Guayaquil, Ecuador

- Global Location plan: 2.17oS, 79.92oW

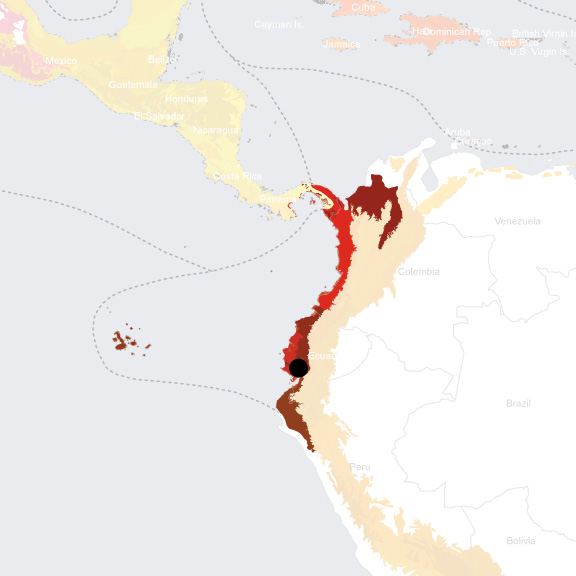

- Hotspot: Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena

- Population 2015: 2,709,000

- Projected population 2030: 3,493,000

- Mascot Species: ceiba (Ceiba trichistandra)[1],

- Primary Crops: cacao, coffee, sugarcane, bananas, citrus fruits, mangoes, palm oil, and rice.[2]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Atelopus nanay

