Cape Town, South Africa

- Global Location plan: 32.92oS, 42oE

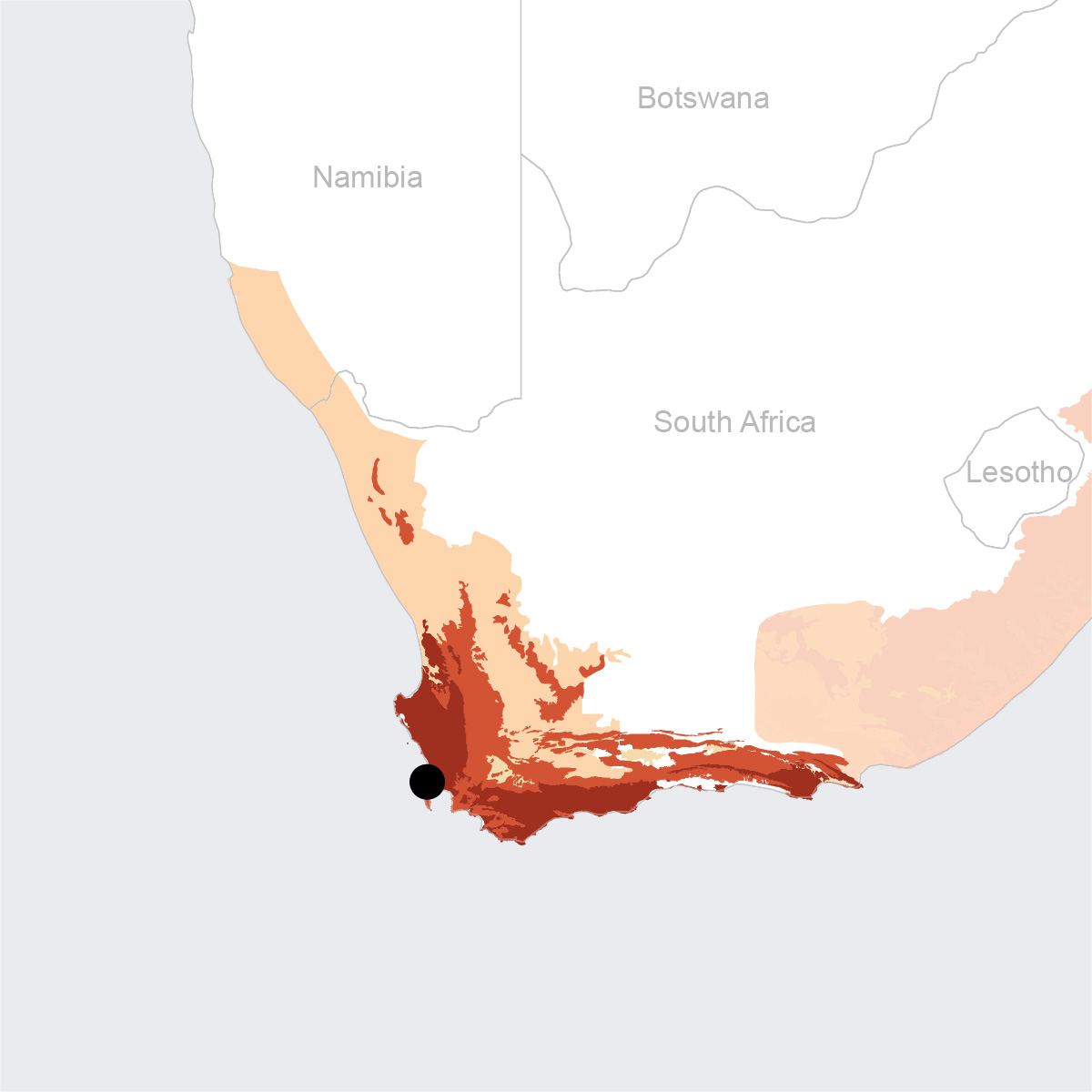

- Hotspot: Cape Floristic Province

- Population 2016: 3,660,000

- Projected population 2030: 4,322,000

- Mascot Species:

- Plants: king protea (Protea cynaroides)

- Birds: Cape sugarbird (Promerops cafer), orange-breasted sunbird (Nectarinia violacea), the Protea canary (Serinus leucopterus) and the Cape siskin (Serinus totta)

