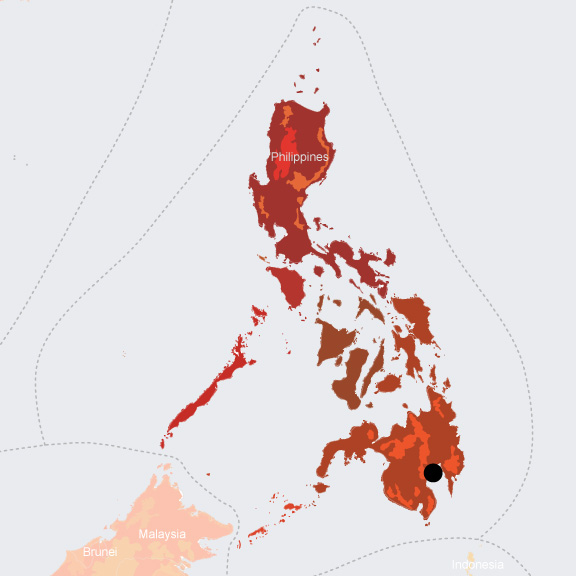

Davao, Philippines

- Global Location plan: 7.19oN, 125.46oE[1]

- Hotspot: Mindanao-Eastern Visayas Rain Forests

- Population 2015: 1,630,000

- Projected population 2030: 2,216,000

- Mascot Species: Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi) (endemic and critically endangered)

- Crops: bananas, coconut, rice, sugarcane, corn, durian and mango[2]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Philautus acutirostris

