Guangzhou, China

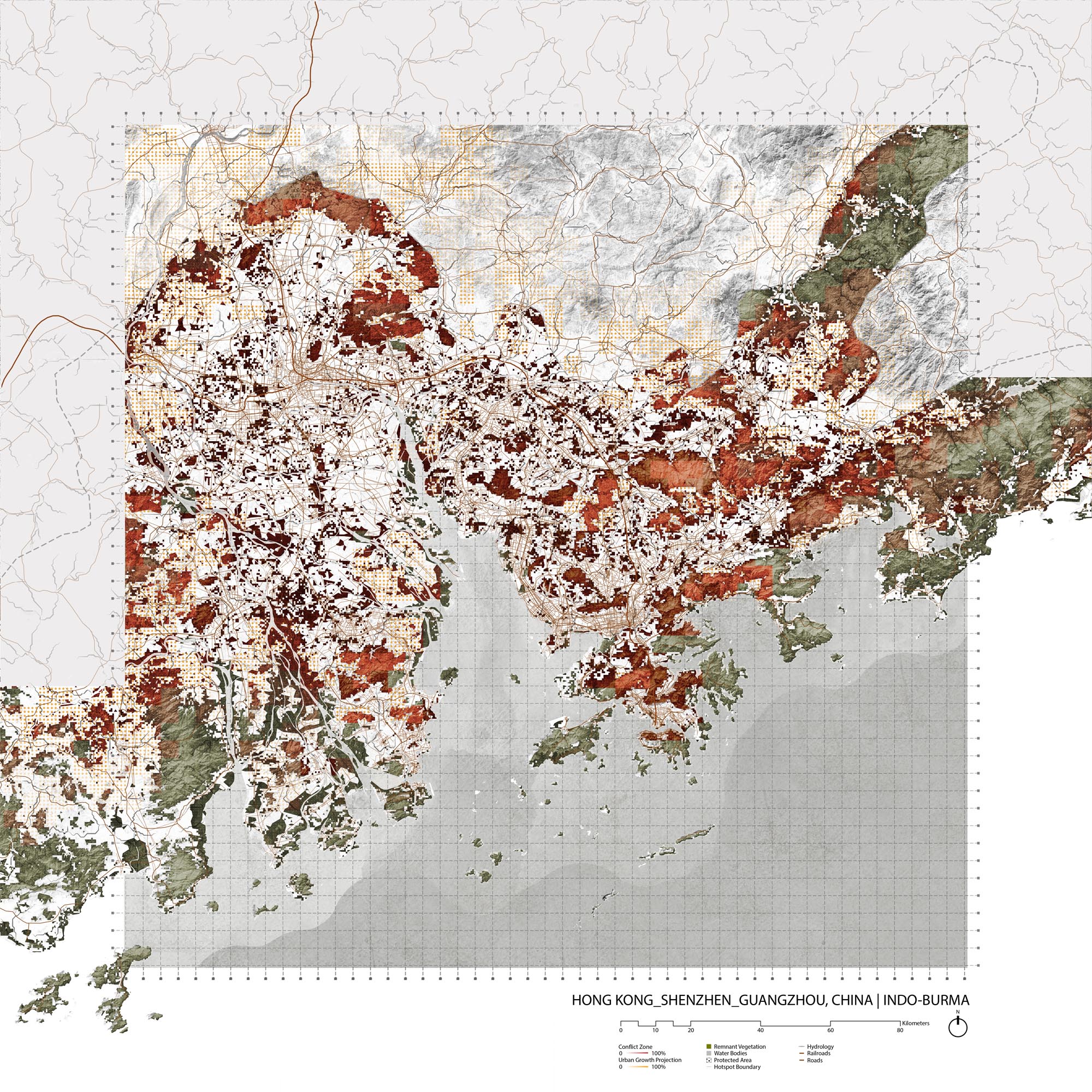

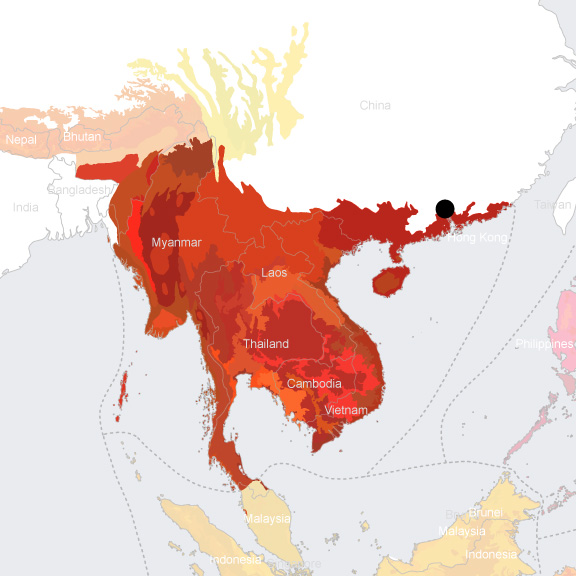

- Global Location plan: 23.13oN, 113.26oE [1]

- Hotspot: Indo-Burma

- Population 2015: 12,458,000

- Projected population 2030: 17,574,000

- Mascot Species: Pangolin (Manis pentadactyla)

