campaigns. [42]

New Zealand as a whole encourages biodiversity offsetting, or the restoration of habitat somewhere when it was damaged because of development somewhere else.

[1] Stats NZ, “Agricultural Production Statistics: June 2017,” https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/agricultural-production-statistics-june-2017-final (accessed June 26, 2018)

[2] CEPF. “New Zealand.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/new-zealand.

[3] CEPF. “New Zealand - Species.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/new-zealand/species.

[4] “Agathis Australis (Kauri) Description.” Accessed August 13, 2019. https://www.conifers.org/ar/Agathis_australis.php.

[5] “Northern Brown Kiwi.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 13, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[6] CEPF. “New Zealand - Threats.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/new-zealand/threats.

[7] WWF. “Northern Part of New Zealand’s North Island | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/aa0406.

[8] WWF. “Northern Part of New Zealand’s North Island | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/aa0406.

[9] “Northland Temperate Kauri Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/10406.

[10] Word Guides, “Auckland History Facts and Timeline,” http://www.world-guides.com/australia-continent/new-zealand/north-island/auckland/auckland_history.html (accessed June 12, 2018).

[11] BBC, “New Zealand profile - Timeline,” http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-15370160 (accessed May 24, 2018).

[12] Jamie Morton, New Zealand Herald, “Auckland’s Environment: Four Perspectives,” https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11914922 (accessed June 12, 2018)

[13] Auckland Council, “State of the environment and biodiversity,” http://temp.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/EN/planspoliciesprojects/plansstrategies/unitaryplan/Documents/Section32report/Appendices/Appendix%203.11.8.pdf (accessed June 12, 2018).

[14] https://www.doc.govt.nz/documents/science-and-technical/Ecoregions1.pdf

[15] Auckland Council, “State of the environment and biodiversity,” http://temp.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/EN/planspoliciesprojects/plansstrategies/unitaryplan/Documents/Section32report/Appendices/Appendix%203.11.8.pdf (accessed May 24, 2018).

[16] Manukau City Council, “Manukau Operative District Plan 2002,” 2002

Department of Conservation, “New Zealand’s remaining indigenous cover: recent changes and biodiversity protection needs” Science for Conservation , 284 (2008)

[17] Auckland Council, “Governance Manual,” http://governance.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/4-the-mayor-of-auckland/the-relationship-between-the-mayor-and-chief-executive/the-mayor-and-the-chief-executive/ (accessed May 24, 2018).

[18] Auckland Council, “About Wards,” https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/about-auckland-council/how-auckland-council-works/governing-body-wards-committees/wards/Pages/about-wards.aspx (accessed June 19, 2018)

[19] https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/auckland-plan/development-strategy/Pages/managed-expansion-into-future-urban-areas.aspx

https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/topic-based-plans-strategies/housing-plans/Documents/future-urban-land-supply-strategy.pdf

[20] https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/topic-based-plans-strategies/housing-plans/Documents/future-urban-land-supply-strategy.pdf

[21] https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/auckland-plan/development-strategy/Documents/map-18-ds-rural.pdf

[22] Auckland Council, “GeoMaps Public” https://geomapspublic.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/viewer/index.html (accessed June 13, 2018)

[23] Auckland Council, “Vegetation management and biodiversity , Section 32 report on the Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan,” 2013

[25] Department of Conservation, “New Zealand Biodiversity Action Plan, 2016-2020,” 2016

[26] https://www.doc.govt.nz/documents/science-and-technical/sap244.pdf

[27] Auckland Council, “Indigenous Biodiversity Strategy,” 2012

[28] The Auckland Plan, “Outcome: Environment and cultural heritage,” https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/auckland-plan/environment-cultural-heritage/Pages/default.aspx (accessed May 24, 2018).

[29] Forest and Birds, “North-West Wildlnk,” http://www.forestandbird.org.nz/what-we-do/projects/northwest-wildlink (accessed May 24, 2018).

[30] Auckland Council, “Weiti Wild-Link,” https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-projects/projects-north-auckland/Pages/weiti-wild-link.aspx (accessed May 24, 2018).

[31] https://www.doc.govt.nz/Documents/getting-involved/landowners/nature-heritage-fund/nhf-akld-protection-strat.pdf

[32] Auckland Council, “The Health of Auckland’s Natural Environment in 2015,” 2015

[33] Auckland Council, “Auckland Council Weed Management Policy for parks and open spaces,” 2013

[34] Auckland Council, “How we control pests,” https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/environment/plants-animals/pests-weeds/Pages/how-we-control-pests.aspx (accessed May 24, 2018).

[35] Wendy A. Ruscoe, et al., “Effects of Spatially Extensive Control of Invasive Rats on Abundance of Native Invertebrates in Mainland New Zealand Forests,” Conservation Biology 27, no. 1 (2012)

[36] Jay Ruffell & Raphael K. Didham, “Conserving biodiversity in New Zealand’s lowland landscapes: does forest cover or pest control have a greater effect on native birds?,” New Zealand Journal of Ecology 41, no. 1 (2017): 23-33.

[37] https://www.doc.govt.nz/Documents/getting-involved/landowners/nature-heritage-fund/nhf-akld-protection-strat.pdf

[38] Auckland Council, “Parks and Beaches,” https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/parks-recreation/Pages/find-park-beach.aspx (accessed June 13, 2018)

[39] NZTCV, “Motuihe Island,” http://www.conservationvolunteers.org.nz/projects/view/motuihe_island (accessed June 13, 2018)

[40] Auckland Council, “Million Trees,” https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/mayor-of-auckland/mayor-priorities/protecting-our-environment/Pages/million-trees.aspx (accessed June 13, 2018)

[41] Auckland Council, “Auckland Growing Greener,” 2016

[42] Department of Conservation, “Treasure Islands,” https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/auckland/hauraki-gulf-marine-park/know-before-you-go/treasure-islands/ (accessed May 24, 2018).

[43] Auckland Council, “Plant for your local ecosystem,” https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/environment/plants-animals/plant-for-your-ecosystem/Pages/default.aspx (accessed May 24, 2018).