Chengdu, China

- Global Location plan: 30.57oN, 104.07oE [1]

- Hotspot: Qionglai-Minshan Conifer Forests

- Population 2015: 7,556,000

- Projected population 2030: 10,104,000

- Mascot Species: The giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), red panda (Ailurus fulgens), snow leopard (Panthera uncia)

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Amolops ricketti

- Megophrys shapingensis

- Microhyla butleri

- Amolops loloensis

- Fejervarya limnocharis

- Nanorana pleskei

- Rana omeimontis

- Rhacophorus chenfui

- Rhacophorus dugritei

- Andrias davidianus

- Batrachuperus tibetanus

- Polypedates megacephalus

- Amolops lifanensis

- Rhacophorus omeimontis

- Microhyla fissipes

- Hyla annectans

- Leptobrachella oshanensis

- Oreolalax chuanbeiensis

- Oreolalax major

- Oreolalax multipunctatus

- Oreolalax omeimontis

- Oreolalax popei

- Oreolalax rugosus

- Oreolalax schmidti

- Scutiger boulengeri

- Scutiger chintingensis

- Scutiger glandulatus

- Scutiger mammatus

- Megophrys minor

- Megophrys omeimontis

- Megophrys wawuensis

- Kaloula rugifera

- Amolops chunganensis

- Amolops granulosus

- Amolops xinduqiao

- Amolops mantzorum

- Nanorana quadranus

- Quasipaa boulengeri

- Babina daunchina

- Sylvirana guentheri

- Rana kukunoris

- Odorrana margaretae

- Pelophylax nigromaculatus

- Odorrana schmackeri

- Rana zhengi

- Rhacophorus feae

- Rhacophorus hungfuensis

- Batrachuperus karlschmidti

- Batrachuperus londongensis

- Batrachuperus pinchonii

- Tylototriton wenxianensis

- Bufo gargarizans

Mammals

- Catopuma temminckii

- Sciurotamias davidianus

- Sorex cylindricauda

- Myotis frater

- Cuon alpinus

- Vernaya fulva

- Myodes shanseius

- Petaurista alborufus

- Marmota himalayana

- Moschus chrysogaster

- Barbastella leucomelas

- Otocolobus manul

- Ochotona thibetana

- Rhinolophus ferrumequinum

- Procapra picticaudata

- Prionailurus bengalensis

- Ailuropoda melanoleuca

- Rhinopithecus roxellana

- Martes flavigula

- Rhinopithecus roxellana

- Murina aurata

- Ochotona macrotis

- Lepus oiostolus

- Chodsigoa hypsibia

- Sorex bedfordiae

- Episoriculus caudatus

- Chodsigoa lamula

- Nectogale elegans

- Euroscaptor grandis

- Scapanulus oweni

- Uropsilus gracilis

- Mustela altaica

- Mustela kathiah

- Ursus arctos

- Rusa unicolor

- Eothenomys melanogaster

- Rattus nitidus

- Nyctalus plancyi

- Petaurista petaurista

- Ochotona syrinx

- Crocidura vorax

- Elaphodus cephalophus

- Hypsugo alaschanicus

- Sus scrofa

- Petaurista xanthotis

- Apodemus draco

- Rattus rattus

- Rattus pyctoris

- Parascaptor leucura

- Arctonyx albogularis

- Vespertilio sinensis

- Rhinolophus luctus

- Panthera pardus

- Hipposideros pratti

- Pipistrellus abramus

- Rhinolophus sinicus

- Plecotus ariel

- Myotis fimbriatus

- Eptesicus pachyotis

- Panthera uncia

- Mesechinus hughi

- Myotis muricola

- Myotis altarium

- Myotis chinensis

- Rhinolophus macrotis

- Rhinolophus pearsonii

- Myotis davidii

- Myotis laniger

- Ursus thibetanus

- Macaca mulatta

- Mus musculus

- Moschus berezovskii

- Cricetulus longicaudatus

- Macaca thibetana

- Chimarrogale himalayica

- Capricornis milneedwardsii

- Blarinella quadraticauda

- Chimarrogale styani

- Mustela russelliana

- Felis chaus

- Arctonyx albogularis

- Hylopetes alboniger

- Cervus canadensis

- Murina leucogaster

- Eutamias sibiricus

- Petaurista philippensis

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Viverra zibetha

- Viverra zibetha

- Apodemus agrarius

- Herpestes urva

- Muntiacus reevesi

- Eothenomys chinensis

- Erinaceus amurensis

- Lutra lutra

- Ochotona cansus

- Ochotona gloveri

