Bogotá, Colombia

- Global Location plan: 4.71oN, 74.07oW[1]

- Hotspot: Tropical Andes

- Ecoregion: Magdalena Valley Montane Forests (needs an additional + 4,376 km2 protected areas)

- Population 2016: 9,968,000

- Projected population 2030: 11,966,000

- Mascot Species: Andean Condors, Andean guans, Endangered Spectacled Bears, and Golden Eagles[2]

- Primary Crops: Flowers, Bananas (also in forestry plantations), Cereals and cereal products, Maize, Onions+Shallots Green, Potatoes, Roots tubers; Livestock: Cattle, Pigs, Poultry, Sheep[3]

- Primary Industry: Historic: Textiles, Pharmaceuticals, Food Processing

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Dendropsophus minutus

- Scinax rostratus

- Pristimantis acutirostris

- Hyloscirtus antioquia

- Pristimantis parectatus

- Pristimantis factiosus

- Caecilia thompsoni

- Dendropsophus stingi

- Dendropsophus columbianus

- Boana crepitans

- Hyloscirtus larinopygion

- Scinax x-signatus

- Centrolene hybrida

- Centrolene medemi

- Hyalinobatrachium valerioi

- Hyloscirtus phyllognathus

- Pristimantis lichenoides

- Pristimantis mnionaetes

- Rhinella marina

- Pristimantis affinis

- Pristimantis bicolor

- Pristimantis boulengeri

- Dendropsophus molitor

- Pristimantis maculosus

- Leptodactylus knudseni

- Dendropsophus microcephalus

- Bolitoglossa altamazonica

- Pristimantis simoteriscus

- Pristimantis renjiforum

- Rhinella granulosa

- Nymphargus griffithsi

- Atelopus lozanoi

- Atelopus muisca

- Atelopus quimbaya

- Atelopus simulatus

- Rhaebo guttatus

- Rhaebo haematiticus

- Rhinella margaritifera

- Amazophrynella minuta

- Centrolene antioquiense

- Centrolene geckoideum

- Nymphargus chami

- Rulyrana susatamai

- Allobates femoralis

- Hyloxalus abditaurantius

- Hyloxalus ramosi

- Dendrobates truncatus

- Andinobates virolinensis

- Cryptobatrachus fuhrmanni

- Boana boans

- Hyloscirtus denticulentus

- Dendropsophus garagoensis

- Hyloscirtus palmeri

- Hyloscirtus piceigularis

- Boana punctata

- Scarthyla vigilans

- Osteocephalus buckleyi

- Scinax blairi

- Scinax ruber

- Scinax wandae

- Smilisca phaeota

- Smilisca sila

- Sphaenorhynchus lacteus

- Pristimantis bogotensis

- Pristimantis dorsopictus

- Pristimantis elegans

- Pristimantis frater

- Pristimantis gracilis

- Strabomantis ingeri

- Niceforonia latens

- Pristimantis lemur

- Niceforonia mantipus

- Strabomantis necopinus

- Pristimantis orpacobates

- Pristimantis penelopus

- Craugastor raniformis

- Pristimantis susaguae

- Pristimantis uisae

- Pristimantis veletis

- Pristimantis viejas

- Pristimantis w-nigrum

- Leptodactylus fragilis

- Leptodactylus fuscus

- Leptodactylus mystaceus

- Niceforonia columbiana

- Engystomops pustulosus

- Leucostethus fraterdanieli

- Ctenophryne geayi

- Elachistocleis ovalis

- Pipa pipa

- Lithobates palmipes

- Caecilia corpulenta

- Caecilia orientalis

- Siphonops annulatus

- Typhlonectes natans

- Osornophryne percrassa

- Gastrotheca bufona

- Gastrotheca nicefori

- Pristimantis brevifrons

- Hyalinobatrachium esmeralda

- Pseudis paradoxa

- Andinobates bombetes

- Hyalinobatrachium colymbiphyllum

- Pristimantis medemi

- Pristimantis palmeri

- Dendropsophus luddeckei

- Bolitoglossa lozanoi

- Rulyrana adiazeta

- Colostethus mertensi

- Pristimantis dorado

- Andinobates opisthomelas

- Niceforonia adenobrachia

- Lithobates catesbeianus

- Potomotyphlus kaupii

- Pristimantis helvolus

- Hyloxalus lehmanni

- Phyllomedusa venusta

- Pithecopus hypochondrialis

- Dendropsophus brevifrons

- Dendropsophus ebraccatus

- Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni

- Pristimantis maculosus

- Pristimantis maculosus

- Pristimantis buckleyi

- Caecilia degenerata

- Espadarana prosoblepon

- Ameerega hahneli

- Nymphargus spilotus

- Dendropsophus mathiassoni

- Boana pugnax

- Trachycephalus typhonius

- Pristimantis erythropleura

- Leptodactylus bolivianus

- Pristimantis suetus

- Pristimantis fetosus

- Pristimantis scopaeus

- Hyalinobatrachium munozorum

- Atelopus farci

- Atelopus guitarraensis

- Atelopus minutulus

- Atelopus pedimarmoratus

- Atelopus subornatus

- Rhinella acutirostris

- Rhaebo glaberrimus

- Rhaebo haematiticus

- Rhinella sternosignata

- Rhinella ruizi

- Espadarana andina

- Centrolene buckleyi

- Nymphargus grandisonae

- Centrolene notostictum

- Centrolene quindianum

- Centrolene robledoi

- Centrolene robledoi

- Centrolene daidaleum

- Rulyrana flavopunctata

- Nymphargus garciae

- Nymphargus posadae

- Sachatamia punctulata

- Cochranella resplendens

- Nymphargus rosada

- Centrolene savagei

- Hyloxalus edwardsi

- Hyloxalus ruizi

- Hyloxalus subpunctatus

- Hyloxalus vergeli

- Gastrotheca dendronastes

- Hemiphractus johnsoni

- Hyloscirtus bogotensis

- Boana lanciformis

- Dendropsophus subocularis

- Osteocephalus taurinus

- Adenomera hylaedactyla

- Pristimantis acatallelus

- Pristimantis achatinus

- Pristimantis alalocophus

- Niceforonia babax

- Pristimantis carranguerorum

- Pristimantis fallax

- Hyloxalus bocagei

- Lithobates vaillanti

- Strabomantis ingeri

- Craugastor longirostris

- Pristimantis lynchi

- Pristimantis nervicus

- Pristimantis permixtus

- Pristimantis permixtus

- Pristimantis piceus

- Pristimantis renjiforum

- Pristimantis simoteriscus

- Pristimantis simoterus

- Pristimantis torrenticola

- Pristimantis tribulosus

- Pristimantis uranobates

- Leptodactylus colombiensis

- Lithodytes lineatus

- Craugastor metriosistus

- Physalaemus fischeri

- Pleurodema brachyops

- Pseudopaludicola boliviana

- Pseudopaludicola llanera

- Leptodactylus discodactylus

- Atelopus mandingues

- Atelopus minutulus

- Elachistocleis panamensis

- Ctenophryne aterrima

- Elachistocleis pearsei

- Leucostethus brachistriatus

- Dendropsophus padreluna

- Pristimantis actinolaimus

- Pristimantis gaigei

- Pristimantis affinis

- Bolitoglossa capitana

- Bolitoglossa capitana

- Bolitoglossa ramosi

- Bolitoglossa vallecula

- Microcaecilia albiceps

- Microcaecilia nicefori

- Microcaecilia pricei

- Pristimantis taeniatus

- Pristimantis thectopternus

- Andinobates dorisswansonae

- Colostethus ucumari

- Andinobates tolimensis

- Allobates niputidea

- Diasporus anthrax

- Andinobates daleswansoni

- Agalychnis terranova

- Pristimantis stictus

- Pristimantis racemus

- Rheobates palmatus

- Rheobates pseudopalmatus

- Bolitoglossa pandi

- Oscaecilia polyzona

- Hyloxalus breviquartus

- Allobates cepedai

- Allobates juanii

- Pristimantis paisa

- Allobates ranoides

- Bolitoglossa adspersa

- Caecilia guntheri

- Colostethus thorntoni

- Caecilia pachynema

- Caecilia subdermalis

Mammals

- Coendou vestitus

- Chrotopterus auritus

- Vampyressa melissa

- Sylvilagus floridanus

- Microsciurus alfari

- Phylloderma stenops

- Marmosa lepida

- Microryzomys altissimus

- Microryzomys minutus

- Tadarida brasiliensis

- Aotus zonalis

- Marmosa demerarae

- Myrmecophaga tridactyla

- Neusticomys monticolus

- Pteronotus davyi

- Pteronotus gymnonotus

- Nyctinomops laticaudatus

- Olallamys albicauda

- Oligoryzomys griseolus

- Nephelomys albigularis

- Transandinomys talamancae

- Peropteryx pallidoptera

- Panthera onca

- Vampyressa thyone

- Sciurus granatensis

