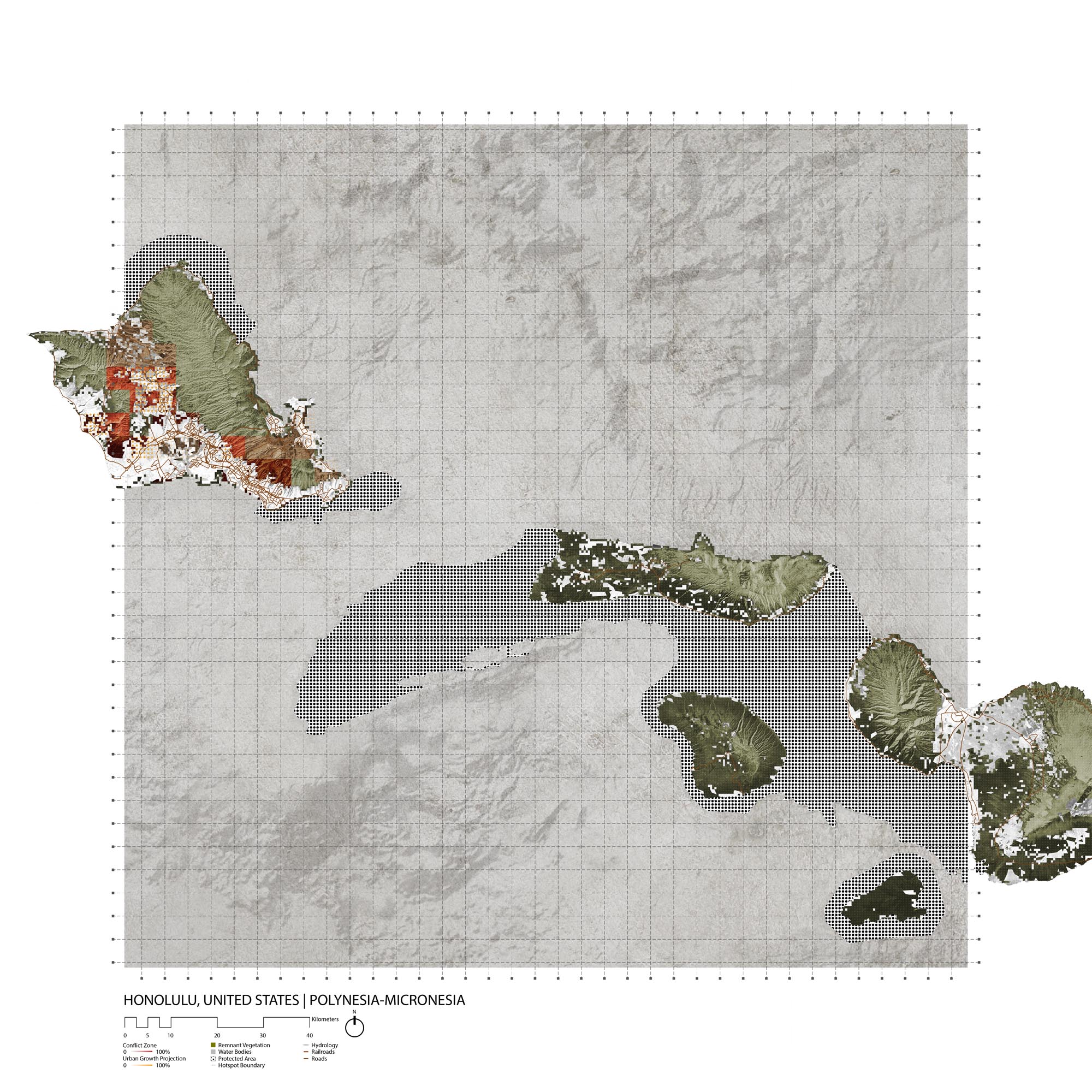

Honolulu, United States

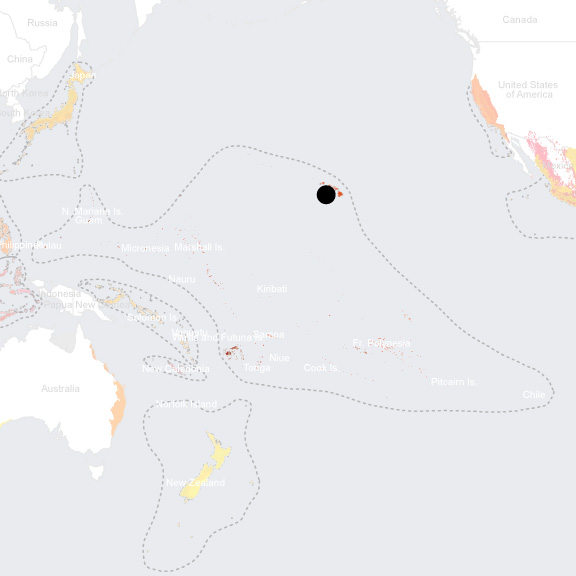

- Global Location plan: 21.31oN, 157.86oW [1]

- Hotspot: Polynesia-Micronesia

- Population 2015: 848,000

- Projected population 2030: 987,000

- Mascot Species: the Monk Seal[2] (one of the most endangered species in the world; recently named Hawaii’s state mammal); the Hawaiian Goose (“Nene”) is vulnerable,[3] the Oahu Creeper (Paroreomyza maculata) possibly extinct[4] and the Oahu Nukupu’u critically endangered[5]

- Crops: [6] diversified crops (46% of Oahu’s cultivated area), followed by seed production (34%) and pineapples (16%). The island also produces Bananas, Tropical Fruits, Coffee and Papaya.

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Rhinella marina

- Eleutherodactylus coqui

- Eleutherodactylus planirostris

- Glandirana rugosa

- Lithobates catesbeianus

- Dendrobates auratus

- Osteopilus septentrionalis

- Eleutherodactylus martinicensis

Mammals

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Rattus exulans

- Peponocephala electra

- Tursiops truncatus

- Stenella longirostris

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Mus musculus

- Grampus griseus

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Lontra canadensis

- Orcinus orca

- Lasiurus cinereus

- Lagenodelphis hosei

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Indopacetus pacificus

- Stenella attenuata

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Kogia sima

- Antilocapra americana

- Feresa attenuata

- Neomonachus schauinslandi

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Balaenoptera physalus

- Kogia breviceps