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Kurixalus odontotarsus

- Hylarana macrodactyla

- Amolops ricketti

- Microhyla heymonsi

- Hoplobatrachus rugulosus

- Babina adenopleura

- Leptobrachium liui

- Megophrys mangshanensis

- Kaloula pulchra

- Microhyla butleri

- Microhyla pulchra

- Fejervarya limnocharis

- Occidozyga martensii

- Quasipaa exilispinosa

- Hylarana latouchii

- Odorrana versabilis

- Rana zhenhaiensis

- Liuixalus romeri

- Hypselotriton orphicus

- Paramesotriton chinensis

- Paramesotriton hongkongensis

- Kalophrynus interlineatus

- Odorrana chloronota

- Megophrys microstoma

- Rhacophorus dennysi

- Quasipaa spinosa

- Polypedates megacephalus

- Duttaphrynus melanostictus

- Hyla simplex

- Liuixalus romeri

- Pachytriton brevipes

- Bufo cryptotympanicus

- Microhyla fissipes

- Hyla sanchiangensis

- Hylarana taipehensis

- Occidozyga lima

- Megophrys brachykolos

- Megophrys kuatunensis

- Amolops hongkongensis

- Fejervarya multistriata

- Limnonectes fujianensis

- Sylvirana cubitalis

- Sylvirana guentheri

- Odorrana margaretae

- Odorrana schmackeri

- Liuixalus romeri

- Pachytriton labiatus

- Ichthyophis bannanicus

- Leptobrachella liui

Mammals

- Myotis frater

- Typhlomys cinereus

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Mesoplodon ginkgodens

- Miniopterus pusillus

- Pipistrellus pulveratus

- Prionailurus bengalensis

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Rhinolophus affinis

- Martes flavigula

- Rhinolophus rex

- Melogale personata

- Mustela kathiah

- Rusa unicolor

- Rattus nitidus

- Nyctalus plancyi

- Muntiacus vaginalis

- Balaenoptera omurai

- Rhinolophus shortridgei

- Berylmys bowersi

- Miniopterus magnater

- Eptesicus pachyomus

- Peponocephala electra

- Sus scrofa

- Tursiops truncatus

- Tursiops aduncus

- Rattus rattus

- Taphozous melanopogon

- Panthera pardus ssp. delacouri

- Stenella longirostris

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Herpestes javanicus

- Manis pentadactyla

- Vespertilio sinensis

- Myotis pilosus

- Rhinolophus pusillus

- Rhinolophus luctus

- Scotophilus kuhlii

- Panthera pardus

- Panthera pardus

- Hipposideros pratti

- Myotis horsfieldii

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Cynopterus brachyotis

- Pipistrellus abramus

- Rhinolophus siamensis

- Myotis horsfieldii

- Rhinolophus sinicus

- Myotis fimbriatus

- Aonyx cinereus

- Myotis chinensis

- Myotis indochinensis

- Myotis altarium

- Myotis chinensis

- Rhinolophus pearsonii

- Scotophilus heathii

- Myotis davidii

- Myotis laniger

- Kerivoula titania

- Harpiocephalus harpia

- Macaca mulatta

- Mus musculus

- Moschus berezovskii

- Macaca thibetana

- Chimarrogale himalayica

- Grampus griseus

- Chaerephon plicatus

- Arctonyx albogularis

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Ursus thibetanus

- Murina leucogaster

- Orcinus orca

- Petaurista philippensis

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Sousa chinensis

- Viverra zibetha

- Herpestes urva

- Muntiacus reevesi

- Arctonyx albogularis

- Lepus sinensis

- Lutra lutra

- Hipposideros armiger

- Rhizomys pruinosus

- Leopoldamys edwardsi

- Rousettus leschenaultii

- Tamiops maritimus

- Tylonycteris pachypus

- Lagenodelphis hosei

- Crocidura attenuata

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Melogale moschata

- Rhizomys sinensis

- Rattus andamanensis

- Paguma larvata

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Vulpes vulpes

- Delphinus capensis

- Paradoxurus hermaphroditus

- Rattus losea

- Indopacetus pacificus

- Suncus murinus

- Prionodon pardicolor

- Muntiacus reevesi

- Neophocaena phocaenoides

- Capricornis milneedwardsii

- Scotomanes ornatus

- Naemorhedus griseus

- Rattus tanezumi

- Hystrix brachyura

- Stenella attenuata

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Nyctereutes procyonoides

- Hipposideros armiger

- Kogia sima

- Macaca arctoides

- Macaca arctoides

- Micromys minutus

- Mus caroli

- Rhinolophus affinis

- Callosciurus erythraeus

- Eschrichtius robustus

- Mustela sibirica

- Feresa attenuata

- Kerivoula picta

- Pipistrellus pulveratus

- Macaca mulatta

- Viverricula indica

- Niviventer confucianus

- Bandicota indica

- Bandicota indica

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Balaenoptera physalus

- Pipistrellus pipistrellus

- Kogia breviceps

- Ursus thibetanus

- Neofelis nebulosa

- Hipposideros pomona

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Eptesicus serotinus

- Niviventer fulvescens

- Herpestes urva

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot comprises all non-marine parts of Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, plus parts of southern China. Apart from being one of the most biologically vital areas of the planet, it supports a population of over 300 million people, the largest amongst all hotspots. [2]

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~20,000 |

~50% |

- 40 percent of all threatened species in the hotspot - many narrowly endemic orchids |

|

Birds |

>1,200 |

DD |

- significant amount of migratory species |

|

Mammals |

>400 |

DD |

- concentration of threatened primates (20 endemic species) - Vulnerable Pygmy slow loris ( Nycticebus pygmaeus ) [4] , Critically Endangered Delacour's langur ( Trachypithecus delacouri ) [5] , both of which the range overlaps or nears the city of Hanoi |

|

Reptiles |

>500 |

>25% |

- richest non-marine turtle fauna in the world |

|

Amphibians |

>300 |

~50% |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

~270 |

30 |

|

|

Invertebrates |

DD |

DD |

|

The rapid economic development and increasing human population are exerting enormous pressure on Indo-Burma’s natural resources. Major sources of threat include hunting, wildlife trade, transportation infrastructure, and logging (especially in Cambodia and Lao PDR). In terms of agriculture, industrial plantations of perennial cash crops (such as eucalypts, rubber, pine, tea, coffee, and oil palm) are replacing original forests. In addition, the rising demand for flood control, irrigation, and electricity generation is fueling a wave of new dam constructions. [6]