- Kurixalus appendiculatus

- Philautus worcesteri

- Rhinella marina

- Ichthyophis mindanaoensis

- Philautus surdus

- Rhacophorus bimaculatus

- Philautus poecilius

- Pulchrana guttmani

- Nyctixalus spinosus

- Nyctixalus spinosus

- Nyctixalus spinosus

- Limnonectes parvus

- Fejervarya cancrivora

- Fejervarya vittigera

- Hylarana erythraea

- Philautus acutirostris

- Rhacophorus pardalis

- Pulchrana grandocula

- Pulchrana grandocula

- Pulchrana grandocula

- Sanguirana everetti

- Lithobates catesbeianus

- Limnonectes ferneri

- Staurois natator

- Pelophryne lighti

- Philautus surrufus

- Rhacophorus bimaculatus

- Leptobrachium lumadorum

- Platymantis rabori

- Platymantis guentheri

- Occidozyga laevis

- Philautus leitensis

- Philautus leitensis

- Ansonia mcgregori

- Ansonia muelleri

- Limnonectes magnus

- Megophrys stejnegeri

- Chaperina fusca

- Kalophrynus pleurostigma

- Kaloula picta

- Oreophryne anulata

- Platymantis corrugatus

- Sanguirana mearnsi

- Sanguirana mearnsi

- Polypedates leucomystax

- Limnonectes leytensis

- Kaloula conjuncta

- Pelophryne brevipes

Mammals

- Ptenochirus jagori

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Mesoplodon ginkgodens

- Mops sarasinorum

- Eonycteris robusta

- Podogymnura truei

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Crocidura beatus

- Rattus tanezumi

- Rhinolophus arcuatus

- Falsistrellus petersi

- Megaderma spasma

- Sundasciurus davensis

- Hipposideros ater

- Macroglossus minimus

- Exilisciurus concinnus

- Tylonycteris pachypus

- Pteropus vampyrus

- Coelops robinsoni ssp. hirsutus

- Haplonycteris fischeri

- Limnomys bryophilus

- Balaenoptera omurai

- Cynocephalus volans

- Cheiromeles parvidens

- Hipposideros obscurus

- Peponocephala electra

- Tursiops truncatus

- Tursiops aduncus

- Rattus rattus

- Taphozous melanopogon

- Dugong dugon

- Stenella longirostris

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Hipposideros pygmaeus

- Rousettus amplexicaudatus

- Scotophilus kuhlii

- Myotis macrotarsus

- Miniopterus tristis

- Cynopterus luzoniensis

- Rhinolophus virgo

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Kerivoula whiteheadi

- Miniopterus australis

- Pipistrellus javanicus

- Myotis horsfieldii

- Emballonura alecto

- Rhinolophus rufus

- Pipistrellus tenuis

- Rhinolophus inops

- Tarsomys echinatus

- Sus philippensis

- Pteropus hypomelanus

- Mus musculus

- Mus musculus

- Crunomys melanius

- Grampus griseus

- Chaerephon plicatus

- Acerodon jubatus

- Eonycteris spelaea

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Hipposideros ater

- Orcinus orca

- Rusa marianna

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Philetor brachypterus

- Megaderma spasma

- Viverra tangalunga

- Limnomys bryophilus

- Lagenodelphis hosei

- Batomys hamiguitan

- Dyacopterus spadiceus

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Megaerops wetmorei

- Saccolaimus saccolaimus

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon hotaula

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Paradoxurus hermaphroditus

- Sundasciurus philippinensis

- Tupaia everetti

- Rhinolophus arcuatus

- Tarsomys apoensis

- Indopacetus pacificus

- Suncus murinus

- Sundasciurus mindanensis

- Petinomys mindanensis

- Tarsius syrichta

- Macaca fascicularis

- Hipposideros cervinus

- Stenella attenuata

- Rattus exulans

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Kogia sima

- Apomys insignis

- Alionycteris paucidentata

- Crunomys suncoides

- Apomys hylocetes

- Bullimus bagobus

- Feresa attenuata

- Harpyionycteris whiteheadi

- Harpyionycteris whiteheadi

- Hipposideros diadema

- Hipposideros diadema

- Kerivoula pellucida

- Macaca fascicularis

- Ptenochirus minor

- Murina cyclotis

- Rattus everetti

- Petinomys crinitus

- Limnomys sibuanus

- Alionycteris paucidentata

- Apomys littoralis

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Batomys salomonseni

- Kogia breviceps

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Kerivoula hardwickii

- Rhinolophus subrufus

- Rattus argentiventer

- Bullimus bagobus

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Philippines Hotspot comprises more than 7,100 islands in the westernmost Pacific Ocean. Its diverse topography includes rugged volcanic mountains, plateaus, vast fertile plains (which have mostly been converted to cropland), and long coastlines with some of the world’s most colorful coral reefs. [3]

Species statistics [4]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

9,250 |

>33% |

- 150 types of palm (67% endemic) - 1,000 types of orchids (70% endemic) |

|

Birds |

>530 |

35% |

Critically Endangered Philippine eagle ( Pithecophaga jefferyi ) |

|

Mammals |

>165 |

61% |

Endangered golden-capped fruit bat ( Acerodon jubatus ) |

|

Reptiles |

235 |

68% |

|

|

Amphibians |

~90 |

85% |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

>280 |

>23% |

|

|

Invertebrates |

~21,000 |

~70% |

|

The patchwork of isolated islands and the country’s tropical location resulted in the Philippines hotspot’s high species diversity and very high levels of endemism. Amongst plants, begonias, gesneriads, orchids, pandans, palms, and dipterocarps are particularly high in endemics. BirdLife International has identified seven Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs) in the hotspot. One notable species is the Critically Endangered Philippine eagle [5] ( Pithecophaga jefferyi ), the second-largest eagle on earth. It inhabits only four islands (including Mindanao), and because of its monogamous mating habits and long parenting cycles, breeding programs in captivity have been unsuccessful. Amphibians are well represented in the hotspot by frogs, many of which are endemic and threatened. The region is also exceptionally rich in invertebrates, especially in butterflies and tiger beetles. [6]

The Philippines is one of the most degraded hotspots around the globe, with only about seven percent of its original old-growth, closed-canopy forests left. Threats to biodiversity here include extractive industries – mining, logging, fishing, and associated road building. Regulation enforcement is inconsistent and impeded by limited resources. The increasing population often migrate in substantial numbers between islands, bringing along the destructive shifting cultivation, posing significant pressure to the ecosystems. The urban sprawl also leads to loss of indigenous knowledge and practices, which are pro-conservation. Other sources of damage include hunting, poaching, and flora collection. Conflicting policies on both national and local levels are another issue. [7]

CEPF invested US$7 million in the Philippines hotspot from 2002 to 2007. Resources concentrated in Eastern Mindanao, Palawan, and Sierra Madre corridors. The funds created and expanded protected areas, while ensuring their management. [8]