- Platyrrhinus infuscus

- Platyrrhinus vittatus

- Vampyriscus nymphaea

- Proechimys chrysaeolus

- Proechimys chrysaeolus

- Proechimys oconnelli

- Molossus sinaloae

- Diaemus youngi

- Oecomys bicolor

- Melanomys caliginosus

- Rhipidomys fulviventer

- Dasyprocta fuliginosa

- Cynomops paranus

- Lagothrix lugens

- Ateles hybridus

- Marmosa regina

- Tonatia saurophila

- Saimiri sciureus

- Galictis vittata

- Molossops neglectus

- Odocoileus virginianus

- Sapajus macrocephalus

- Platyrrhinus lineatus

- Phyllostomus discolor

- Rhogeessa minutilla

- Tayassu pecari

- Rhogeessa io

- Vampyrodes caraccioli

- Vampyrodes major

- Sturnira ludovici

- Platyrrhinus helleri

- Platyrrhinus dorsalis

- Thyroptera tricolor

- Myoprocta pratti

- Tayassu pecari

- Centronycteris centralis

- Nyctinomops macrotis

- Eumops glaucinus

- Promops centralis

- Hydrochoerus isthmius

- Saccopteryx antioquensis

- Micronycteris microtis

- Heteromys australis

- Myotis keaysi

- Rhynchonycteris naso

- Lasiurus ega

- Mazama bricenii

- Molossus coibensis

- Alouatta juara

- Artibeus aequatorialis

- Choloepus hoffmanni

- Pudu mephistophiles

- Lophostoma silvicolum

- Cryptotis thomasi

- Sciurillus pusillus

- Leptonycteris curasoae

- Ichthyomys hydrobates

- Oecomys trinitatis

- Macrophyllum macrophyllum

- Potos flavus

- Sturnira magna

- Cavia aperea

- Mazama nemorivaga

- Lionycteris spurrelli

- Lagothrix lugens

- Pecari tajacu

- Lutreolina crassicaudata

- Nasua nasua

- Handleyomys intectus

- Mus musculus

- Vampyriscus bidens

- Saccopteryx bilineata

- Gracilinanus dryas

- Mormoops megalophylla

- Cabassous unicinctus

- Eptesicus chiriquinus

- Micronycteris hirsuta

- Chilomys instans

- Chiroderma trinitatum

- Diclidurus albus

- Saguinus leucopus

- Cerdocyon thous

- Glossophaga longirostris

- Coendou prehensilis

- Histiotus montanus

- Sciurus igniventris

- Eumops dabbenei

- Caenolestes fuliginosus

- Rhinophylla pumilio

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus

- Saccopteryx leptura

- Nectomys grandis

- Platyrrhinus umbratus

- Gardnerycteris crenulatum

- Cryptotis medellinia

- Chiroderma villosum

- Nectomys rattus

- Bradypus variegatus

- Dasypus novemcinctus

- Tamandua tetradactyla

- Dactylomys dactylinus

- Herpailurus yagouaroundi

- Thomasomys baeops

- Inia geoffrensis

- Thomasomys bombycinus

- Thomasomys niveipes

- Rhinophylla fischerae

- Glossophaga commissarisi

- Sigmodon hirsutus

- Puma concolor

- Uroderma magnirostrum

- Procyon cancrivorus

- Platyrrhinus albericoi

- Chibchanomys trichotis

- Monodelphis adusta

- Leopardus tigrinus

- Lasiurus cinereus

- Lasiurus egregius

- Dasypus kappleri

- Histiotus humboldti

- Sciurus spadiceus

- Eumops hansae

- Myotis oxyotus

- Thyroptera discifera

- Cormura brevirostris

- Eira barbara

- Lophostoma brasiliense

- Gracilinanus marica

- Glyphonycteris sylvestris

- Lophostoma carrikeri

- Tremarctos ornatus

- Tylomys mirae

- Anoura latidens

- Dinomys branickii

- Carollia castanea

- Neacomys tenuipes

- Dermanura glauca

- Cynomops greenhalli

- Priodontes maximus

- Thomasomys aureus

- Philander opossum

- Noctilio leporinus

- Cyclopes didactylus

- Micronycteris minuta

- Caluromys lanatus

- Anoura geoffroyi

- Oecomys concolor

- Bassaricyon neblina

- Bassaricyon neblina

- Bassaricyon alleni

- Sphaeronycteris toxophyllum

- Rhipidomys caucensis

- Rhipidomys latimanus

- Coendou rufescens

- Trinycteris nicefori

- Cebus albifrons

- Molossus rufus

- Rhipidomys couesi

- Marmosops fuscatus

- Molossus pretiosus

- Myotis nigricans

- Choeroniscus minor

- Zygodontomys brevicauda

- Saccopteryx canescens

- Sigmodon alstoni

- Sturnira aratathomasi

- Sturnira bidens

- Sturnira bogotensis

- Sturnira erythromos

- Aotus brumbacki

- Plecturocebus ornatus

- Ateles hybridus

- Metachirus nudicaudatus

- Molossus bondae

- Ateles fusciceps

- Philander mondolfii

- Didelphis pernigra

- Coendou pruinosus

- Mimon cozumelae

- Cryptotis brachyonyx

- Cryptotis colombiana

- Eumops trumbulli

- Coendou quichua

- Lonchophylla concava

- Platyrrhinus angustirostris

- Vampyrum spectrum

- Thomasomys princeps

- Anoura caudifer

- Anoura aequatoris

- Anoura peruana

- Lophostoma occidentalis

- Lonchophylla cadenai

- Lonchophylla orienticollina

- Lasiurus blossevillii

- Noctilio albiventris

- Aotus griseimembra

- Choeroniscus godmani

- Artibeus concolor

- Speothos venaticus

- Hylaeamys yunganus

- Nyctinomops aurispinosus

- Tamandua mexicana

- Tapirus terrestris

- Akodon affinis

- Necromys urichi

- Anotomys leander

- Eptesicus furinalis

- Cynomops abrasus

- Marmosa robinsoni

- Carollia brevicauda

- Carollia perspicillata

- Zygodontomys brunneus

- Holochilus sciureus

- Ametrida centurio

- Mazama americana

- Cuniculus paca

- Anoura cultrata

- Dermanura gnoma

- Enchisthenes hartii

- Artibeus lituratus

- Artibeus obscurus

- Didelphis marsupialis

- Marmosops caucae

- Chironectes minimus

- Dasyprocta punctata

- Thomasomys cinereiventer

- Choloepus didactylus

- Thomasomys contradictus

- Thomasomys laniger

- Thomasomys nicefori

- Oligoryzomys fulvescens

- Eumops auripendulus

- Dasypus sabanicola

- Desmodus rotundus

- Conepatus semistriatus

- Eptesicus andinus

- Eptesicus brasiliensis

- Eptesicus fuscus

- Furipterus horrens

- Nasuella olivacea

- Heteromys anomalus

- Leopardus pardalis

- Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris

- Lonchorhina aurita

- Lontra longicaudis

- Mesophylla macconnelli

- Cynomops planirostris

- Platyrrhinus brachycephalus

- Lichonycteris degener

- Pteronotus personatus

- Glyphonycteris daviesi

- Micronycteris schmidtorum

- Microsciurus mimulus

- Micronycteris megalotis

- Molossus molossus

- Myotis albescens

- Trachops cirrhosus

- Dermanura phaeotis

- Handleyomys alfaroi

- Euryoryzomys macconnelli

- Peropteryx kappleri

- Dermanura bogotensis

- Phyllostomus elongatus

- Phyllostomus hastatus

- Sciurus pucheranii

- Handleyomys fuscatus

- Cuniculus taczanowskii

- Neomicroxus bogotensis

- Necromys punctulatus

- Anoura luismanueli

- Aotus lemurinus

- Coendou bicolor

- Ateles belzebuth

- Artibeus amplus

- Cabassous centralis

- Peropteryx macrotis

- Uroderma bilobatum

- Dermanura rava

- Diphylla ecaudata

- Molossops temminckii

- Chiroderma salvini

- Glossophaga soricina

- Tapirus pinchaque

- Tapirus terrestris

- Mazama rufina

- Mimon bennettii

- Myotis riparius

- Centurio senex

- Reithrodontomys mexicanus

- Leopardus wiedii

- Lonchophylla robusta

- Lonchophylla thomasi

- Mustela frenata

Hotspot And Ecoregion Status

The Tropical Andes Biodiversity Hotspot is the most biologically diverse of all hotspots. It contains one-sixth of all plant species on the planet, and at least half are endemic. The hotspot also has more amphibian, bird, and mammal species than any other hotspot, and is only second in reptile diversity to Mesoamerica. [4] The region also contains incredible cultural diversity; more than 40 indigenous groups live here. Over 52 percent of the hotspot’s land area is owned by or reserved for indigenous peoples and communities. [5]

Species statistics [6]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~30,000 |

