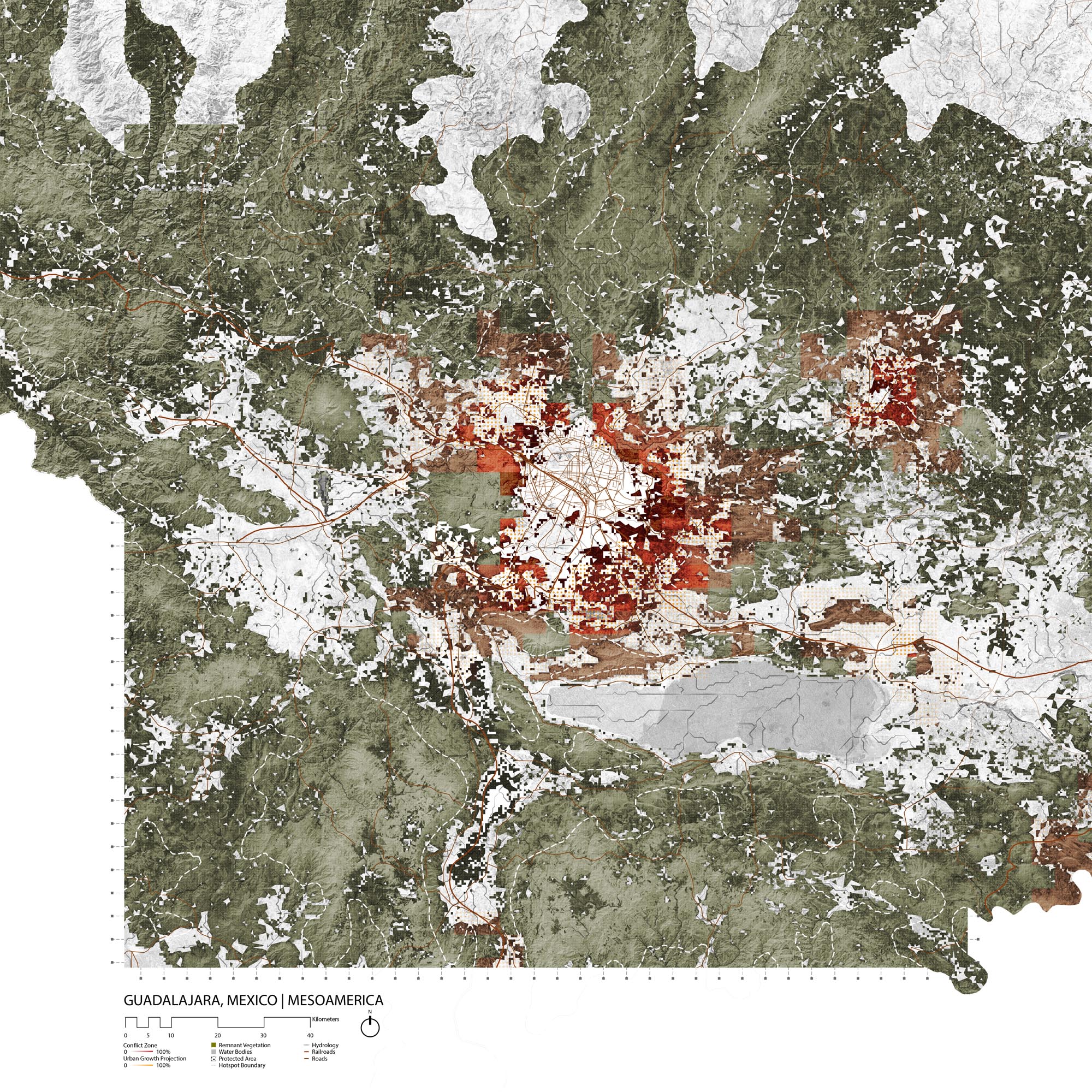

Guadalajara, Mexico

- Global Location plan: 20.66oN, 103.35oW [1]

- Hotspot:

- Population 2015: 4,843,000

- Projected population 2030: 5,837,000

- Endangered species:

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Agalychnis dacnicolor

- Rhinella marina

- Hypopachus ustus

- Incilius occidentalis

- Dryophytes eximius

- Smilisca fodiens

- Smilisca baudinii

- Craugastor augusti

- Craugastor hobartsmithi

- Eleutherodactylus nitidus

- Leptodactylus fragilis

- Lithobates psilonota

- Ambystoma velasci

- Dermophis oaxacae

- Smilisca dentata

- Spea multiplicata

- Hypopachus variolosus

- Ambystoma tigrinum

- Dryophytes arenicolor

- Trachycephalus typhonius

- Triprion spatulatus

- Leptodactylus melanonotus

- Incilius mazatlanensis

- Anaxyrus compactilis

- Incilius marmoreus

- Incilius perplexus

- Sarcohyla bistincta

- Exerodonta smaragdina

- Tlalocohyla smithii

- Eleutherodactylus angustidigitorum

- Eleutherodactylus modestus

- Craugastor occidentalis

- Eleutherodactylus pallidus

- Craugastor vocalis

- Lithobates forreri

- Lithobates megapoda

- Lithobates montezumae

- Lithobates neovolcanicus

- Lithobates pustulosus

- Lithobates zweifeli

- Ambystoma andersoni

- Ambystoma flavipiperatum

- Isthmura bellii

Mammals

- Otospermophilus variegatus

- Sylvilagus floridanus

- Eumops underwoodi

- Tadarida brasiliensis

- Myotis auriculus

- Myotis fortidens

- Nelsonia goldmani

- Pteronotus davyi

- Nyctinomops laticaudatus

- Peromyscus pectoralis

- Panthera onca

- Cratogeomys fumosus

- Peromyscus melanotis

- Peromyscus difficilis

- Peromyscus boylii

- Peromyscus levipes

- Reithrodontomys fulvescens

- Molossus sinaloae

- Reithrodontomys zacatecae

- Reithrodontomys microdon

- Microtus mexicanus

- Reithrodontomys sumichrasti

- Zygogeomys trichopus

- Baeodon alleni

- Baeodon gracilis

- Sorex saussurei

- Osgoodomys banderanus

- Lasiurus xanthinus

- Conepatus leuconotus

- Spilogale pygmaea

- Odocoileus virginianus

- Lasiurus cinereus

- Sciurus colliaei

- Sorex veraecrucis

- Sorex emarginatus

- Sorex orizabae

- Sturnira parvidens

- Sturnira hondurensis

- Hodomys alleni

- Sorex mediopua

- Leptonycteris yerbabuenae

- Nyctinomops macrotis

- Eumops ferox

- Promops centralis

- Peromyscus hylocetes

- Notiosorex evotis

- Micronycteris microtis

- Cynomops mexicanus

- Neotoma leucodon

- Spilogale angustifrons

- Baiomys musculus

- Peromyscus gratus

- Oryzomys couesi

- Heteromys irroratus

- Heteromys pictus

- Heteromys spectabilis

- Tlacuatzin canescens

- Glossophaga morenoi

- Neotoma mexicana

- Cryptotis alticola

- Peromyscus sagax

- Pecari tajacu

- Nasua narica

- Corynorhinus mexicanus

- Antrozous pallidus

- Cryptotis parva

- Mus musculus

- Saccopteryx bilineata

- Mormoops megalophylla

- Chaetodipus hispidus

- Diclidurus albus

- Thomomys umbrinus

- Lepus californicus

- Leptonycteris nivalis

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus

- Perognathus flavus

- Dipodomys ornatus

- Pappogeomys bulleri

- Pappogeomys bulleri

- Lasiurus intermedius

- Dasypus novemcinctus

- Herpailurus yagouaroundi

- Taxidea taxus

- Handleyomys melanotis

- Idionycteris phyllotis

- Myotis yumanensis

- Mephitis macroura

- Glossophaga commissarisi

- Puma concolor

- Reithrodontomys hirsutus

- Myotis velifer

- Notocitellus annulatus

- Sciurus aureogaster

- Dermanura azteca

- Lynx rufus

- Eira barbara

- Sigmodon mascotensis

- Glyphonycteris sylvestris

- Sigmodon fulviventer

- Sigmodon leucotis

- Neotoma palatina

- Neotomodon alstoni

- Bassariscus astutus

- Didelphis virginiana

- Peromyscus perfulvus

- Noctilio leporinus

- Dipodomys ordii

- Reithrodontomys chrysopsis

- Anoura geoffroyi

- Ictidomys mexicanus

- Natalus mexicanus

- Procyon lotor

- Molossus rufus

- Sylvilagus audubonii

- Megasorex gigas

- Notiosorex crawfordi

- Xerospermophilus spilosoma

- Orthogeomys grandis

- Myotis melanorhinus

- Canis latrans

- Lasiurus blossevillii

- Choeroniscus godmani

- Glaucomys volans

- Artibeus hirsutus

- Nyctinomops aurispinosus

- Myotis californicus

- Tamandua mexicana

- Eptesicus furinalis

- Balantiopteryx plicata

- Molossus aztecus

- Xenomys nelsoni

- Lepus callotis

- Myotis volans

- Bauerus dubiaquercus

- Enchisthenes hartii

- Artibeus lituratus

- Baiomys taylori

- Chaetodipus nelsoni

- Choeronycteris mexicana

- Oligoryzomys fulvescens

- Desmodus rotundus

- Eptesicus brasiliensis

- Eptesicus fuscus

- Eumops perotis

- Leopardus pardalis

- Lontra longicaudis

- Macrotus waterhousii

- Pteronotus personatus

- Molossus molossus

- Dermanura tolteca

- Myotis thysanodes

- Nyctinomops femorosaccus

- Nyctomys sumichrasti

- Dermanura phaeotis

- Pappogeomys bulleri ssp. alcorni

- Peromyscus maniculatus

- Peromyscus spicilegus

- Parastrellus hesperus

- Odocoileus hemionus

- Sigmodon alleni

- Artibeus jamaicensis

- Sorex oreopolus

- Sylvilagus cunicularius

- Chiroderma salvini

- Glossophaga soricina

- Peromyscus melanophrys

- Centurio senex

- Reithrodontomys megalotis

- Reithrodontomys mexicanus

- Leopardus wiedii

- Corynorhinus townsendii

- Rhogeessa parvula

- Mustela frenata

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

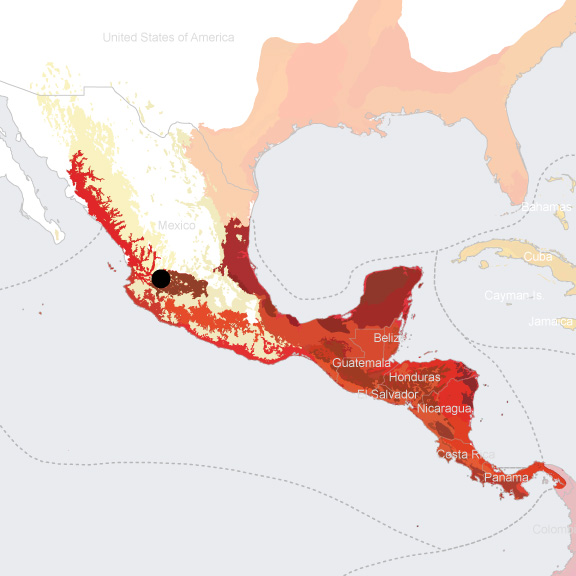