Jian Nan Subtropical Evergreen Forests

Guangzhou is primarily located in the South China-Vietnam Subtropical Evergreen Forests ecoregion, but the city’s periphery extends into the Jian Nan subtropical evergreen forests ecoregion. [7] The Chinese portion of the former ecoregion runs along the coast and does not have any protected areas. [8] The Jian Nan Subtropical Evergreen Forests ecoregion includes the extensive hills to the south of the lower Yangtze River Basin and north of the tropical coastal plains of southeastern China. The granitic Nanling Mountain Range is a major landscape feature, with elevations from 500 to 1,500 m. The precipitation patterns are typhoon-dominated in the summer. The range is dominated by chestnut and other plants of the oak family, with Shima spp ., a member of the tea family ( Theaceae spp .) and various laurels ( Lauraceae spp .) as important associates. The area is also rich in birds, including migratory passerine species. [9]

Most of the original native vegetation has been extirpated. Exceptions are on inaccessible steep hillsides, particularly in limestone areas poorly suited to agriculture. Land conversion to rice paddy has been in practice for centuries, and more recently also to plantations of conifers. Hunting and collection of rare species for sale are significant threats as well. [10] At present, there are only three protected areas – all World Heritage Sites – in mainland China in the ecoregion. The percentages of protection area and terrestrial connectivity are both below one. [11]

Environmental History

Occupied since approximately 5000 BCE, the area where Guangzhou stands today was chosen to be the capital of the Nanhai prefecture by the first Chinese emperor Qin Shi Hang. It developed into a merchant town with the arrival of Arab, Indian and Persian merchants in the early 7th century. The Portuguese gained a trade monopoly of the area in 1511. By the 17th century, the British, Dutch and French powers also engaged in trade with Guangzhou, attracted by such coveted products as tea, porcelain and silk. The city gained even more power when all Chinese foreign trade was restricted to Guangzhou. [12]

Yet, the city was also a place of tensions, as the British started importing Indian opium through its ports, causing social problems throughout China and finally causing the Opium war and the 1842 occupation of Hong Kong by the British following the treaty of Nanjing.

Guangzhou was also a place of uprising. In the 1850s, Hong Xiu Quan started the Tai Ping Rebellion against the Qing. Later, Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Chinese Nationalist Party, made multiple failed coup attempts and sparked protests that ultimately resulted in the creation of the Republic of China in 1911. After protests against foreign occupation in the 1920s, and some industrial development in the 1930s, the city was occupied by Japan from 1938 until the end of World War II. Guangzhou was then occupied by the Jiand Jie Shi Nationalist forces until the communist troops of Lin Biao took the city in 1949. [13]

Due to its vulnerability, the city was largely ignored by Mao, but started successfully developing under the economic reforms of Deng Xiao Ping in the 1970s and 1980s. [14]

Starting in 1950, the area mostly produced electronics, textiles, newsprint, processed foods, and firecrackers. Local production expanded to include heavier industries, such as machinery, chemicals, iron and steel, cement, ships, and automobiles. Most investments since the 1970s have been made by foreigners who are based in neighboring Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan.

Handicraft objects like ivory and jade objects, or embroideries, are also important to the local economy, as is tourism. To this day, Guangzhou remains an important center for trade, traditionally for commodities like sugar, silk, timber, tea, and herbs, and since the 1980s for manufactured goods and mechanical or electronic equipment. [15]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

The city of Guangzhou has been fighting against pollution for many years, reaching some levels of success, namely with atmospheric pollution. Indeed, the city’s PM2.5 levels dropped by 42% between 2012 and 2016, reaching a level of 39μg/m3, which remains above the WHO’s recommended limit of 35μg/m3. Additionally, the government’s apparent transparency on pollution data suggests genuine efforts on its part to combat pollution. [16] The local government also states that sulphur dioxide levels fell by 84% between 2012 and 2016. Initiatives like the replacement of all buses and taxis with electric vehicles further suggest that atmospheric pollution is effectively being fought in the city. [17]

Guangzhou’s waste management is also being improved, with a strict garbage collection system that charges citizens for collection, limiting the supply of complementary trash bags per household. With this system, the government is hoping to reduce waste production in the city. [18]

Since 2010, wastewater management has reportedly improved as well. At that time, urbanization was causing high water pollution levels, due to population growth and industrial activities. [19] Indeed, some sources describe an improved situation in 2017, thanks to the government shutting down harmful factories, planning sewage pipes, and leading riverbank greening projects. [20] However, other sources explain that the city only constructed a third of the planned sewage pipes, and that many waterways in Guangzhou remained terribly polluted with sewage. [21]

The city is surrounded by large, yet somewhat fragmented areas of natural vegetation that occupy upperlands while settlements and transportations axes take up the valleys. Interestingly, urban areas do not seem to have encroached upon woodlands as much as on agriculture areas. Indeed, satellite imaging reveals that from 1986 to 2016, large areas of rural land were converted to urban settlements, but remaining forest cover was mostly left intact. Urban expansion became dramatic after 2000, when the multiple cities that occupy the delta, though initially rather small and separated by farmlands, grew to merge into a megacity which now occupies the near-totality of cultivated land in the area. Thus, urban sprawl does not seem like it has posed a direct threat to forest cover, since it is contained by the limits of the original farmlands of the delta. However, the extraordinary growth of the city’s population certainly increases the pressures on existing ecosystems, in addition to fragmenting the forest cover .