Mindanao-Eastern Visayas Rain Forests

Davao City is located in the Mindanao-Eastern Visayas Rain Forests ecoregion of the Philippines, and to the west near the Mindanao Montane Rain Forests ecoregion. The Mindanao-Eastern Visayas Rain Forests ecoregion features lowland and hill forests on a few large Philippine islands – Mindanao, Samar, Leyte, Bohol – which were part of one island during the last ice age, and numerous smaller satellite isles. The climate is tropical wet, with typhoons occurring from July to November contributing as much as one-third of annual rainfall in some areas. The dominant forest type in the ecoregion was dipterocarp forest. Those trees are known as the Philippine mahogany in the timber trade. In lowland areas, the forest is quite tall (45-65 m) and dense, with three canopy layers. At higher elevations the canopy only has two layers, featuring more epiphytes and the tree stature is lower. Fauna in this ecoregion have been migrating from and to Borneo for millennia, and mammals have particularly high levels of endemism, especially on Mindanao. The ecoregion overlaps with the Mindanao and Eastern Visayas EBA, containing more than 50 restricted-range birds. [9] Notable endemic and threatened species include the Vulnerable [10] Mindanao bleeding-heart ( Gallicolumba criniger ) and the Critically Endangered Philippine eagle [11] ( Pithecophaga jefferyi ). Both of their resident regions cover Davao city.

The lowland forests’ situation is particularly dire compared with that of the higher, montane regions. Some areas which now are suspended from logging are in turn threatened by encroaching agriculture and fire. Other main threat to biodiversity and habitat loss include firewood and rattan collection, hunting, trapping, and commercial forestry. [12] At present, 9 percent of the ecoregion is protected, which has a 4.65 percent terrestrial connectivity. [13]

Mindanao Montane Rain Forests

The Mindanao Montane Rain Forests ecoregion is situated solely in the upland regions of Mindanao island. Its climate is tropical wet, with temperature and rainfall modified by elevation, which reaches up to 2,700 m. The vegetation consists of hill dipterocarp forests, elfin woodlands (mossy), and summit grasslands. There are also many epiphytes (mostly tree ferns and orchids) and palms. Mt. Apo, near the city of Davao, is considered a Centre of Plant Diversity. [14] Notable endemic and threatened species in the ecoregion include the Vulnerable blue-capped kingfisher [15] ( Actenoides hombroni ), the Vulnerable [16] Philippine warty pig ( Sus philippensis ), and the Vulnerable [17] Philippine deer ( Rusa marianna ). All three animals have ranges near Davao and suffer from habitat destruction. Conservation is essential for the Mindanao Montane Rainforests particularly because most of the lowland forests have already been cleared. Logging and shifting cultivation (called “kaingin” in the Philippines) are the major threats to biodiversity in the ecoregion. [18] Currently, 24 percent of the ecoregion is under protection, which is 12.2 percent terrestrially connected. [19]

Environmental History

After 300 years of Spanish rule, the Philippines were successively annexed by the United States, made autonomous, re-annexed by the United States and finally made independent in 1946. The dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos from 1965 to 1986 left the country vulnerable to corruption and Islamist insurgency in the south. [20] As the mayor of Davao City from 1988 to 2016, current president Rodrigo Duterte led extremely aggressive policies to reduce crime and drug dealing in the area. Today, as a very attractive city, Davao is growing fast due to high immigration, which is causing informal settlements to grow on the edges of the city. Economically, the region offers rich agricultural, mineral and marine resources that further contribute to its attractiveness. [21]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

The biggest known environmental concerns in Davao City are linked to poor waste and water management due to the city’s rapid and informal expansion, including poor waste segregation given the region’s intensive agricultural production. [22] Forest cover is present just outside of the city, although it is extremely fragmented and threatened by growing settlements.

The closest conserved forest cover is found in Mount Apo, which contains both the Mindanao-Eastern Visayas Rain Forests and Mindanao Montane Rain Forests. Most of the cover has been cleared below 1,000m, and what remains is threatened by land conversion for agriculture, plant collection and trekking by visitors, ineffective forest protection and the proliferation of alien invasive species. [23]

The watersheds of the city, which provide its residents with drinkable water, are also a major environmental concern. Both Talomo and Panigan-Tamugan watersheds are threatened by unregulated development including banana and pineapple plantations. [24]

Despite the presence of some peri-urban forest restoration projects, satellite imaging reveals that the relentless and uncontrolled expansion of informal settlements, farmlands and residential developments still poses a major threat to the forest cover that surrounds the city and the biodiversity that it shelters.