- Niceforonia nigrovittata

- Atelopus guanujo

- Telmatobius vellardi

- Hyalinobatrachium valerioi

- Pristimantis croceoinguinis

- Hyloscirtus phyllognathus

- Rhinella marina

- Pristimantis pyrrhomerus

- Hyloxalus anthracinus

- Atelopus halihelos

- Pristimantis atratus

- Epicrionops bicolor

- Engystomops puyango

- Pristimantis unistrigatus

- Pristimantis vidua

- Atelopus balios

- Atelopus balios

- Atelopus exiguus

- Atelopus spumarius

- Excidobates captivus

- Gastrotheca cornuta

- Gastrotheca plumbea

- Gastrotheca riobambae

- Hyloscirtus lindae

- Boana pellucens

- Boana rosenbergi

- Smilisca phaeota

- Trachycephalus jordani

- Pristimantis baryecuus

- Pristimantis bromeliaceus

- Pristimantis cajamarcensis

- Pristimantis curtipes

- Pristimantis exoristus

- Pristimantis muscosus

- Pristimantis nephophilus

- Pristimantis nigrogriseus

- Pristimantis ockendeni

- Pristimantis orestes

- Pristimantis pecki

- Pristimantis percnopterus

- Pristimantis pycnodermis

- Pristimantis riveti

- Pristimantis rufioculis

- Pristimantis serendipitus

- Pristimantis spinosus

- Pristimantis w-nigrum

- Leptodactylus labrosus

- Noblella lochites

- Engystomops petersi

- Telmatobius cirrhacelis

- Lithobates bwana

- Siphonops annulatus

- Engystomops guayaco

- Espadarana durrellorum

- Hyloxalus parcus

- Atelopus petersi

- Lynchius flavomaculatus

- Hyloxalus nexipus

- Pristimantis katoptroides

- Pristimantis rhodostichus

- Pristimantis incomptus

- Lithobates catesbeianus

- Gastrotheca lojana

- Pristimantis acuminatus

- Pristimantis enigmaticus

- Leptodactylus wagneri

- Telmatobius niger

- Rhinella festae

- Espadarana prosoblepon

- Chimerella mariaelenae

- Rulyrana mcdiarmidi

- Atelopus nepiozomus

- Atelopus palmatus

- Gastrotheca pseustes

- Trachycephalus typhonius

- Ceratophrys stolzmanni

- Pristimantis cryophilius

- Gastrotheca monticola

- Pristimantis lymani

- Pristimantis quaquaversus

- Leptodactylus melanonotus

- Pristimantis versicolor

- Atelopus arthuri

- Hyloxalus exasperatus

- Pristimantis truebae

- Atelopus boulengeri

- Rhinella amabilis

- Rhaebo caeruleostictus

- Centrolene buckleyi

- Nymphargus cariticommatus

- Nymphargus cochranae

- Nymphargus posadae

- Cochranella resplendens

- Hyloxalus fallax

- Hyloxalus infraguttatus

- Allobates insperatus

- Colostethus jacobuspetersi

- Hyloxalus peculiaris

- Hyloxalus pumilus

- Hyloxalus shuar

- Hyloxalus vertebralis

- Epipedobates anthonyi

- Epipedobates tricolor

- Gastrotheca litonedis

- Gastrotheca psychrophila

- Hyloscirtus alytolylax

- Hyloscirtus pacha

- Scinax quinquefasciatus

- Pristimantis achatinus

- Pristimantis balionotus

- Pristimantis ceuthospilus

- Pristimantis chalceus

- Pristimantis colodactylus

- Pristimantis condor

- Strabomantis cornutus

- Pristimantis cryptomelas

- Diasporus gularis

- Craugastor longirostris

- Pristimantis modipeplus

- Pristimantis pastazensis

- Pristimantis percultus

- Pristimantis petersi

- Pristimantis philipi

- Pristimantis phoxocephalus

- Pristimantis ruidus

- Pristimantis simonbolivari

- Pristimantis subsigillatus

- Pristimantis trachyblepharis

- Pristimantis walkeri

- Lynchius simmonsi

- Lithodytes lineatus

- Engystomops montubio

- Engystomops randi

- Atelopus ignescens

- Ctenophryne aequatorialis

- Pristimantis parvillus

- Atelopus podocarpus

- Pristimantis bambu

- Engystomops pustulatus

- Caecilia abitaguae

- Caecilia disossea

- Caecilia tenuissima

- Barycholos pulcher

- Hyloscirtus psarolaimus

- Nymphargus buenaventura

- Leptodactylus peritoaktites

- Atelopus onorei

- Pristimantis orcesi

- Engystomops pustulatus

- Espadarana audax

- Callimedusa ecuatoriana

- Gastrotheca weinlandii

- Epipedobates machalilla

- Gastrotheca lateonota

- Pristimantis galdi

- Hyloxalus elachyhistus

- Pristimantis proserpens

- Excidobates condor

- Atelopus bomolochos

- Pristimantis metabates

- Leptodactylus ventrimaculatus

- Noblella heyeri

- Atelopus bomolochos

- Atelopus bomolochos

- Caecilia pachynema

Mammals

- Phylloderma stenops

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Mesomys hispidus

- Mesoplodon ginkgodens

- Microryzomys altissimus

- Microryzomys minutus

- Microsciurus flaviventer

- Leopardus colocolo

- Tadarida brasiliensis

- Molossops aequatorianus