- Euroscaptor longirostris

- Mogera insularis

- Leopoldamys edwardsi

- Sicista concolor

- Eozapus setchuanus

- Niviventer andersoni

- Niviventer excelsior

- Trogopterus xanthipes

- Tscherskia triton

- Tylonycteris pachypus

- Mustela eversmanii

- Scaptonyx fusicaudus

- Dremomys pernyi

- Crocidura attenuata

- Melogale moschata

- Uropsilus soricipes

- Rhizomys sinensis

- Microtus limnophilus

- Volemys millicens

- Paguma larvata

- Vulpes vulpes

- Episoriculus macrurus

- Chodsigoa smithii

- Suncus murinus

- Anourosorex squamipes

- Prionodon pardicolor

- Capreolus pygargus

- Apodemus chevrieri

- Scotomanes ornatus

- Naemorhedus griseus

- Uropsilus andersoni

- Rattus tanezumi

- Hystrix brachyura

- Tamiops swinhoei

- Apodemus peninsulae

- Nyctereutes procyonoides

- Hipposideros armiger

- Micromys minutus

- Rhinolophus affinis

- Volemys musseri

- Vulpes ferrilata

- Martes foina

- Ailuropoda melanoleuca

- Crocidura shantungensis

- Callosciurus erythraeus

- Cervus albirostris

- Myotis formosus

- Mustela sibirica

- Pseudois nayaur

- Pipistrellus pulveratus

- Proedromys bedfordi

- Viverricula indica

- Neodon irene

- Niviventer confucianus

- Meles leucurus

- Aeretes melanopterus

- Ailurus fulgens

- Canis lupus

- Apodemus latronum

- Sorex sinalis

- Berylmys mackenziei

- Budorcas taxicolor

- Lepus tolai

- Sorex excelsus

- Lynx lynx

- Ursus thibetanus

- Crocidura fuliginosa

- Neofelis nebulosa

- Megaderma lyra

- Niviventer fulvescens

- Eospalax fontanierii

- Caryomys eva

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

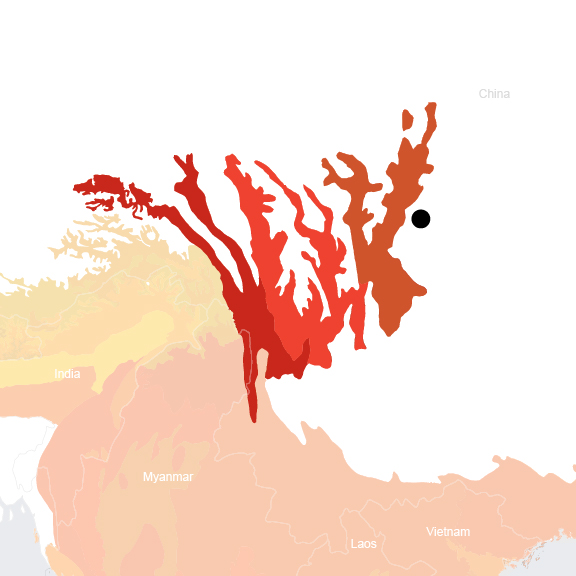

The Mountains of Southwest China Biodiversity Hotspot, which spans from southeast Tibet through western Sichuan and into central and northern Yunnan, is the most botanically rich temperate forest ecosystem in the world. Extreme elevation changes of more than 6,000 m between ridge tops and river valleys foster an entire spectrum of vegetation conditions. The hotspot also sustains great cultural diversity, encompassing 17 of China’s 55 ethnic minority groups. [2]

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~12,000 |

~3,500 |

- 40 percent of all species in China - More than a quarter of the world’s rhododendron species are found in the Hengduan (meaning “Traverse”) Mountains |

|

Birds |

>600 |

1 |

- 25 types of pheasants |

|

Mammals |

>230 |

5 |

- Vulnerable giant panda ( Ailuropoda melanoleuca ), the Endangered red panda ( Ailurus fulgens ), the Endangered golden monkey ( Rhinopithecus roxellana ) - Vulnerable [4] snow leopard (Panthera uncia) - Vulnerable takin ( Budorcas taxicolor ) |

|

Reptiles |

>90 |

~15 |

- mostly snakes and lizards |

|

Amphibians |

~90 |

8 |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

>90 |

~25% |

|

The mountains of southwest China are excessively exploited. Major threats include logging, illegal hunting for wildlife trade, infrastructure construction (promoted by China’s Western Development Program), and fuelwood collection. The national logging ban didn’t take effect until 1998, and state-run enterprises had been commercially harvesting timber from early 1950s. Despite the establishment of a “quota system”, regulations are consistently overwhelmed by political events, development pressure, market demand, or inaccurate inventory statistics. All those destructions have combinedly cause 85 percent loss of old-growth forests along the Upper Yangtze river. [5] CEPF conducted a US$7.9 million investment for conservation of the hotspot from 2002 to 2013, focusing on catalyzing growth in civil society’s and grassroot organizations’ capacity and influence. [6]

