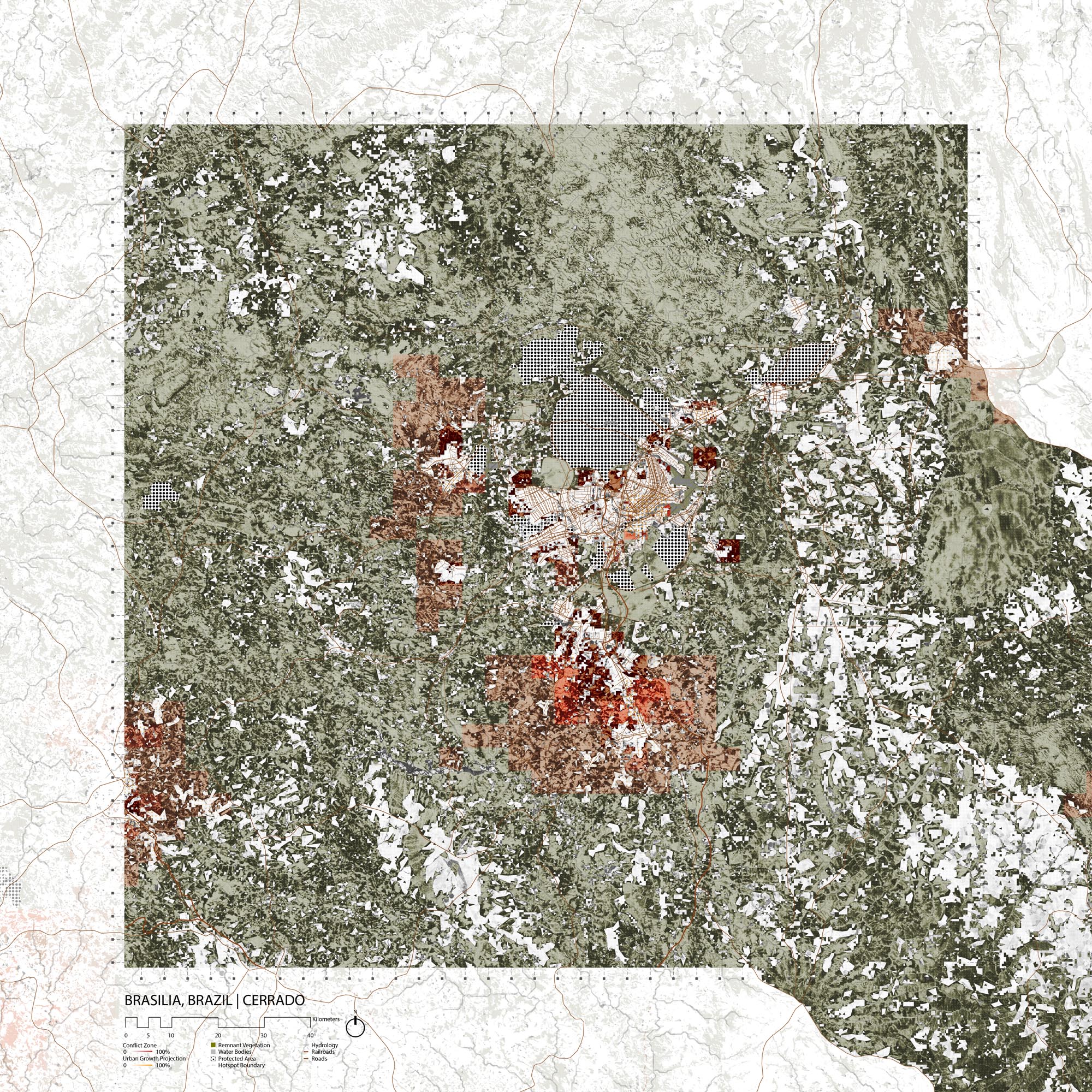

Brasilia, Brazil

- Global Location plan: 15.83OS, 47.92OW

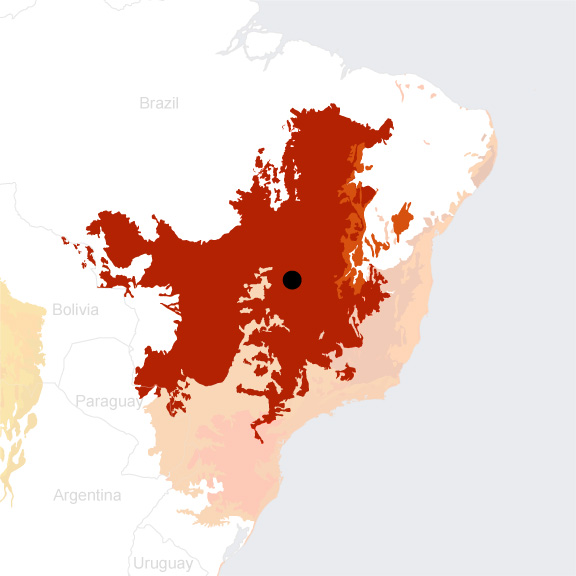

- Hotspot: Cerrado

- Population 2016: 4,235,000

- Projected population 2030: 4,929,000

- Mascot Species: giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla)

- Crops: soybeans, corn, and irrigated rice[1](arrived with the creation of Brasilia)