The Mesoamerica Biodiversity Hotspot encompasses all subtropical and tropical ecosystems from central Mexico to the Panama Canal. As North and South America were once two separate landmasses, the land bridge formed about 3 million years ago allowed the independently evolved flora and fauna to flow both ways and mingle. The north-south running mountain chains in turn facilitated isolation and speciation on both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts. They also harbor the highest montane forests of Central America, with the most extensive cloud forests. The hotspot moreover includes several islands in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, which are important for endemism, marine turtles, and seabirds. [2]

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~17,000 |

~3,000 |

- more than 300 cacti species |

|

Birds |

~1,120 |

>200 |

- resplendent quetzal ( Pharomachrus mocinno ), national emblem of Guatemala - 225 migratory species |

|

Mammals |

~440 |

>65 |

- endemism mostly attributed to small mammals - diverse in monkeys |

|

Reptiles |

>690 |

~240 |

- beach-nesting marine sea turtles |

|

Amphibians |

>550 |

>350 |

- rich in salamanders |

|

Freshwater Fishes |

>500 |

~350 |

|

In recent decades, the Mesoamerica hotspot has seen some of the highest deforestation rates in the world – averaging 1.4 percent annually between 1980 and 1990 – and most severe in El Salvador. It is estimated that 80 percent of the area’s original vegetation has been cleared or seriously altered. The main contributing factors to deforestation include the expanding road network, logging, agricultural encroachment, livestock production, and the use of wood for cooking. Even though there are new national parks and reserves, many of them are either too small or poorly protected in conflicting legal frameworks. Illegal traffic in timber and fauna is also a huge problem as law enforcement is weak in the region. [4]

The CEPF, having invested US$14.5 million in the hotspot from 2002 to 2011, had separate but complementary strategies for the northern and southern regions of Mesoamerica. In the north, the funds supported primarily the six Key Biodiversity Areas. In the south, CEPF focused on three priority landscapes in Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama. They promoted sustainable use of productive land, particularly through conservation coffee, ecotourism, agroforestry, and reforestation. [5]

Bajío Dry Forests

Guadalajara overlays three ecoregions—the Bajío Dry Forests, the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt Pine-oak Forests, and the Sinalon Dry Forests. The Bajío Dry Forests ecoregion sits in the western section of Mexico, consisting of valleys (1000-2000 m) interspersed with steep slopes and canyons. The climate is tropical sub-humid, with precipitation averaging 500 to 930 mm per annum, and a long dry season up to eight months. After many centuries of human use, the habitat is now a mosaic of urban settlements, forest patches, thorn scrubs, scattered marshes and lakes, and subtropical matorrals. Lake Chapala, Mexico’s largest freshwater lake, is especially rich in endemic ichthyofauna that is currently in danger of extinction. Even though part of the ecoregion is within the Central Mexican marshes Endemic Bird Area, little is known in terms of its biodiversity features otherwise. Agriculture, cattle and sheep grazing, and the textile industry have all been major reasons of forest destruction in the region. Mining is another serious issue, especially in Guanajuato. [6] At present, only 7 percent of the ecoregion is protected, and 3.63 percent terrestrially connected. [7]

Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt Pine-oak Forests

The Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt Pine-oak Forests ecoregion holds some of the most populated states in Mexico, including Mexico City. The unique active volcanic belt is the tallest and one of the only ranges in Mexico that runs from east to west, containing 13 of the highest peaks. Those mountains reach into the Arctic Zone and add more habitat diversity. The climate is temperate, and the level of humidity varies based on altitudes. The intense volcanic and orogenic activities have allowed the formation of abundant fluvial deposits, and the soil is strong in water retention. Pine forests grow at elevations of 2,275-2,600 m; pine-oaks at 2,470-2,600 m; and pine-cedars at over 2,700 m. The herbaceous stratum is also well developed and contains plentiful of epiphytes. [8]

Almost half of the total Mexican population lives along the Trans-Volcanic belt. Thus, forests have been cleared for agriculture, roads, and urban settlements. The traditional practice of burning the lower vegetation stratum for cattle is the most significant cause of deforestation – up to 80 percent of areas covered by pine-oaks are burned. Logging (especially for pine timber) is common. Such conditions also lead to intensified erosion. On the other hand, species are threatened due to selective exploitation. [9] Currently, 18 percent of the ecoregion is conserved within more than 70 protected areas, and has a 8.54 percent terrestrial connectivity. [10]