- Mammals: bontebok (Damaliscus dorcas dorcas) antelope, Cape grysbok (Raphicerus melanotis), Fynbos golden mole (Amblysomus corriae), Endangered Van Zyl's golden mole (Cryptochloris zyli)

- Reptiles: Critically Endangered geometric tortoise (Psammobates geometricus)

- Amphibians: Critically Endangered Table Mountain ghost frog (Heleophryne rosei), Critically Endangered micro frog (Microbatrachella capensis), montane marsh frog (Poyntonia paludicola)[1]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Strongylopus fasciatus

- Breviceps rosei

- Capensibufo magistratus

- Capensibufo selenophos

- Arthroleptella rugosa

- Poyntonia paludicola

- Strongylopus bonaespei

- Capensibufo tradouwi

- Sclerophrys pantherina

- Arthroleptella bicolor

- Arthroleptella drewesii

- Cacosternum karooicum

- Strongylopus grayii

- Tomopterna delalandii

- Cacosternum australis

- Capensibufo rosei

- Capensibufo deceptus

- Amietia fuscigula

- Xenopus laevis

- Amietia delalandii

- Cacosternum capense

- Cacosternum capense

- Arthroleptella lightfooti

- Arthroleptella villiersi

- Breviceps gibbosus

- Vandijkophrynus gariepensis

- Cacosternum capense

- Heleophryne rosei

- Microbatrachella capensis

- Tomopterna tandyi

- Arthroleptella subvoce

- Sclerophrys pantherina

- Sclerophrys pantherina

- Amietia poyntoni

- Hyperolius horstockii

- Vandijkophrynus angusticeps

- Heleophryne orientalis

- Hyperolius marmoratus

- Semnodactylus wealii

- Xenopus gilli

- Sclerophrys capensis

- Breviceps acutirostris

- Breviceps fuscus

- Breviceps montanus

- Breviceps namaquensis

- Arthroleptella landdrosia

- Amietia vandijki

- Cacosternum platys

- Cacosternum nanum

- Microbatrachella capensis

- Heleophryne purcelli

- Cacosternum aggestum

Mammals

- Tasmacetus shepherdi

- Damaliscus pygargus

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Mesoplodon grayi

- Mesoplodon hectori

- Mesoplodon layardii

- Miniopterus fraterculus

- Myosorex longicaudatus

- Otomys unisulcatus

- Petromyscus collinus

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Rhinolophus clivosus

- Herpestes ichneumon

- Chrysochloris asiatica

- Cynictis penicillata

- Atilax paludinosus

- Mellivora capensis

- Sauromys petrophilus

- Tragelaphus oryx

- Otocyon megalotis

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Mastomys coucha

- Felis silvestris

- Proteles cristata

- Tursiops truncatus

- Panthera pardus

- Tursiops aduncus

- Equus zebra

- Otomys sloggetti

- Steatomys krebsii

- Diceros bicornis

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Leptailurus serval

- Panthera pardus

- Papio ursinus

- Herpestes pulverulentus

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Equus zebra

- Chlorocebus pygerythrus

- Chlorocebus pygerythrus ssp. pygerythrus

- Lagenorhynchus obscurus

- Dendromus melanotis

- Mus minutoides

- Mus musculus

- Otomys irroratus

- Syncerus caffer

- Grampus griseus

- Caracal caracal

- Rousettus aegyptiacus

- Otomys laminatus

- Graphiurus ocularis

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Orcinus orca

- Genetta tigrina

- Parahyaena brunnea

- Gerbillurus paeba

- Hyperoodon planifrons

- Rhinolophus capensis

- Rhabdomys pumilio

- Orycteropus afer

- Berardius arnuxii

- Ictonyx striatus

- Poecilogale albinucha

- Crocidura flavescens

- Canis mesomelas

- Chrysochloris asiatica

- Elephantulus edwardii

- Elephantulus rupestris

- Mesoplodon mirus

- Delphinus delphis

- Saccostomus campestris

- Tragelaphus scriptus

- Lagenodelphis hosei

- Cistugo lesueuri

- Macroscelides proboscideus

- Hystrix africaeaustralis

- Dasymys incomtus

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Miniopterus natalensis

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Lepus saxatilis

- Delphinus capensis

- Eubalaena australis

- Lissodelphis peronii

- Lepus capensis

- Desmodillus auricularis

- Sylvicapra grimmia

- Myosorex varius

- Genetta genetta

- Procavia capensis

- Amblysomus corriae

- Pronolagus saundersiae

- Rattus rattus

- Suncus varilla

- Ceratotherium simum

- Sousa plumbea

- Neoromicia nana

- Tadarida aegyptiaca

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Kogia sima

- Myomyscus verreauxii

- Arctocephalus pusillus

- Micaelamys namaquensis

- Aonyx capensis

- Caperea marginata

- Dendromus mesomelas

- Suricata suricatta

- Feresa attenuata

- Georychus capensis

- Graphiurus murinus

- Malacothrix typica

- Cryptomys hottentotus

- Myotis tricolor