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Ololygon centralis

- Dendropsophus minutus

- Scinax squalirostris

- Boana crepitans

- Scinax x-signatus

- Rhinella marina

- Rhinella ocellata

- Leptodactylus podicipinus

- Rhinella granulosa

- Rhinella icterica

- Aplastodiscus perviridis

- Bokermannohyla pseudopseudis

- Boana punctata

- Adenomera martinezi

- Leptodactylus fuscus

- Leptodactylus mystaceus

- Leptodactylus latrans

- Leptodactylus troglodytes

- Odontophrynus salvatori

- Physalaemus cuvieri

- Pseudopaludicola mystacalis

- Pseudopaludicola saltica

- Pseudopaludicola ternetzi

- Chiasmocleis albopunctata

- Elachistocleis ovalis

- Siphonops annulatus

- Scinax tigrinus

- Lithobates catesbeianus

- Pithecopus hypochondrialis

- Boana geographica

- Trachycephalus nigromaculatus

- Boana raniceps

- Leptodactylus labyrinthicus

- Leptodactylus syphax

- Trachycephalus typhonius

- Proceratophrys vielliardi

- Scinax constrictus

- Ischnocnema penaxavantinho

- Siphonops paulensis

- Leptodactylus mystacinus

- Rhinella rubescens

- Allobates goianus

- Ameerega flavopicta

- Boana albopunctata

- Boana lundii

- Dendropsophus cruzi

- Boana faber

- Boana goiana

- Dendropsophus nanus

- Dendropsophus rubicundulus

- Pithecopus oreades

- Pseudis bolbodactyla

- Scinax fuscomarginatus

- Scinax fuscovarius

- Adenomera hylaedactyla

- Barycholos ternetzi

- Ischnocnema juipoca

- Leptodactylus furnarius

- Odontophrynus americanus

- Odontophrynus cultripes

- Physalaemus centralis

- Physalaemus marmoratus

- Physalaemus nattereri

- Proceratophrys goyana

- Pseudopaludicola falcipes

- Dermatonotus muelleri

- Leptodactylus sertanejo

- Pithecopus azureus

- Rhinella cerradensis

Mammals

- Thalpomys lasiotis

- Chrotopterus auritus

- Phylloderma stenops

- Leopardus colocolo

- Tadarida brasiliensis

- Marmosa demerarae

- Myrmecophaga tridactyla

- Nectomys squamipes

- Nyctinomops laticaudatus

- Oligoryzomys nigripes

- Euryoryzomys lamia

- Panthera onca

- Proechimys longicaudatus

- Pseudoryzomys simplex

- Diaemus youngi

- Oecomys bicolor

- Thylamys velutinus

- Callithrix penicillata

- Alouatta caraya

- Galictis vittata

- Platyrrhinus lineatus

- Phyllostomus discolor

- Lasiurus cinereus

- Cryptonanus agricolai

- Platyrrhinus helleri

- Tayassu pecari

- Pygoderma bilabiatum

- Thylamys karimii

- Nyctinomops macrotis

- Eumops delticus

- Eumops glaucinus

- Oligoryzomys moojeni

- Oecomys catherinae

- Oligoryzomys fornesi

- Rhynchonycteris naso

- Lasiurus ega

- Oligoryzomys eliurus

- Sapajus libidinosus

- Oecomys trinitatis

- Macrophyllum macrophyllum

- Potos flavus

- Cavia aperea

- Oxymycterus roberti

- Mazama nemorivaga

- Pecari tajacu

- Nasua nasua

- Juscelinomys candango

- Thalpomys cerradensis

- Saccopteryx bilineata

- Cabassous unicinctus

- Microakodontomys transitorius

- Chiroderma trinitatum

- Diclidurus albus

- Calomys callosus

- Monodelphis kunsi

- Euphractus sexcinctus

- Cerdocyon thous

- Coendou prehensilis

- Saccopteryx leptura

- Sturnira tildae

- Cerradomys scotti

- Gardnerycteris crenulatum

- Chiroderma villosum

- Chiroderma doriae

- Nectomys rattus

- Bradypus variegatus

- Dasypus novemcinctus

- Tamandua tetradactyla

- Herpailurus yagouaroundi

- Inia geoffrensis

- Gracilinanus agilis

- Proechimys roberti

- Puma concolor

- Uroderma magnirostrum

- Procyon cancrivorus

- Marmosops bishopi

- Leopardus guttulus

- Leopardus tigrinus

- Galictis cuja

- Sturnira lilium

- Thrichomys apereoides

- Eira barbara

- Dermanura cinerea

- Oligoryzomys rupestris