- Neusticomys monticolus

- Pteronotus gymnonotus

- Nyctinomops laticaudatus

- Oligoryzomys destructor

- Nephelomys albigularis

- Transandinomys talamancae

- Panthera onca

- Proechimys simonsi

- Vampyressa thyone

- Sciurus granatensis

- Phyllotis andium

- Phyllotis gerbillus

- Phyllotis haggardi

- Platyrrhinus infuscus

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Transandinomys bolivaris

- Oecomys bicolor

- Melanomys caliginosus

- Pattonomys occasius

- Saguinus fuscicollis

- Marmosops noctivagus

- Marmosa regina

- Philander andersoni

- Odocoileus virginianus

- Platyrrhinus lineatus

- Phyllostomus discolor

- Lasiurus cinereus

- Ateles fusciceps

- Panthera onca

- Zalophus wollebaeki

- Rhogeessa io

- Rhogeessa velilla

- Vampyrodes caraccioli

- Sturnira koopmanhilli

- Sturnira ludovici

- Platyrrhinus helleri

- Platyrrhinus dorsalis

- Platyrrhinus nitelinea

- Thyroptera tricolor

- Platyrrhinus ismaeli

- Myoprocta pratti

- Tayassu pecari

- Centronycteris centralis

- Puma concolor

- Nyctinomops macrotis

- Eumops wilsoni

- Promops centralis

- Thomasomys caudivarius

- Marmosa phaea

- Anoura fistulata

- Heteromys teleus

- Thomasomys erro

- Platyrrhinus nigellus

- Sturnira oporaphilum

- Caenolestes condorensis

- Thomasomys hudsoni

- Myotis keaysi

- Rhynchonycteris naso

- Lasiurus ega

- Melanomys robustulus

- Alouatta juara

- Artibeus aequatorialis

- Peponocephala electra

- Tursiops truncatus

- Choloepus hoffmanni

- Pudu mephistophiles

- Lophostoma silvicolum

- Aegialomys xanthaeolus

- Ichthyomys hydrobates

- Macrophyllum macrophyllum

- Nephelomys auriventer

- Potos flavus

- Sturnira magna

- Oreoryzomys balneator

- Eptesicus innoxius

- Stenella longirostris

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Tanyuromys aphrastus

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Pecari tajacu

- Nasua narica

- Vicugna vicugna

- Mus musculus

- Vampyriscus bidens

- Cryptotis equatoris

- Saccopteryx bilineata

- Grampus griseus

- Mormoops megalophylla

- Eptesicus chiriquinus

- Micronycteris hirsuta

- Thomasomys fumeus

- Chilomys instans

- Diclidurus albus

- Eptesicus innoxius

- Cerdocyon thous

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Histiotus montanus

- Sciurus igniventris

- Caenolestes fuliginosus

- Rhinophylla pumilio

- Saccopteryx leptura

- Sturnira tildae

- Glironia venusta

- Gardnerycteris crenulatum

- Chiroderma villosum

- Ichthyomys stolzmanni

- Platyrrhinus fusciventris

- Orcinus orca

- Bradypus variegatus

- Dasypus novemcinctus

- Herpailurus yagouaroundi

- Hylaeamys tatei

- Thomasomys baeops

- Proechimys decumanus

- Thomasomys paramorum

- Thomasomys pyrrhonotus

- Glossophaga commissarisi

- Puma concolor

- Pithecia napensis

- Lycalopex sechurae

- Monodelphis adusta

- Caenolestes sangay

- Sciurus spadiceus

- Sturnira bakeri

- Myotis oxyotus

- Sturnira nana

- Saimiri sciureus

- Aotus vociferans

- Plecturocebus discolor

- Eira barbara

- Delphinus delphis

- Thomasomys cinnameus

- Sigmodon inopinatus

- Thomasomys silvestris

- Tremarctos ornatus

- Dinomys branickii

- Carollia castanea

- Priodontes maximus

- Platyrrhinus matapalensis

- Thomasomys aureus

- Philander opossum

- Lagenodelphis hosei

- Noctilio leporinus

- Cebus albifrons

- Cyclopes didactylus

- Micronycteris minuta

- Caluromys lanatus

- Caenolestes caniventer

- Thomasomys taczanowskii

- Anoura geoffroyi

- Makalata macrura

- Bassaricyon alleni

- Ichthyomys tweedii

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Rhinophylla alethina

- Rhipidomys latimanus

- Coendou rufescens

- Rhipidomys leucodactylus

- Trinycteris nicefori

- Molossus rufus

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon hotaula

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Myotis nigricans

- Lagidium ahuacaense

- Choeroniscus minor

- Saccopteryx canescens

- Sigmodontomys alfari

- Sturnira bidens

- Sturnira bogotensis

- Sturnira erythromos

- Sturnira luisi

- Lagothrix poeppigii

- Marmosa rubra

- Metachirus nudicaudatus

- Indopacetus pacificus

- Cryptotis montivaga

- Molossus bondae

- Didelphis pernigra

- Chibchanomys orcesi

- Coendou quichua

- Lonchophylla concava

- Vampyrum spectrum

- Anoura caudifer

- Anoura aequatoris