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Polynesia-Micronesia biodiversity hotspot contains at least 4,500 islands, including all the islands of Micronesia and Polynesia, plus Fiji. Scattered across the Pacific Ocean, it has varied ecosystems – ranging from rainforests, temperate forests, wetlands, and savannas – and is characterized by high levels of biodiversity and endemism. Local people are highly dependent on the natural land and marine resources. It is one of the most threatened areas in the world, particularly by invasive species. [7]

Species statistics [8]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~5,330 |

>58% |

- Hawaiian honeycreepers ( Drepanididae ) |

|

Bird |

~290 |

~55% |

|

|

Mammals |

16 |

~16% |

- Endangered Hawaiian monk seal ( Monachus schauinslandi ) |

|

Reptiles |

>60 |

~50% |

- saltwater crocodile ( Crocodylus porosus ) |

|

Amphibians |

DD |

DD |

- only three native ranid frogs, endemic to Fiji and Palau respectively |

|

Freshwater Fishes |

~100 (adults live in freshwater) |

~20% |

- no strictly native freshwater fishes - Goboid fishes ( Gobiidae and Eleotridae ) |

Only 21 percent of the original vegetation cover of the hotspot remains intact. Increasing human population, commercialization, monetization, tourism, and globalization lead to loss of traditional knowledge and ill resource management. Invasive species are the major problem in the hotspot; they menace about three quarters of all the threatened species. Habitat alteration and loss are caused by agriculture and logging. Construction of roads for such economic activities also results in the spread of invasive predators. Other destructive factors include hunting, sea-level rise and extreme weather events induced by Climate Change. [9]

CEPF invested US$7 million from 2008 to 2013 in the hotspot. The strategy emphasized the need to prevent, control, and eradicate invasive species in 60 Key Biodiversity Areas. The funds promoted community-based projects, and almost 40 percent of them contributed to enhancing existing protected areas. [10]