- Hylaeamys megacephalus

- Priodontes maximus

- Philander opossum

- Noctilio leporinus

- Micronycteris minuta

- Caluromys lanatus

- Anoura geoffroyi

- Lycalopex vetulus

- Molossus rufus

- Myotis nigricans

- Didelphis albiventris

- Calomys expulsus

- Anoura caudifer

- Lasiurus blossevillii

- Noctilio albiventris

- Cabassous tatouay

- Histiotus velatus

- Promops nasutus

- Speothos venaticus

- Nyctinomops aurispinosus

- Tapirus terrestris

- Eptesicus furinalis

- Cynomops abrasus

- Carollia perspicillata

- Mazama gouazoubira

- Holochilus sciureus

- Oligoryzomys stramineus

- Mazama americana

- Cuniculus paca

- Dermanura gnoma

- Artibeus lituratus

- Artibeus obscurus

- Blastocerus dichotomus

- Chironectes minimus

- Dasyprocta leporina

- Eumops auripendulus

- Dasypus septemcinctus

- Desmodus rotundus

- Eptesicus brasiliensis

- Eumops perotis

- Furipterus horrens

- Marmosa murina

- Leopardus pardalis

- Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris

- Lonchorhina aurita

- Lontra longicaudis

- Cynomops planirostris

- Platyrrhinus brachycephalus

- Micronycteris megalotis

- Molossops mattogrossensis

- Molossus molossus

- Myotis albescens

- Trachops cirrhosus

- Phyllostomus elongatus

- Phyllostomus hastatus

- Carterodon sulcidens

- Akodon lindberghi

- Oecomys cleberi

- Calomys tener

- Peropteryx macrotis

- Tayassu pecari

- Uroderma bilobatum

- Monodelphis americana

- Diphylla ecaudata

- Molossops temminckii

- Necromys lasiurus

- Glossophaga soricina

- Chrysocyon brachyurus

- Tapirus terrestris

- Mimon bennettii

- Myotis riparius

- Leopardus wiedii

- Monodelphis domestica

- Sciurus aestuans

- Lonchophylla dekeyseri

- Clyomys laticeps

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Cerrado biodiversity hotspot is characterized by a pronounced dry season and its unique array of drought- and fire-adapted plant species. As one of the largest producers of livestock and agricultural products on earth, Cerrado accounts for 30 percent of Brazil’s gross domestic product and supports millions who live dependent on the natural resources. The hotspot also harbors and stores significant amounts of water and carbon. [2]

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~12,000 |

>33% |

- pequi (

Caryocar brasiliense

), culturally and economically important fruit tree,

|

|

Birds |

>850 |

30 |

- Critically Endangered Brazilian merganser (

Mergus octosetaceus

)

[4]

, blue-eyed ground dove (

Columbina cyanopis

), considered extinct since 1941 until spotted again in 2015

[5]

,

|

|

Mammals |

|

|

- Vulnerable

[7]

giant armadillo (

Priodontes maximus

)

|

|

Reptiles |

262 |

~100 |

|

|

Amphibians |

>200 |

72 |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

~800 |

DD |

- represents 27 percent of all fish in South America |

|

Invertebrates |

DD |

DD |

- rich in butterflies, moths, termites, social wasps, and bees |

As one of the planet’s leading regions for agricultural and livestock production, Cerrado has clearing of land for pasture and monocultures as the major cause of habitat degradation. Vast areas of original vegetation cover are lost, and rapid advancement of deforestation continues to fragment the remains. Presently, the levels of deforestation and greenhouse gases emission in Cerrado are higher than that of the Amazon. Other main sources of threat include serious chemical pollution (Brazil uses the most pesticides amongst all the countries, with 19 percent of global use), damming, invasive species, GMOs, and artificially intensified fire regime.