Qionglai-Minshan conifer forests

This ecoregion overlaps with the projected growth of Chengdu and is within the hotspot. The mountains which flank the eastern edge of Tibet are some of the highest and steepest on earth, with peaks exceeding 7,500 m. River valleys may cut down to elevations of 1,000 to 2,000 m. The vegetations are stratified by elevations, and conifer forests in this ecoregion dominate the middle and upper elevations, with an understory of arrow bamboo ( Pseudosasa japonica ). A typical sequence of landscapes is pine species ( Pinus tabuliformis, P. armandii ) in drier, lower valleys and spruces ( Picea spp .), Delavay's silver-fir ( Abies delavayi ), and the Chinese larch ( Larix potaninii ) prevalent above 3,000 m. Junipers may appear at the highest elevations, especially at rocky locations with well-drained, basic soils of limestone. Although the forests are classified as coniferous, they also include deciduous broad-leaved trees (maples, birches, rowans, and viburnums) that form a lower canopy. [7]

This ecoregion has been receiving international attention because of the giant pandas ( Ailuropoda melanoleuca ) and other characteristic mammals like the Vulnerable [8] red pandas ( Ailurus fulgens ) and the takins ( Budorcas taxicolor ). This proves to be beneficial for mobilizing national and international conservation efforts for the whole ecosystem, since the region supports very high overall biodiversity. [9] Thanks to action taken in recent years, the giant panda has been recategorized from Endangered to Vulnerable [10] in 2016.

As a result of the mountains’ extreme topography, the human population density is low, and the landscapes remain relatively pristine. Logging is also recently banned in Pingwu County of northern Sichuan in order to control flooding along the Yangtze River. Projects backed by the government consist of participatory forest-use planning, animal conservation, sustainable marketing of non-timber products, and ecotourism. Notwithstanding, even though the growth of tourism contributes to increased funding and awareness, it also exacerbates hunting and illegal wildlife trade. Poaching for fur and pelts of snow leopards, wolves, serows, leopards, and bears are in response to the market demand. [11] Presently, the ecoregion is 8% protected – by three scenic areas and three World Heritage Sites – and is 7.07% connected. [12]

Sichuan Basin evergreen broadleaf forests

The Sichuan Basin ecoregion contains parts of Chengdu but is not within the hotspot. It consists of low limestone hills and alluvial plains completely encircled by mountains. Tibet lies to the west and the north, the Yunnan Plateau extends towards the south, and to the east stretch hundreds of miles of hills cut by the Yangtze River. Because of such enclosed topography, the subtropical area showcases temperature inversions and possesses a very humid, foggy climate with mild winters and warm, hazy summers. The region has historically been agriculturally active because of fertile soils. Cultivated and deforested since ancient times, the remaining patches of climax vegetation scatter across temple forests and holy mountains such as Leshan, Dazushan, and Emeishan. The original landscape in the Sichuan basin was most likely constitute of a mixture of a mixture of subtropical oak ( Quercus , Castanopsis ), Schima ( Theaceae ), and diverse laurel species ( Lauraceae ). Deforested slopes now support scrubs of rhododendrons, sea bilberries ( Vaccinium bracteatum ), and Myrica nana . Sacred mountains for example Emeishan are the main sectors supporting endemic or of restricted range plants and animals; these include species like Tibetan stump-tailed macaque ( Macaca thibetana ) and the bird Emei Shan liocichla ( Liocichla omeiensis ). [13]

The Sichuan Basin has a history of human settlement that goes back for over 5,000 years. The massive historic project Dujiang Irrigation System took place more than 2,000 years ago, and currently the basin is home to more than 100 million people, making it one of the most densely populated agricultural lands in the world. Due to such context, the ecoregion has been greatly modified by agriculture, commerce, and heavy industries in recent decades. Ecosystems closer to original or pristine condition are restricted to steep hillsides and a few temple forests. The degradation of the environment has also led to serious air and water quality issues. [14] Today, only an infinitesimal percentage of the ecoregion is protected (e.g. Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries), and it possesses merely 0.25% of terrestrial connectivity. [15]