Indeed, the Davao Region Physical Framework Plan identifies Population Growth as the biggest threat to biodiversity, followed by poverty, which causes food insecurity and puts pressure on neighboring ecosystems. Other major threats relate to logging, mining, or farming. Both non-compliant logging companies and general illegal logging pose a threat to ecosystems, as do open pit and strip mining. The agricultural sector further weakens local biodiversity through land conversions, namely the conversion of forest to farmland and the adoption of high-yielding or non-native crops, or permanent farming. [25]

Overall, the biggest obstacles to biodiversity conservation in Davao have to do with the city’s uncontrolled expansion and high level of poverty, which is causing food insecurity and the formation of precarious settlements.

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Officially, Davao City’s population has grown from 392,500 in 1970 to 1,449,300 in 2010, or a mean growth rate of 2.6% over forty years. [26] The city owes this growth to its natural resources and to its popularity due to the mandate of Rodrigo Duterte and its legacy with his daughter “Inday Sara” Duterte, current mayor of Davao. [27]

In 2005, an estimated 20%of single houses were built on land that the residents did not own or pay for, categorized as “rent-free with consent of the owner.” Another 16,000 families resided on land without the owner’s consent, resulting in a total estimate of 340,000 informal settlers for that year. [28]

In response to the growth of settlements, Davao City is planning for the construction of four 50ha artificial islands in the Gulf of Davao. The additional land is to provide space for new public and commerce spaces, and allow for the relocation of 3,500 slum-dwellers. [29]

Governance

The Philippines are divided into 17 regions, 16 of which are under control of the Philippine government. The Davao Region, or Region XI, is divided into six provinces including Davao City. Each province is further divided into cities and municipalities, which are themselves made up of Bangarays.

The Philippines are headed by elected president Rodrigo Duterte, whose daughter Sara Inday Duterte is the mayor of Davao City.

City Policy/Planning

Development Plan

The Mindanao Spatial Strategy accounts for a the Davao River Basin Development program, which focuses on improving the quality of water delivered to residents. [30] The document also covers the National Greening Program, which achieved its objective of planting 1.5 billion trees in 2018, covering 1.5 million ha. [31] The Enhanced national Greening Program (ENGP) extended the target by an additional 1.2 million ha, to be covered by 2022. [32] The program is an “integrated approach to ecosystem management and governance,” since tree species were chosen based on the site of the planting. [33]

One of the 21 chapters of the Davao Regional Plan 2017-2022 is dedicated to protecting the environment. The Plan aims to conserve and protect the forest cover in the region, as well as to improve the state of local biodiversity and the quality of air and water. [34]

An area of 71,000ha of forest cover was created in Davao Region, thanks in part to the Treevolution project of Mindanao Nurturing our Waters (MindaNOW), a program that includes reforestation in its effort to improve the management of watersheds on the island. In one instance, the Treevolution campaign sought to beat a Guinness World Record, planting over 2.2 million trees in a day with the help of 122,000 participants. The Davao Regional Plan aims to create an additional 45,000ha of forest cover by 2022, and has submitted two potential protected areas for review to the National Government in addition to the two protected areas that were created since 2009. [35]

It also lists priority research areas, including the assessment and valuation of natural resources.

The Regional Plan underlines major obstacles in biodiversity conservation, namely government inefficiency due to overlapping functions and poor enforcement. The plan has taken a first step in solving these problems with the creation of four task-forces to curb illegal logging, in coordination with multiple governmental agencies. [36]

The Davao Region Physical Framework plan 2015-2045 addresses biodiversity conservation with three goals: the protection of critical areas from human intrusion and exploitation, the balance between resource use and biodiversity, culture and historical values, and the improvement of disaster mitigation. [37]

By 2025, the Framework Plan intends to expand the Mt. Hamiguitan Range and Wildlife Sanctuary and to create two new protected areas: the San Isidro Protected Seascape and the Mt. Tagub-Kampilili Protected Landscape. It also accounts for the implementation of the Eastern Mindanao Biodiversity Corridor (EMBC), which contains nine Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA), and for the formulation of 13 Local Government Unit (LGU) Forest Land Use Plans (FLUPs). [38]