[9]

Funding opportunities in Cerrado for conservation are currently limited. CEPF is investing 8 million US dollars in Brazil from 2016 to 2021, supporting the integration of sustainable production chains and creating incentives for sustainable business initiatives. The highest priorities reside in avoiding or minimizing new land clearing, restoring degraded lands, and expanding the network of protected areas. [10]

Cerrado Ecoregion

The Cerrado ecoregion is the largest savanna in South America and the biologically richest in the world. It encompasses central Brazil, northeastern Paraguay, and eastern Bolivia. Because of its location on the continent, the region shares borders with the largest South American biomes – the Amazon basin (to the north), Chaco and Pantanal (to the west), Caatinga (to the northeast), and Atlantic forests (to the east and south). Several major rivers have their headwaters in Cerrado. Savanna-like vegetation dominates the ecoregion, which grows on nutrient-poor, often deep and well-drained soils. Cerrado boasts at least 10,400 species of vascular plants, 780 of fishes, 180 of reptiles, 113 of amphibians, 837 of birds, and 195 of mammals. The levels of endemism vary, from 4 percent in birds to half in plants. By 1998, around 67 percent of the Cerrado ecoregion has been majorly modified or completely converted. Most of the large-scale modifications occurred in the last 50 years, with the construction of a new Brazilian capital (Brasília), highways, and the ever-expanding agricultural frontiers. Vast areas of soybeans, corn, and rice monocultures were established, which still pose as the primary threat to Cerrado biodiversity. [11] At present, 11 percent of the ecoregion is protected and have a 3.13 percent of terrestrial connectivity. [12]

Environmental History

The concept of Brasilia, an inland capital that would be protected from raids off the Atlantic coast, was first proposed in 1823 by independentist José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva, and the project was made official in the 1891 constitution of the Brazilian Republic. Though the idea was not forgotten, it only truly developed with president Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira, who created the Company of Urbanization of the New Capital and hired Oscar Niemeyer as an architect for many of the city’s buildings. Architect Lúcio Costa designed the “Plan piloto” (masterplan) for the city, which was to become a center for Brazil’s administration. Construction began in 1956, and Juscelino Kubitschek’s push to finish the city before the end of his term resulted in an influx of migrant workers from the rest of the country. Instead of leaving, however, these migrants, or “candangos,” settled outside of the main administrative complex, in villages which grew to become satellite cities. [13]

The proliferation and growth of satellite cities started with the construction of the city itself. Indeed, a settlement called Cidade Livre was permitted during the time of construction, but permanent housing was only planned for in the residential areas of the Pilot Plan, which was designed to house 600,000 people at most. The Cidade Livre, despite being advertised positively to attract workers, became a place of poverty and violence. [14]

At the turn of the millenia, the capital had grown 18 administrative units on top of the initial design. In fact, the administrative capital stands much smaller than its satellite cities Taguatinga and Ceilândia. In his writing, Richard J. Williams argues that as the city expands, the Pilot Plan will become little more than a translation of a historic district, as development will continue to occur independently from the original plan. [15] For reasons, Alain Bertaud agrees with Williams, suggesting that the capital’s central business district is poorly located, hindering proper development, and now differs greatly from the city’s center of gravity and its morphological center, which are both located further west. [16]

Today, the city is criticized by some, partly for lack of liveliness and of “city life” due to strict zoning. At the same time, the contrary is said of satellite cities, which lack structure to some extent. Additionally, the utopian vision of Brasilia as representing Brazil is somewhat hindered by the homogeneity of the wealthy population living in the main part of the city. [17]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

One of the environmental problems that continues to plague Brasilia today is the accumulation of sediments in lake Paranoá, a major source of drinking water for the city. Residential areas and continuous construction are the main contributors to this phenomenon, which would most easily be fixed with the restoration of dense forest cover in the watershed. [18] Additionally, the lake’s levels of microcystins, toxins produced by cyanobacteria algae that cause many unpleasant symptoms in humans, are considerably higher than recommended by the World Health Organization. [19]

Although Brasilia’s pollution problems are negligible compared Brazil’s other major cities, the capital’s rapid, unplanned growth left many of its satellite cities unserviced. Indeed, cities like Arapoanga do not have a sewage system. [20] Solid waste management is similarly unequal in the city, although it seems to be trying to improve the quality of services throughout the city.