Sinaloan Dry Forests

The Sinaloan Dry Forests ecoregion hugs the northeastern edges of Guadalajara and constitutes the northernmost dry forests of Mexico. It shares some biodiversity with the Sonoran desert and the Sonoran-Sinaloan subtropical transition forests. [11] Today, 10 percent of the ecoregion is under protected and 5.13 percent is terrestrially connected. It has around a dozen protected areas. [12]

Environmental History

Before European conquests, the Guadalajara area was home to the Tecuexes and Coca tribes. When the city was first founded by merciless Spanish leader Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán, it was attacked on multiple occasions by natives in the area. [13] After relocating several times over the course of a decade, the city of Guadalajara was founded in 1542, in the midst of conflict between natives and Spaniards, especially slave hunters. As it developed, the city became the gateway that gave Spanish missions and expeditions access to the rest of the Mexican territory, and to lands as distant as the Philippines. [14] Spanish heritage is still visible in the city’s many late-renaissance, baroque, and neoclassical landmarks, including the Cathedral of the Assumption of Our Lady, completed in 1618. [15]

In addition to the early conflicts with natives, Guadalajara was caught in tensions of the 19th century. Indeed, in 1810, the city was seized by abolitionist and revolutionary leader Miguel Hidalgo, who came to be considered the father of the Mexican independence movement, despite his defeat shortly after. [16] In 1858, military and clergy men sparked a civil war after their title and land privileges were abolished. Guadalajara quickly fell into the liberal side, which ultimately won the war against conservatives. [17] At the end of the civil war, Napoleon III unsuccessfully tried to conquer Mexico, and his troops occupied Guadalajara during in 1864. [18]

After a century of wars, Guadalajara’s challenges shifted towards its development in the 20th century. Thus, the city’s first industrial park opened in 1947, marking the beginning of the electronic industry growth, which attracted immigrants from the rest of the country. [19] Guadalajara grew to become Mexico’s second biggest city by the 1970s. [20] Today, manufacturing is a driver of the city’s economy, although it has declined since the early 2000s due to Asian competition. The city’s production of electronics constitutes 60% of exports of the state of Jalisco, earning it the nickname of “Mexican Silicon Valley.” [21]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Guadalajara, as an expanding industrial city, is facing multiple pollution issues, namely worsening water and air pollution. [22] Indeed, hourly ozone levels and daily levels of 10-micron-particulate matter (PM10) are frequently higher than the the Mexican norm. [23]

In addition to its air pollution, the city has been faced with water management issue, specifically with the Chapala lake, which hosts highly endemic species and provides most of the city’s water. At the turn of 19th century, certain sides of the lake were artificially drained to avoid flooding risks and make way for more farmlands. The lake’s water is very polluted, and erosion due to deforestation has caused the accumulation of sediments. The lake’s temperature has also increased, and the proliferation of invasive species like water hyacinths poses a threat to native flora and fauna. The lake’s level reached its lowest volume in 2002, when it was only 14% full, returning to a steady 45% with heavy rain in the few years that followed. [24] The decentralization of water management towards a cooperative system and the state government’s efforts to improve wastewater management in the 1990s have helped protect the lake from further deteriorating. [25]

A 2002 study reveals that waste in Guadalajara was managed by a private company, which relied on partnerships with neighboring towns for disposal; the city of Guadalajara did not have any planning for waste management. The problem was only exacerbated by the low care for and awareness on environmental issues, as streets were regularly littered by citizens and collection services were unreliable, especially in lower-income areas. [26]

In more recent years, however, local government has shown sensibility for waste management, namely in a new Puntos limpios (“Clean Point”) system; public trash and recycling cans are connected to larger, underground storage spaces that do not need to be picked up as often. The government hopes to reduce expenses while improving the quality of services and promoting recycling. [27]

Although pollution and poor waste management certainly pose a problem for the environment in the Guadalajara area, the biggest direct threats to biodiversity are logging and wood collecting. The expansion of agricultural areas, cattle ranching, and commercial agriculture also pose a serious threat to local ecosystems. Biodiversity is furhter fragilized by mining , energy and infrastructure development, man-caused fires, and poor water management. It is relevant to note that poor forest restoration efforts also constitute a risk for the remaining natural cover. [28]

The urban expansion of Guadalajara has mainly occured in the northwest and South of the Guadalajara, since the city is contained by a canyon to the east and by a national park to the west. Development mainly took place in a grid-plan structure in suburban towns, which eventually grew to merge with the city of Guadalajara itself .

