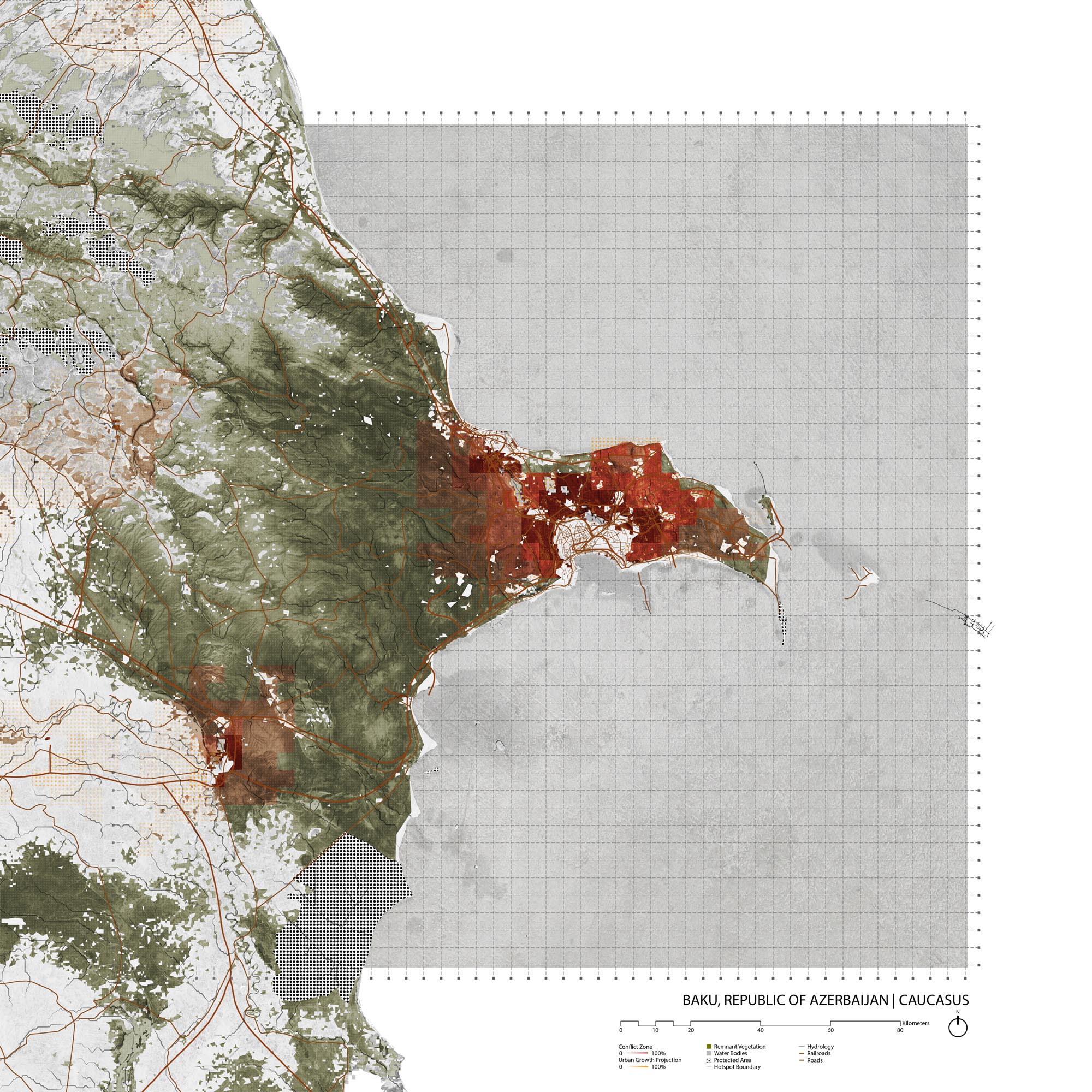

Baku, Azerbaijan

- Global Location plan: 40.41oN, 49.8oE

- Hotspot: Caucasus

- Population 2015: 2,374, 000

- Projected population 2030: 2,971, 000

- Mascot Species: Karabakh horse (Equus ferus caballus), peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), Persian gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa)