Indeed, the city benefitted from a $100 million loan from the Inter-American Development Bank, $35 million of which are to be used to rehabilitate two composting plants and the construction or rehabilitation of seven solid waste separation plants. The project includes the expansion of the water supply network, the pavement of new roads and tree planting. [21]

The federal district is surrounded by a network of thin, yet well connected forest strips. On the east end of the Federal District, valleys are completely occupied by fields. West, south and closer to the city to the east, land use is much less regular, and some natural cover remains, interspersed with large towns, small settlements, and a few fields. Parks just north and south of the main city provide a large area of dense woodlands, and a vast stretch of natural cover remains north of the federal district, where dense forests occupy the valleys and mountain tops are somewhat more bare.

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

As of 2010, Brasilia had a population of 2.48 million. [23] Although the administrative center of the city has stayed quite intact in the past 30 years, the city has grown relentlessly, especially through the expansion its satellite cities. Thus, the federal district includes many urban clusters that are structured along rigid grid plans, sprawling outwards along roads, without control. Many areas that were covered in woodlands in the 1980s have been replaced by developments or fields. Older developments around the Paranoa lake, just east of the city center, have not changed since the 1980s and seem to be reserved for the wealthy portion of the population. Similarly pleasant neighborhoods have densified west of the center. Yet, further away from the administrative core, denser neighborhoods and satellite cities are sprawling onto natural vegetation, providing homes for lower-income households .

Governance

Brazil is divided in 26 states and one federal district, in which Brasilia is situated. The capital is one of the 29 administrative regions that compose the federal district. [24] Brasilia and most of its satellite cities fall under the control of government of the federal district, which is headed by the governor. [25] Some towns further out, however, are located beyond the limits of the federal district, and fall under the jurisdiction of the government of Goias.

City Policy/Planning

The federal district’s 2011 development plan is rather broad, listing objectives to guide its policymaking and listing initiatives but without specific targets or deadlines. The document includes a section on quality of life, whose fourth objective is to encourage urban development and zoning that takes sustainability and social justice into account to promote decent housing. The ninth objective is to guaranty environmental quality in the federal district. Aside from these two points, the plan makes little to no mention of sprawl or biodiversity. However, the district did fulfill its commitment to provide adequate zoning. [27]

Indeed, the latest zoning plan of the federal district, or Plano Diretor de Ordenamento Territorial do Distrito Federal , was written in 2009 and updated in 2012. [28] The plan includes Brasilia and all of its satellite cities that fall within the borders of the district, dividing the area’s “urban macrozone” into multiple zones, which it maps in detail. The document even shows urban expansion zones, which, aside from a large patch south of the capital, mostly fills in the gaps of the existing city, pushing towards a slightly more compact form of development. [29] The plan also has a section concerning the district’s natural areas, including green corridors to ensure that these areas are well connected.

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Brazil submitted the most recent version of its NBSAP (V3) in 2016, and updated it in February 2018 to include new actions that are multi-sectoral in scope. The national action plan only mentions urbanization as a threat to biodiversity in passing and does not focus its actions on mitigating conflict between biodiversity and urbanization. [34]

National

Brazil leads many initiatives to protect its biodiversity. The Brazilian Alliance for Zero Extinction (BAZE) was created in 2006, and went on to publish a map of BAZE sites—areas that contain critically endangered and endemic species. [35] The Cerrado contains 26 BAZE sites, including two near the federal district: Ribeirão Santana, which contains Simpsonichthys santanae , and Lagoa Perta-pé, which contains Pamphorichthys pertapeh . [36] In terms of information management, Brazil has developed a central portal for biodiversity, and already has many various databases on flora and fauna such as Biodiversity Flora 2020. [37]