By 2045, the Plan aims to conduct surveys and demarcation of non-protected areas, especially that are environmentally critical. The plan also includes the creation of new legislation for protected areas, and the intensification of forest rehabilitation. [39]

Another development plan at the regional scale, the Davao Gulf Area Development Plan 2011-2030, addresses environmental concerns, including policy enforcement and the promotion of green industries and jobs. The Plan also mentions the Urban Forestry Project, a local contribution to the National Greening Program that is supervised by the Ecology Section of the Parks and Playgrounds Division. [40]

Zoning [41]

Davao City Zoning is clearly defined and accounts for Forest Zones, where the only authorized infrastructure is that of indigenous communities, and Conservation Zones, where commercial tree farming, harming species, construction, and mineral exploitation are all prohibited. [42] Thus, the main limitations to zoning in Davao concern the small size of the area covered by protected areas, and the difficult enforcement of the code, apparent in the abundance of informal settlements and illegal activities.

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

The National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan of the Philippines was last updated in 2015. It includes a report on the current status of the country’s ecosystems and reveals that much of Philippine biodiversity is still in the process of being discovered. For instance, 300 species were discovered in 2011 by the California Academy of Sciences. The Plan covers the management of the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS). It explains that out of the 240 protected areas in the country, 91 are situated in some 228 Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA) which were identified in 2006 by the Biodiversity Management Bureau of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources [43] . Existing protected areas face many challenges, first of which being the previously discussed conversion of forest into agricultural land. Other obstacles include illegal timber extraction, the advancement of human settlements in protected areas, and unregulated tourism. The plan also discusses administrative limitations due to overlapping policies, limited financial resources and lack of data on protected areas. The Plan cites the Expanded NIPAS (ENIPAS) Bill, which strengthens the existing system. Indeed, until recently, only 13 protected areas were in fact legally secured through NIPAS. Fortunately, ENIPAS was recently approved by the Philippine House of Representatives, enabling the full legal protection of over 100 protected areas. [44]

National

In addition to its NBSAP, the Philippines supports international agreements through its Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas, which sets multiple targets for 2020. By that year, 50% of protected areas should be supervised full-time by Protected Area Superintendents and joined by three ecological corridors, and the NIPAS should cover 80% of threatened species. At least 75% of core funding for protected areas should be secured and managed through a trust fund, and other funding methods should be developed for at least 30 protected areas. The Plan also seeks to recognize community conserved areas and integrate at least 10 priority areas into the National Climate Adaptation Strategy. [45]

The Plan lists the previously mentioned threats to biodiversity, emphasizing that 137 of the 228 Key Biodiversity Areas are completely unprotected. It identifies difficult biogeographical representativeness, poor enforcement and management, and inadequate financial planning as the major obstacles to conservation. [46]

The heart of national conservation efforts is the Philippine Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB), within the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). The Bureau aims to combat species extinction, promote biodiversity-friendly practices and strengthen the implementation of NIPAS, through policy recommendations and endangered species listings. It focuses on three components of biodiversity: genetic resources, ecosystems and endangered species. [47]

The DENR benefits from the support of the German Society for International Cooperation through the Protected Area Management Enhancement Project (PAME). Germany has helped improve government efficiency by training employees to increase their management skills and technical expertise. PAME aims to improve 60 existing protected areas and to create another 100. The project also includes the enhancement of information management and awareness-raising. [48] Some of PAME’s recommendations include collaborating with local governments and non-governmental organizations to facilitate policy harmonization, and seeking external support to develop updated plans and databases. [49]

The Forest Management Bureau (FMB) of the DENR is another major pillar of conservation. Its Philippine Master Plan for Climate Resilient Forestry Development identifies multiple obstacles to the attainment of the global objectives formulated by the 2010 FAO Global Forest Assessment. These objectives include reversing the loss of forest cover, enhancing forest-based economic, social and environmental benefits, increasing the area of protected forests and administrative resources for sustainable forest management. The Plan highlights the sensitivity of mangroves to sea-level rise and of highlands to climate change. It explains that logging, deforestation and landslides increase risks of natural disasters caused by climate change, amounting to an estimated Php 19.7 billion (369 million USD) in damage per year between 1990 and 2008. Thus, the Master Plan reveals that forest conservation could yield great economic benefits. [50]