>50% |

|

|

Birds |

>1,700 |

~33% |

- Andean cock-of-the-rock ( Rupicola peruvianus ), Andean condor ( Vultur gryphus ) |

|

Mammals |

570 |

DD |

- Critically Endangered Peruvian yellow-tailed woolly monkey ( Oreonax flavicauda ) - rich in rodents and bats |

|

Amphibians |

~980 |

>670 |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

>375 |

DD |

|

The most degraded parts of the Tropical Andes Hotspot are regions surrounding Bogota --- the inter-Andean valleys. These regions have been hospitable to human settlement and therefore largely transformed for human use. Today, only 10% of the original vegetation remains. [7] The most significant threats to habitat in the hotspot include population pressure (e.g. urbanization) and migration, the continued expansion of transportation infrastructure (especially through previously mostly undisturbed ecosystems such as cloud forests), dams for hydroelectric production and irrigation, mining, firewood collection in remote areas, and illegal hunting for wildlife trade. [8]

CEPF invested US$8.13 million in the hotspot from 2001 to 2013, and continued with US$10 million in the current phase from 2015 to 2020. The organization now focuses on mainstreaming climate change resilience and strengthening capacities for indigenous people and Afro-descendents. [9]

Ecoregion Status

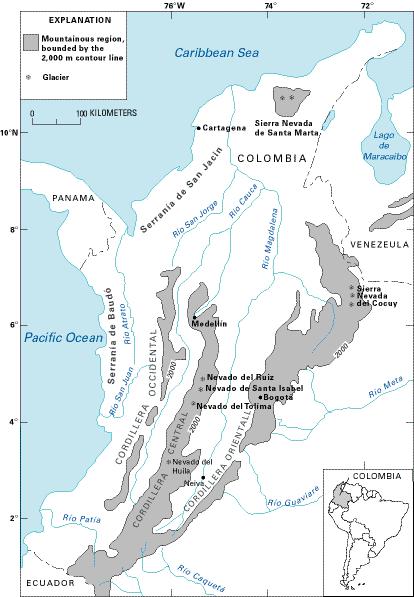

The Bogotá-Sabana Metropolitan region primarily coincides with the Magdalena Valley Montane Forests Ecoregion, with smaller areas in the Cordillera Oriental Montane Ecoregion and the Northern Andean Paramo.

Magdalena Valley Montane Forests

The Magdalena Valley Montane Forests ecoregion is on the inner slopes of the Eastern and Central Cordilleras, of the Northern Andes in Colombia. The climate is wet with rainy seasons, which fosters cloud forests at high elevations. Soils on the eastern and western slopes are mainly volcanic ashes and sedimentary respectively. Flora and fauna diversity are high. [10] Some species of special concern include Colombia’s national flower – Christmas orchid ( Cattleya trianae ), the Endangered [11] yellow-eared parrot ( Ognorhynchus icterotis ), and the Endangered [12] mountain tapir ( Tapirus pinchaque ). The latter two animals both have small roaming areas near Bogotá. Due to large-scale coffee farming and the fact that over 70 percent of the Colombian population resides in the region, few areas are still in good conditions. Conservation efforts are also scarcer at elevations below 2000 m. [13] At present, 15 percent of the ecoregion is protected, and 6.13 percent is considered connected. [14]

Cordillera Oriental Montane Forests

The Cordillera Oriental Montane Forests ecoregion spans the eastern slopes of the Andean Cordillera Oriental. The influence of the piedmont dry forests and the Llanos grasslands of the Orinoco basin distinguish this ecoregion from other montane forests of the Northern Andes. Biodiversity richness is outstanding on a global level. Current inventories suggest almost 900 bird species and 169 types of frogs, many of which are endemic. [15] Some noteworthy species include the Andean condor ( Vultur gryphus ) and the Vulnerable [16] spectacled bear ( Tremarctos ornatus ). In Colombia, 60 percent of the original vegetation in the ecoregion have been altered. Logging, agriculture (plus associated burning and use of herbicides), and extensive ranching activities have led to habitat loss and fragmentation. Hydroelectric projects and road infrastructure are also continuing threats. In Venezuela, livestock grazing and mining cause additional problems. [17] Currently, 27 percent of the ecoregion is under protection, and 14.06 percent has terrestrial connections. [18]

Northern Andean Paramo

Highland parks are critical to the protection of the unique, incredibly diverse, and threatened páramo ecosystem (also known as the high Andean Moorland), which only exists between 2800m and 4700m in the limized zone above the treeline but below the snowline. Because of the high elevations, páramos are effectively islands of plant endemism. It is estimated that more than 5,000 plant species grow in these here. [19] In fact, researchers have found that the páramo ecosystems have experienced the fastest rate of speciation among known fast-evolving hotspots. [20] This ecoregion is also valuable for its immense capacity for water capture and retention; because the vegetation acts as a giant sponge, these wetlands feed rivers and streams throughout the year, making them the most important water source in Colombia. When the vegetation is damaged, soils begin to erode, causing mudslides, sedimentation in creeks and rivers, and the deterioration of water quality. [21] Páramos are moreover very vulnerable to climate change. With rising temperatures, those species have no higher elevations to migrate to. [22] At present, 43 percent of the ecoregion is under protection, and 14.7 percent is considered connected. [23]

Environmental History

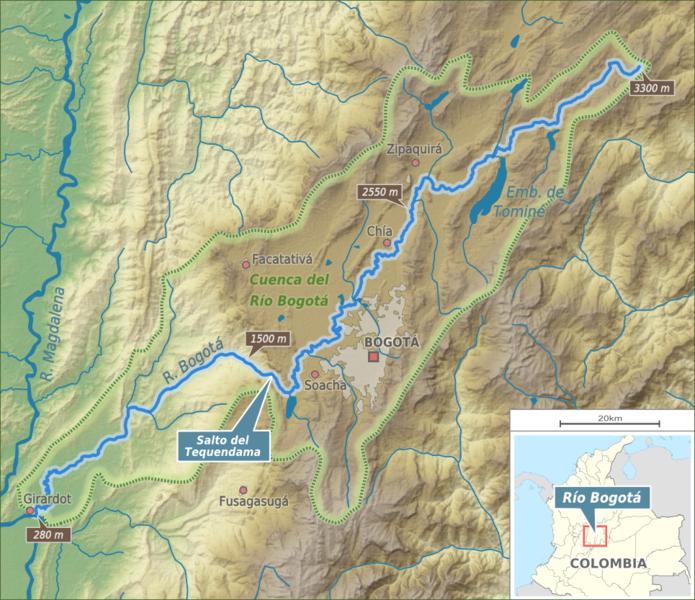

Bogota is located in the Bogotá Sabana (savannah) atop the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, a high plateau of the Cordillera Orientalles, the easternmost range of the main ridges of the Colombian Andes. The average altitude of the Altiplano is about 2,600 m (8,500 ft). The savannah and the city are bordered to the East by the Cerros Orientales (the Eastern Hills), a mountain range extending from north-northeast to south-southwest with elevations between from 2600m to 3600m. Its high elevation gives it a temperate climate with daily temperatures ranging from 8 to 20 °C. [24] In its location within the Andean Atlantic subsystem, Bogotá lays in the path of humid air that rolls in from the Orinoquía and the Amazon. This humid air becomes orographic precipitation as it climbs the eastern mountains. Whereas the north eastern zone of the Bogota Capital district receives between 500 and 1000 mm of precipitation per year, the Páramo de Sumapaz in the Southern part of the district receives between 1000 and 15000 mm, and the areas to the east of the city receive as much as 2000 mm per year [25] .

The geology of the Eastern Cordillera surrounding Bogotá is primarily of sedimentary rocks deposited during the Cretaceous and Tertiary onto a basement of Paleozoic rocks with low metamorphism. [26] During the Pleistocene epoch, the Eastern Hills were covered by glaciers that fed a lake that covered much of the Bogota Sabana. Today the many wetlands that still exist (many have been filled-in or drained for agriculture and development) are the final reminders of this prehistoric lake. [27] The climate of the Last Glacial Maximum gave rise to the development of the páramo ecosystems and Andean forests throughout the region .

The Rio Bogotá origin ates in the Guacheneque Páramo, located in the mountains of Villapinzón, runs south through the savannah and Bogotá, dives off of the Tequendama Falls 32 km south of Bogotá, and eventually joins the Magdalena River near the town of Girardot.

The archaeological record shows strong evidence that hunter-gatherers occupied the Sabana de Bogotá as early as 12,000 BP. That their tools were exclusively made of raw materials local to the savannah indicates that they spent much of their time there rather than just moving through. These groups changed the ecosystems of the region through various practices that modified the growth patterns of the resources they relied on including cultivation. The first evidence of cultivation of corn dates back to 3,300 AP .