The Ministry of the Environment (MMA) leads operations to combat desertification and climate change, and its Secretariat of Biodiversity (SBio) is responsible for conservation efforts throughout the country. [38] SBio also acts to protect ecological corridors through its Ecological Corridors Project , and is striving to preserve them throughout Brazil. [39] SBio has a critical role in implementing the NBSAP, through four priority agendas, including the conservation of threatened species, of protected areas, and of ecosystems through the promotion of sustainable landscape management, and monitors the greenhouse gas emissions. [40]

Regional

The National Center for Biodiversity Assessment and Research and Conservation of Cerrado was created by the Ministry of Environment's Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation in 2017. Throughout the ecoregion, among other initiatives, the organization works to assess the state of fauna, to conserve species and ecosystems, to conduct plant and insects monitoring programs, and to provide support for in-situ conservation efforts. [41]

Local

On a local level, the Federal District has its own Secretary of State for the Environment which takes care of conservation and environmental education. The Secretary manages the city’s botanical gardens, oversees water supply management and waste management. [42]

Protected Areas

Brasilia is surrounded by protected areas, including two level Ia reserves— the 45km2 botanical gardens and the 96km2 Estação Ecológica De Águas Emendadas (Watershed Ecological Station)— and one level II reserve, the 424km2 Brasilia National Park. Although the federal district has many other protected areas, it is unclear whether their protection is actually enforced. The two level-IV areas are the 4.8km2 Arie Santuário De Vida Silvestre Do Riacho Fundo and the 11km2 Arie Da Granja Do Ipê . Finally, the three level-V areas in the district are the 237km2 Área De Proteção Ambiental Da Bacia Dos Ribeirões Do Gama E Cabeça De Veado , the 418km2 Área De Proteção Ambiental Da Bacia Do Rio Descoberto , and the 5,000km2 Área De Proteção Ambiental Do Planalto Central , which covers most of the district.

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) operates in the cerrado, northeast of the federal district. T h e organization’s main work consists in influencing policymaking, minimizing land clearing , restoring degraded lands, promoting good agricultural practices and sustainable resource use, supporting the expansion of protected areas and the protection of threatened species, and improving the existing monitoring system. The CEPF has a full report that explains the organization’s current and future strategies for the Cerrado. When discussing the threats to biodiversity in the ecoregion, the report also underlines the potential of natural regeneration of degraded land, which occurs rather rapidly with the type of flora that grows in the ecoregion. [43]

The Nature conservancy also works in the Cerrado, but far, South West of Brasilia. T h e organization collaborates with local NGOs, farmers, agribusiness companies, and governmental institutions to promote a combined use of sustainable ranching or farming with land protection surrounding Emas National Park. The main objective of the initiative is protect habitats while improving soil and water quality and profitability. [44]

On a more political level, WWF and Greenpeace worked to write a manifesto to write a manifest in 2017, to protect the Cerrado. The document was recently adopted by a major agribusiness company that has committed to stop deforestation in the area. [45]

More locally, Bem Diverso is an organization that hosts some biodiversity events in the capital, in cooperation with the UNDP. Indeed, although none of the organization’s six “Citizen Territories” are located near the federal district, it organizes an Annual Meeting in Brasilia to raise awareness and promote cooperation between organizations like the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation , the UNDP and the Global Environment Fund. [46]

Conclusion

Despite the rapidity of growth in Brasilia, the city seems to be planning to accomodate more people and f or malize existing developments, even if such planning is somewhat controversial for favoring high-end developments. The proposed expansion zones mostly occur within gaps of the current city. However, urban expansion does not seem to be of any explicit concern to the local government. In fact, the rate of construction itself constitutes a major problem for the city’s water supply.

High-status protected areas in the federal district seem to be enforced properly, providing very dense, natural forest cover. Yet, non-forest natural vegetation is also a key component of the ecoregion, and should be valued as such. Additionally, lower-status protected areas do not seem to be truly protected, and rather contain land uses of various types, including residential areas and agriculture.

Therefore, some conservation priorities of Brasilia should be to limit land conversions and deforestation, to integrate the reduction of sprawl into its development and zoning plans, and to increase its true protected area to include various cover types.

[1] World Wildlife Fund, “Central South America: Central Brazil, into Bolivia and Paraguay,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0704 (accessed August 7, 2018).

[2] CEPF. “Cerrado.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cerrado.