- Mystromys albicaudatus

- Raphicerus campestris

- Raphicerus melanotis

- Nycteris thebaica

- Oreotragus oreotragus

- Parotomys brantsii

- Pelea capreolus

- Alcelaphus buselaphus

- Otomys karoensis

- Acomys subspinosus

- Micaelamys granti

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Balaenoptera physalus

- Bathyergus suillus

- Felis nigripes

- Bunolagus monticularis

- Globicephala melas

- Kogia breviceps

- Crocidura cyanea

- Gerbilliscus afra

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Eremitalpa granti

- Cephalorhynchus heavisidii

- Eptesicus hottentotus

- Vulpes chama

- Neoromicia capensis

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Cape Floristic Province Hotspot lies entirely within the borders of South Africa [2] , and is one of the five Mediterranean-type systems. [3] Landscape in the hotspot is now dominated by fynbos (Afrikaans for “fine bush”), a heathland comprising hard-leafed, evergreen, and fire-prone shrubs. Apart from fynbos, Renosterveld (Afrikaans for “rhinoceros’ veld”) is the other most extensive vegetation type. [4] The Cape Floristic Province is the only hotspot that encompasses an entire floral kingdom. In fact, this small area contains nearly 3% of the world’s plant species on only 0.05% of total land area. [5]

Species statistics [6]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~9,000 |

69% |

- king protea ( Protea cynaroides ), South Africa's national flower |

|

Birds |

~320 |

6 |

- Cape sugarbird ( Promerops cafer) [7] , orange-breasted sunbird ( Nectarinia violacea ) [8] , and Cape siskin ( Serinus totta ) [9] |

|

Mammals |

~90 |

4 |

- Vulnerable mountain zebra ( Equus zebra ) [10] |

|

Reptiles |

~100 |

~25% |

- the highest tortoise diversity on Earth - the Critically Endangered geometric tortoise ( Psammobates geometricus ) |

|

Amphibians |

>40 |

16 |

- 44 types of frogs (>55% endemic) |

|

Freshwater Fishes |

~35 |

>12 |

|

|

Invertebrates |

DD |

DD |

- more than 230 types of butterflies (30% endemic) |

Unfortunately, the hotspot also has the highest concentration of Threatened plants; 1,406 species are on the IUCN’s Red List of Endangered plants and nearly 300 are on the brink of extinction. 29 are already extinct in the wild. [11] It has been determined that many localized fynbos endemics persist in patches of only 4-15 hectares. Restricted ranges are another characteristic feature of the hotspot, with the complete range of some species being smaller than half of a soccer field. Plowing a building or a small piece of land in this hotspot can decimate the entire world population of a unique life form. [12]

The greatest threat to biodiversity in the Cape Floristic Province is agricultural and urban expansion. Agricultural land conversion has already consumed 26% of the hotspot and especially the lowland areas – 9% of renosterveld and 49% of fynbos habitats have been destructed [13] and only 0.6% and 4.5% respectively are protected. [14] Even though poor soils and steep slopes in the mountains limit agriculture, the industries of wine, olive, rooibos tea, honeybush tea, and ornamental flower cultivation (mainly proteas) are rapidly expanding. According to projections, an additional 15 to 30 percent of remaining habitats will be converted to farmland within the next 20 years. [15] Less than 1% of the hotspot is under national protection, and 95% of protected areas are mountainous, leaving lowland habitats particularly vulnerable to human settlement encroachment. [16] Roughly 5 million people live in the hotspot, of which 3 million are concentrated in Cape Town. The estimated 2% growth rate for the city poses a serious threat to the lowlands nearby. Another significant source of threat comes from the invasion of alien species. Nearly 70 percent of land is covered by low-density or scattered patches of invasive species. Conservation efforts in the Cape Floristic Province are institutionally constrained due to lack of capacity in management, legal rights, and also insufficient public involvement. About 80 percent of the hotspot’s land is privately owned, making conservation largely dependent on land use regulation enforcement. [17] The viticulture and flower industries have shown little interest in partnering with conservation efforts. [18] CEPF invested 7.65 million US dollars in the hotspot from 2001 to 2011, focusing on enhancing civil society involvement, establishing small grants, and promoting innovative private sectors. [19]