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense corresponds with the historic territory of the indigenous Muisca . Pre-Muisca groups were present in the Sabana de Bogotá around 1,200 A.P. in widely dispersed settlements on both sides of the Rio Bogotá. During the Early Muisca Period (200 AD to 1,000 AD) and the Late Muisca Period (1,000 AD to 1,600 AD), their settlements in present-day Cota and Suba areas grew substantially. [28]

Although the Muisca settlements were primarily oriented toward the Rio Bogotá, the many wetlands of the region were also very important to the Muisca for gathering food, including fish. The archaeological record shows that the Muisca built artificial ridges/mounds separated by channels in the wetlands. They cultivated these ridges, taking advantage of the fertility of the wetlands, while ditches and channels that extended outward from the wetlands were used to irrigate fields beyond. This ridge and channel system provided resilience to frost and drought thanks to the ubiquitous presence of water and to flooding thanks to the extensive drainage system. Colonial documents confirm that these practices were used at the time of conquest. The archeologist Boada identified an area between the eastern bank of the Bogotá River and the Autopista Norte and from the Jaboque wetland to the Guaymaral airport of close to 7500 hectares that had been shaped this way. [29] The wetlands were also important to the Muisca as sacred sites of worship as many of their gods and origin stories were related to water. They located their temples at lagoons and water sources . [30]

The Bogotá Sabana was known as Bacatá in Chibcha, the Muisca language. The Muisca were called “The Salt People” because they extracted and traded salt in Zipaquirá, Nemocón, Tausa and other areas on the Bogotá savanna. Salt extraction was only performed by the Muisca women. The Muisca also mined emeralds and gold and were skilled goldsmiths. [31] It is said that the legend of El Dorado began with stories of the Muisca rite of passage for newly chosen leaders who would paddle out into the middle of a sacred lake and jump in wearing nothing but a dusting of gold as their subjects watched from the shore. Lake Guatavita, located about 70 km north of Bogotá, was one of these sacred lakes. It seems that hyperbole transformed the golden ruler into a golden city in the alluring myth. [32]

Although the Muisca were largely self-sufficient because of their advanced agricultural methods, they did trade with their neighbors, particularly the Guane and Lache in the north and northeast and the Guayupe, Achagua and Tegua in the east, for more tropical and subtropical products they could not grow (such as avocados and cotton).

The Spanish conqueror Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada and his troops encountered the Muisca in the Sabana de Bogotá as he traveled from the Caribbean down the Magdalena River. His forces defeated Tisquesusa, the zipa—the Muisca ruler of the Sabana--in April 1537. It is estimated that 65-80% of the Muisca died due to European diseases. De Quesada established the New Kingdom of Granada with Santa Fe de Bogotá as the capital on August 6, 1538. The colonisation and evangelization of the Muisca led to the harsh repression of traditions and traditional life ways including crops. Eventually the Muisca were moved to reserves.

The population of Bogota grew rapidly during the late 16th century. Political unrest plagued the Spanish colonies in America during the 18th century. Under the leadership of Simón Bolívar, the Kingdom of New Granada finally won independence from Spain in 1819. Bolivar united Venezuela, Quito and Nueva Granada under the new state of Gran Colombia, though it was unfortunately short lived, dissolving in 1830.

In 1851 lands that had previously been designated as Muisca Reserves in Zipaquirá, Nemocón, Tabio, Tocancipá, Cota, Suba, and elsewhere were confiscated and privatized. As the hacienda system of land ownership replaced the collective land tenure model of the Muisca in the 18th and 19th centuries in these lands and others across the Bogotá sabana, the wetlands were dried out and developed. Eucalyptus and pines were introduced, extensive drainage ditches and canals were built, and the Rio Bogotá was largely confined by built embankments to prevent winter flooding. The pre-conquest riparian alder forests were replaced with willows whose roots further reinforced the embankments. [33]

The arrival of new technologies and new crops ushered in the industrialization of agriculture in the Bogotá Sabana during the first decades of the 20th century, in a process that has been called the “Europeanization of the Sabana de Bogotá.” Wheat, corn, barley and potatoes were grown in large monocultures, while new timber species and grazing breeds led to extensive conversion of wetlands and intact ecosystems to plantations and pastures. The few remaining wetlands were further degraded through contamination from agrochemicals and pesticides. Where there were once more than 50,000 hectares of wetlands, only 800 ha remain. [34]

Today, the Metropolitan Area of Bogotá on the Bogotá savanna hosts more than ten million people. Bogotá is the biggest city worldwide at altitudes above 2,500 metres (8,200 ft). The many rivers on the savanna are highly contaminated and efforts to solve the environmental problems are conducted in the 21st century.

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

- The long term water supply is threatened

- Paramos are being developed

- The many rivers of the Bogotá savannah are highly polluted

- Few wetlands remain; urban wetlands do not provide great habitat because they are degraded;

- Air quality

- Mining

- Hazardous Settlement Patterns

- So-called “pirate” developers are subdividing land illegally and hooking into the river system leading to uncontrolled, widely dispersed points of contamination throughout the city

- Some of these informal settlements have developed in areas of high risk including steep slopes and floodplains

- Waste Management

- Unplanned suburbanization is leading to dispersed settlements on important agricultural lands and in ecologically sensative and valuable areas

- Although some of the hills and wetlands are protected, they face a lot of challenges:

- Invasive Species

- Forest Fires

- Heavy trail usage

Ecological & Biodiversity Assessment of the Capital District

The 2010 Management Policy for the Conservation of Biodiversity in the District Capital (Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital) conducted an ecological survey of the Capital District and its primary areas of influence (which it defined as the conservation corridor Páramo de Guerrero- Chingaza – Cerros Orientales – Sumapaz).

Within the rural zones of the Bogotá Capital District, in 2010 páramo vegetation constituted 50.8% of the land cover, pastures 11.8%, and the high Andean forests 4.5%. In the urban matrix, the Capital District contains 15 types of coverage. The built up area accounted for 45.93% of land cover, pastures for 22.11%, and the road network, railroads and associated land accounted for 19.78%. [35]

The assessment found that in the urban region of the District loss of habitat and fragmentation and degradation of ecosystems had led to a severely diminished presence of wildlife. Generalist species tolerant of disturbance, as well as invasive and domestic species such as pigeons, dogs, rodents and cats constituted the dominant fauna in the urban area. According to the assessment, parts of Usaquén, Suba and la Candelaria localities offered the best quality habitat at the time. [36]

For all the municipalities and sectors that comprise the rural area of the Capital District and its regional context, 2358 plant species are reported. The highest number of species (852) were documented in Chingaza National Natural Park (PNN).

Within the rural areas of the district, delimited areas within the municipalities of Chipaque and Une, as well as the Eastern Hills of Bogotá, present the lowest diversity of flora (like the areas of low diversity in the Eastern Hills correspond with mining activities and present or recently relocated informal settlements).

The study identified 38 threatened plant species that were listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature-IUCN and the Red Books of Colombia.

The study also identified significant numbers of endemic species. Twenty three families of plants represented by 44 species broken down according to their endemism as follows:

- 36 species endemic to the páramos of Colombia

- 5 species endemic to the paramos and high Andean regions of the Eastern Cordillera

- 3 species endemic to the Sumapaz region

The plant richness in the District Forest Areas (AFD) and Los District Ecological Parks of Mountain (PEDM), exceeds to 459 species. The PEDM-Entrenubes (327 sp) and the AFD Páramo Los Salitres (210) sp) are the district protected areas with the greatest diversity of flora, in contrast to the AFD Restoration Corridor Yomasa Alta (34 sp) and the AFD-Cerros de Suba (30 sp). [37]

Invasive Species

In their assessment for the District Biodiversity Policy, Conservation International and the Secretaria Distrital de Ambiente found that invasive species pose a serious threat to biodiversity in the Capital District.

Domestic species such as pigs, dogs and cats were identified as the most damaging category of invasive species as they alter the composition and structure of native biodiversity and can act as vectors for diseases and pests. Livestock compact soil, destroy understories, and contaminate surface water with high levels of nutrients. In terms of aquatic invasives, trout ( Oncorhynchus mykiss ) that have gotten established in streams and have altered local ichthyofauna and led to a serious decline in the populations of sensitive amphibian species. Lithobates catesbeianus , an invasive bullfrog, is both an aggressive predator of indigenous vertebrates and a vector for the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrodatidis, which kills amphibians.

Thorny reed ( Ulex europaeus ) and smooth retamo ( Teline monspessulana ) are particularly problematic invasive plants in the rural areas in the district. They are both highly competitive and adaptable growers that have strong allelopathic effects (they suppress the growth of other plants, including indigenous plants). [38]

Use Of Biodiversity In The Capital District

The city of Bogotá is one of the country’s main centers of marketing for wild fauna and flora and products made from these. For wildlife, permits have been granted to businesses that commercialize, transform and process complete individuals or in parts. These permits are for species that are distributed within Colombia (eg, butterflies, babillas, crocodiles, among others) as well as for others that are exported for processing (e.g. chinchillas, pythons and ostriches). The majority of the species that have been seized that are sold as pets come from other parts of the country as very few of them have a population within the Capital District. In terms of plants, as of 2010, 383 species of plants had been identified as having some type of known use; 87 of these occur naturally in the Capital District. The SDA has the great responsibility to monitor and oversee the forest production chain within the district and to destination end of large volumes of wood from different regions of the country (SDA, 2007). The agency has reported around more than 2450 businesses make up the forestry processing and marketing industry. [39]

Wetlands in Bogotá Capital District and the Bogotá-Sabana Region

Today, the once more than 50,000 hectares of wetlands have been reduced to 800 ha.