[3] CEPF. “Cerrado - Species.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cerrado/species.

[4] “Mergus Octosetaceus (Brazilian Merganser).” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22680482/123509847.

[5] BirdLife International. “Back from the Dead? The Story of the Blue-Eyed Ground-Dove.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.birdlife.org/worldwide/news/back-dead-story-blue-eyed-ground-dove.

[6] “Brasilia Tapaculo.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en .

[7] “Giant Armadillo.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en .

[8] “Giant Anteater.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en .

[9] CEPF. “Cerrado - Threats.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cerrado/threats.

[10] CEPF. “Cerrado.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cerrado.

[11] WWF. “Central South America: Central Brazil, into Bolivia and Paraguay | Ecoregions.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0704.

[12] “Cerrado.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed July 26, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60704.

[13] About Brasilia & Brazil, “History of Brasilia,” http://www.aboutbrasilia.com/facts/history.php (accessed August 7, 2018).

Building the World, “The Founding of Brasilia, Brazil,” http://blogs.umb.edu/buildingtheworld/founding-of-new-cities/the-founding-of-brasilia-brazil/ (accessed August 7, 2018).

[14] Richard J. Williams, “Brasília after Brasília,” Progress in Planning 67, 4 (May 2007), 301-366.

[15] Richard J. Williams, “Brasília after Brasília,” Progress in Planning 67, 4 (May 2007), 301-366.

[16] Alain Bertaud, “Brasilia spatial structure: Between the Cult of Design and Markets,” International Seminar, Metropolitana Brasilia 2050: Preservation and Development (2010)

[17] Robin Banerji, “Niemeyer’s Brasilia: Does it work as a city?,” BBC (Decemebr 7, 2012), https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20632277.

https://www.ft.com/content/52a967d0-409d-11e2-8f90-00144feabdc0

[18] C. Franz et al., “Sediments in urban river basins: Identification of sediment sources within the Lago Paranoá catchment, Brasilia DF, Brazil – using the fingerprint approach,” Science of the Total Environment 466-467 (2014), 513-523.

[19] United States Environemntal Protection Agency, “Microcystins,” https://iaspub.epa.gov/tdb/pages/contaminant/contaminantOverview.do?contaminantId=-1336577584 (accessed August 7, 2018).

N. B. Oliveira et al., “Bioacumulation of Cyanotoxins in Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Silver Carp) in Paranoá Lake, Brasilia-DF, Brazil,” Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 90, 3 (2013), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00128-012-0873-7.

Melissa Breyer, “What is microcystin?” Mother Nature Network (August 4, 2014), https://www.mnn.com/family/protection-safety/stories/what-is-microcystin.

[20] Ana Niclaci da Costa, “50 years on, Brazil's utopian capital faces reality,” Reuters (April 21, 2010), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-brasilia/50-years-on-brazils-utopian-capital-faces-reality-idUSTRE63K4CT20100421.

[21] “Brasilia to improve solid waste management, urban environmental quality with IDB support,” IDB News (Novemeber 3, 2016), https://www.iadb.org/en/news/news-releases/2016-11-03/solid-waste-management-and-urban-environment-in-brazil%2C11630.html.

[22] CodePlan, Secretaria de Estado de Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão, & Governo do Distrito Federal, “Atlas do Distrito Federal,” 2017.

[23] City Population, “Brasilia,” https://www.citypopulation.de/php/brazil-distritofederal.php?cityid=530010805 (accessed August 7, 2018).

[24] Amelia Meyer, Brazil, “Distrito Federal,” 2010, https://www.brazil.org.za/distrito-federal.html.

[25] Governo do Distrito Federal, “Sobre o Governo,” http://www.df.gov.br/category/sobre-o-governo/ (accessed August 7, 2018).

[26] Maps of World, “Administrative Regions of Federal District,” https://www.mapsofworld.com/brazil/state/distrito-federal/administrative-regions.html (accessed August 7, 2018).

[27] Governo do Distrito Federal, “Plano Estratégico do Governo do Distrito Federal” (December 2011).

[28] “LC no 854, Plano Diretor de Ordenamento Territorial do Distrito Federal – PDOT” Diário Oficial do Distrito Federal (October 17, 2012).

“LC no 803, Plano Diretor de Ordenamento Territorial do Distrito Federal – PDOT”, Câmara Legislativa do Distrito Federal (April 25, 2009).