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Type of growth (formal informal, density): 10,361/km2; metro density: 1,583/km2;

Growth in Guadalajara is occurring mainly through the urbanization of rural areas and the movement of urban population to periurban countryside dwellings. The city does not have an urban growth boundary, and is sprawling outwards towards suburban towns, especially in the southwest. [29]

Between 1970 and 2000, ownership increased in the city due to federal policies, but the city grew more fragmented as lower-income communities were further excluded, despite increased social housing efforts. Indeed, Mexico has shifted its policies towards a market-oriented mindset, which has stimulated real estate developments and private ownership in Guadalajara. The deregulated market is causing some issues, especially land use conflicts or natural hazards. Gated communities are also expanding, using safety as their main selling point. Although the federal policies have caused a slight reduction in informal housing, it remains very prominent in the city, since half of developments between 1970 and 2000 were informal. [30]

Fraccionamientos also constitute a major portion of settlements in the Guadalajara area. They are typically large scale, tract-type housing schemes that are constructed in the suburbs, and often subsidized by public housing programs. Fraccionamientos seem like an overall an upgrade from informal settlements, but they still tend to be poorly serviced. In addition to directly contributing to urban sprawl, many fraccionamientos are located near environmentally hazardous sites, and are not always properly categorized as urban settlements by the local government. [31]

Although a few informal settlements existed in the city before 1972, they truly grew after that year, since 143 new settlements appeared by 1985 and another 155 by 1993. By 2000, informal settlements occupied 15% of the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area. [32] In order to provide a solution to informal settlements, the local government set up social housing schemes— stacked rows of suburban concrete homes that are criticized for being inaccessible and poorly serviced. [33] Thus, the city is now faced with the challenge of maintaining accessible formal ownership while supporting informal developments and reducing uncontrolled sprawl.

Governance

Guadalajara is the capital of the Centro region of Jalisco, one of the 31 states in Mexico. Jalisco is led by an elected governor. The city of Guadalajara extends beyond the administrative municipality of the same name, and onto seven neighboring municipalities, which constitute the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area . [34]

City Policy/Planning

Jalisco state has designed a partial development plan for the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area. The plan provides extensive zoning for five municipalities in addition to those of the Guadalajara municipality itself. [35]

The Plan Municipal de Desarrollo Guadalajara 500 sets a vision for the year 2042, when the city will celebrate is 500th anniversary. Among the its major objectives, the plan mentions the need to anticipate increased pollution and climate change, as well as to protect natural resources, and protect the balance of the environment. The second of nine principles that guide planning efforts is sustainability, explained as the ability to guaranty environmental stability to current and future generations. [36]

However, the plan focuses on pollution, climate change and environment-related health hazards, without any explicit mention of biodiversity. The document acknowledges a lack of environmental awareness, and the threats posed to the environment by inadequate settlement management. The document even recognizes the fragility of natural areas in the municipality and the problems that urban disorder poses to ecosystems, as well as the constant loss of animals and plant species. Urban forestation with endemic or adaptable species is mentioned as one of the twenty-two main suggestions received by the government on social media. The plan emphasizes the importance of inter-organizational cooperation, to facilitate efforts between the state, the federal government, and NGOs. [37]

The plan addresses to the need to promote a vertical model of expansion, and to improve the services provided by the city. However, sprawl itself does not seem to be of any concern to the government. [38]

A few design offices have put forward master plans for neighborhoods in the city. Among these, historic Guadalajara is to be redeveloped with the Ciudad Creative Digital project, designed by Carlo Ratti Associati and Dennis Frenchman. [39] Skidmore Owings & Merill have designed the master plan for an old Kodak manufacturing plant through a project called “Distrito de la Perla.” [40] The firm has also designed the first project within the district, the Bio-Esfera office, which is currently under construction. [41] Although these projects emphasize sustainability, they focus on energy efficiency rather than biodiversity conservation.

In its transportation planning, Guadalajara has sought inspiration in the way Bogota modified its own transportation system. Through multiple study visits to Bogota, Guadalajara has demonstrated a shift in its perception from looking up to Western designs to drawing inspiration from fellow southern cities. The project was initially led by Guadalajara 2020, a visioning group which has organized and funded study trips with the objective of creating a Bus Rapid Transit system in Guadalajara. [42]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Estrategia Nacional sobre Biodiversidad de México (ENBioMex) is guided by strategic axes informed by the Aichi convention and the UN millenium development goals, which are knowledge; conservation and restoration; sustainable use and management; attention to pressure factors; education, communication, culture; and mainstreaming and governance. [43]

The last axis is described by multiple actions, including the incorporation of biodiversity concerns into urban planning and infrastructure construction, and the improvement of ecosystem protection programs. It also mentions the importance of species monitoring and disease prevention. This section of the plan emphasizes the importance of protecting native ecosystems in cities and peri-urban areas. [44] The second strategic axis, on conservation and restoration, also mentions urban areas, especially the need to implement programs for the restoration of green areas in cities, particularly with native flora. More generally, this axis aims to expand the country’s protected area network, with an emphasis on connectivity and representativeness. In terms of ex-situ conservation, the document focuses on representativeness and genetic diversity of captive species. [45]

National

In Mexico, the Ministry of the Environment and of Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) is responsible for biodiversity conservation. [46] It is affiliated with the National Com mission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity, which focuses on funding multiple projects, especially academic research. [47] [48]

Regional

On the regional level, in 2017, the State of Jalisco elaborated a report on the state of Biodiversity in the region as well as a strategy for its conservation. The 800 pages of the Estudio de Estado (state study) are divided into two volumes; the first volume provides general information on the status of the area’s ecosystems and the second gives a detailed catalogue of its species and ecoregions. [49]