The Master Plan addresses multiple strategies to achieve its goals. It seeks to improve its information management through the development of a database on climate change measures and the assessment of vulnerable areas on a local level. In terms of the forest cover itself, the plan suggests the prohibition of logging in protected areas, the reforestation of denuded watersheds, the planting of fast-growing indigenous species, and the strict enforcement of protection zones. The Master Plan also accounts for bushfire control through fire lines and firebreaks, and for and erosion control, sediment control, and soil conservation in unstable slopes. [51]

Limitations in biodiversity protection lie mainly in poor information management, including the absence of a central database management system, lack of data itself, poor communication within the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and ineffective information, education and communication (IEC) campaigns. [52]

The Master Plan covers multiple programs in great detail, including the Program to Strengthen Resilience of Forest Ecosystems and Communities to Climate Change, Programs to Respond to Demands for Forest Ecosystem Goods and Services, and Strategies to Promote Responsive Governance in the Forestry Sector. [53]

Regional and Local

The Region XI DENR focuses on managing natural resources sustainably and on implementing reforestation programs. [54] Among these, mangrove restoration projects are led by the Protected Areas and Biodiversity Conservation Program, [55] as outlined in the Davao Regional Plan. The region also supports the Enhanced National Greening Program and local community restoration efforts.

Protected Areas

As of now, there are 11 protected areas in the Davao Region. [56] The protected areas closest to Davao city are Mt. Apo Natural Park (550km2), Samal Island Protected Landscape and Seascape (162km2), and Malagos Watershed Reservation (2.3km2). [57]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (UN-REDD) operated in the Philippines from 2011 to 2013, focusing on fixing administrative issues and data management. [58]

Some nation-wide Philippine organizations operate locally in the Davao Region to protect endangered species. For instance, the Philippine Eagle Foundation operates in Mindanao to monitor Philippine Eagle population and lead captivity programs, including breeding and releasing. [59] The Philippine Raptors Conservation Program focuses on the rescue, retrieval, rehabilitation and release of injured birds, in cooperation with Regional Eagle Watch Teams. The group also conducts habitat management, monitoring, and research on effective release methods and movement patterns of juveniles. [60]

On a more local level, some community-based organizations like the Guardian Brotherhood lead volunteer programs linked to biodiversity conservation. [61] Local environmental conservation organizations include the Sustainable Davao Movement and the Interface Development Interventions (IDIS), which focus on tree planting, watershed conservation, and advocacy around urban expansion and loss of forest cover . [62] Further North in the Davao Gulf, the Tagum Trinity Project aims to restore 20ha of mangrove forest, 80ha of seagrass meadows and 20ha of coral reef habitat at the same time, to strengthen local ecosystems and protect them from degradation from waves. [63]

Public Awareness

Environmental awareness in the P hilippines is lar gely focused on climate change. Other than the conservation of a few charismatic species like the Philippine Eagle, a national symbol, biodiversity concerns are often tabled as limited resources are used to address urgent issues that pose a direct threat to human wellbeing, such as food insecurity and extreme poverty.

The country has two green parties: the Green Party of the Philippines (GP) and the Philippine Green Republican Party (PGRP). Neither part is currently represented in the Philippine congress.

In Davao specifically, local initiatives focus on replanting to combat climate change and on protecting watersheds to improve water quality. The continuation of practices harmful to habitats suggests that biodiversity conservation is not perceived as a necessity for sustainable development.

[3] CEPF. “Philippines.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/philippines.

[4] CEPF. “Philippines - Species | CEPF.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/philippines/species.

[5] “In the Aerie of the Philippine Eagle.” All About Birds, September 18, 2017. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/in-the-aerie-of-the-philippine-eagle/.

[6] CEPF. “Philippines - Species | CEPF.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/philippines/species.

[7] CEPF. “Philippines - Threats.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/philippines/threats.

[8] CEPF. “Philippines.” Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/philippines.

[9] WWF. “Southeastern Asia: Philippines | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0129.

[10] “Mindanao Bleeding-Heart.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 7, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[11] “Philippine Eagle.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 7, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[12] WWF. “Southeastern Asia: Philippines | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0129.