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Bufotes variabilis

- Hyla arborea

- Pelophylax ridibundus

- Triturus karelinii

- Hyla savignyi

- Pelobates syriacus

- Rana macrocnemis

Mammals

- Microtus daghestanicus

- Meriones libycus

- Meriones vinogradovi

- Meriones persicus

- Mesocricetus brandti

- Microtus nasarovi

- Microtus arvalis

- Tadarida teniotis

- Barbastella leucomelas

- Myotis schaubi

- Nyctalus leisleri

- Rhinolophus blasii

- Rhinolophus ferrumequinum

- Rhinolophus euryale

- Glis glis

- Ursus arctos

- Rupicapra rupicapra

- Lepus europaeus

- Talpa levantis

- Pusa caspica

- Ursus arctos

- Ursus arctos

- Capreolus capreolus

- Felis silvestris

- Pipistrellus pygmaeus

- Barbastella barbastellus

- Myotis aurascens

- Plecotus macrobullaris

- Apodemus witherbyi

- Erinaceus roumanicus

- Crocidura caspica

- Myotis emarginatus

- Pipistrellus nathusii

- Allactaga williamsi

- Sus scrofa

- Rattus rattus

- Eptesicus bottae

- Apodemus hyrcanicus

- Myotis nipalensis

- Panthera pardus

- Erinaceus concolor

- Nyctalus noctula

- Mus musculus

- Suncus etruscus

- Crocidura suaveolens

- Chionomys gud

- Felis chaus

- Pipistrellus kuhlii

- Meriones tristrami

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Mus macedonicus

- Allactaga major

- Lutra lutra

- Hypsugo savii

- Meles meles

- Myotis blythii

- Crocidura serezkyensis

- Hystrix indica

- Allactaga elater

- Apodemus uralensis

- Cervus elaphus

- Vulpes vulpes

- Vormela peregusna

- Rhinolophus hipposideros

- Hemiechinus auritus

- Nyctereutes procyonoides

- Micromys minutus

- Vespertilio murinus

- Crocidura leucodon

- Neomys teres

- Martes foina

- Arvicola amphibius

- Dryomys nitedula

- Ellobius lutescens

- Gazella subgutturosa

- Hyaena hyaena

- Martes martes

- Ovis orientalis

- Capra aegagrus

- Capra aegagrus

- Microtus socialis

- Canis lupus

- Apodemus ponticus

- Capra cylindricornis

- Cricetulus migratorius

- Mustela nivalis

- Pipistrellus pipistrellus

- Myotis nattereri

- Lynx lynx

- Eptesicus serotinus

- Plecotus auritus

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

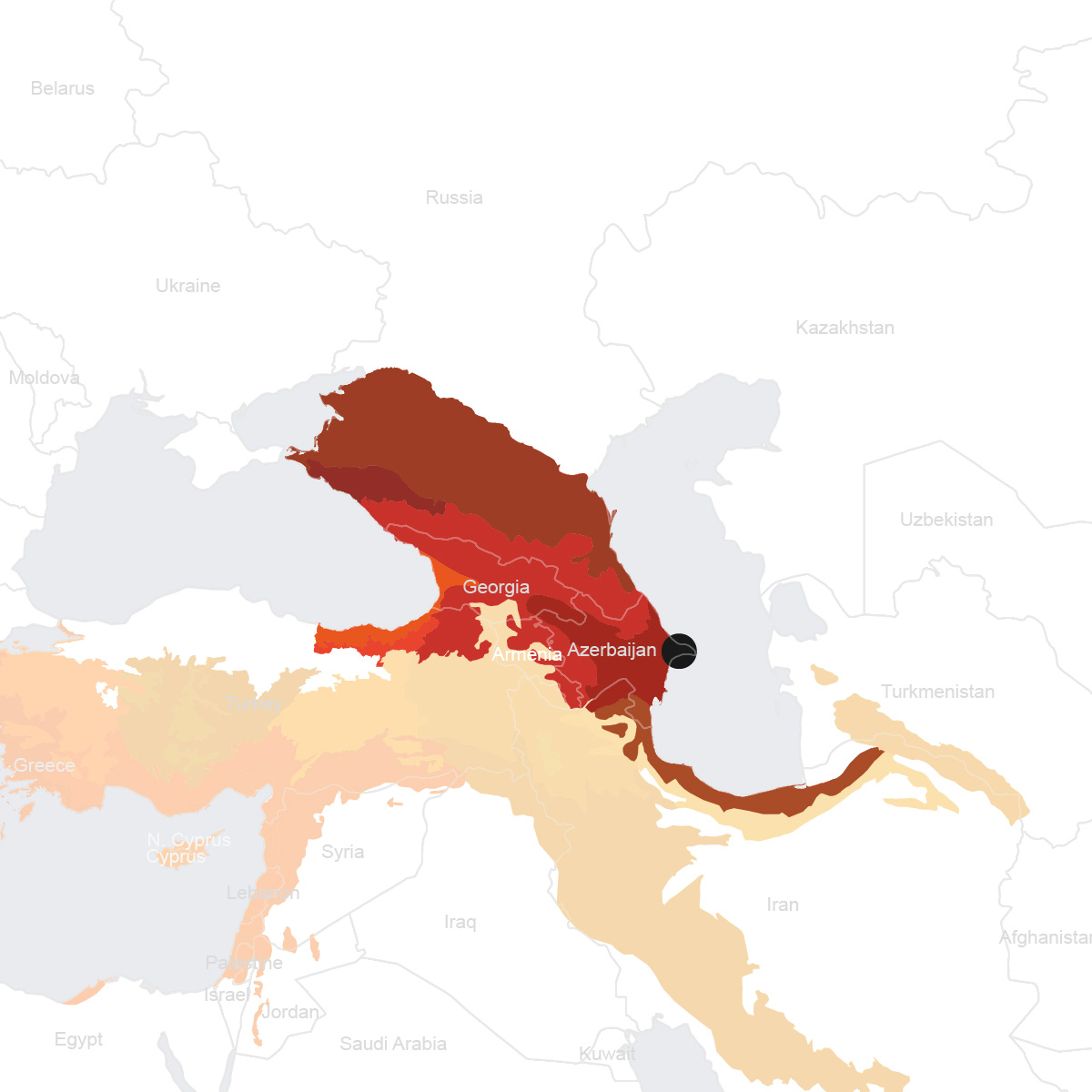