[29] “LC no 854, Plano Diretor de Ordenamento Territorial do Distrito Federal – PDOT” Diário Oficial do Distrito Federal (October 17, 2012).

[30] “LC no 854, Plano Diretor de Ordenamento Territorial do Distrito Federal – PDOT” Diário Oficial do Distrito Federal (October 17, 2012), 6.

[31] “LC no 854, Plano Diretor de Ordenamento Territorial do Distrito Federal – PDOT” Diário Oficial do Distrito Federal (October 17, 2012), 9.

[32] Leon Kaye, “Making Brasília a model green city,” The Guardian (October 10, 2011).

“O Setor Noroeste em Brasília, os índios, os mitos e os fatos,” Política & Economia (Ocotber 26, 2011), https://www.politicaeconomia.com/2011/10/o-setor-noroeste-em-brasilia-os-indios.html.

[33] Callison RTKL, “Brasilia 2 Master Plan Phase 2” https://www.callisonrtkl.com/projects/brasilia-2-master-plan-phase-2/?utm_source=rtkl_com&utm_medium=redirect&utm_term=/projects/brasilia-2-master-plan-phase-2/&utm_campaign=site_launch_2016#sthash.7hDq8Qbg.xptt (accessed August 7, 2018).

[34] Ministry of the Environment, Secretariat of Biodiversity. NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN. Pdf file. Accessed on August 16, 2019. https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/br/br-nbsap-v3-en.pdf .

[35] Ministry of the Environment, Secretariat of Biodiversity, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan” (2016), 32.

[36] Alliance for Zero Extinction, “Brazilian Alliance for Extinction Zero (BAZE) Conservation Strategy,” http://zeroextinction.org/case-studies/the-brazilian-alliance-for-extinction-zero-baze-conservation-strategy/ (accessed August 7, 2018).

[37] PortalBio, “Biodiversity Portal,” https://portaldabiodiversidade.icmbio.gov .br/ (accessed August 7, 2018).

[38] Ministério do Meio Ambiente, “Secretaria de Biodiversidade (SBio),” http://www.mma.gov.br/informma/item/8724-secretaria-de-biodiversidade-e-florestas (accessed August 7, 2018).

Ministério do Meio Ambiente, “Programas do MMA,” http://www.mma.gov.br/programas-mma (accessed August 7, 2018).

Ministério do Meio Ambiente, “Gestão Territorial,” http://www.mma.gov.br/gestao-territorial (accessed August 7, 2018).

[39] Ministry of the Environment, Secretariat of Biodiversity, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan” (2016), 46.

[40] Ministry of the Environment, Secretariat of Biodiversity, “National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan” (2016), 115.

[41] CBC ICMBio-MMA, “CBC,” http://www.icmbio.gov.br/cbc/ (accessed August 7, 2018).

[42] Secretaria de Estado do Meio Ambiente do Distrito Federal, “Sema em Ação,” http://www.sema.df.gov.br/, (accessed August 7, 2018).

Jardim Botânico de Brasília, Conheça o Jardim Botânico de Brasília, http://www.jardimbotanico.df.gov.br/ (accessed August 7, 2018).

[43] Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Cerrado - Priorities,” https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cerrado/priorities (accessed August 7, 2018).

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Ecosystem Profile, Cerrado Biodiversity Hotspot” (February 2017).

[44] The Nature Conservancy, “Brazil, Cerrado,” https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/latinamerica/brazil/placesweprotect/cerrado.xml (accessed August 7, 2018).

[45] World Wildlife Fund, “Environmentalists ask markets to help stop the destruction of the Cerrado” (September 11, 2017), http://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/press_releases/?310899/Environmentalists-ask-markets-to-help-stop-the-destruction-of-the-Cerrado.

World Wildlife Fund, “Saving the Cerrado, Brazil’s vital savanna” (January 25, 2018), https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/saving-the-cerrado-brazil-s-vital-savanna.

[46] ONU Brazil, “PNUD e parceiros promovem em Brasília evento sobre uso sustentável da biodiversidade” (December 5, 2017), https://nacoesunidas.org/pnud-e-parceiros-promovem-em-brasilia-evento-sobre-uso-sustentavel-da-biodiversidade/

Projecto Bem Diverso, “Territórios,” http://www.bemdiverso.org.br/territ%C3%B3rios (accessed August 7, 2018).