- Anoura peruana

- Lophostoma occidentalis

- Lasiurus blossevillii

- Promops davisoni

- Bassaricyon medius

- Bassaricyon medius

- Promops nasutus

- Speothos venaticus

- Stenella attenuata

- Hylaeamys yunganus

- Nyctinomops aurispinosus

- Alouatta palliata

- Tamandua mexicana

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Eptesicus furinalis

- Lycalopex culpaeus

- Kogia sima

- Cynomops abrasus

- Sigmodon peruanus

- Carollia brevicauda

- Carollia perspicillata

- Amorphochilus schnablii

- Mazama americana

- Cuniculus paca

- Anoura cultrata

- Artibeus fraterculus

- Enchisthenes hartii

- Artibeus lituratus

- Didelphis marsupialis

- Marmosops impavidus

- Marmosops caucae

- Chironectes minimus

- Dasyprocta punctata

- Thomasomys auricularis

- Oligoryzomys fulvescens

- Sciurus stramineus

- Eumops auripendulus

- Desmodus rotundus

- Conepatus semistriatus

- Eptesicus andinus

- Eptesicus brasiliensis

- Feresa attenuata

- Marmosa murina

- Nasuella olivacea

- Leopardus pardalis

- Lonchorhina aurita

- Lontra longicaudis

- Mesophylla macconnelli

- Platalina genovensium

- Lichonycteris obscura

- Proechimys semispinosus

- Micronycteris megalotis

- Molossus molossus

- Myotis albescens

- Neacomys spinosus

- Trachops cirrhosus

- Dermanura phaeotis

- Handleyomys alfaroi

- Euryoryzomys macconnelli

- Peropteryx kappleri

- Phyllostomus hastatus

- Cuniculus taczanowskii

- Akodon aerosus

- Neomicroxus latebricola

- Akodon mollis

- Amorphochilus schnablii

- Necromys punctulatus

- Aotus lemurinus

- Coendou bicolor

- Ateles belzebuth

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Caluromys derbianus

- Peropteryx macrotis

- Kogia breviceps

- Mesoplodon peruvianus

- Proechimys cuvieri

- Uroderma bilobatum

- Dermanura rava

- Diphylla ecaudata

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Chiroderma salvini

- Glossophaga soricina

- Cavia patzelti

- Tapirus pinchaque

- Tapirus terrestris

- Mazama rufina

- Myotis riparius

- Reithrodontomys mexicanus

- Leopardus wiedii

- Lonchophylla handleyi

- Lonchophylla hesperia

- Lonchophylla robusta

- Lonchophylla thomasi

- Mustela frenata

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena extends south and east from the Panama Canal, through western Colombia, Ecuador, and into northwestern Peru. It also encompasses the Galápagos Islands. The hotspot sustains a wide variety of habitats, ranging from mangroves, beaches, rocky shorelines, to some of the world’s wettest rainforests. “Islands” of high endemism are scattered throughout the relatively flat coastal plains as a few small mountain systems. [3]

Species statistics [4]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage of endemics |

Notable species |

|

Plants |

11,000 |

25% |

- ceiba ( Ceiba trichistandra ) |

|

Birds |

~900 |

~12% |

|

|

Mammals |

DD |

DD |

|

|

Reptiles |

>320 |

~30% |

- marine iguana ( Amblyrhynchus cristatus ) |

|

Amphibians |

>200 |

~15% |

- poison dart frogs ( Dendrobatidae ) |

|

Freshwater Fishes |

~250 |

~50% |

|

The northern parts of the hotspot are characterized by extremely wet or pluvial forests of eight meters of rainfall per annum. Within which, Colombian Chocó province is the most floristically diverse area in the Neotropics. The dry forests in the south are in turn dominated by large, emergent trees, including the giant ceiba ( Ceiba trichistandra ). The Galápagos Islands also boost incredibly high plant diversity (nearly 700 species), of which about a quarter are endemic. [5] Amongst the hotspot’s distinctive birds are the Endangered white-winged guan [6] ( Penelope albipennis ) and the Vulnerable long-wattled umbrella bird [7] ( Cephalopterus penduliger ), of which the ranges overlap or are very near the city of Guayaquil. Primates are the best-known mammals of the hotspot, including spider monkeys and bare-faced tamarins. The marine iguanas ( Amblyrhynchus cristatus ) are the most iconic reptiles. While new amphibian species continue to be rapidly discovered, the poison dart frogs ( Dendrobatidae ) are by far the most prominent. Many species are limited to habitats of only a few square kilometers, rendering them particularly vulnerable to any disturbance. Freshwater fish endemism is centered around the Magdalena and Atrata valleys. [8]