Lowland Fynbos and Renosterveld

The Lowland Fynbos and Renosterveld ecoregion, located at the southwestern tip of the African continent, is a fire-prone ecosystem featuring predominantly winter rainfall (between 300 and 750 mm annually). The ecoregion encompasses most of the heavily transformed lowland portion of the Cape Floristic Province hotspot. The infertile, sandy soils support a great diversification of plant taxa with high levels of endemism amongst reptiles, amphibians, insects, and freshwater fishes. The two dominant types of landscape – fynbos and renosterveld, occupy about the same percentage of land, and are characterized by small-leafed, evergreen shrubs. Fynbos is noted by four major plant types; amongst which the rush or reed-like restioid is uniquely diagnostic. On the other hand, renosterveld lacks restioid. This vegetation type comprises a low shrub layer up to 2 m tall, composed mainly of ericoid and renosterbo. [20]

The lowland and montane fynbos and renosterveld ecoregions together harbor approximately 7,000 of the 9,000 species within the Cape Floristic Province region. About 80 percent of the species in the ecoregion is endemic. Particularly, a large number of these are point endemics, restricted to areas of 100 square kilometers or less. Another noteworthy phenomenon is the plant adaptations to fire and the widespread occurrence of myrmecochory (i.e. seed dispersal by ants). There are five major perennial river systems in the region, serving as important habitats for locally endemic freshwater fishes and migratory routes for flora and fauna. A flagship mammal is the bontebok ( Damaliscus dorcas dorcas ), which is now mainly found in protected sanctuaries. [21]

The Lowland fynbos and renosterveld ecoregion has been severely impacted by agriculture, invasive alien plants, and urbanization. About 41 percent of the original fynbos and 75 percent of renosterveld have been transformed, mostly to farmlands. Novel forms of agriculture, such as the cultivation of cut flowers, beverages and medicinal plants, are encroaching on otherwise marginal lands. Urbanization is especially serious surrounding the two metropolitan centers – Cape Town in the west and Nelson Mandela in the east – and along the coastal areas. [22] At present, there are around three dozens of protected areas in the ecoregion – the largest one being the West Coast National Park. The ecoregion is only 5% protected, which possesses a mere 2.18% of terrestrial connectivity. [23]

Environmental History

As a result of climate changes about 15 million years ago, rain forests were replaced by flammable sclerophyll , and periodic burns became an integral ecosystem process. Landscape in the hotspot is nowadays dominated by fynbos (Afrikaans for “fine bush”), a heathland comprising hard-leafed, evergreen, and fire-prone shrubs. Apart from fynbos, Renosterveld (Afrikaans for “rhinoceros’ veld”) is the other most extensive vegetation type. [24]

The Cape has been an attractive place for humans for more than 21,000 years. It offered perennial water, abundant wildlife and a relatively sheltered environment. The area was first inhabited by San hunter gatherers and eventually by Khoi herders (since about 2000 years ago).

The city’s population has had a few dramatic periods of growth: in the late 19th century, and in the period following World War II. The post-Apartheid period saw a surge in urbanization across the country. This surge aligned with a hope that the repeal of apatheid spatial segregation laws would lead to a significant spatial reconfiguration away, but a lack of aimed at integration and desegregation did not support this tradition, and the city continued to grow in an unequal and segregated form.

Thus far the city’s planning policies have not effectively restrained the sprawling, low density, single-family form of urbanization that is dominant across middle and high income developments.