In those that do remain, according to the Policy on Biodiversity for the Bogotá Capital District, the richness of flora in the wetlands of the urban area of the District Capital amounts to approximately 400 species, including morphospecies. The La Conejera (253 sp) and Córdoba (210 sp) wetlands are richer and more diverse than Torca and Guaymaral (17 sp) and El Burro (16 sp). While the wetlands of Torca/Guaymaral, La Conejera and Córdoba provide habitat for local and migratory avifauna, the SDA found that significant ecological restoration is needed across the rest of the urban wetlands for them to provide quality habitat.

There is increasing popular and political awareness of the ecosystem value of wetlands. On the eve of his departure from office in August 2018, President Juan Manuel Santos declared that 15 wetlands in Bogota would be designated as protected Ramsar sites. The fifteen wetlands (Torca -Guaymaral, La Conejera, Córdoba, Tibabuyes or Juan Amarillo, Jaboque; Santa María del Lago, El Burro, Techovita or La Vaca, Ceiling, Chaplaincy, Meander Say, Tibanica, El Salitre, El Tunjo and La Isla) were grouped into a complex of 12 wetlands, their total area coming to 704 hectares (1740 acres).

Water Supply

The city of Bogotá, like much of Colombia, is dependent on páramos for water--one páramo in Chingaza National Park to the northeast of the city provides 70% of Bogotá’s water, and the rest comes from the Sumapaz and Guerrero páramos (located respectively to the south and the north of the city). Like páramos throughout the country, these are threatened by farming, coal mining, and climate change. [40]

There are two main aquifers underlying Bogotá. Only one of them--located within deposits of Cretaceous rocks of the Guadalupe group--holds water that is suitable for human consumption as the other aquifer within the Quaternary deposits has high levels of iron. The water in these aquifers infiltrates from drainage from the surrounding hills. As of 2010 there were 105 licensed wells in the district using 20,315.98 m3 / day (7'423,087.13 m3 / year). [41]

Need to expand on the following:

- The rivers of the Bogotá Sabana are highly polluted… need to expand on this

- Western parts of the city are low lying--lower than the Rio Bogotá

- Bogotá bucked the trend of privatizing water utilities [42]

- Two new water treatment plants--Salitre and Canoas

- Disturbed hillsides have desertified…

- Based on the rainfall and temperature, the Capital District and its area of influence is categorized as dry to very dry, which makes this area highly vulnerable to desertification [43]

The CAR undertook a six-year river improvement project along 52.2 km of the Río Bogotá that widened the river channel in places from 30 to 60 meters and constructed raised banks. The expected water quality improvements that were hoped for in implementing the project were not immediately true. In fact, concerns were raised in 2016 as the project neared 90% completion that levels of mercury were higher than levels permitted by WHO in Bosa and Suba. The contamination leading to critical pollution levels was blamed on the negligent disposal of toxic consumer products such as light bulbs and batteries as well as industrial effluents including pesticides. Pollution levels in the Río Bogotá were so high that the contamination levels in the Magdalena River are significantly elevated beyond the point where the Bogota joins the Magdalena. [44]

Waste Management

Colombia’s municipal waste management systems rely on informal and independent recyclers ( recicladores ). In Bogotá, the 14,000 people who rely on informal cycling for their livelihoods collect 55% of the city’s recycled waste. The city recognized waste pickers as public servants in 2013 and started to pay recyclers who collect and deliver material to the 141 scrap dealers in the city. [45]

Mining

Mining is a common activity in the Eastern Hills. Although most of the area is a dedicated natural reserve, in 2009 sixty-two quarries existed within the reserve of the Eastern Hills. The total surface of mining activities in 2006 was 120 hectares (300 acres), less than 1 percent of the total area of the Eastern Hills. Extensive mining areas are in La Calera and Usme. The Soratama quarry, named after the indigenous Muisca woman Zoratama, in the northern part of the Eastern Hills, was used for decades until it was closed in 1990. During the 2000s and in recent years, the location of the former quarry has been destined for geomorphological restoration.

Natural Threats

“Bogotá is exposed mainly to natural hazards such as landslides, floods and seismic events. It is also exposed to non-intentional human caused hazards, forest fires for example, and structural hazards, technological accidents (toxic and fuel spills, gas explosions, etc.), and incidents taking place during the congregation of large masses. These events are common to the Andean region.” [46]

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

According to the Atlas of Urban Expansion, in the 2001-2010 period, of Bogotá’s residential land use settlements, 5% were atomistic settlements, 26% where informal subdivisions, 18% were formal subdivisions, and 51% were housing projects. Relative to regional and global averages, the proportion of atomistic settlements is significantly lower and the proportion of housing projects is significantly higher. [47] [48]

The municipalities surrounding Bogota are growing/gaining population much faster than the city itself. During the last 30 years, the population of Bogotá has almost doubled, while in the city's surrounding areas this growth has been 2.8 times [49]

The city experienced a population explosion due to the conflict between the Colombian government and the FARC . Various sources estimate the number of internally displaced people in metropolitan Bogota at about 600,000 and many of them live in the municipality of Soacha. In 2015 the director of the National Planning Department of Colombia (DNP) stated that 78% of internally displaced people from the conflict between the Colombian government and the FARC guerilla movement are living in medium and large cities, and that 2 million internally displaced people live in Bogotá. [50]

A shortage of developable land in Bogotá (and therefore high prices for land) paired with the low supply and prohibitive cost of Social Housing options for the poorest sectors has driven many residents of the Bogotá metro area into illegal housing arrangements. According to the UNDP 1,500,000 people live in illegally developed areas and homes across 23.6% of the city area. [51]

Governance

Colombia is a unitary republic that is divided into thirty two departments (provinces) and the Bogotá Capital District. Each department is further subdivided into municipalities. Bogotá Capital District is located within the Cundinamarca Department, but administered separately and autonomously with the same administrative status as the departments of Colombia. Even though Bogotá is not legally part of Cundinamarca Department it is the capital of the department.

The 1991 Constitution of Colombia values environmental health highly, defining the protection of natural resources as a basic purpose of the state and asserting a collective right to a healthy environment. Protection of the environment is one of very few cases in which the national government can limit “economic freedom.” [52]

The Metropolitan Area of Bogotá includes Bogotá Capital District and 17 surrounding municipalities in the Department of Cundinamarca: Soacha, Facatativá, Zipaquirá, Chía, Mosquera, Madrid, Funza, Cajicá, Sibaté, Tocancipá, La Calera, Sopó, Tabio, Tenjo, Cota, Gachancipá and Bojacá. The urban area of Soacha has conurbated with Bogotá’s localities of Bosa and Ciudad Bolívar. Although there is no legal or official designation of the Metropolitan Area, the term is used to describe the de facto extension of the urbanized area of Bogotá. The Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE, National Administrative Department of Statistics) does refer to the area as the “Área Metropolitana de Bogotá'' in the census. When the Metropolitan Area of the Sabana is referenced in official documents, it is meant to refer to the urbanized areas of the geographical region of the Bogotá Sabana. [53]

Bogotá Capital district has an area of 163,660.94 ha, of which 23.41% is urban area and 76.59% is rural. [54] It is is divided into 20 localities, Usaquén, Chapinero, Santa Fe, San Cristóbal, Usme, Tunjuelito, Bosa, Kennedy, Fontibón, Engativá, Suba, Barrios Unidos, Teusaquillo, Los Mártires, Antonio Nariño, Puente Aranda, La Candelaria, Rafael Uribe Uribe, Ciudad Bolívar and Sumapaz.

The District Council is the city’s main authority which expresses its legislative authority by issuing agreements. Its members are elected on a three year cycle, and each seat represents 150,000 residents. An important role of the District Council is the evaluation and approval of the Development Plan for the District, which is set out at the beginning of each Mayor’s term.

The Mayor is elected for periods of three years without the possibility of being elected for a second consecutive term.