Deforestation is the principal threat in the Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena Biodiversity Hotspot. Poverty, land scarcity, and population growth fuel disorderly settlements and agricultural expansions. In the Baudó River region, around 80 percent of forests are converted. Oftentimes, national parks are also invaded. Intensive farming of banana, plantain, cocoa, coffee, and African palm prevails, especially in coastal Ecuador. In areas around Guayaquil, cattle ranching contributes to large-scale destruction of forests and wetlands. Unsustainable and illegal timber extractions are also a serious problem. [9]

CEPF invested US$6.95 million in the hotspot from 2002 to 2013. The funds supported innovative conservation tools such as payments for environmental services and incentive agreement schemes, and improved management by engaging indigenous and afro-descendant groups, providing alternative livelihood options. [10]

Guayaquil Flooded Grasslands

The Guayaquil Flooded Grasslands ecoregion is in the delta of the Guayas River of southwestern Ecuador, extending south to the mangroves of the Gulf of Guayaquil. The climate is equatorial with a distinct dry winter. Monthly precipitation ranges from less than 10 mm from July to November, to 265 mm in March. Temperatures are fairly consistent throughout the year, with a mean of 26°C (79 °F). Grasslands in the ecoregion are seasonally flooded and hold riparian flora. One notable species is the Endangered[i] Peruvian tern ( Sternula lorata ), of which the coastal habitat cover urban centers such as Guayaquil and Lima. Threats to biodiversity in the region stem from growth of human population and large-scale irrigation programs for agriculture. [11] Large areas have been converted to farmland or for extract usage. Presently, only 2 percent of the ecoregion is under protection, which is 2.2 percent terrestrially connected. [12]

Western Ecuador Moist Forests

The Western Ecuador Moist Forests ecoregion is located in southwestern Colombia and western Ecuador, concentrated in the province of Esmeraldas and Quinindé. It extends over coastal plains varying in width from 100 to 200 km, and of formations of volcanic-sedimentary rocks, resulting in fertile soils. The climate is characterized by the high influx of precipitation and the lack of a dry season. The northern, wetter half of the ecoregion averages more than 7,000 mm of rainfall per annum, while the dryer south still averages about 2,000 mm. The vegetation is dominated by a dense canopy of trees over 30 meters tall, rich in lianas and epiphytes, many of which are endemic. Mosses, lichens, ferns, and palms are also common. A huge number of endemic species in the ecoregion are restricted to narrow strips and on isolated mountain ridges. The level of endemism is particularly high for avifauna. The main threats to ecosystems are banana plantations and extraction of palm oil and rubber. Accelerated highway construction and oil exploration (especially between 1960 and 1980) facilitated further settlement in the region, leading to more felling of the forest and land conversion to pasture. [13] Currently, 5 percent of the ecoregion is conserved within half a dozen protected areas, with a 3.54 percent terrestrial connectivity. [14]

Environmental History

Before the arrival of Spaniards, the area surrounding Guayaquil was inhabited by indigenous groups . The Huancavilcas and the Chonos were dominant at the time of the arrival of the Spanish conquerers. [15] Guayaquil’s exact founding date is unknown because the European settlement had many locations before the Guayas River location became permanent. [16] During the Spanish occupation, Guayaquil grew as one of the main ports in the region and faced frequent buccaneer attacks. [17] The city grew around cacao production in the eighteenth century. [18] Guayaquil declared independence in 1820 and Ecuador, as part of Gran Colombia, became independent in 1822.

Since Ecuador's national independence in 1830, Guayaquil has been the country's first port and trading hub. The city's urban configuration formed around the production of cacao in the eighteenth century. A large fire in 1896 burned much of Guayaquil, requiring immense reconstruction. [19] Today, the city is a rich agricultural region with prawn farming on the mangroves. [20] Natural gas deposits were found in the Gulf of Guayaquil in 1970, and extraction and exploration of both oil and gas continues. [21] Since Guayaquil’s founding, ports have historically been built and replaced. The most recent plan is to move the port downstream, where undeveloped land is available. and dredge the access canal.