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

In 2017, the city of Guangzhou had an official population of 8.98 million, but the the Pearl river delta had a population of nearly 109 million in 2015. [22] Between 1980 and 2004, the Guangdong population from 57 to 83 inhabitants. During this time period, the fastest growing municipality was Shenzen, which grew from 320,000 to 1,650,000 people, followed by Zhuhai, which grew from 370,000 to 860,000 people. In 2004, Guangzhou was the most populated municipality, followed by Hong Kong, Zhaoqing and Jiangmen, with respectively 7.4, 6.9, 3.94, and 3.86 million people. [23]

Within the administrative city of Guangzhou, growth occurred in multiple stages, starting with urban expansion around old city districts with spontaneous growth in the suburbs between 1979 and 1990. In the following decade, the expansion progressed along important transportation axes, initiating the expansion of the existing urban boundary with sprawl. Finally, in the 2000s, infilling growth was the main type of expansion, with the decline of edge-expansion, until 2009, when the latter became prominent again. [24] Today, the driving factors of urban growth in Guangzhou are economic growth, urban population, and transportation development. [25]

Though formal development constitutes the majority of urban growth in Guangzhou, informal settlements exist in the form of chengzhongcun (urban villages), which local governments generally try to destruct. [26] An estimated 277 urban villages currently exist in Guangzhou, but their informal nature should not be misunderstood for slum-like conditions—rather, the villages result from the expansion of settlements that predate urban development, whose inhabitants typically live in private, informal rentals instead of self-constructed dwellings. Urban villages are typically described negatively by the government which tries to justify demolishing them to make way for development projects. However, urban villages do not all lack essential services, and their dwellers are not all unsatisfied with their situation. [27]

Governance

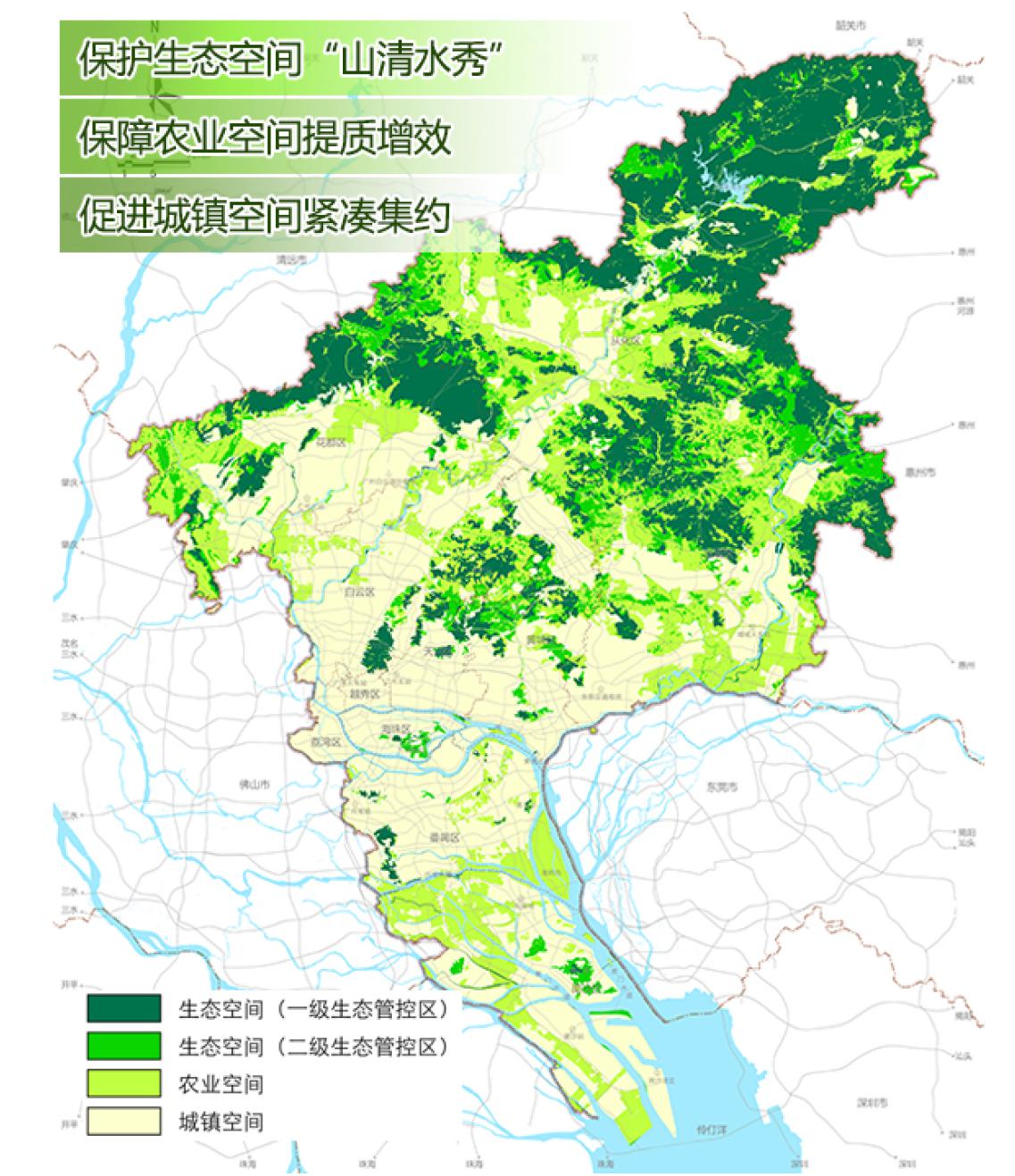

As a sub-provincial city, Guangzhou has a significant amount of autonomy from its province, Guangdong. [29] National ministries still exert considerable pressure on the city’s planning efforts, as evidenced by a 2015 order from the Chinese Ministry of Land and Resources that Guangzhou, along with 13 other cities, restore or preserve its greenbelts. [30]