The 20 localities of the Capital District are governed by a structure mirroring the overall governance of the city with local councils called Juntas Administradoras Locales (JAL; Local Administrative Assemblies) and local Mayors. JALs are also elected on a 3 year cycle, while local mayors are named by the City Mayor out of a group of three options put forward by the JAL. [55]

City Policy/Planning

History of Planning

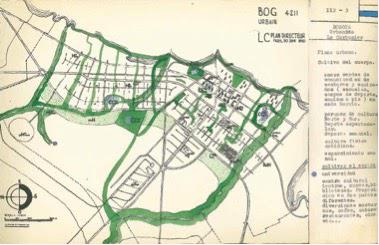

Left: Corbusier’s 1951 Open Space Plan for Bogotá [69] Right: Corbusier’s 1951 Circulation Plan for Bogotá [70]

An unrealized 1951 Master Plan of Bogotá by Le Corbusier introduced the idea of a polycentric regional network for Bogotá and its surrounding territories. [71] The 1961 Pilot Road Plan based on a planning approach from the US and Europe called the Urban Transport Planning Process had greater success in shaping the development of Bogotá as close to 60% of the plan was realized and many of the main corridors of the city today were implemented as a result of this plan.The plan revisited ideas from Corbusier’s Master Plan including a mixed road network and ring roads. The plan made one of many subsequent attempts to define a ring road that would serve as an outer boundary to control Bogotá’s growth. It also called for an public transportation rail system to support dense development and improved connectivity and consolidation of the city; this part of the plan was neglected in favor of funding further road development. [72]

Lauchlin Currie undertook a study of Bogotá’s urban development in February 1962, which ultimately widened its scope to consider Bogotá’s growth in the context of the rate and pattern of growth in Colombia and made recommendations for a national urban policy aimed at preventing sprawl. This was followed by a subsequent study in 1966-1967 for then-mayor of Bogotá Virgilio Barco which pushed the idea of “cities-within-cities” that aimed to create “self-contained nuclei within the metropolitan areas that could promote a much better matching of jobs, residences, and community facilities...minimizing transportation costs,” while capitalizing on the economic efficiencies of large cities. He returned to Bogotá in May 1971 to develop what was called the Phase II study. Whereas Phase I had been carried out by a firm of transport planners and engineers and had not gone beyond making recommendations to meet transport requirements extrapolated from existing growth trends, Currie pursued a planning framework that would prevent traffic generation, prevent urban sprawl patterns based on private automobile ownership, and protect the valuable agricultural lands of the Sabana. [73]

The development of Transmilenio during the first Peñalosa government and the subsequent investment in the secondMockus administration, led to the consolidation of BRT as an instrument for reorganising urban transport in Bogotá (Skinner, 2004), as well as considering an integrated public transport system within the city's boundaries, and even for some routes connecting adjacent municipalities. [74]

Post Penalosa mayors focused on left programs such as hunger reduction, child education and welfare---but stopped investing in transportation; Moreno stopped investing in Transmilenio because he wanted to build a metro, but his metro project was embroiled in scandal.

POT

According to national law, the POT must be updated every 12 years. The first POT was adopted in 2000. The current update of the POT has been in default for 6 years. [75]

In November 2018, the Secretaria Distrital de Planeación submitted an updated POT for review to the Regional Autonomous Corporation of Cundimarca (CAR) and the Secretaria Distrital de Ambiente (SDA). It also initiated a 100 day citizen participation phase to get feedback from Bogotanos in each of the Unidades de Planeamiento Zonal (UPZ; Zonal Planning Units) and rural zones in the Bogotá Capital District. [76]

Once the environmental authorities approve the POT, it will go to the Consejo Territorial de Planeación Distrital (TCDC; District Planning Council) for approval.

The Secretary of Planning, Andrés Ortiz, sees four main challenges facing the city that the new POT needs to address: to make Bogotá an eco-efficient city, developed in a dense, compact manner; to make the city more equitable and democratic, guaranteeing rights to the environment, health and education to all Bogotanos; to make both the region and the city competitive, and finally to develop institutions that guarantee stable governance between Bogotá and the municipalities of La Sabana. [77]

Zoning

Secretaria de Planeación Distrital

The Zone Planning Units are the result of participative exercises where urban actors with certain homogeneity regarding economic form and functions, together with the entities led by the Secretaria de Planeacion Distrital (District Planning Secretariat), define detailed regulations of occupation and use, within the framework of the District Land Use Planning. In these exercises the starting criteria include those of safety in localisation and mixture of activities and infrastructure.

Moreover, work is currently being’ carried out on the elaboration and agreement of a district policy for the comprehensive management of protected land, which is the only one that by law is restricted from the possibility of urbanisation. It is delimited in Bogotá by its POT and includes landscape and environmental conservation areas, high hazard areas and land reserved for the construction of domiciliary public services.

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Colombia is the most biodiverse country per square kilometer. [78]

Colombia submitted its first NBSAP titled the National Biodiversity Action Plan (PNB) in 1996. An updated plan called the Política Nacional para la Gestión Integral de la Biodiversidad y sus Servicios Ecosistémicos [79] followed in 2012 (PNGIBSE; National Policy for the Integral Management of Biodiversity and its Ecosystemic Services). The updated plan reflects on the need to strengthen links between national biodiversity policy with other sectoral policies and to increase community participation in national biodiversity and ecosystems management. The objective of the PNGIBSE is to “promote the Integral Management of the Conservation of Biodiversity and its Ecosystemic Services so that the resilience of socio-ecological systems is maintained, on national, regional and local scales, taking into account scenarios of change and through the joint, coordinated and concerted action of the State, the productive sector and civil society.” [80] The plan suggests that the most concrete foreseeable and desirable expression of implementing the PNGIBSE is to be the territorial ordering of the country, which it proposes would be an effective political-administrative tool for future planning and development.

Conservation and Care of Nature: Need for In situ and ex situ conservation in wild and transformed areas regardless of their protection states and across representative landscapes that allows for the maintenance of viable populations of plants and animals such that the resilience of socio-ecological systems as well as the supply of ecosystem services are maintained.

Governance and the Creation of Public Value: Need to strengthen the relationship between the State and citizens in order to integrally manage biodiversity and its ecosystem services so that citizens come to perceive biodiversity as an irreplaceable asset that protects and improves quality of life.

Biodiversity, Economic Development, Competitiveness and Quality of Life: Need to incorporate biodiversity into sectoral planning and to promote co-responsibility between the government and the private and public sectors to incentivize sustainable methods of production, extraction, settlement, and consumption.

Biodiversity and the Management of Knowledge, Technology and Information: Need to generate, disseminate, and integrate knowledge and technological developments across systems of knowledge production to better guide decision making regarding biodiversity and ecosystem management.

Management of Risk and Supply of Ecosystemic Services: Need to stem the threats associated with environmental change due to the loss and transformation of biodiversity and its associated ecosystem services as well as to variability and climate change so as to protect socio-ecosystemic resilience.

Biodiversity, Co-Responsibility, and Global Commitments: Need to strengthen Colombia’s position in the international community as a megadiverse country whose ecosystem services are vital on a global scale while also undertaking actions to contribute to the global fight against biodiversity loss and climate change.

The Plan de Acción de Biodiversidad [81] (2016-2030) (PAB; Biodiversity Action Plan) is an implementation plan for the PNGIBSE. The PAB is aligned with the six strategic directions of the PNGIBSE stated above.

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The Nature Conservancy’s Bogotá Water Fund “Agua Somos” (We are Water) was launched in 2008. The fund sources from many different funding sources including private sector donations, philanthropic and voluntary contributions from water treatment plants. TNC has found that the latter groups could save as much as $4 million annually by investing proactively in in watershed protection. The fund takes a multi-pronged approach to safeguarding Bogotá’s water from supporting people who live in sensitive areas to shift their lifeways toward more sustainable practices, to compensating landowners for conserving ecosystems such as forests and páramos, on their land, and to improving protected area management. It aims to improve water governance by creating a single operational entity that unites the efforts of previously disjointed water agencies. [82] [83]

Biocomercio Sostenible provides technical assistance to develop a sustainable biotrade market. The program supports communities and medium-sized businesses develop sustainable use of local biodiversity. Examples include the harvesting and processing of Amazonian fruit, honey, flora and fauna . [84]

”The Chingaza-Sumapaz-Guerrero Conservation Corridor, designed by a participatory process led by Conservation International (CI) Colombia and the Bogota Water Supply Company, protects and manages the páramos of Chingaza to provide multiple benefits. A landscape-level program prioritizes some areas for conservation, others for restoration, and others for natural resource use, ensuring that the Corridor’s páramo wetland ecosystems can sustainably provide clean water for the 8 million residents of Bogotá farther downstream, habitat for endemic species, and land and irrigation for local communities well-being.” [85]

Nodos de Biodiversidad: Investigación y Apropiación Social de la Biodiversidad en la Región Capital [86] [87]

This is a joint project of the Jardín Botánico de Bogotá José Celestino Mutis, the Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente, and the Instituto Alexander von Humboldt. Its aim is to promote research as well as social awareness and engagement in environmental restoration and protection. It uses a framework of biodiversity nodes to structure research as well as to encourage social awareness, valuation, and sustainable use of the ecosystem services of these nodes. The nodes have been chosen as sites that will undergo extensive ecological restoration, that will be closely studied, and that will serve as platforms for public education. The budget for the project is 14 billion pesos (800 million US dollars), and has secured about 80% of the necessary funding.