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

The Guayaquil flooded grasslands is most threatened by human population increase and irrigation practices. [22] Similarly, the Western Ecuador Moist Forest is most threatened by unsustainable agriculture and land conversion to settlement and pasture. Banana plantations, palm oil extraction, and shrimp farming majorly threatened the moist forest, while large scale irrigation projects and cattle ranching alter the flooded grasslands. [23] In addition to land conversion, unsustainable agriculture often attracts foreign capital, which then forces poor and indigenous populations to occupy protected lands. [24] Construction of highways is also a factor, both directly from land clearing and indirectly from the resulting urbanization and agricultural expansion. [25] Oil and gas exploration has also degraded habitats and displaced indigenous communities. [26]

In Ecuador, only about 2% of the native coastal forest remains. It’s one of the most threatened tropical forest systems globally. [27]

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Like other cities in developing countries, Guayaquil’s urban landscape includes informal settlements. Around 600,000 Guayaquil residents live in informal settlements, which are a result of insufficient city planning and infrastructure to deal with the city’s accelerated growth. [28] The formal development of Guayaquil is geared towards tourism instead of improving public welfare; informal activity is cleansed more often than incorporated. [29] Growth in region also takes place in nearby cities like Duran and Samborondon

Governance

Ecuador is a representative democratic republic with a unicameral legislature, constitution, and president. There are five branches of the government: Executive, Legislative, Judicial, Electoral, and Transparency and Social Control. Administratively, Ecuador is divided into provinces, which are then divided into cantons. Guayaquil is the capital of the province Guayas. Ecuador has 9 zones, which join 2 or more provinces into one region to decentralize administrative power from the Ecuadorian capital Quito. [30] Guayaquil doesn’t share these powers with another province, but instead shares them with Duran and Samborondon separate from the rest of Guayas. Ecuador has departments for the Environment and Planning & Development.

City Policy/Planning

Development Plan

I cannot find evidence of a comprehensive urban development plan after 1976. [31]

The “urban regeneration” of Guayaquil is not a master plan but rather a series of projects sponsored by the local government. The Malecon 2000 and Guayaquil Siglo 21 urban schemes focus on interventions that improve the physical and visual environment. El Malecon del Salado is the main project of this urban regeneration. El Malecon del Salado is a boardwalk that goes through both formal and informal areas along the waterfront. [32] Along the formal section of the boardwalk, there are structures that have food, clubs, and walkways. Along the informal section of the boardwalk, in which the boardwalk is separated from the edge of the land, there are entry points with food kiosks to 15 feet wide public spaces. Another project is the Las Penas and Cerro Santa Ana beautification project. [33] The Las Penas neighborhood had been neglected and adopted informal characteristics. To revitalize the area, houses near the boardwalk were painted bright colors. A large mixed use development called Puerto Santa Ana has been built and a residential and business development called La Ciudad en el Rio is planned for the area; these developments, in addition to the formalization of the land, will most likely displace current residents.

Another project is Guayaquil Masterplan designed by perkins eastman. [34] The City of Guayaquil plans to move the Jos de Olmedo Airport to outside the city limits by 2024. The plan and concept, called “La Nueva Ciudad,” aims to create a center of sustainable urbanism that connects different areas and people of Guayaquil. The plan has three districts: garden, marina, and central. It includes a Green Highway System to connect animals and pedestrians to the natural surroundings, increasing public transportation, and infrastructure for waste and water. [35]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Ecuador’s current National Biodiversity Strategy, which covers 2015 to 2030, incorporates new national provisions to the previous NBSAP. [38] Under the new constitution (adopted in 2008), Ecuador has become the first country to recognize nature as a rights-bearing entity. The NBS also declares the protection of nature as a national strategy and has an entire chapter dedicated to biodiversity and natural resources. [39] Ecuador's Plan contains four objectives: mainstreaming in public policy management; reduction of pressures and misuse of biodiversity; equitable benefit-sharing, taking into account specific details related to gender and interculturality; and the strengthening of knowledge management and capacities that promote innovation in biodiversity matters. Management and measurement of the implementation is also proposed.