Daba Mountains Evergreen Forests

The Daba and Qinling mountain systems oriented east-west and separate the Sichuan Basin to the south from the plains and loess plateaus of northern China. These mountain ranges also serve as a biogeographic barrier and an important watershed division between China’s two greatest rivers, the Yangtze (Changjiang) and the Yellow River (Huang He). The Daba Mountains evergreen forests are sheltered from harsh winter by the topography and enjoy a relatively warm and moist climate with subtropical affinities. The foothills support a mixed evergreen and deciduous palette of oak species and the arboreal mint family ( Lamiaceae spp .). Higher elevations on the other hand foster warm-temperate conifer forests of Chinese red pine ( Pinus massoniana ) and Chinese white pine ( Pinus armandii ). Most of the remaining intact habitat distributes in the eastern part of the ecoregion, on Shennongjia Mountain’s slopes. The mountain has a name associated with an ancient Chinese deity famously associated with medicinal plants, and conserves some of the last primary old growth forests in China. These species include the dove tree ( Davidia involucrata ), Tetracentron ( Tetracentron sinense ), and Katsura ( Cercidiphyllum japonicum ) [16] Several threatened mammal species inhabit this ecoregion, including the Endangered [17] golden snub-nosed monkey ( Rhinopithecus roxellana ), the Endangered [18] forest musk deer ( Moschus berezovskii ), and the Reeve’s pheasant ( Syrmaticus reevesii ). There are also those which come into conflict with local people, such as the wild boar ( Sus scrofa ), the rhesus macaque ( Macaca mulatta ), and the Himalayan black bear ( Selenarctos thibetanus ). [19]

Despite not contained in the Mountains of Southwest China hotspot, the ecoregion encompasses some portions of Chengdu and its biodiversity is threatened by anthropogenic disturbances. Major sources of damage include forest conversion to agriculture, hunting, wildlife harvesting; and they are likely to exacerbate due to ongoing urban expansion. Improved enforcement of conservation regulation and education of locals to raise public awareness is much needed in the region. [20] At present, only 1% of the ecoregion is protected (including Hubei Shennongjia, a World Heritage Site designated in 2016 [21] ), possessing merely 0.49% terrestrial connectivity. [22]

Environmental History

Chengdu emerged as a civilization as early as the bronze age, developing an elaborate irrigation system during the 221-207 BCE Qin dynasty. Indeed, the Dujiangyan Irrigation System was key in mitigating flood risks from the Minjiang river and providing water for the whole region, earning Chengdu the nickname “Land of Plenty.”

Chengdu was founded as a city in 316 BCE, and went on to become the center of Chinese silk production. It grew into a prosperous merchant city, whose traders introduced the first paper currency to China in the 10th century. [23] During World War II, many who fled Japanese invasions on the coast found refuge in Chengdu, stimulating its economic development.

In the early days of the People’s Republic of China, Chengdu’s transportation system was developed and railroads were drawn to connect it to the coast and to the rest fo the province. The city’s industry grew to produce precision-tools, railway equipment, aircraft, defense equipments, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, and more recently electronics and technological products. Today, many of the world’s leading software companies are based in the city, which produces one in two of the world’s computers. [24]

Chengdu’s rural landscape is irrigated thanks to the Dujiangyan System and structured in “Linpan;” small wooded areas that contain houses are scattered across fields, which are connected by irrigation ditches. However, following the terrible 2008 earthquake, China has sought to restructure its rural lands, compromising the overall Linpan system with the destruction of ditches when rural land is converted into urban land. [25]

The rural landscape of Chengdu has a unique layout called “Linpan”, which is a farmhouse surrounded by woods, irrigation ditches “Irrigation Zanja” and farmland. These are important because of their beauty, productivity, and ecological value. [26]

Besides the road, the connection of Linpan are the hierarchy irrigation system of water canals and zanjas from the famous Dujiangyan irrigation system which covered most part of Chengdu plain like people’s circulatory system. Many Linpan were destroyed during the conversion of rural land. They are a linked system to the Dujiangyan irrigation system so one of the papers strategies is to “Recover the quantity of ecological corridor. Reconstruct the zanjas discarded in construction and increase the number of new canals if necessary. ”

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Currently at 7.5 million people, the population of Chengdu is projected to reach 10 million by 2030 . The population growth in Chengdu is formal, and occurs mainly through the densification of the center and in the urbanization of peripheral agricultural lands.