The Caucasus Hotspot spans across Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Containing deserts, savannas, swamp forests, and arid woodlands, the area is not only biologically important but also a globally significant center of cultural diversity. Caucasus has been inhabited by humans for millennia, and today still nurtures a multitude of ethnic groups, languages, and religions. [1]

Species statistics [2]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~6,400 |

>25% |

- 17 endemic genera - rhododendrons Rhododendron caucasicum , R. ungernii , and R. smirnowii - concentration of wild crop relatives such as wheat, rye, barley, and walnuts, apricots, apples |

|

Birds |

DD |

DD |

- significant number of breeding raptors - two major migration routes each summer and autumn, along the east coast of the Black Sea and the west coast of the Caspian Sea |

|

Mammals |

~130 |

~20 |

- Endangered Caspian seal ( Pusa caspica ) |

|

Reptiles |

~90 |

~20 |

|

|

Amphibians |

DD |

DD |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

>125 |

~12 |

- living fossil lampreys - Critically Endangered Beluga sturgeon ( Huso huso ), the largest freshwater fish and the source of high-value caviar |

Nearly half of the Caucasus Biodiversity Hotspot has been transformed by human activities. About 27 percent of the rest of the land remain as natural habitats, but only about 12 percent is considered pristine, mostly in the higher mountain regions. Only two to three percent of riparian forests are left. Major threats include illegal logging, fuelwood harvesting, and the timber trade. Overgrazing is another great issue, as a third of all pasturelands are subject to erosion. Following the opening of borders in the former Soviet countries, poaching and illegal wildlife trade have grown tremendously. Even legal game species (e.g. ungulates) suffer overhunting due to inappropriate quota setting. Other impact sources contain infrastructure development, oil extraction, agriculture, private use of chemicals, and pollution from settlement and factory runoffs.

[3]

CEPF invested 9.5 million US dollars from 2003 to 2013 in the Caucasus hotspot, which contributed to system-level planning, management and new establishment of protected areas, and development of sustainable mechanisms.