National

Ecuador’s National Development Plan 2013-2017, also known as the National Plan for Good Living, is a document by the National Secretariat of Planning and Development that covers national strategy under Good Living. [40] Good Living is a development model that aims not for capitalist growth but for happiness and permanence of cultural and environmental diversity. A society in harmony with Nature is a stated principle of the development plan. Particularly, Objective 7 is to "guarantee the rights of nature and promote territorial and global environmental sustainability." Ecuador plans to recover all species in danger of extinction, ensure biodiversity conservation, create a national inventory of plants and animals, consolidate forest management, and reduce human threats to ecosystems.

Protected Areas

Ecuador has the National System of Protected Areas (SNAP), which is a group of protected natural areas that ensure ecosystem health. [41] It’s 56 reserves cover about twenty percent of Ecuador’s total area. The general objectives are to ensure biodiversity health, encourage sustainable resource use, and involve local communities. SNAP has four subsystems: State, Autonomous and decentralized, Community based, and Privately owned.

The Bosque Protector Cerro Blanco is a tropical dry forest nature preserve directly west of central Guayaquil, privately owned by Holcim Ecuador. 54 species of mammals and 220 birds can be found in the preserve; it is known for jaguars and howler monkeys. [42]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The Biodiversity Group has an initiative called the Ecuadorian Biodiversity Project. Noting Ecuador as one of the most biodiverse nations in the world, the project aims to conserve Ecuador’s threatened biodiversity through documentation, study, and outlining conservation recommendations. [43] So far, the project has discovered 30 species previously unknown.

The TEEB Ecuador Project focuses on studying the effect of different programmes of the economy, landscape, and biodiversity of different watersheds. In the Guayas watershed, the project focuses on on mainstreaming biodiversity conservation and sustainable use into agricultural landscapes, with a particular focus on smallholder farming. [44] Scenarios that focus on different sectors, such as hydrocarbon, and infrastructure projects, such as flood control and irrigation, are analyzed to see what programs would produce the most agricultural productivity with the least damage to biodiversity

Public Awareness

Public awareness seems high. The constitution, which established nature as a rights-bearing entity, was voted in by referendum. Yet despite clear popular support for biodiversity initiatives, the degree to which the public has power in guiding government strategy and private projects is unclear. The frequently expressed collusion between the government and private sector, in addition to the high level of poverty, imply that the population is often shut out from influencing large scale policy and projects.

[1] CEPF. “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena - Species.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena/species.

[2] Country Studies, “Crops,” http://countrystudies.us/ecuador/46.htm (accessed August 16, 2018)

[3] CEPF. “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena.

[4] CEPF. “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena - Species.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena/species.

[5] CEPF. “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena - Species.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena/species.

[6] “White-Winged Guan.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[7] “Long-Wattled Umbrellabird.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[8] CEPF. “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena - Species.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena/species.

[9] CEPF. “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena - Threats.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena/threats.

[10] CEPF. “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena.

[11] “Guayaquil Flooded Grasslands.” In Wikipedia, April 19, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Guayaquil_flooded_grasslands&oldid=776180422.

[12] “Guayaquil Flooded Grasslands.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60905.

[13] WWF. “Northern South America: Northwestern Ecuador and Southwestern Colombia | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0178.

[14] “Western Ecuador Moist Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60178.

[15] Metropolitan Touring, “The Founding of Guayaquil,” https://www.metropolitan-touring.com/founding-of-guayaquil/ (accessed August 31, 2018)

[16] ibid.

[17] Lonely Planet, “History,” https://www.lonelyplanet.com/ecuador/pacific-coast-and-lowlands/guayaquil/history (accessed August 31, 2018)

[18] Architecture in Development, “UPGRADING INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS - A CASE STUDY FROM ECUADOR,” http://www.architectureindevelopment.org/news.php?id=39 (accessed August 31, 2018)

[19] Lonely Planet, “History,” https://www.lonelyplanet.com/ecuador/pacific-coast-and-lowlands/guayaquil/history (accessed August 31, 2018)

[20] AiVP, “Guayaquil (Ecuador): the spectacular urban metamorphosis of a port-metropolis,” http://www.aivp.org/members/files/2013/10/Guayaquil201310_EN.pdf (accessed August 30, 2018)

[21] Oil & Gas Journal, “Ecuador goes offshore with new participation contract offerings,” https://www.ogj.com/articles/2002/11/ecuador-goes-offshore-with-new-participation-contract-offerings.html (accessed August 31, 2018)

[22] WWF, “Western South America: Western Ecuador,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0905 (accessed August 24, 2018)

[23] CEPF, “TUMBES-CHOCÓ-MAGDALENA - THREATS,” https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena/threats (accessed August 24, 2018)

[24] ibid.