The first volume identifies the threats to ecosystems in Jalisco. Biodiversity is primarily threatened by population growth which, in the past 20 years, has caused the loss of 9% of the region’s natural cover and a 15% increase in its levels of surface water pollution, as well as increased consumptions of water, energy, and red meats. The document goes on to analyse land use changes between 1982 and 2007, namely the gain of nearly 10,000km2 of agricultural lands and of 2,500km2 of forests ( Bosques , which might refer to dry forests or to parks, it is not quite clear), and the loss of 8,800km2 of pastures and of 4,000km2 of forests ( selvas , which probably refers to rainforests/jungles). In addition to its expansion, agriculture has threatened ecosystems through unsustainable practices with the use chemica ls, which contribute to soil pollution. Sugar, tequila, tannery and food industries also tend to dispose their waste directly into bodies of water. Invasive species, including feral cats, feral dogs and plants, constitute the last main threat to local biodiversity, although the Estudio does underlines inefficient administration and poor effort coordination as major obstacles to conservation. [50]

In covering conservation and restoration in the region, the document further explains that only 43% of protected areas in Jalisco had a valid management plan, only a third onsite personnel, and only a third a management committee. Within protected areas, the biggest threats to biodiversity include real estate speculation ), protected area fragmentation, the alteration of hydrological processes, fires, and atmospheric pollution. The document identifies visitor activity, conversion for cattle grazing, urbanization and narcotics productions as secondary threats. This section also underlines the need for a central conservation system, with adequate policies and administration. [51] [52] [53]

The Estrategia para la Conservación y el Uso Sustentable de la Biodiversidad del estado de Jalisco (ECUSBIOJ) is structured by six strategies, which are each detailed with objectives and lines of action. The first strategy focuses on the creation and application of knowledge, namely the efficient use of technical labor and the utilization of traditional knowledge. The second strategy addresses conservation, restoration, and management, including the identification of priority biocultural regions and the conservation of specific endemic and threatened species. [54]

The third strategy focuses on sustainable land use practices and related incentives. It underlines the importance of interinstitutional cooperation and of integrating conservation efforts into politics. The strategy underlines the importance of involving the public with the help of compensations and incentives, through sustainable resource use and production practices, eco-certification, and traditional exploitation methods. [55]

The fourth strategy addresses pressure factors and threats, namely ecosystem degradation itself as well as alien invasive species, pollution, climate change and overexploitation practices. [56] The fifth strategy concerns environmental culture and education, including school education, awareness in society, and the diffusion of biodiversity values. Finally, the last strategy focuses on governance, legal framework and enforcement. Its lines of action include the creation of an “Articulating Instance” for the coordination of ECUSBIOJ, and the strengthening of municipal and intermunicipal management. [57]

Local

The city of Guadalajara does not have a department of the environment, and does not seem to have any biodiversity planning. [58]

Protected Areas Near City

Protected areas in the Guadalajara area are managed on three different levels. The only federal protected area in the region is the Primavera Flora and Fauna Protection Area, which is categorized as a level VI IUCN conservation area and covers 305km2. On a state level, the category VI Cerro Viejo-Chupinaya-Los Sabinos Protected Area is located further down south and covers 232km2, but protection is not strictly enforced in the parc, which is exposed to natural and man-made fires that clear forests for developments. [59] On a municipal level, the 177km2 Barranca del Rio Santiago corresponds to an IUCN level III reserve, but the 16km2 Bosque el Nixticuil San Esteban and the 91ha Bosque los Colomos are not categorized. [60]

Although protection is not systematically enforced, government efforts have led to the planting of 41,000 trees in the Primavera park, and local pressure has helped prevent further urbanization in Los Colomos. [61]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

There are many Mexican non-governmental organizations, but few of them operate in the Guadalajara area specifically. Among these, the Mexican Center of Environmental law tackles social and legal issues related to environmental protection and the Mexican Fund for the Conservation of Nature provides funds for endangered species protection, buffer-zone maintenance and to improve administrative processes, while also leading forest and watershed protection programmes. [62] [63] [64] Other country-wide organizations include Pro Natura, Naturalia, and Espacios naturales y desarollo sustenable which lead ecological restoration projects, raise awareness, or manage specific threatened species. [65] [66]

On a regional level, the Colectivo Ecologista is a Jalisciense organizations that focuses on education, advocacy, and awareness building, as well as applied research on biodiversity. [67] In Guadalajara proper, the Anillo Primavera organization is leading a project to create a buffer ring around the National Park to protect its natural heritage. [68]

Conclusion

Guadalajara is located at the intersection of three major Mexican ecoregions. This “magic circle” of biodiversity is also the second largest city in the country, and its attractiveness as a center for technological manufacturing is causing the uncontrolled expansion of its urban and rural areas. In a response to the alarming state of natural cover in all three ecoregions, the state of Jalisco has elaborated both a report on and a strategy and action plan for biodiversity in its area. The plan addresses all the major threats and obstacles to biodiversity conservation, including the land conversions caused by the growth of the state’s capital.

Aware of this growth and seeking modernization, the city of Guadalajara has formulated an extensive vision and plan for its development, including multiple initiatives that focus on pollution and health hazards. However, such planning barely mentions any concerns for biodiversity conservation, and does not seem to be alarmed by the city’s horizontal expansion.