[4]

Azerbaijan Shrub Desert and Steppe

Seventy percent of the ecoregion is within Azerbaijan, with the rest in southeast Georgia and northwest Iran. The climate is characterized by aridity, long hot summers, and mild short winters. It is the driest region in the Caucasus, with an average annual precipitation of 300-400 mm. There are three primary zonal landscape types – desert/semi-desert, arid open woodland, and steppe – plus intra-zonal floodplain riparian forests along rivers and wetlands. An interesting steppe type is the relatively tall (~1m) phorb grassland, similar to the North American prairies and dominated by yellow bluestems ( Bothriochloa ischaemum ). [5]

The ecoregion contains about 4,000 plant and 15,000 animal species, with the reptile diversity most notable. The Vulnerable goitered gazelle ( Gazella subgutturosa ) [6] is one iconic species. Some characteristic avifauna are griffon vulture ( Gyps fulvus ) and white-tailed eagle ( Haliaeetus albicilla ). The region’s shoreline and wetlands boost particular importance during migration and wintering periods; southern European waterfowls and other species such as bustards take refuge here in the winter. [7]

By 1998, an estimated 1.2 million hectares in Azerbaijan are affected by steep salinity (due to excessive and long-term use of agricultural chemicals), and another 3 million hectares are damaged by overgrazing and logging. Only 5 to 7 percent of the original floodplain forests and pistachio-juniper woodlands remain. Overhunting for sport is another serious issue. [8] At present, the ecoregion is 6 percent conserved (within 20 protected areas), but only 2.18 percent terrestrially connected. [9]

Environmental History

Around 15,000 years ago as the last ice age was ending, the landscape around Baku was both wetter and greener than today. [10] Nomadic hunters flourish in this savanna and left well-preserved rock paintings. By the end of the first century BCE, Baku was a seaport town in the farthest reaches of the Roman Empire. [11] The presence of oil reserves in the Caspian Sea near Baku was in the 5th century, when Pricsus Panites wrote about “flames gushing from the sea.” [12] Baku rose to regional prominence starting in the 10th century when it became one of the most important cities in Shirvan. The Shirvanshahs, who ruled the area, later had to move the capital to Baku after an earthquake in the previous capital. In medieval times, rising seas from the Caspian Seas sometimes flooded the area. [13]

Although it’s unclear exactly when the oil industry in Baku started, by 1264 Baku was and still continues to be a trading center for oil. [14] In 1847, the first mechanical oil rig was built in Bibi-Heybat. [15] Afterwards, the oil industry continued to flourish and the population increased dramatically. By 1913, Baku’s heavy extraction was producing almost 95% of all Russian oil and 55% of the total global oil production. [16] This economic growth, from both oil and later natural gas, continued as Azerbaijan became a part of the USSR. Although much of the easily extractable oil is gone, the oil industry still continues and is supplemented by industrial manufacturing. [17] Following the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Baku is transforming itself into a global city with the fastest growth in the region. [18] Elites and the government, wanting to attract foreign wealth, drive most of the development, in opposition to the planned, centralized development during the Soviet Era. Housing shortages and high prices contribute to informal settlements, where around 50% of Baku’s population lives. [19]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Much of the environmental damage to the region has come oil extraction near Baku. Air pollution comes from oil, wells, refineries, and factories, while off and onshore oil pollution kills vegetation and contaminates marine life and drinking water. [20] Agricultural practices have further damaged the landscape. Excessive use of fertilizer, pesticides, and herbicides spreads toxic residue and disturbs the natural ecosystem. [21]

Inefficient and destructive land use also contributes strongly to the ecoregion’s environmental degradation. 27% of the original habitat remains, while only 12% remains intact and 5% of Azerbaijan’s land is protected. [22] Intact land is mainly in the mountainous regions while floodplain forests and other woodlands are most affected. Deforestation has risen since the fall of the Soviet Union; as power supply has either shrunken or disappearance, people turn to firewood to fulfill their power needs. [23] The Caspian Sea in particularly is susceptible to environmental and biodiversity threats. Urban, commercial, and industrial development have changed the coastal landscape. In addition to oil extraction, Baku’s environment is harmed by coastal development, commercial fishing, and water level rise. [24]

The ecoregion also includes around 60 species of animals and 140 species vascular plants that are considered endangered. [25] .Overhunting contributes to population decline.