Urbanization usually follows three trends: it grows along the fringe; along transportation corridors and in satellite cities; and then it fills in. Indicators show Chengdu is following this course. [36]

Governance

China is divided into 22 provinces that are further divided into prefectures. The Sichuan province is led by governor Wei Hong, and contains the sub-provincial city of Chengdu, which functions with more autonomy than other prefectures in the province. Mayor Luo Qiang is the head of the Chengdu government, and has jurisdiction over 11 districts, four cities and five counties. [37]

City Policy/Planning

Zoning

In trying to control the growth of its cities, China has developed a new type of urban cluster that combines multiple cities in order to limit their size and improve their management. Once a city reaches its “optimal” population size, its growth is capped, diverting population growth onto other cities in the same cluster. Same-cluster cities are extensively connected with infrastructure that is funded by the central government. The Jing-Jin-Ji region, which contains Chengdu and Chongqing, is projected to become an urban cluster of 60 million people, suggesting that this policy could increase sprawl around existing cities. [38] In an attempt to limit this expansion and protect farmlands and ecosystems, China has defined boundaries for major cities like Chengu . [39]

In 2008, the former Chinese Urban Planning Law was replaced by an Urban and Rural Planning law, showing the country’s will to improve its control over land use in rural areas. China has since focused on restructuring rural areas, namely by relocating villagers into concentrated clusters close to cities, causing the abandonment of more isolated farmlands. The project seems quite beneficial to villagers, but the lack of enforcement of land use policies and the low profitability of arable lands are causing the conversion of farmlands into urban areas. [40]

Indeed, although Chinese policies demand that the country maintain a quota of at least 1.2 million km2 of arable land, this quota is not thoroughly enforced. The state owns urban land, and grants ownership of rural land to village collectivites. Although such laws seem to limit urban expansion, they may enable local government officials to profit from conversions of rural land to urban areas, as suggested by Jesper Willaing Zeuthen. His 2017 article explains that quota conversions lead to the formation of local agencies that villagers cannot participate in. Thus, inhabitants of rural lands are often displaced into denser, government-managed peri urban areas, or left with unusable land that they are not allowed sell. [41]

The Chengdu City Plan 2016-2030 addresses the urban area as the “1+7 Chengdu Plain City cluster.” One of its goals is “to build a pretty and liveable garden city,” and to promote “smart growth” and the green and intensive development of Chengdu. Transportation infrastructure is a major component of the plan, with the provision of eight new subway lines to be added to the existing two by 2020, and the overall creation of 1696 km of urban raillines. [42]

The Urban Agglomeration (UA) development plan currently overstates the number of UAs and their spatial extension. Page 13 of this document shows the Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration. [43]

Among its green projects, the Longquanshan Urban Forest Park is to be upgraded to an area of over 1,200 km2, serving as both a conservation habitat and an “international city meeting room” that will host diverse human activities. [44]

Aside from this park, however, the idea of a garden city seems to focus on developing leisure areas, where vegetation function primarily aesthetically rather than underpinning habitat restoration. Indeed, the apparent lack of a spatial plan in Chengdu underlines the problem raised by Ha Li of TAO architects, at the 2011 Changdu Architecture Biennale: “A garden city needs to go beyond image, beyond a cityscape simply sprinkled with plants.” [45]

Two New City development master plans were drawn by the Adrian Smith and Gordon Gill architecture firm. One of them, the Chengdu Great City, will be built from scratch to house 80,000 people in an environmentally friendly community. Gordon speaks of “harmony with nature” and says that the design “embraces the surrounding landscape,” yet the firm’s renderings depict an environment that seems focused on pleasantness rather than respect for nature . [46] [47]

The other project by the firm, the master plan for the Tianfu New District, lists natural environment conservation as one of its goals. Yet, once more, the designated natural area resembles an enjoyable park more than a reserve. [48]

Many other master plans by firms like Yamasaki, MHKW, RTKL, John McAslan and Partners, and HOK all present similar projects for green areas , without any real efforts for conservation. [49] Thus, the vision of a Garden City includes many projects for green areas in Chengdu, but biodiversity protection and restoration do not seem like priorities in planning.