Thus, despite evident awareness on biodiversity issues at some levels of regional government, city-level institutions do not seem to integrate conservation into their vision, begging the question of future urban development and its impact on already depleted ecosystems. The expansion and improved connection of protected areas are of utmost importance in all three ecoregions occupied by the Guadalajara metropolitan area, but such tasks cannot be carried out without first controlling sprawl.

[2] CEPF. “Mesoamerica.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mesoamerica.

[3] CEPF. “Mesoamerica - Species.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mesoamerica/species.

[4] CEPF. “Mesoamerica - Threats.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mesoamerica/threats.

[5] CEPF. “Mesoamerica.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mesoamerica.

[6] WWF. “Southern North America: Southern Mexico | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0204.

[7] “Bajío Dry Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60204.

[8] WWF. “Southern North America: Southern Mexico | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0310.

[9] WWF. “Southern North America: Southern Mexico | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0310.

[10] “Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt Pine-Oak Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60310.

[11] WWF. “Sinaloan Dry Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0228.

[12] “Sinaloan Dry Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60228.

[13] Donna S. Morales & John P. Schmal, The Hispanic Experience Cultural Heritage, “The History of Jalisco” (2004), http://www.houstonculture.org/hispanic/jalisco.html

[14] Encyclopedia Britannica, “Guadalajara,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Guadalajara-Mexico (accessed July 31, 2018)

Lonely Planet, “History of Guadalajara,” https://www.lonelyplanet.com/mexico/western-central-highlands/guadalajara/history (accessed July 31, 2018)

[15] Lonely Planet, “Catedral de Guadelajara,” https://www.lonelyplanet.com/mexico/guadalajara/attractions/catedral-de-guadalajara/a/poi-sig/433600/361671 (accessed July 31, 2018).

[16] “Guadelajara, victoria y derrota de Miguel Hidalgo,” Informador (January 10, 2010), https://www.informador.mx/Cultura/Guadalajara-victoria-y-derrota-de-Miguel-Hidalgo-20100110-0207.html

[17] Encyclopedia Britanica, “La Reforma,” https://www.britannica.com/event/La-Reforma (accessed July 31, 2018)

[18] World Guides, “Guadalajara History Facts and Timeline,” http://www.world-guides.com/north-america/mexico/jalisco/guadalajara/guadalajara_history.html (accessed July 31, 2018)

Encyclopedia Britanica, “La Reforma,” https://www.britannica.com/event/La-Reforma (accessed July 31, 2018)

[19] World Guides, “Guadalajara History Facts and Timeline,” http://www.world-guides.com/north-america/mexico/jalisco/guadalajara/guadalajara_history.html (accessed July 31, 2018

[20] Encyclopedia Britannica, “Guadalajara,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Guadalajara-Mexico (accessed July 31, 2018)

Lonely Planet, “History of Guadalajara,” https://www.lonelyplanet.com/mexico/western-central-highlands/guadalajara/history (accessed July 31, 2018)

[21] The Offshore Group, “Guadalajara: A prime economy for manufacturing in Mexico” (January 29, 2016), https://insights.offshoregroup.com/guadalajara-a-prime-economy-for-manufacturing-in-mexico

[22] Numbeo, “Pollution in Guadalajara, Mexico,” https://www.numbeo.com/pollution/in/Guadalajara (accessed July 31, 2018)

[23] Mariam Fonseca-Hernández et al., “Atmospheric Pollution by PM10 and O3 in the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area, Mexico,” Atmosphere 9: 7 (June 26, 2018).

[24] Todd Stong, “Will Guadalajara Save Lake Chapala Again?,” The Guadalajara Reporter (April 5, 2013), https://theguadalajarareporter.net/index.php/news/news/lake-chapala/41887-will-guadalajara-save-lake-chapala-again

[25] Etienne von Bertrab, “Guadalajara’s water crisis and the fate of Lake Chapala: a reflection of poor water management in Mexico,” Environment & Urbanization 15:2 (October 2003).

[26] Gerardo Bernache, “The environmental impact of municipal waste management: the case of Guadalajara metro area,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 39:3 (October 2003).

[27] “Guadalajara unveils its new garbage system Containers” Mexico News Daily (April 13, 2016)

https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/guadalajara-unveils-its-new-garbage-system/

[28] Organization fo American States, “Biodiversity threats, Guadalajara,” http://www.oas.org/en/sedi/dsd/Biodiversity/WHMSI/Presentations/Guadalajara/Threats.pdf (accessed July 31, 2018)

[29] Geo-Mexico, “Population change in the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area” http://geo-mexico.com/?p=3395 (accessed July 31, 2018)

[30] John Harner, Edith Rosario Jimenez Huerta, Heriberto Cruz Solís, “Buying Development: Housing and Urban Growth in Guadalajara, Mexico,” Urban Geography 30: 5 (July 2009).

[31] Yu Chen, “What is Unique about Fraccionamientos?,” 108th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, New York (2013), https://soa.utexas.edu/sites/default/disk/Yu.pdf

[32] Adriana Fausto Brito et al. “Metodología para identificar los asentamientos de origen irregular consolidados en Guadalajara” ( seems unpublished? )

[33] Adriana Fausto Brito, Latin American Housing Network, “Problemas de vivienda en el área metropolitana de Guadalajara,” http://www.gdl.cinvestav.mx/ofelia/uploads/presentacionesJJC2010/Dra_Fausto_Urbanismo_JJC2010.pdf (accessed July 31, 2018).