[25] Revolvy, “Western Ecuador Moist Forests,” https://www.revolvy.com/page/Western-Ecuador-moist-forests (accessed August 24, 2018)

[26] WWF, “Northern South America: Northwestern Ecuador and southwestern Colombia,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0178 (accessed August 24, 2018)

[27] Revolvy, “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena,” https://www.revolvy.com/page/Tumbes%252DChoc%C3%B3%252DMagdalena (accessed August 24, 2018)

[28] Architecture in Development, “UPGRADING INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS - A CASE STUDY FROM ECUADOR,” http://www.architectureindevelopment.org/news.php?id=39 (accessed August 24, 2018)

[29] Xavier Andrade, “‘More City,’ Less Citizenship: Urban Renovation and the Annihilation of Public Space”, in Fernando Carrion M. and Lisa M. Harley (eds) Urban Regeneration and Revitalization in the Americas: Toward a Stable State (Washington DC: Wilson Center, 2004)

[30] Planning and Development, “Administrative planning levels,” http://www.planificacion.gob.ec/3-niveles-administrativos-de-planificacion/ (accessed August 24, 2018)

[31] United Nations Archive

[32] FAVELissies, “PROJECT 1: Malecon del Salado,” https://favelissues.com/2010/01/20/project-1-malecon-del-salado/ (accessed August 27, 2018)

[33] FAVELissues, “PROJECT 2: Las Peñas + Cerro Santa Ana,” https://favelissues.com/2010/01/22/project-2-las-penas-cerro-santa-ana/ (accessed August 27, 2018)

[34] Wan Urban Challenge, “Guayaquil Masterplan, Guayaquil, Ecuador Perkins Eastman,” http://www.wanurbanchallenge.com/project/guayaquil-masterplan/?source=architect (accessed August 27, 2018)

[35] Perkins Eastment, “The New City, Guayaquil,” www.perkinseastman.com/dynamic/document/week/news/download/3440489/3440489.pdf (accessed August 27, 2018)

[36] Wan Urban Challenge, “Guayaquil Masterplan, Guayaquil, Ecuador Perkins Eastman,” http://www.wanurbanchallenge.com/project/guayaquil-masterplan/?source=architect (accessed August 27, 2018)

[37] Perkins Eastment, “The New City, Guayaquil,” www.perkinseastman.com/dynamic/document/week/news/download/3440489/3440489.pdf (accessed August 27, 2018)

[38] CBD, “Latest NBSAPs,” https://www.cbd.int/nbsap/about/latest/default.shtml (accessed August 31, 2018)

[39] The Constitute Project, “Ecuador's Constitution of 2008,” https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Ecuador_2008.pdf (accessed August 31, 2018)

[40] Planning and Development, “Good Living National Plan 2013-2017,”

[41] National System of Protected Areas, “NATIONAL SYSTEM OF PROTECTED AREAS - NSPA,” http://areasprotegidas.ambiente.gob.ec/en/info-snap (accessed September 17, 2018)

[42] Ecuavisa, “Recorre la naturaleza en el bosque protector Cerro Blanco,” http://www.ecuavisa.com/articulo/guayaquil-mi-destino/215036-recorre-naturaleza-bosque-protector-cerro-blanco (accessed September 17, 2018)

[43] The Biodiversity Project, “Project Home,” https://biodiversitygroup.org/ecuador/ (accessed September 14, 2018)

[44] The Economics and Ecosystems of Biodiversity, “Ecuador,” http://teebweb.org/training/areas-of-work/teeb-country-studies/ecuador-2/ (accessed September 14, 2018)