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

China's revised NBSAP (2011-2030) was developed with the draft Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 taken into account. [50] It recognizes accelerated urbanization and industrialization as one of the major sources of threat. [51] The plan’s fifth priority is the Alpine Canyon Region of Southwest China, which includes portions of the the Hengduanshan Mountain and of the Minshan Mountain, in Sichuan. Only 7.8% of this area is protected, further threatening the Giant Panda ( Ailuropoda melanoleuca ), the Golden Monkey ( Cercopithecus kandti ), the Bengal Tiger ( Panthera tigris tigris ), and the Indo-China Tiger ( Panthera tigris corbetti ), which the plan identifies as priority species. The plan also seeks to protect genetic resources and knowledge of traditional medicine in the region. [52]

Although it recognizes successful efforts like the ex-situ conservation of over 80% of threatened species of small, wild populations , the plan also identifies multiple tasks to guide future initiatives in China. The first of these address the need to improve policies, administration, and implementation efforts relevant to conservation, as well as to increase resources for such projects. The plan emphasizes the importance of using natural resources sustainably and of sharing the benefits reaped from conservation. Awareness-raising also occupies an important place in the plan, as does the capacity to address new biodiversity threats. [53]

On a more local level, the Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Forestry aims to protect biodiversity in the area, under the supervision of the Office for Wildlife Protection and Natural Conservation Area Administration . [54]

Protected Areas Near City

Two key protected areas are found near Chengdu: the Wolong reserve and the Huanglang-Wanglang-Jiuzhaigou complex reserve. The main threats in these areas are logging and hunting, which threaten species like the Snow Leopard, the Wolf, the Serow, and the Black Bear. [55]

Wolong park also includes the Gengda Wolong Panda Center which conducts research and conservation efforts, namely breeding. Despite these efforts, however, increased tourism in the reserve has only further fragilized its ecosystems . [56]

Another relevant zone is Mount Emei, a “Scenic Area” south of Chengdu. The mountain is a UNESCO world heritage site and provides a habitat for 31 plant species that are under national protection.

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CCF) have worked to protect Pandas in the region, namely through the creation of the WWF Chengdu Programme Office in 2002. One of the office’s programme focuses on Ping Wu, a low-income county whose citizens rely on local natural resources to live. A report by the CEPF reveals that local ecosystems are mainly threatened by logging, illegal hunting, infrastructure development without environmental impact reports, and tourism in highly visited reserves. [57]

The World Associations of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) has developed the Sichuan Forest Biodiversity Project whose objectives include creating monitoring programs, conducting research on key species, promoting community-based efforts, improving the administration of reserves, increasing awareness and education, namely through schools and reserve-led “visitor management strategies. The project also underlines the importance of maintaining sufficient connectivity in the area’s ecosystems. [58]

The Nature Conservancy has created the Sichuan Nature Conservation Foundation (SCNF), which designed the Laohegou Land Trust Reserve. This conservation area aims connect existing reserves, in a zone with the highest panda density in the world. The area also provides a habitat to Golden Snub-nosed Monkeys and Asian Golden Cats. The foundation also aims to help locals who rely on hunting, fishing and gathering, to find alternative solutions for living. [59]

More locally, the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, focuses on both breeding itself and biodiversity education. It mentions exposure to nature as an essential component to awareness-raising. [60] Generally, the region’s focus on Pandas can be explained by the species’ popularity among citizens.

Public Awareness

The National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan admits that awareness in China is still quite low. A study by Susan Clayton et al. suggests that the main problem lies in the belief that citizens cannot truly contribute to conservation efforts. The study explains awareness campaigns in Chengdu zoos could be effective in motivating citizens to contribute to conservation efforts. [61]

[2] CEPF. “Mountains of Southwest China.” Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-southwest-china.

[3] CEPF. “Mountains of Southwest China - Species.” Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-southwest-china/species.

[4] “Snow Leopard.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[5] CEPF. “Mountains of Southwest China - Threats.” Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-southwest-china/threats.

[6] CEPF. “Mountains of Southwest China.” Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-southwest-china.

[7] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Southern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0518.

[8] “Red Panda.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed June 6, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[9] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Southern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0518.

[10] “Giant Panda.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed June 6, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[11] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Southern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0518.

[12] “Qionglai-Minshan Conifer Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/80518.

[13] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Southern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0437.

[14] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Southern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0437.

[15] “Sichuan Basin Evergreen Broadleaf Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/80437.

[16] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Eastern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0417.

[17] “Golden Snub-Nosed Monkey.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed June 6, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[18] “Forest Musk Deer.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed June 6, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[19] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Eastern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0417.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Hubei Shennongjia.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed June 6, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/wdpa/555622042.

[22] “Daba Mountains Evergreen Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/80417.