[13] “Mindanao-Eastern Visayas Rain Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/40129.

[14] WWF. “Mindanao Montane Rain Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0128.

[15] “Blue-Capped Kingfisher.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 7, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[16] “Philippine Warty Pig.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 7, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[17] “Philippine Deer.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 7, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[18] WWF. “Mindanao Montane Rain Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0128.

[19] “Mindanao Montane Rain Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/40128.

[20] BBC, “Philippines profile - Timeline,” http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-15581450, (accessed June 1, 2018)

[21] National Nutrition Council, “Region XI Profile,” http://www.nnc.gov.ph/regional-offices/region-xi-davao-region/55-region-11-profile (accessed June 18, 2018)

[22] Juliet C. Revita, “Davao City urged to strictly enforce proper waste management,” SunStar Philippines (November 20, 2017), http://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/405932/Davao-City-urged-to-strictly-enforce-proper-waste-management

Jennie Arado, “Implement waste management law in Davao, advocates urged,” SunStar Philippines (December 7, 2016), http://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/114132/Implement-waste-management-law-in-Davao-advocates-urged

Jun Ledesma, “Ledesma: Davao City Water District under threat,” SunStar Philippines (January 28, 2017)

http://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/123021/

[23] Biodiversity Management Bureau, “Profile: Mt. Apo Natural Park” http://www.bmb.gov.ph/images/bmbPDF/prof-mt._Apo.pdf (accessed June 1, 2018)

[24] Interface Development Interventions, “The Biodiversity of Davao’s Watersheds,” http://idisphil.org/2016/04/24/the-biodiversity-of-the-davaos-watersheds/ (accessed June 1, 2018)

[25] Regional Development Council, Davao Region, “Davao Region Physical Framework Plan 2015-2045,” 2015

[26] Philippine Statistics Authority, “Population of Davao City Reached 1.4 Million,” https://psa.gov.ph/content/population-davao-city-reached-14-million-results-2010-census-population-and-housing (accessed June 18, 2018)

[27] Karl Lester M Yap, “Strangled by Success, a Philippine Boomtown Expands Into the Sea,” Bloomberg , (December 21, 2015), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-12-21/strangled-by-success-a-philippine-boomtown-expands-into-the-sea

[28] Claudio Acioly Jr. and Junefe Gilig Payot, “Davao: building channels of participation and the land question, First Draft Report,” 2006

[29] Karl Lester M Yap, “Strangled by Success, a Philippine Boomtown Expands Into the Sea,” Bloomberg , (December 21, 2015), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-12-21/strangled-by-success-a-philippine-boomtown-expands-into-the-sea

[30] Henrylito D. Tacio, Region XI Department of Science and Technology, “Restoring Davao River Back to Life” (July 13, 2015), http://region11.dost.gov.ph/146-restoring-davao-river-back-to-life

[31] National Economic and Development Authority, Regional Development Committee, “Mindanao Spatial Strategy Development Framework 2015-2045,” 2015

[32] Department of Environment and Natural Resources, “Enhanced National Greening Program,” https://www.denr.gov.ph/priority-programs/national-greening-program.html (accessed June 1, 2018)

Philippine Biodiversity Management Bureau, “Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, 2015” Philippine Biodiversity Management Bureau, “Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, 2015,” 2015

[33] Philippine Forest Management Bureau, “Philippine Master Plan for Climate Resilient Forestry Development,” 2016

[34] National Economic and Development Authority, “Davao Regional Development Plan 2017-2022,” 2017

[35] National Economic and Development Authority, “Davao Regional Development Plan 2017-2022,” 2017

National Economic and Development Authority, “Davao Regional Development Plan 2017-2022,” 2017

Mindanao Development Authority, “Nurturing our Waters Program,” http://www.minda.gov.ph/project-management-and-coordination/nurturing-our-waters-now-program (accessed June 18, 2018)

MindaNow, “What we do,” http://now.minda.gov.ph/?page_id=18 (accessed June 1, 2018)

[36] National Economic and Development Authority, “Davao Regional Development Plan 2017-2022,” 2017

[37] Regional Development Council, Davao Region, “Davao Region Physical Framework Plan 2015-2045,” 2015

[38] Regional Development Council, Davao Region, “Davao Region Physical Framework Plan 2015-2045,” 2015