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

“The highly transformed Cape Flats area outside Cape Town, has the highest concentration of Red Data species in the world and is the leading site for metropolitan species extinctions globally, with fifteen species per km2 being in danger of extinction.” [25]

Cape Town’s water demand has long threatened to outstrip its water supply. In 2018, the water crisis came to a dramatic head as the city was just days away from running out municipal water supplies as an intensive rain storm broke as brutal drought in 2018. Capetonian’s aggressive water conservation efforts are also credited in averting the worst case scenario, which the city dubbed “day zero.” [26] Ecological damage has also undermined the city’s access to water; upriver sections have been cut off from their waterways by unplanned urbanization, and down river sections have become severely polluted. [27]

The city has a range of vulnerabilities to natural hazards: [28]

- Flooding of sand dune areas

- Summer wildfires are especially dangerous due to strong seasonal winds

- Human-wildlife conflict (especially with baboons)

- Storm surge and sea level rise

Urbanization over the past 350 years has significantly eroded biodiversity in the region. Eleven of 21 nationally recognized critically endangered vegetation types occur in the city. [29] Most urban development has taken place on biodiversity rich lowlands which has put especially high pressure on these areas.

Poverty, unemployment, and housing shortfalls tend to pit low income communities against biodiverse habitats. Illegal settlements continue to expand into fragile ecosystems as the population grows. Illegal harvesting of biodiversity resources also plays an important role in the informal economy. Wilderness areas are sometimes viewed as unsafe spaces due to the high crime rate in the city. [30] The biodiversity in Cape Town is confined to so few remnant patches that have so many rare species (some of which only occur at one or a few remnant sites), that the protection of these patches is critical. This kind of protection is challenging to facilitate due to cultural resistance to densification, the lack of government funds to purchase lands for conservation, and the limited capacity to monitor these patches and prevent disturbance. The lowland areas are most highly contested. [31]

Informal settlements areas on dunes are located on unstable, shifting ground, and are vulnerable to flooding; these dune areas were flattened with heavy machinery during apartheid for low-income housing, thereby bulldozing extensive areas of the Cape Flates Dune Strandveld vegeatation and wetlands and relegating housing for the poor to vulnerable areas. This and other aspects of the city’s aparthied legacy have led to very unequal access to conservation areas and exposure to environmental hazards, with poor black communities generally lacking access and being subject to high exposure. In light of the heavy lingering effects of apartheid planning, the CEPF Hotspot Profile authors suggest that despite there being “a desire to meet commitments to international conventions, the pressing need to redress past inequalities in South Africa has diminished the relative emphasis on conservation at all levels of government” [32]

Another challenge to preserving biodiversity in the face of urban growth is that many species native species are adapted to and require frequent fires to thrive. Invasive species, especially plant species are also a problem as they both aggressively outcompete indigenous species and often use more water. [33]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

South Africa’s second NBSAP, built on the outcomes of the first (2005) and the second National Biodiversity Assessment (2011), was released in 2015. This latest version includes six strategic objectives, summarized as - 1) enhance the management of biodiversity assets and contribution. 2) enhance resilience through investments in ecological infrastructure. 3) mainstream biodiversity. 4) mobilize the public. 5) develop an equitable and suitably skilled workforce. 6) support effective knowledge foundations, including indigenous knowledge and citizen science. [36] The Plan doesn’t specifically identify population growth as one of the major threats to biodiversity, but mentions urban and coastal development posing pressure to corresponding ecosystems. [37]

The Cape Action Plan for the Environment (CAPE) was the result of a comprehensive planning and strategy development process conducted between 1998 and 2000 that involved stakeholders from government, academia, NGOs, and local communities. This planning process included the development of a spatial plan of priorities to identify areas for a conservation area network at the scale of 1:250,000 for achieving conservation targets for Broad Habitat Units. The goals of the action plan were to:

- “establish an effective reserve network, enhance off-reserve conservation, and support bioregional planning”

- “strengthen and enhance institutions, policies, laws, cooperative governance, and community participation”

- “develop methods to ensure sustainable yields, promote compliance with laws, integrate biodiversity concerns into catchment management, and promote sustainable ecotourism” [38]

The ministries that signed a memorandum of understanding intended to facilitate the implementation of CAPE included the Ministry of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, the Ministry of Water Affairs and Forestry, and the Eastern Cape and Western Cape provincial governments. [39]

Other important plans, reports, and action strategies include:

- City of Cape Town Bioregional Plan

- 2012: Biodiversity network: Methods and results (Technical C-plan & Marxan analysis) [40]

- 2009: Strategic plan 2009-2019. [41]

- 2011: Moving mountains: Cape Town’s action plan for energy and climate change. [42]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

- Funds & Trusts

- TNC Water Fund

- Table Mountain Fund

- The Green Trust

-

International NGOs

- Flora and Fauna International

- Conservation International

- BirdLife International

-

National NGOs

- WWF – South Africa

- Botanical Society of South Africa

- Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa

- BirdLife South Africa and the Cape Bird Club

-

Private Sector + Community Groups

- Fynbos Forum

- Western Conservation Association

- Fynbos Ecotourism Foru

[1] “Cape Floristic Region: Species,” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cape-floristic-region/species, (Accessed March 19, 2019).