The city government structure is an extension of the country’s administration, controlled by both the government and the party. The administrative authority in Guangzhou is held by the Guangzhou Municipal People’s Congress, and the executive power rests with People’s Government of Guangzhou Municipality whose mayors and officials are elected by the congress. [31]

The metropolitan area of the pearl river delta extends beyond Guangzhou; the megacity also includes the cities of Foshan, Donguan, Zhongshan, Jiangmen, Zhaoqing, Quinyan, Huizhou and Shenzen, in addition to Macau and Hong Kong.

City Policy/Planning

Provincial

Guangzhou only represents a portion of the Pearl River Delta metropolitan area, whose planning is split between multiple municipalities. The national government is expected to release a development plan for the larger Delta area, which will include Hong Kong and Macau. [34] Currently, provincial development falls under the jurisdiction of the Guangdong Provincial Development and Reform Commission. [35] The Commission created the 2009-2020 Pearl River Delta Urban and Rural Planning Integration Plan, but it did not include the two Special Administrative Regions. [36]

The document does not provide a spatial development plan, but rather suggestions and targets to guide the growth of the city. The plan acknowledges the rapid rate of urban construction, and the outwards expansion of the city. However, it does seem make combating urban sprawl a priority. The plan shows some concern for environmental issues, with the target of increasing its green areas to cover 35% of the region’s surface by 2020. [37]

Local

The Guangzhou Plan for National Economic and Social Development was approved by China’s central government in 2016, and sets targets for the year 2020. [38] Among other things, the city plans to develop a free trade zone in its Nansha district, and to improve transportation and connectivity between the different cities in the area, especially Hong Kong and Macau. [39]

Between 1947 and 2017, Guangzhou has had multiple master plans, which were initially geared towards economic development and rapid urbanization. As the city grew, the plans focused on channelling growth further away from the urban core and into satellite cities, to keep the city more manageable. With the start of new millenium, planning was discussed on a more regional level, utilizing input from multiple local universities.

The latest of these master plans is a 2017 draft of the Guangzhou City Master Plan that sets targets for 2035, with the objective of developing a “beautiful liveable city” and a “vibrant global city.” By 2025, the plan aims for Guangzhou to be a high-quality, powerful, affluent city that is charming and green. By 2035, the city is to become a pioneer of socialist modernization that is economically, scientifically, and technologically strong, as liveable as as many world-class cities. By 2050, Guangzhou should be a prosperous Chinese global city that is to showcase the success of Chinese socialist modernization to the world. [40]