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Baku’s growth is both supported by formal and informal development. Unexpected population growth, internally displaced people moving to the area for work, corrupt and ineffective construction bureaucracy, lack of punishment, and lack of institutional coordination have all greatly contributed to the presence of informal settlements. [26] Baku’s informal settlements often occur when developers construct buildings without full state approval or or when developments have legally obtained documents that aren’t recognized by other governmental institutions. [27] Another issue with Baku’s informal settlement is that they are often built near infrastructural utilities, putting both the residents and access to these utilities at risk. [28] Moreover, the formal growth that does happen is similarly uncoordinated. Both the government and the private sector lead Baku’s rapid development towards tourists and the rich rather than Baku’s own residents, making Baku an increasingly expensive city to both visit and live. [29]

Governance

Baku as a city is under direct control of the Azerbaijani national government. The president of Azerbaijan appoints the mayor (EP) and the heads of Baku’s twelve administrative districts. [30] Almost no institutional policy or structure exists to assure coordination in decision making, which each district making decisions usually in isolation. Also, no clear separation of powers between the EP and district heads exists. There are 52 municipalities, or democratically elected units of local self-governance, in Baku and the surrounding area. [31] The municipalities are designed to handle local issues through programs, but generally don’t have enough financial or political power to become a true third-tier of government after the EP and district heads.

There is little press freedom, information dissemination, and public participation regarding state affairs. [32]