[2] CEPF. “Cape Floristic Region.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cape-floristic-region.

[3] “Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p 7.

[4] CEPF. “Cape Floristic Region.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cape-floristic-region.

[5] “Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p 7.

[6] CEPF. “Cape Floristic Region - Species.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cape-floristic-region/species.

[7] “Cape Sugarbird (Promerops Cafer) - BirdLife Species Factsheet.” BirdLife International. Accessed June 14, 2019. http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/22717447.

[8] “Orange-Breasted Sunbird (Anthobaphes Violacea) - BirdLife Species Factsheet.” BirdLife International. Accessed June 14, 2019. http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/orange-breasted-sunbird-anthobaphes-violacea.

[9] “Cape Siskin (Crithagra Totta) - BirdLife Species Factsheet.” BirdLife International. Accessed June 14, 2019. http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/Cape-Siskin.

[10] “Mountain Zebra.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[11] “Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p 9-10.

[12] “Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p 8.

[13] CEPF. “Cape Floristic Region - Threats.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cape-floristic-region/threats.

[14] Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p 10.

[15] CEPF. “Cape Floristic Region - Threats.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cape-floristic-region/threats.

[16] Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p 10.

[17] CEPF. “Cape Floristic Region - Threats.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cape-floristic-region/threats.

[18] “Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p 14.

[19] CEPF. “Cape Floristic Region - Priorities.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/cape-floristic-region/priorities.

[20] WWF. “South Africa | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/at1202.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Lowland Fynbos and Renosterveld.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/31202.

[24] Citation needed

[25] “Cape Floral Kingdom,” Conservation International https://www.conservation.org/global/ci_south_africa/where-we-work/cape-floral-kingdom/Pages/cape-floral-kingdom.aspx , Accessed March 18, 2019.

[26] Mahr, Krista. “How Cape Town Was Saved from Running out of Water.” The Guardian , May 4, 2018, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/may/04/back-from-the-brink-how-cape-town-cracked-its-water-crisis .

[27] Goodness and Anderson, 467.

[28] Goodness and Anderson, 466-467.

[29] Goodness and Anderson, find page numbers .

[30] Goodness and Anderson, 486.

[31] Goodness and Anderson, 470.

[32] Ecosystem Profile, CEPF, 5.

[33] Goodness and Anderson, 471.

[34] Goodness and Anderson, 467-468..

[35] “Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p 5.

[36] Unit, Biosafety. “Latest NBSAPs.” Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.cbd.int/nbsap/about/latest/default.shtml#za .

[37] “South Africa’s 2 Nd National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2015 – 2025.” p.20. Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/za/za-nbsap-v2-en.pdf .

[38] “Ecosystem Profile: The Cape Floristic Region, South Africa” Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, December 2001, p. 6.

[39] Ibid.

[40] City Of Cape Town. (2012). Biodiversity network: Methods and results (Technical C-plan & Marxan analysis). Cape Town, South Africa - Municipality Economic, Environmental and Spatial Planning, Directorate Environmental Resource Management Department. https://www.capetown.gov.za/en/EnvironmentalResourceManagement/publications/Documents/BioNet_Analysis-2011_C-Plan+MARXAN_Method+Results_report_2012-06.pdf

[41] City of Cape Town. (2009). Strategic plan 2009-2019. Cape Town, South Africa - Environmental Resource Management Department, Biodiversity Management Branch. https://www.capetown.gov.za/en/EnvironmentalResourceManagement/publications/Documents/Local_Biodiv_Strategy+Action_Plan_(LBSAP)_%202009-2019_v01_2009-07.pdf

[42] City of Cape Town. (2011). Moving mountains: Cape Town’s action plan for energy and climate change. (1st ed.). Cape Town, South Africa. https://www.capetown.gov.za/en/EnvironmentalResourceManagement/publications/Documents/Moving_ Mountains_Energy+CC_booklet_2011-11.pdf