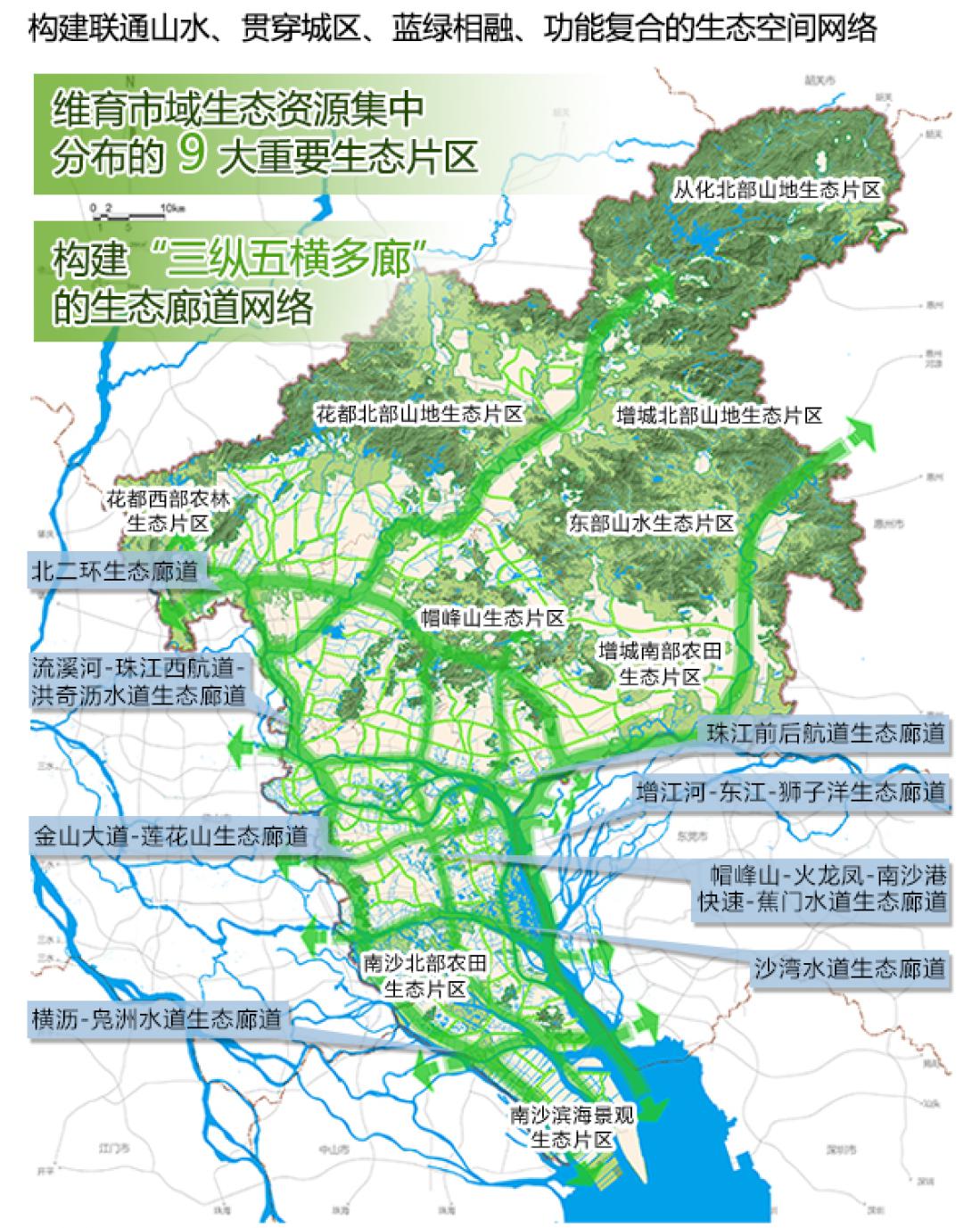

The Master Plan provides some level of zoning for the city and specific development intentions for areas like the Pearl River Landscape Belt, which includes a business district. The plan also shows and some consideration of ecological spaces. Indeed, the plan describes ecological protection zones, and includes plans to increase green areas in the city, to improve ecological corridors. The document also describes the objective of protecting over 1300 rivers in the city to facilitate ecological restoration and form an urban water network that can effectively be managed. [41]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

According to the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan of China, the country’s current reserves cover an area of 1.49 million km2, aka 15% of the nation’s surface. Yet, industrialization and urbanization continue to threaten Chinese habitats. The Plan is structured by goals and strategies. By 2015, the goal was to control the decline of biodiversity in key areas, through effective monitoring, strengthened in-situ conservation within existing protected areas, ex-situ conservation of small, wild species populations, and the creation of a system for supervision, evaluation, and resource trade management. By 2020, China is to control biodiversity loss altogether, through surveys, the establishment of a stable network of protected areas, and the improvement of the monitoring system. By 2030, biodiversity is to be effectively protected, with an adequate protected area coverage, a complete legal framework, and sustainable resource use. [45] To reach these goals, the Plan sets eight strategic tasks including policy changes, the mainstreaming of biodiversity in planning, in- and ex-situ conservation initiatives, sustainable resource use, and awareness-raising. [46]

The plan identifies 32 priority terrestrial areas of conservation, which are spread across the eight defined ecoregions of China. The Lower Hilly Region of South China region contains Guangdong province (of which Guangzhou is the capital). Only 2.9% of the ecoregion is presently protected. The plan sets conservation priorities, the first of which is to secure ecosystems including the lower subtropical monsoon evergreen broad leaved forest. Other emphases contain the protection of national key animal species, crops and wild plants, and the documentation of relevant traditional knowledge in minority-inhabited areas. [47]

National

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment is responsible for biodiversity conservation on a national level. In addition to the NBSAP, the Ministry has elaborated multiple “five year plans for eco-environmental protection,” the last of which was published in 2016. [48]

Regional

On a provincial level, the Guangdong Department of Environmental Protection is responsible for biodiversity conservation, elaborates ecological protection plans, conducts ecological assessments, supervises resource use, and coordinates the protection of flora and fauna in the province. [49]

The Guangdong province has its own 2013-2020 Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. The plan provides a catalog of all the ecosystems in the province, as well as a description of species diversity of fauna and flora. The document also provides an extensive description of current in- and ex-situ initiatives, citing namely the 7.4% of the province’s area that were protected by the end of 2012. [50]

The third chapter of the plan lists the objectives and actions that are to guide the province’s conservation efforts. The principles of the strategy include reducing unsustainable resource use, strengthening the government’s role in conservation, and promoting a participatory approach to conservation and raising awareness. Among its strategic goals, the province hopes to identify priority areas and actions, improve ecosystem and species conservation, to control alien invasive species, increase its protected area, improve in- and ex-situ conservation, improve research and monitoring, and to increase awareness and strengthen biodiversity education. [51]

Hong Kong also has a Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan for the years 2016-2016. [53]

Local

Locally, Guangzhou’s Bureau of Environmental Protection supervises natural resource exploitation, carries out environmental conservation and restoration initiatives, and enforces policies regarding clean production. [54] The Guangzhou Bureau of Forestry and Landscaping manages many natural reserves, leads greening and tree-planting initiatives, supervises the protection of plant and animal species [55]

Protected Areas Near City

The protected areas in the Pearl River Delta are quite small and fragmented. They include the Foshan Sanshui Dananshan Forest Park, the Dinghushan Scenic Area, the Shimen National Forest Park, the Maofeng Mountain and the Niuyuzui Primitive Ecological Scenic Area. Directly by Guangzhou, a reserve reserve complexe covers a decent area, and includes the SHanding Scenic Area, the Tianluhu Forest Park, the Dianjinfeng Scenic Area, the Huolushan Forest Park, the Luogang Ziangxue Park, the Maofenshan Forest Park, the Liantang Magnolia Forest park, and the Shanding Scenic Area. However, the complex is quite fragmented, and settlements have permeated the protected areas. Thus, in addition to its limited coverage, the protected area network in the delta does seem to be adequately managed.