Plan Regional Integral de Cambio Climático : a n interinstitutional platform that seeks to generate applied research and technical knowledge aimed at making decisions to confront climate change. [88]

Sendero de Las Mariposas: The Trail of Butterflies

The Sendero de Las Mariposas is a proposed 160 km tourist and recreation trail that would connect Lagos de Torca to Usme that will also act as a fire break. The development of the trail will include building a 300-m pedestrian bridge between Monserrate and Guadalupe, a gondola in Usuquén, a connection to Tominé Park, 60 kilometers of cycling paths, and infrastructure for water recreation. The trail will connect the Guerrero and Sumapaz páramos, as well as the Chingaza complex. The development of the Sendero de Las Mariposas will be an opportunity to make interventions in the intersecting creeks: Fucha, San Francisco, Arzobispo and Teusacá rivers, and the La Vieja, Las Delicias, Chicó and La Chorrera. The spokesperson of the Veeduría Cerros (a watch group for the Eastern Hills), María Mercedes Maldonado, however, says that the proposed trail goes against the land uses permitted under the current Management Plan for the Cerros Reserve. The project is currently at the stage of environmental studies and design. [89]

Public Awareness

At the opening of a new national park, Bahía Portete, in 2014 president Santos declared that “biodiversity is to Columbia as oil is to the Arabs” and that that made conservation a priority for the country. [90]

Wetlands in Bogota: A group of young activists, most of whom work as volunteers, has created an extensive documented Bogota’s wetlands, including those that are recognized by government entities and those that are not. They map the city’s wetlands, write articles, teach classes and lead tours of the wetlands to raise awareness of the importance of preserving these wetlands. They were awarded the 2015 Ramsar Convention Award to Young Wetland Advocates. [91] [92]

Bogotanos feel very strongly about the proposed development of the Van der Hammen Reserve. This has been a contentious issue during the approval process for the current POT.

[1] Google Earth, https://earth.google.com/web/@4.64829753,-74.10780672,2550.4071382a,92714.72290565d,35y,0h,0t,0r/data=CkwaShJCCiUweDhlM2Y5YmZkMmRhNmNiMjk6MHgyMzlkNjM1NTIwYTMzOTE0GbdQQ2UN2BJAIWiTwyedhFLAKgdCb2dvdMOhGAEgASgC (Accessed January 4, 2019).

[2] The Nature Conservancy, “Stories in Colombia: Water Security. Investing in nature to secure fresh water for Colombia’s most at risk cities,” https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/latin-america/colombia/stories-in-colombia/colombia-water/ (Accessed January 1, 2019).

[3] “Magdalena Valley Montane Forests Land Use Data,” Global Species, https://www.globalspecies.org/geographics/landuse/211/19 , Accessed December 21, 2018.

[4] CEPF, “Tropical Andes: Species,” https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tropical-andes .(accessed December 20, 2018).

[5] CEPF, “Tropical Andes: About this Hotspot,” https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tropical-andes . (accessed December 20, 2018).

[6] CEPF. “Tropical Andes - Species.” Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tropical-andes/species .

[7] CEPF, “Tropical Andes: Threats,” https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tropical-andes .(accessed December 20, 2018).

[8] Ibid.

[9] CEPF, “Tropical Andes: About this Hotspot,” https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tropical-andes . (accessed December 20, 2018).

[10] WWF. “Northern South America: Western Colombia | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0136.

[11] “Yellow-Eared Parrot.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 15, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[12] “Mountain Tapir.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 15, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[13] WWF. “Northern South America: Western Colombia | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0136.

[14] “Magdalena Valley Montane Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60136.

[15] WWF. “Northern South America: Central Colombia and Northeastern Venezuela | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0118.

[16] “Spectacled Bear.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 15, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[17] WWF. “Northern South America: Central Colombia and Northeastern Venezuela | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0118.

[18] “Cordillera Oriental Montane Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60118.

[19] Michael Altenhenne, “Bogotá’s unique water source at risk,” DW (May 5, 2015), https://www.dw.com/en/global-ideas-colombia-paramos-biodiversity-water-supply/a-18428938.

[20] Santiago Mardiñán, Andres Cortés, and James E. Richardson, “Páramo is the world’s fastest evolving and coolest biodiversity hotstpot,” Frontiers in Genetics 4:192 (2013), https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2013.00192/full.

[21] The Nature Conservancy: Urban Water Blue Print, “Bogotá, Colombia,” http://water.nature.org/waterblueprint/city/bogota/#/c=9:4.61749:-73.94348 (Accessed December 20, 2018).

[22] Michael Altenhenne, “Bogotá’s unique water source at risk,” DW (May 5, 2015), https://www.dw.com/en/global-ideas-colombia-paramos-biodiversity-water-supply/a-18428938.

[23] “Northern Andean Páramo.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/61006 .

[24] Reinhard Skinner, “City profile: Bogotá,” Cities 21, 1 ( 2004): 73.

[25] “Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital,” Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente de Bogotá (2010), Editorial Panamericana, Formas e Impresos. Bogotá, Colombia. pp 13-14.

[26] Citation: Andean risk...

[27] Citation?

[28] Henry Margoth Santiago Villa, “Importancia Histórica y Cultural de los Humedales del Borde Norte de Bogotá (Colombia),” rev.udcaactual.divulg.cient. [online]. 2012, vol.15, n.1, pp.167-180, <http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-42262012000100018&lng=en&nrm=iso>. ISSN 0123-4226 (accessed January 4, 2019).

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Citation? This is mainly from wikipedia :/

[32] Jago Cooper, ”El Dorado: The truth behind the myth,” BBS News (January 14, 2013), https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20964114 (Accessed January 4, 2019).

[33] Henry Margoth Santiago Villa, “Importancia Histórica y Cultural de los Humedales del Borde Norte de Bogotá (Colombia),” rev.udcaactual.divulg.cient. [online]. 2012, vol.15, n.1, pp.167-180, <http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-42262012000100018&lng=en&nrm=iso>. ISSN 0123-4226 (accessed January 4, 2019).

[34] Henry Margoth Santiago Villa, “Importancia Histórica y Cultural de los Humedales del Borde Norte de Bogotá (Colombia),” rev.udcaactual.divulg.cient. [online]. 2012, vol.15, n.1, pp.167-180, <http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-42262012000100018&lng=en&nrm=iso>. ISSN 0123-4226 (accessed January 4, 2019).

[35] “Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital,” Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente de Bogotá (2010), Editorial Panamericana, Formas e Impresos. Bogotá, Colombia. pp Available: http://ambientebogota.gov.co/documents/10157/0/politica_biodiversidad_baja.pdf .

[36] Ibid.

[37] “Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital,” Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente de Bogotá (2010), Editorial Panamericana, Formas e Impresos. Bogotá, Colombia. pp Available: http://ambientebogota.gov.co/documents/10157/0/politica_biodiversidad_baja.pdf .

[38] “Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital,” Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente de Bogotá (2010), Editorial Panamericana, Formas e Impresos. Bogotá, Colombia. pp Available: http://ambientebogota.gov.co/documents/10157/0/politica_biodiversidad_baja.pdf .

[39] “Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital,” Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente de Bogotá (2010), Editorial Panamericana, Formas e Impresos. Bogotá, Colombia. pp Available: http://ambientebogota.gov.co/documents/10157/0/politica_biodiversidad_baja.pdf .

[40] Lucy Sherriff, “Why Bogotá Should Worry About Its Water,” CityLab (June 13, 2018), https://www.citylab.com/environment/2018/06/why-bogota-should-worry-about-its-water/562655/.

[41] “Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital,” Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente de Bogotá (2010), Editorial Panamericana, Formas e Impresos. Bogotá, Colombia. pp Available: http://ambientebogota.gov.co/documents/10157/0/politica_biodiversidad_baja.pdf .

[42] María Teresa Ronderos, “A tale of two cities,” International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (March 12, 2012)

[43] “Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital,” Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente de Bogotá (2010), Editorial Panamericana, Formas e Impresos. Bogotá, Colombia. pp Available: http://ambientebogota.gov.co/documents/10157/0/politica_biodiversidad_baja.pdf .

[44] Charlotte Mackenize, “Recent studies raise concerns about dangerous mercury levels in the city’s waterways and call for more effective waste management,” The Bogota Post , March 11, 2016, https://thebogotapost.com/bogota-water-mercury-rising/9829/ .

[45] “ Environmental Performance Reviews: Colombia,” The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2014, https://www.oecd.org/countries/colombia/Colombia%20Highlights%20english%20web.pdf , p 9.

[46] Regional Project of Risk Reduction in Andean Capital Cities: Bogota, Colombia, United Nations Development Programme, 2007, http://www.sasparm.ps/en/Uploads/file/2_%20Bogota.pdf (accessed December 20, 2018), p ???.

[47] Atlas of Urban Expansion, “Bogota,” http://www.atlasofurbanexpansion.org/cities/view/Bogota (Accessed December 20, 2018).

[48] Shlomo Angel et al., “Atlas of Urban Expansion-Volume 1:Areas and Densities,” NYU Urban Expansion Program, October 2016, p30).