[34] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen I” (2017).

[35] Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano, “Planes Parciales de Desarollo Urbano de Los Municipios de la Zona Metropolitana de Guadalajara,” http://sedeur.app.jalisco.gob.mx/zona-conurbada/inicio.html (accessed July 31, 2018)

[36] Gobierno de Guadalajara, “Plan Municipal de Desarollo Guadalajara 500/ Vision 2042” (2016).

[37] Gobierno de Guadalajara, “Plan Municipal de Desarollo Guadalajara 500/ Vision 2042” (2016), 34, 97, 98, 101

[38] Gobierno de Guadalajara, “Plan Municipal de Desarollo Guadalajara 500/ Vision 2042” (2016)

[39] Ciudad Creativa Digital, “What is CCD?,” http://ccdguadalajara.com/en_US/ (accessed July 31, 2018)

carlorattiassociati et al., “Plan Maestro de Guadalajara - Ciudad Creativa Digital” (November 2012), http://ccdguadalajara.com/en_US/plan-maestro/.

[40] SOM, “Distrito La Perla Master Plan,” https://www.som.com/projects/distrito_la_perla_master_plan (accessed July 31, 2018).

[41] SOM, “Bio-esfera,” https://www.som.com/projects/bio-esfera (accessed July 31, 2018).

[42] Sergio Montero, “Study tours and inter-city policy learning: Mobilizing Bogotá’s transportation policies in Guadalajara,” Environment and Planning A 49, no. 2 (2017): 332.

[43] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “Estrategia Nacional sobre Biodiversidad de México y Plan de Acción 2016-2030” (2016).

[44] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “Estrategia Nacional sobre Biodiversidad de México y Plan de Acción 2016-2030” (2016).

[45] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “Estrategia Nacional sobre Biodiversidad de México y Plan de Acción 2016-2030” (2016).

[46] Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, “Acciones y programas,” https://www.gob.mx/semarnat#367 (accessed July 31, 2018).

[47] Biodiversidad Mexicana, “Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y uso de la Biodiversidad,” https://www.gob.mx/conabio/acciones-y-programas/proyectos-56730 (accessed July 31, 2018)

[48] Biodiversidad Mexicana, “Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y uso de la Biodiversidad,” https://www.gob.mx/conabio/acciones-y-programas/proyectos-56730 (accessed July 31, 2018)

[49] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen I” (2017).

Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen II” (2017).

[50] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen I” (2017).

[51] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen I” (2017).

[52] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen I” (2017).

[53] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen I” (2017).

[54] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “Estrategia para la Conservacion y el Uso Sustenable de la Biodiversidad del estado de Jalisco” (2017).

[55] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “Estrategia para la Conservacion y el Uso Sustenable de la Biodiversidad del estado de Jalisco” (2017).

[56] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “Estrategia para la Conservacion y el Uso Sustenable de la Biodiversidad del estado de Jalisco” (2017).

[57] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “Estrategia para la Conservacion y el Uso Sustenable de la Biodiversidad del estado de Jalisco” (2017).

[58] Ciudapp, “Coordinaciones,” https://guadalajara.gob.mx/coordinacion-dependencias (accessed July 31, 2018).

[59] “El Área Natural Protegida ‘Cerro Viejo, Chupinaya, los Sabinos’ sigue sin ser protegida,” Laguna (June 20, 2017), http://semanariolaguna.com/28690/

[60] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen I” (2017).

[61] Mexico, “Cities with Biodiversity: Lots More Than Pets” (December 15, 2016), https://www.mexico.mx/en/articles/cities-with-biodiversity-lots-more-than-pets.

[62] CEMDA, “Objectivos,” http://www.cemda.org.mx/objetivos/ (accessed July 31, 2018)

[63] Fondo Mexicano para la Conservación de la Naturaleza, “Areas Naturales Protegidas,” https://fmcn.org/areas-protegidas/ (accessed July 31, 2018)

[64] Fondo Mexicano para la Conservación de la Naturaleza, “Programa de Conservación de Bosques y Cuencas” https://fmcn.org/bosques-y-cuencas/ (accessed July 31, 2018)

[65] Pro Natura, “Quiénes somos,” http://www.pronatura.org.mx/ (accessed July 31, 2018)

[66] Naturalia, “Quiénes somos,” http://www.naturalia.org.mx/ (accessed July 31, 2018)

[67] Colectivo Ecologista Jalisco, “Quiénes somos,” http://www.cej.org.mx/ (accessed July 31, 2018)

[68] Mexico, “5 Mexican Organizations That Embrace Our Woodlands” (Decemeber 8, 2016), https://www.mexico.mx/en/articles/5-mexican-organizations-that-embrace-our-woodlands.

[69] Jo Tuckman, “Mexico's Greens: pro-death penalty, allegedly corrupt – and not very green,” The Guardian (April 21, 2015), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/21/mexico-green-party-corruption-claims-environment.

[70] Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, “La Biodiversidad en Jalisco, Estudio de Estado, Volumen I” (2017).