Indeed, the designation of protected areas in China occurs without the input of locals, who often depend on natural resources from designated areas. As a result, locals rarely comply with resource use restrictions, which are hardly enforced due to lack of funds. Some studies even show that the designation of some protected areas worsens their fracturation, whether due to increased logging due to tourism, to ineffective management strategies, or because the ecosystems had actually benefited from some of the locals’ traditional practices. [56]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

NGO

The Nature Conservancy occupies an important role in conservation efforts in China, namely through its Conservation Blueprint program, which provided the background knowledge necessary for the elaboration of the NBSAP by the government. [57] The Wildlife Conservation Society also works in China to combat the trade of endangered species and to promote respect for wildlife. [58]

The World Wildlife Fund is very present in China, and elaborated a very detailed report on the state of biodiversity in the Pearl River Delta in 2007. The study identified multiple issues and possible solutions to challenges faced by ecosystems in the area. It underlines the lack of an adequate biodiversity knowledge management system, the increased flood risks in the delta, as well as the importance of Integrated River Basin Management. [59]

Although land cannot be privately owned in China, the government does distribute long-term leases that allows individuals to manage conservation areas. The Nature Conservancy is leading an initiative to support the creation of such Land Trust Reserves, in the hope of expanding the country’s protected area system. [60]

Public Awareness

Awareness of general environmental concerns seems quite high in China, especially concerning atmospheric pollution in large cities, and policymakers seem at least somewhat motivated to protect biodiversity. However the importance of ecosystem protection does not seem to be known to the general population, as illegal activities continue to threaten natural habitats..

[2] CEPF. “Indo-Burma.” Accessed August 5, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/indo-burma.

[3] CEPF. “Indo-Burma - Species.” Accessed August 5, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/indo-burma/species.

[4] “Pygmy Slow Loris.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 5, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[5] “Delacour’s Langur.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 5, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[6] CEPF. “Indo-Burma - Threats.” Accessed August 5, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/indo-burma/threats.

[7] Global Species, “South China-Vietnam subtropical evergreen forests,” https://www.globalspecies.org/ecoregions/display/IM0149 (accessed August 17, 2018).

Global Species, “Jian Nan subtropical evergreen forests,” https://www.globalspecies.org/ecoregions/display/IM0118 (accessed August 17, 2018).

[8] World Wildlife Fund, “Southeastern Asia: Southeastern China and northwest Vietnam,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0149 (accessed August 17, 2018).

[9] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Eastern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0118.

[10] WWF. “Eastern Asia: Eastern China | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0118.

[11] “Jian Nan Subtropical Evergreen Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 6, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/40118.

[12] Guangzhou.chn.info, “History of Guangzhou,” http://www.guangzhou.chn.info/overview/history-of-guangzhou.html (accessed August 17, 2018).

[13] Guangzhou.chn.info, “History of Guangzhou,” http://www.guangzhou.chn.info/overview/history-of-guangzhou.html (accessed August 17, 2018).

[14] Guangzhou.chn.info, “History of Guangzhou,” http://www.guangzhou.chn.info/overview/history-of-guangzhou.html (accessed August 17, 2018).

[15] Encyclopedia Britannica, “Guangzhou,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Guangzhou (accessed August 17, 2018).

[16] Didi Kirsten Tatlow, “China Air Quality Study Has Good News and Bad News,” New York Times (March 30, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/31/world/asia/china-air-pollution-beijing-shanghai-guangzhou.html.

Nishtha Chugh, “Three Reasons Why You Should Bet On Guangzhou As The Next Big Global City,” Forbes (June 15, 2017), https://www.forbes.com/sites/nishthachugh/2017/06/15/three-reasons-why-you-should-bet-on-guangzhou-as-next-big-global-city/#4fefa4e32dc9.

[17] Nishtha Chugh, “Three Reasons Why You Should Bet On Guangzhou As The Next Big Global City,” Forbes (June 15, 2017), https://www.forbes.com/sites/nishthachugh/2017/06/15/three-reasons-why-you-should-bet-on-guangzhou-as-next-big-global-city/#4fefa4e32dc9.

[18] Wang Haotong, “Guangzhou’s rubbish charge struggle” China Dialogue (July 23, 2017), https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/5057-Guangzhou-s-rubbish-charge-struggle.

[19] Yajie Dong & Yadong Mei, “Influence of Urbanization on the Surface Water Quality in Guangzhou, China” Wuhan University Journal of Natural Sciences 15, no. 1 (2010).

[20] Life of Guangzhou, “Guangzhou battles pollution to protect its rivers” (January 8, 2018) "http://www.lifeofguangzhou.com/article/content.do?contextId=7076&frontParentCatalogId=203.

[21] Li Rongde & Zhou Dongxhu, Caixin, “Raw Sewage Stinks Up Guangdong Waterways” (April 14, 2017), https://www.caixinglobal.com/2017-04-14/101078605.html.

[22] CEIC, “China Population, Guangdong, Guangzhou, Household Registration,” https://www.ceicdata.com/en/china/population-prefecture-level-city/population-guangdong-guangzhou-household-registration (accessed August 18, 2017).

Ed Fuller, “China's Crown Jewel: The Pearl River Delta,” Forbes (October 2, 2017), https://www.forbes.com/sites/edfuller/2017/10/02/chinas-crown-jewel-the-pearl-river-delta/#54174c8d5047.

[23] Alan Leung Sze-Iun et al., “Epson Pearl River Delta Scoping Study” (2007).

[24] Yanyan Wu, Shuyuan Li & Shixiao Yu, “Monitoring urban expansion and its effects on land use and land cover changes in Guangzhou city, China,” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 188, no. 1 (January 2016).

[25] Xuezhu Cui et al., “Driving factors of urban land growth in Guangzhou and its implications for sustainable development,” Frontier of Earth Sciences (2018).