[23] Top China Travel, “Chengdu History,” https://www.topchinatravel.com/chengdu/chengdu-history.htm (accessed June 30, 2018)

Catherine Jessup, “The colourful story of Sichuan’s silk brocade,” GB Times (October 9, 2017), https://gbtimes.com/the-colourful-story-of-sichuans-silk-brocade

Go Chengdu, “Chengdu: Start Point of Southern Silk Road” http://www.gochengdu.cn/travel/feature/what-is-southern-silk-road--a319.html (accessed June 30, 2018)

Travel China Guide, “Dujiangyan Irrigation System,” https://www.travelchinaguide.com/attraction/sichuan/chengdu/dujiangyan.htm (accessed June 30, 2018)

[24] Encyclopedia Britannica, “Chengdu,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Chengdu (accessed June 30, 2018)

Lucy Bullivant, “Chengdu, China: big city symbiosis,” Urbanista.org , 1 (2012), http://www.urbanista.org/issues/issue-1/features/chengdu-big-city-symbiosis

[25] Yang Qingjuan, Li Bei, Li Kui, The Rural Landscape Research in Chengdu's Urban-rural Intergration Development, Procedia Engineering, Volume 21, 2011, Pages 780-788, ISSN 1877-7058, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2078.

[26]

Yang Qingjuan, Li Bei, Li Kui, The Rural Landscape Research in Chengdu's Urban-rural Intergration Development, Procedia Engineering, Volume 21, 2011, Pages 780-788, ISSN 1877-7058, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2078.

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877705811049125)

[29] Mission China, “Chengdu - Historical Data,” http://www.stateair.net/web/historical/1/2.html (accessed June 30, 2018)

Mission China, “Chengdu - PM2.5,” http://www.stateair.net/web/post/1/2.html (accessed June 30, 2018)

World Health Organization, “WHO Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide” 2005

[30] Nectar Gan, “Watershed crisis: China’s cities tap into sea of polluted water,” South China Morning Post (April 20, 2016), http://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/1937228/watershed-crisis-chinas-cities-tap-sea-polluted-water

[31]

Yifan Li, Jinyan Zhan, Fan Zhang, Miaolin Zhang, Dongdong Chen, The study on ecological sustainable development in Chengdu, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 2017, ISSN 1474-7065, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2017.03.002.

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474706516300675)

[32]

Yifan Li, Jinyan Zhan, Yu Liu, Fan Zhang, Miaolin Zhang, Response of ecosystem services to land use and cover change: A case study in Chengdu City, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2017, ISSN 0921-3449, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.03.009.

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344917300885)

[33]

Yifan Li, Jinyan Zhan, Fan Zhang, Miaolin Zhang, Dongdong Chen, The study on ecological sustainable development in Chengdu, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 2017, ISSN 1474-7065, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2017.03.002.

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474706516300675)

[34]

Yifan Li, Jinyan Zhan, Yu Liu, Fan Zhang, Miaolin Zhang, Response of ecosystem services to land use and cover change: A case study in Chengdu City, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2017, ISSN 0921-3449, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.03.009.

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344917300885)

[35] University of Central Lancashire Confucius Institute, “Biodiversity & China,”

[36] Schneider, A., Seto, K., & Webster, D. (n.d.). Urban Growth in Chengdu, Western China: Application of Remote Sensing to Assess Planning and Policy Outcomes. Environment and planning., 32(3). doi:10.1068/b31142

[37] Sichuan Province People’s Government, “Leaders,” http://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/wza2012/english/leaders/english_leaders.shtml (accessed June 30, 2018)

Chengdu China, “Mr. Luo Qiang, Mayor,” http://www.chengdu.gov.cn/english/government/2018-01/31/content_4a40a5e635f6445a851949157c9bdd01.shtml (accessed June 30, 2018)

[38] Helen Roxburgh, “Endless cities: will China's new urbanisation just mean more sprawl?” The Guardian (May 5, 2017) https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/may/05/megaregions-endless-china-urbanisation-sprawl-xiongan-jingjinji

[39] http://citiscope.org/citisignals/2015/fourteen-chinese-cities-get-tough-urban-sprawl

“14 cities to draw red line to stop urban sprawl” China Daily (2015), http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2015-06/05/content_20913209.htm

[40] Jessica Wilczak, Making the countryside more like the countryside? Rural planning and metropolitan visions in post-quake Chengdu, Geoforum, Volume 78, 2017, Pages 110-118, ISSN 0016-7185,

Database of Laws and Regulations, “Law of the People's Republic of China on Urban and Rural Planning” http://www.npc.gov.cn/englishnpc/Law/2009-02/20/content_1471595.htm (accessed June 30, 2018)

[41] Zeuthen, J.W., Land Use Policy (2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.009

[42] Party Central Committee, Party Provincial Comittee, Sichuan Provincial Government, Chengdu City Government, “Chengdu City Master Plan, 2016-2035,” 2016

Lucy Bullivant, “Chengdu, China: big city symbiosis,” Urbanista.org , 1 (2012), http://www.urbanista.org/issues/issue-1/features/chengdu-big-city-symbiosis

[43]

Xiao-lu Gao, Ze-ning Xu, Fang-qu Niu, Ying Long, An evaluation of China’s urban agglomeration development from the spatial perspective, Spatial Statistics, 2017, ISSN 2211-6753, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spasta.2017.02.008.