[49] Luis A. Guzman, Daniel Oviedo, and Juan Panlo Bocrejo, “City profile: The Bogotá Metropolitan Area that never was,” Cities 60 (2017), p. 202.

[50] Patricia Weiss Fagan, “Columbia: urban futures in conflict zones,” NOREF Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre, April 2015, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/190417/14ca3d69d21a09923a5be3c07f4f5287.pdf.

[51] Regional Project of Risk Reduction in Andean Capital Cities: Bogota, Colombia, United Nations Development Programme, 2007, http://www.sasparm.ps/en/Uploads/file/2_%20Bogota.pdf (accessed December 20, 2018), p 23-26.

[52] Allen Blackman et al., “Assessment of Colombia’s National Environmental System (SINA)” Resources for the Future , October 2005, p 30.

[53] Somos Cundinamarca, “Área Metropolitana de Bogotá,” http://somoscundinamarca.weebly.com/aacuterea-metropolitana-de-bogotaacute.html (Accessed December 20, 2018).

[54] “Política para la Gestión de la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Distrito Capital,” Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente de Bogotá (2010), Editorial Panamericana, Formas e Impresos. Bogotá, Colombia. pp Available: http://ambientebogota.gov.co/documents/10157/0/politica_biodiversidad_baja.pdf .

[55] Nicolás Rueda-García, “The case of Bogotá D.C., Colombia,” Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements 2003 , p 7.

[56] Allen Blackman et al., “Assessment of Colombia’s National Environmental System (SINA)” Resources for the Future , October 2005, p.

[57] Regional Observatory for Development Planning of Latin America and the Caribbean, “ National Planning Department (DNP) of Colombia, ” https://observatorioplanificacion.cepal.org/es/instituciones/departamento-nacional-de-planeacion-dnp-de-colombia (Accessed January 2, 2019).

[58] https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Prensa/PND/Bases%20Plan%20Nacional%20de%20Desarrollo%20%28completo%29%202018-2022.pdf

[59] Volume 1: https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/PND/PND%202014-2018%20Tomo%201%20internet.pdf

Volume 2: https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/PND/PND%202014-2018%20Tomo%202%20internet.pdf

[60] Allen Blackman et al., “Assessment of Colombia’s National Environmental System (SINA)” Resources for the Future , October 2005, p 31.

[61] Sierra, Carlos A., Miguel Mahecha, Germán Poveda, Esteban Álvarez-Dávila, Víctor H. Gutierrez-Velez, Björn Reu, Hannes Feilhauer, et al. “Monitoring Ecological Change during Rapid Socio-Economic and Political Transitions: Colombian Ecosystems in the Post-Conflict Era.” Environmental Science & Policy 76 (October 2017): 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.06.011 .

[62] Sierra, Carlos A., Miguel Mahecha, Germán Poveda, Esteban Álvarez-Dávila, Víctor H. Gutierrez-Velez, Björn Reu, Hannes Feilhauer, et al. “Monitoring Ecological Change during Rapid Socio-Economic and Political Transitions: Colombian Ecosystems in the Post-Conflict Era.” Environmental Science & Policy 76 (October 2017): 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.06.011 .

[63] Corporacion Autonoma Regional de Cundinamarca, “Borrador POMCA Río Bogotá 2018,” https://www.car.gov.co/vercontenido/94 (accessed January 1, 2019).

[64] Corporacion Autonoma Regional de Cundinamarca, “Plan de Manejo Ambiental Reserva Forestal Protectora Bosque Oriental de Bogotá,” https://www.car.gov.co/vercontenido/173 (accessed January 1, 2019).

[65] Corporacion Autonoma Regional de Cundinamarca, “Plan de Manejo Ambiental de la Reserva Forestal Productora del Norte de Bogotá D.C.” https://www.car.gov.co/vercontenido/1152 (accessed January 1, 2019).

[67] Luis A. Guzman, Daniel Oviedo, and Juan Panlo Bocrejo, “City profile: The Bogotá Metropolitan Area that never was,” Cities 60 (2017), p. 204.

[68] Luis A. Guzman, Daniel Oviedo, and Juan Panlo Bocrejo, “City profile: The Bogotá Metropolitan Area that never was,” Cities 60 (2017), p. 204.

[69] O’Byrne, M.C, Sepúlveda Ortega, S.M (2010). Elaboración del plan regulador de Bogotá, Colombia: Universidad de los Andes, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, https://proyectodecada.wordpress.com/2015/05/07/la-trascendencia-del-plan-piloto-de-le-corbusier-en-colombia/

[70] Ibid.

[71] Luis A. Guzman, Daniel Oviedo, and Juan Panlo Bocrejo, “City profile: The Bogotá Metropolitan Area that never was,” Cities 60 (2017), p. 203.

[72] Ibid, p. 203.

[73] Roger James Sandilands, “The Life and Political Economy of Lauchlin Currie: New Dealer, Presidential Adviser, and Development Economist,” Duke University Press, Durham and London, 1990, pp 209, 260-271.

[74] Luis A. Guzman, Daniel Oviedo, and Juan Panlo Bocrejo, “City profile: The Bogotá Metropolitan Area that never was,” Cities 60 (2017), p. 204.

[75] Javier González Penagos, “Bogotá 2031: este es el modelo de ciudad,” El Espectador (August 18, 2018), https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/bogota/bogota-2031-este-es-el-modelo-de-ciudad-articulo-806886 (Accessed January 7, 2018).

[76] “En 15 días se empezará a discutir el POT de Bogotá en los barrios,” El Espectador (November 20, 2018), https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/bogota/en-15-dias-se-empezara-discutir-el-pot-de-bogota-en-los-barrios-articulo-824719 (Accessed January 7, 2018).

[77] Javier González Penagos, “Bogotá 2031: este es el modelo de ciudad,” El Espectador (August 18, 2018), https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/bogota/bogota-2031-este-es-el-modelo-de-ciudad-articulo-806886 (Accessed January 7, 2018).

[78] “La Alianza para la conservación de la biodiversidad, el territorio y la cultura logró incluir más de 6 millones de nuevas hectáreas protegidas al país,” World Wildlife Fund (December 21, 2018), http://www.wwf.org.co/?uNewsID=340670 .

[79] “National Policy for the Integral Management of Biodiversity and Its Ecosystemic Services NPIMBES (PNGIBSE) , ” Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of the Republic of Colombia (2012), Bogotá, Colombia.

[80] PNGIBSE__ P 82

[81] Source Needed

[82] The Nature Conservancy: Urban Water Blue Print, “Bogotá, Colombia,” http://water.nature.org/waterblueprint/city/bogota/#/c=9:4.61749:-73.94348 (Accessed December 20, 2018).

[83] Misty Herrin, “Stories in Colombia: Fund for Water Protection in Bogota,” The Nature Conservancy, https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/latin-america/colombia/stories-in-colombia/water-fund-bogota/ (Accessed January 1, 2019).

[84] “ Environmental Performance Reviews: Colombia,” The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2014, https://www.oecd.org/countries/colombia/Colombia%20Highlights%20english%20web.pdf , p 8.

[85] The Economics of Ecosystems & Biodiversity, “Managing the Andean páramo ecosystems to provide multiple benefits,” (October 11, 2013) http://www.teebweb.org/managing-the-andean-paramo-ecosystems-to-provide-mulitiple-benefits/ (Accessed December 20, 2018).

[86]

ConexionBio, “Proyecto Nodos de Biodiversidad

Investigación y Apropiación Social de la Biodiversidad en la Región Capital Bogotá,”

http://conexionbio.jbb.gov.co/el-proyecto/

(Accessed January 15, 2019).

[87]

El Sistema General de Regalías, “

Nodos de biodiversidad: Investigación y apropiación social de la biodiversidad en la región capital,”

http://regaliasbogota.sdp.gov.co:8080/regalias/portfolio/nodos-de-biodiversidad-investigaci%C3%B3n-y-apropiaci%C3%B3n-social-de-la-biodiversidad-en-la-regi-0

(Accessed January 15, 2019).

[88] IDEAM, “Plan Regional Integral De Cambio Climático Región Capital, Bogotá – Cundinamarca (PRICC)” http://www.cambioclimatico.gov.co/pricc (Accessed January 15, 2019).

[89] Monica Rivera Rueda, “El sendero que unirá a Usme con Torca,” El Espectador October 6, 2018, https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/bogota/el-sendero-que-unira-usme-con-torca-articulo-816461.

[90] “Colombia declares Bahia Portete to be national nature park,” San Diego Union Tribune (December 21, 2014), http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/hoy-san-diego/sdhoy-colombia-declares-bahia-portete-to-be-national-2014dec21-story.html.

[91] Fundación Humedales Bogotá, “Mapa de los Humedales de Bogotá”, http://humedalesbogota.com/mapa-humedales-bogota/ (accessed 7/11/2017).

[92] http://www.ramsar.org/activities/award-for-young-wetland-champions-2015