City Policy/Planning

Development Plan

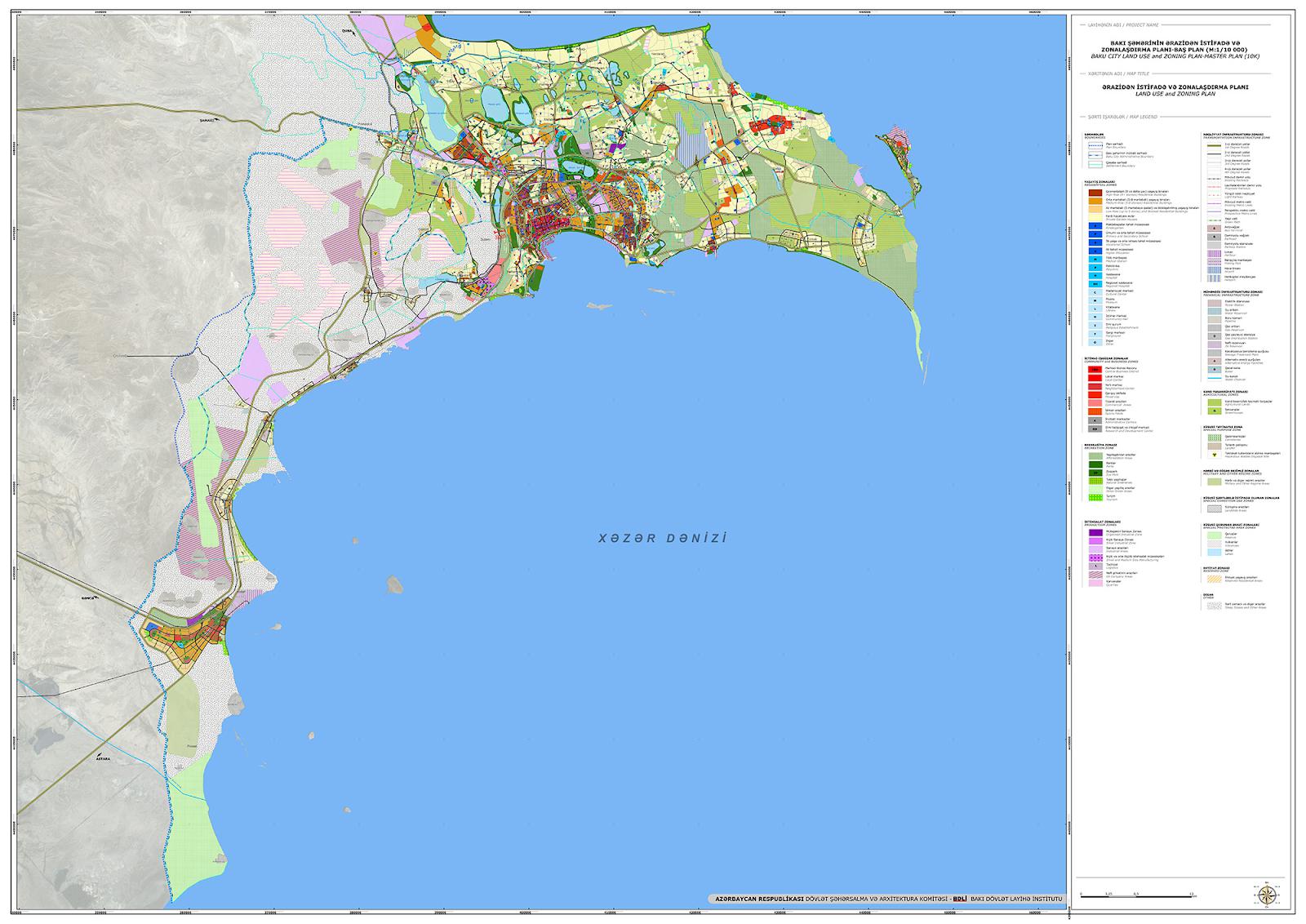

The State Committee for City Building and Architecture, established in 2006, in the Azerbaijani cabinet is in charge of regulating urban and architectural development in Azerbaijan and, by extension, Baku. [33] The exact structure of this committee is unable to be found. In 1954, the first general plan for the development and planning of the Absheron Peninsula and Baku region was finished. The last plan was finished in 1985 and covered a 20 year period, meaning that as of 2006 there is no master plan currently being implemented for the Baku region. [34]

Baku State Design Institute (BDLI) has commenced the project “Greater Baku Regional Development Plan” under the auspices of the Azerbaijani government and the World Bank. [35] The Greater Baku Regional Development Plan is focuses on regional development with attention to economic growth, transportation, housing, social issues, landscaping, and historic preservation. [36] As of 2018, the State Committee for City Building and Architecture announced that the master plan of Baku was in still the works and coordinating with foreign companies. [37]