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211675317300829)

[44] Party Central Committee, Party Provincial Comittee, Sichuan Provincial Government, Chengdu City Government, “Chengdu City Master Plan, 2016-2035,” 2016

[45] Lucy Bullivant, “Chengdu, China: big city symbiosis,” Urbanista.org , 1 (2012), http://www.urbanista.org/issues/issue-1/features/chengdu-big-city-symbiosis

[46] Rebecca Boyle, “China Is Building A Brand New Green City From Scratch,” Popular Science (October 25, 2012), https://www.popsci.com/technology/article/2012-10/carefully-engineered-chinese-pocket-city-will-fight-sprawl-building-not-out

[47] Adrian Smith + Gosrdon Gill Architecture, “Great City Chengdu Master Plan”

[48] Adrian Smith + Gosrdon Gill Architecture, “Tianfu New District Master Plan”

[49] Yamasaki, “Planning,” https://www.yamasaki-inc.com/copy-of-mixed-use (accessed June 30, 2018)

John MCaslan + Partners, “Chengdu Community Masterplan,” http://www.mcaslan.co.uk/projects/chengdu-community-masterplan (accessed June 30, 2018)

HOK, “A Modern Town Refelcts Ancient Sichuan Culture, Chengdu Meng Yang New Town Master Plan,” http://www.hok.com/design/region/asia-pacific/chengdu-meng-yang-new-town-master-plan/ (accessed June 30, 2018)

Sebastian Jordana, “New CHengdy City Center / RTKL,” ArchDaily (Novermber 20, 2010), http://www.archdaily.com/88195/new-chengdu-city-center-rtkl

MHKW, “Chengdu South District Master Plan,” http://www.mhkw.com/Chengdu%20South%20District%20Masterplan.html (accessed June 30, 2018)

[50] Unit, Biosafety. “Latest NBSAPs.” Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.cbd.int/nbsap/about/latest/default.shtml#cn .

[51] Unit, Biosafety. “China - Country Profile.” Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/default.shtml?country=cn#facts .

[52] Ministry of Environmental Protection, “China National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan, 2011-2030” 2011

[53] Ministry of Environmental Protection, “China National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan, 2011-2030” 2011

[54] People’s Government of Sichuan Province, “Sichuan Provincial Bureau of Forestry,” http://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/10758/10759/10763/2010/10/28/10147563.shtml (accessed June 30, 2018)

[55] World Wildlife Fund, “Eastern Asia: Southern China,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0518 (accessed June 30, 2018)

[56] Global Species, “Wolong Nature Reserve,” http://www.globalspecies.org/protectareas/display/224 (accessed June 30, 2018)

Wei Liu et al., “Evolution of tourism in a flagship protected area of China,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24, 2 (2016) https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09669582.2015.1071380?scroll=top&needAccess=true

Alexandra E. Petri, “3 Places to See China's Giant Pandas,” National Geographic Traveler Magazine (August 16, 2016), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/destinations/asia/china/places-to-see-giant-panda-china-nature-reserve/

Joanna Ruck, “Inside the giant panda research centre - in pictures,” The Guardian (April 23, 2014), https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2014/apr/23/inside-the-giant-panda-research-centre-in-pictures

[57] WWF China, “Chengdu Office,” http://en.wwfchina.org/en/who_we_are/where_we_work/chengdu_office/ (June 30, 2018)

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Mountains of Southwest China,” https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-southwest-china (accessed June 30, 2018)

[58] World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, “Sichuan Forest Biodiversity Project,” http://www.waza.org/en/site/conservation/waza-conservation-projects/sichuan-forest-biodiversity-project (accessed June 30, 2018)

[59] National Geographic, “Transforming Conservation in China with ‘Land Trust Reserves,’” https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2016/08/24/transforming-conservation-in-china-with-land-trust-reserves/ (accessed June 30, 2018)

[60] Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, “Conservation Overview,” http://www.panda.org.cn/english/conservation/overview/2013-09-12/2432.html (June 30, 2018)

[61] Susan Clayton et al. “Confronting the wildlife trade through public education at zoological institutions in Chengdu, P.R. China,” Zoo Biology 37, 2 (February 5, 2018)