[39] Regional Development Council, Davao Region, “Davao Region Physical Framework Plan 2015-2045,” 2015

[40] Regional Development Council, Davao Region, “Davao Gulf Area Development Plan, 2011-2030,” 2011

[42] City Government of Davao, “Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance of Davao City,” 2013

[43] Foundation for the Philippine Environment “The Philippine Key Biodiversity Areas,” https://fpe.ph/biodiversity.html/view/the-philippine-key-biodiversity-areas-kbas (accessed June 18, 2018)

[44] Philippine Biodiversity Management Bureau, “Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, 2015,” 2015

Ryan Ponce Pacpaco, “House Okays Expanded NIPAS Act,” Journal Online (February 8, 2018)

http://www.journal.com.ph/news/nation/house-okays-expanded-nipas-act

[45] Philippine Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau, “Action Plan for Implementing the Convention of Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas,” 2012

[46] Philippine Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau, “Action Plan for Implementing the Convention of Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas,” 2012

[47] Philippine Biodiversity Managmeent Bureau, “Mission and Vision,” http://www.bmb.gov.ph/mainmenu-about-us/mainmenu-mission-and-vision (accessed June 1, 2018)

Protected Area Management Enhancement Project, “Project Objectives,” http://pame.denr.gov.ph/index.php/project-objectives (accessed June 1, 2018)

[48] Protected Area Management Enhancement Project, “Project Objectives,” http://pame.denr.gov.ph/index.php/project-objectives (accessed June 1, 2018)

[49] Philippine Biodiversity Management Bureau, “Report on the Management Effectiveness and Capacity Assessment of Protected Areas in the Philippines,” 2014

[50] Philippine Forest Management Bureau, “Philippine Master Plan for Climate Resilient Forestry Development,” 2016

[51] Philippine Forest Management Bureau, “Philippine Master Plan for Climate Resilient Forestry Development,” 2016

[52] Philippine Forest Management Bureau, “Philippine Master Plan for Climate Resilient Forestry Development,” 2016

[53] Philippine Forest Management Bureau, “Philippine Master Plan for Climate Resilient Forestry Development,” 2016

[54] City Environment and Natural Resources, “About us,” http://cenro.davaocity.gov.ph/?page_id=12#more-12 (accessed June 18, 2018)

Department of Environment and Natural Ressources, “Region XI Mandate, Mission and Vision” http://r11.denr.gov.ph/index.php/87-regional-articles-default/435-region-xi-mandate-mission-and-vision (accessed June 18, 2018)

[55] Department of Environment and Natural Ressources, “Protected Areas Management and Biodiversity Conservation Section,” http://r11.denr.gov.ph/index.php/pambcs-davao-compostella (accessed June 18, 2018)

[56] National Economic and Development Authority, “Davao Regional Development Plan 2017-2022,” 2017

Mindanao Development Authority, “Nurturing our Waters Program,” http://www.minda.gov.ph/project-management-and-coordination/nurturing-our-waters-now-program (accessed June 18, 2018)

[57] Regional Development Council, Davao Region, “Davao Region Physical Framework Plan 2015-2045,” 2015

[58] UN-REDD Programme, “The Philippines,” https://www.unredd.net/regions-and-countries/asia-pacific/philippines-the.html (accessed June 18, 2018)

[59] Philippine Eagle Foundation, “The Programs,” http://www.philippineeaglefoundation.org/programs (accessed June 18, 2018)

[60] Philippine Biodiversity Management Bureau, “Philippine Eagle Conservation,” http://bmb.gov.ph/384-protection-and-conservation-of-wildlife/programs/791-philippine-eagle-conservation (accessed June 1, 2018)

[61] Regional Development Council, Davao Region, “Region XI Nominees to the Search for Outstanding Volunteers (SOV) Receive Awards of Recognition” RDC XI Communicator (4th quarter, 2017) http://nro11.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/4q2017.pdf

[62] Interface Development Interventions, “2017 Annual Report,” 2017

[63] Henrylito D. Tacio, “Marine biologist-athlete rallies locals to save Davao Gulf’s ecosystem,” BusinessMirror (2018), https://businessmirror.com.ph/marine-biologist-athlete-rallies-locals-to-save-davao-gulfs-ecosystem/ (accessed June 1, 2018)