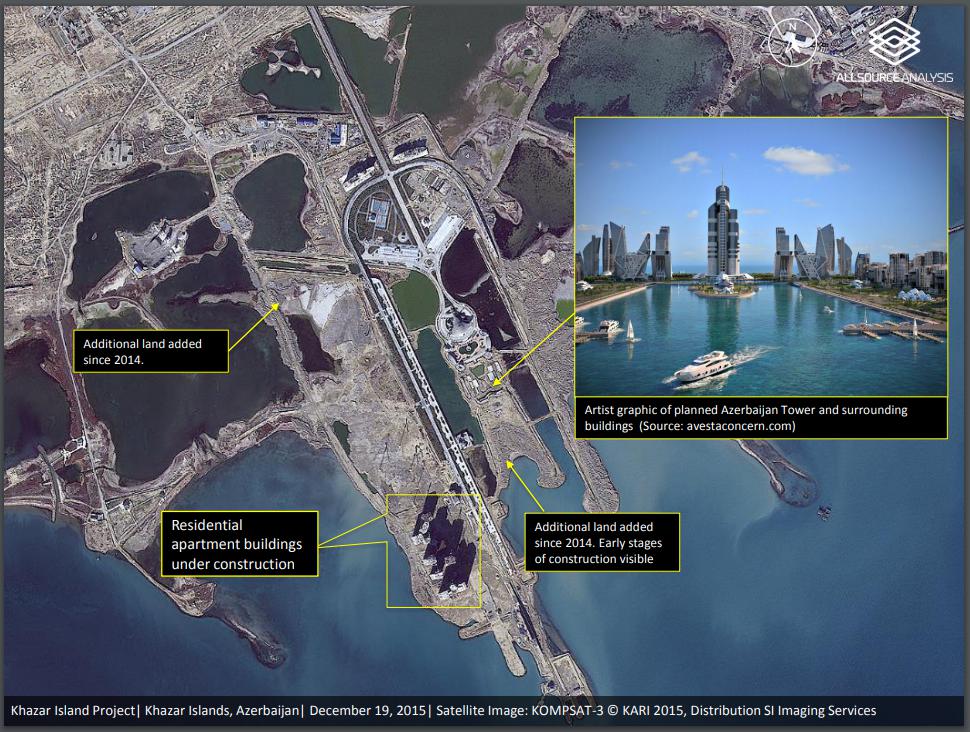

Baku’s urban planning is generally at the hands of elite’s interest; the current real estate boom allows a diversification of Baku’s economy by moving away from oil dependence. [38] The structure of state bureaucracy also means that the influence of money and patronage directs licenses and permits towards elites’ own projects rather than those that are more likely to benefit Baku as a whole. [39] One of the main development plans in Baku’s construction boom is Khazar Islands, a man-made of over 40 islands designed to hold 1 million people, cultural centers, and the world’s tallest building, the Azerbaijan Tower. [40] The site is planned to be completed in 2025, but currently the project remains at a standstill. [41] Although the exact story couldn’t be found, it appears that funding for the project has been lost and plans for the Azerbaijan Tower were scrapped. [42]

Zoning

There is no active zoning plan for Baku. The previous master plans did detail zoning policy, but currently no master plan exists. [43] In conjunction with the Greater Baku Regional Development Plan, BDLI is also working on the “Baku City Land Use and Zoning Plan.” [44] The zoning plan includes different levels of industrial zones and creating different subcenters to decentralize activity in Baku. The project also stipulates environmental protection through planting, but the details are unclear.

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Azerbaijan is a member of the CBD and released its most recent plan in 2016. Compared with the previous action plan (adopted in 2006), numerous protected areas have been either established or expanded. The current revision is the National Strategy of the Republic of Azerbaijan on Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity for 2017-2020 (The National Strategy). The priority objectives include increasing awareness, strengthening institutional capacity, and restoring and protecting biodiversity. The plan does not list urbanization as a specific threat or concern. [45]

National

The Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources is in charge of environmental policies at a national level. [46] Law of the Republic of Azerbaijan on Animals regulates the ways that wildlife can be used and supports wildlife conservation and protection. [47] Other laws cover ecological safety, environmental protection, and protected areas. [48] No biodiversity plan is apparent on the government’s website.

Protected Areas

Absheron National Park is located east of Baku on the Absheron peninsula. No other protected areas are near Baku.

Public Awareness

Azerbaijan’s poor record of press freedom and citizen participation makes it hard to accurately assess public awareness regarding issues of biodiversity issues. From what limited publications are available in English, it seems that the public awareness is most likely stunted by a sense of futility about government’s responsiveness to ordinary citizens’ needs. This is underscored by a general lack of transparency as evident from the fact that government and urban authorities rarely inform the public about construction projects before they commence. [49] There is little information on the government’s website about biodiversity, other than an oddly detailed page on biodiversity degradation in what seems to be the land controlled by the Republic of Artsakh. [50] The spread of information about biodiversity does not seem to exist when it doesn’t support current state policy and business interests.

[1] CEPF. “Caucasus.” Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/caucasus .

[2] CEPF. “Caucasus - Species.” Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/caucasus/species.

[3] CEPF. “Caucasus - Threats.” Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/caucasus/threats.

[4] CEPF. “Caucasus.” Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/caucasus.

[5] WWF. “Southwestern Asia: Azerbaijan, into Georgia and Iran | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1305.

[6] “Goitered Gazelle.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[7] WWF. “Southwestern Asia: Azerbaijan, into Georgia and Iran | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1305.

[8] WWF. “Southwestern Asia: Azerbaijan, into Georgia and Iran | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1305.

[9] “Azerbaijan Shrub Desert and Steppe.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/81305.

[10] National Geographic, “Rock Art Reveals Prehistoric ‘Serengeti’ in the Caucasus,” https://www.nationalgeographic.org/projects/out-of-eden-walk/articles/2016-03-rock-art-reveals-prehistoric-serengeti-in-the-caucasus/ (accessed August 2, 2018)

[11] Baku Salam, “Baku History,” http://salambaku.travel/en/baku/history (accessed August 2, 2018)

[12] Trip to Azerbaijan, “Capital,” http://triptoazerbaijan.com/en/baku/ (accessed August 2, 2018)

[13] A. Naderi Beni, et al., “Caspian sea-level changes during the last millennium,” Climate of the Past 9, issue no. 4 (2013):1645-1665.