[26] Zhigang Li & Fulong Wu, “Residential Satisfaction in China's Informal Settlements: A Case Study of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou,” Urban Geography 34, no. 7 (2013).

Ding Chengri & Yi Niu, “Urbanization and emerging land use patterns,” in Zheng Yongnian, Zhao Litao & Sarah Tong (eds) China’s Great Urbanization ( ??? Taylor & Francis, 2016), 155.

[27] Zhigang Li & Fulong Wu, “Residential Satisfaction in China's Informal Settlements: A Case Study of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou,” Urban Geography 34, no. 7 (2013).

[28] Yanyan Wu, Shuyuan Li & Shixiao Yu, “Monitoring urban expansion and its effects on land use and land cover changes in Guangzhou city, China,” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 188, no. 1 (January 2016).

[29] Li Yu, Chinese City and Regional Planning Systems , (Farnham, Surry: Ashgate, 2014), ??.

[30] Sascha Matuszak, “What’s Behind China’s Green Space Crackdown,” Next City (March 20, 2015), https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/china-greenspace-crackdown-rapid-urbanization.

[31] Encyclopedia Britannica, “Guangzhou,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Guangzhou (accessed August 17, 2018).

[32] Alan Leung Sze-Iun et al., “Epson Pearl River Delta Scoping Study” (2007).

[33] Xuezhu Cui et al., “Driving factors of urban land growth in Guangzhou and its implications for sustainable development,” Frontier of Earth Sciences (2018).

[34] “China to unveil Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao development plan soon: official,” Xinhua (May 16, 2018), http://english.gov.cn/state_council/ministries/2018/05/16/content_281476149575028.htm.

[35] Guangdong Provincial Development and Reform Commission, “Home,” http://www.gddrc.gov.cn/ (accessed August 17, 2018).

[36] Guangdong Provincial Development and Reform Commission, “Pearl River Delta Urban and Rural Planning Integration Plan (2009-2020),” http://www.gddrc.gov.cn/ztzl/lszt/zsjfzghgy/zcwj/201410/t20141023_427960.shtml (accessed August 17, 2018).

[37] Guangdong Development and Reform Commission, “Pearl River Delta Urban and Rural Planning Integration Plan (2009-2020)” (2009), http://www.gddrc.gov.cn/gov/gkml/201506/t20150630_320687.html.

[38] Guangzhou Municipal People’s Government, “Notice of the Guangzhou Municipal People’s Government on Printing and Distributing the Outline of the 13th five-year plan for National Economic and Social Development of Guangzhou, 2016-2020,” (2016).

[39] Liu Zhen, “Beijing approves Guangzhou’s blueprint for 2020,” South China Morning Post (February 21, 2016), , https://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/1915122/beijing-approves-guangzhous-blueprint-2020.

[40] Guangzhou Land Resources and Planning Commission, “Draft of Guangzhou City master Plan, 2017-2035” (2017).

[41] Guangzhou Land Resources and Planning Commission, “Draft of Guangzhou City master Plan, 2017-2035” (2017)

[42] Guangzhou Land Resources and Planning Commission, “Draft of Guangzhou City master Plan, 2017-2035” (2017).

[43] Guangzhou Land Resources and Planning Commission, “Draft of Guangzhou City master Plan, 2017-2035” (2017).

[44] Guangzhou Land Resources and Planning Commission, “Draft of Guangzhou City master Plan, 2017-2035” (2017).

[45] Ministry of Environmental Protection, “China National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan, 2011-2030” 2011

[46] Ministry of Environmental Protection, “China National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan, 2011-2030” 2011

[47] Ministry of Environmental Protection, “China National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan, 2011-2030” 2011, 20

[48] People’s Republic of China, Ministry of Ecology and Environment, “Plans,” http://english.mep.gov.cn/Resources/Plans/, (accessed August 17, 2018).

[49] Guangdong Department of Environemntal Protection, “Duties of the Department of Environmental Protection of Guangdong Province,” http://www.gdep.gov.cn/eng/GDEP/201303/t20130322_151717.html, (accessed August 17, 2018).

[50] Guangdong Provincial Department of Environmental Protection, “Guangdong Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, 2013-2020” (November 2013).

[51] Guangdong Provincial Department of Environmental Protection, “Guangdong Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, 2013-2020” (November 2013).

[52] Guangdong Provincial Department of Environmental Protection, “Guangdong Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, 2013-2020” (November 2013), 25.

[53] HK BIodiversity, “Hong Kong Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, 2016-2021” (December 2016).

[54] Guangzhou International, “Bureau of Environmental Protection of Guangzhou Municipality,” http://english.gz.gov.cn/gzgoven/s3709/201008/787544.shtml (accessed August 17, 2018).

[55] Guangzhou International, “Bureau of Forestry and Landscaping of Guangzhou Municipality,” http://english.gz.gov.cn/gzgoven/s3709/201008/787562.shtml (accessed August 17, 2018).

[56] Emily Yeh, “Do China’s nature reserves only exist on paper?,” China Dialogue (February 3, 2014) https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/6696-Do-China-s-nature-reserves-only-exist-on-paper-.

[57] Zhang Shuang, “Building a Green China,” Talk (October 7, 2010), https://blog.nature.org/conservancy/2010/10/07/building-a-green-china/.

[58] WCS China, “WCS China,” https://china.wcs.org/ (accessed August 17, 2018).

[59] Alan Leung Sze-Iun et al., “Epson Pearl River Delta Scoping Study” (2007).

[60] Charles Bedfore & Jin Tong, National Geographic, “Transforming Conservation in China with ‘Land Trust Reserves’” (August 24, 2016), https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2016/08/24/transforming-conservation-in-china-with-land-trust-reserves/.