[14] Energy Global News, “MARCO POLO SAW OIL IN BAKU IN 1264,” http://www.energyglobalnews.com/marco-polo-saw-oil-baku-1624/ (accessed August 2, 2018)

[15] Azerbaijan, “HISTORY OF DEVELOPMENT OF OIL INDUSTRY,” http://www.azerbaijan.az/portal/Economy/OilStrategy/oilStrategy_02_e.html (accessed August 2, 2018)

[16] Anar Valiyev, "Baku" Cities 31, (2013): 625-640

[17] Britannica, “Baku,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Baku (accessed August 2, 2018)

[18] Anar Valiyev, "Baku" Cities 31, (2013): 625-640

[19] ibid.

[20] Azerbaijan International,, “Major Environmental Issues in Azerbaijan,” https://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/23_folder/23_articles/23_overview.html (accessed August 3, 2018)

[21] ibid.

[22] Asian Development Bank, “Azerbaijan Country Environmental Analysis,” https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/32178/aze-cea.pdf (accessed August 3, 2018)

[23] ibid.

[24] ibid.

[25] WWF, “Southwestern Asia: Azerbaijan, into Georgia and Iran,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1305 (accessed July 31, 2018)

[26] Anar Valiyev, "Baku" Cities 31, (2013): 625-640

[27] United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, “Azerbaijan,” https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/hlm/documents/Publications/cp.azerbaijan.e.pdf (accessed August 4, 2018): 2-22

[28] Anar Valiyev, "Baku" Cities 31, (2013): 625-640

[29] ibid.

[30] ibid.

[31] International Foundation for Election Systems, “Municipalities in Azerbaijan,” https://www.ifes.org/sites/default/files/r01522.pdf (accessed August 4, 2018)

[32] Anar Valiyev, "Baku" Cities 31, (2013): 625-640

[33] Azerbaijan, “STATE TOWN BUILDING AND ARCHITECTURE COMMITTEE OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN,” http://www.azerbaijan.az/portal/StatePower/Committee/committeeConcern_19_e.html? (accessed August 4, 2018)

[34] Anar Valiyev, "Baku" Cities 31, (2013): 625-640

[35] Today, “Spatial Planning for a greater Baku,” http://today.az/news/politics/164641.html (accessed August 6, 2018)

[36] Baku State Design Institute, “PRESENTATION OF THE "GREATER BAKU REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN" PROJECT,” http://bdli.az/web/?p=620 (accessed August 6, 2018)

[37] Trend, “Boston Consulting Group to help Azerbaijan prepare Baku general plan,” https://en.trend.az/business/economy/2930235.html (accessed August 4, 2018)

[38] Farid Guliyev, “Urban Planning in Baku: Who is Involved and How It Works,” Caucasus Analytical Digest 11, (2018)

[39] ibid

[40] Design Build Network, “Khazar Islands, Absheron Peninsula,” https://www.designbuild-network.com/projects/khazar-islands-azerbaijan/ (accessed August 4, 2018)

[41] Tim Franco, “Khazar Islands, a failed urban dream?,” http://www.timfranco.com/china/photographer/professional/shanghai/blog/2016/12/12/khazar-islands-a-failed-urban-dream- (accessed August 4, 2018)

[42] Reconnaissance Europe, “Azerbaijan,” https://reconnaissance-europe.com/2018/01/03/azerbaijan/ (accessed August 6, 2018)

[43] Anar Valiyev, "Baku" Cities 31, (2013): 625-640

[44] Today, “Spatial Planning for a greater Baku,” http://today.az/news/politics/164641.html (accessed August 6, 2018)

[45] CBD, “CBD Strategy and Action Plan - Azerbaijan (English version),” https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/az/az-nbsap-v2-en.pdf (accessed August 6, 2018).

[46] Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan Republic, “Ministry,” http://eco.gov.az/en/4-ministry (accessed August 6, 2018)

[47] The Law, “About the Animals,” http://e-qanun.az/framework/3850 (accessed August 6, 2018)

[48] Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan Republic, “Laws,” http://eco.gov.az/en/19-laws (accessed August 6, 2018)

[49] Anar Valiyev, "Baku" Cities 31, (2013): 625-640

[50] Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan Republic, “The ecological situation in occupied territories,” http://eco.gov.az/en/111-the-ecological-situation-in-occupied-territories (accessed August 6, 2018)