Hawaii Tropical Moist Forests

The Hawaii Tropical Moist Forests ecoregion is comprised of mixed mesic forests (about 750-1,250 m elevation), rainforests (higher than 1,700 m), wet shrublands, and bogs. Koa ( Acacia spp. ) and ‘Ohi’a lehua ( Metrosideros spp .) are common dominant canopy trees. Mosses, tree ferns, and Hawaii’s three native orchids also prevail. This ecoregion was a center for adaptive radiation. The mesic forests are the richest environment for endemic tree species and important bird habitat, including the honeycreepers, the Hawaiian hawk, crows, and thrushes. [11]

Forests on lowland and foothills have been largely eliminated. Some relatively large blocks of montane forest still exist on larger islands but are also degraded. Main threats come from feral ungulates, introduced weed species, trampling hikers, recreational activities, and urban development.

[12]

At present, 13 percent of the ecoregion is protected, which has a 7.4 percent terrestrial connectivity. Most of the protected areas are located on the Big Island.

[13]

Hawaii Tropical Dry Forests

The Hawaii Tropical Dry Forests typically occur on the leeward side of the main islands and once covered the summits of the smaller islands. The canopy can exceed 20 m in height in montane areas. Most of the native vegetation are either seasonal or sclerophyllous to some degree. Around 22 percent of Hawaiian plant species grow within this ecoregion, including some specialist species such as the native hibiscus trees. The original dry forests have been reduced by more than 90 percent, and what is left is highly fragmented. Burning, expansion of agriculture and pasture are destroying the remaining habitat. Other threats come from introduced plants, rats, seed-boring insects, and grazing livestock. [14] Today, 16 percent of the ecoregion is under protection and 13.34 percent terrestrially connected. [15]

Hawaii Tropical Low Shrublands

The Hawaii Tropical Low Shrublands ecoregion comprises all of the northwestern Hawaiian Islands, the lowest leeward slopes of the higher islands, and on all but the summit regions of Lana’I, Kaho’olawe, and Ni’ihau. Non-tree plant diversity is high (more than 200 species) and highly endemic (over 90 percent); tree diversity is relatively low. More than 90 percent of the low shrublands are already lost to development or alien vegetation. Fire, weed, invasions, feral grazing animals (e.g. goats and deer), and continuing development are the main threats. [16] Currently, 10 percent of the ecoregion is protected, and 6.9 percent is terrestrial connected. [17]

Hawaii is a hotspot of endemism; more than 90% of the state’s species are endemic. [18] Sadly, many of these species are in existential peril; the state is often referred to as the “endangered species capital of the world.” [19] This is fitting as the islands’ endangered species are so numerous that they represent 38% of endangered species listed by the Fish and Wildlife Service for the entirety of the United States.

Honolulu, Hawaii’s biggest city, is located on the island of Oahu, which is similar to most of the Hawaiian islands contains fragments of three ecoregions: the Hawaiian tropical moist forests, the Hawaiian tropical dry forests, and the Hawaiian low shrublands. The tropical moist forests, at the center of the island and in the North-East, include wetlands, mixed mesic forests, and rain forests. [20] Tropical dry forests, which surround the moist forest, have been reduced by 90% in Hawaii. Both forest ecoregionas are highly fragmented, and have largely been depleted in lower areas, leaving few extensive contiguous areas of montane forest. [21] Tropical low shrublands cover the remaining area of the island in the South-West, and have been similarly degraded as only 10% of their original extents remain intact. More than 90% of non-tree plants in this ecoregion are endemic. [22]

The endangered species in Hawaii are primarily plants and birds, followed by snails, spiders, and a few mammals [23] Introduced species are a major threat to endemic and indigenous Hawaiian plants and animals; carnivorous snails are just one example of introduced species wreaking havoc on endemic species, such as the critically endangered Oahu Tree Snail ( Psittirostra psittacea ). Hawaiian Monk Seals ( Neomonachus schauinslandi ) are endangered due mainly to food limitations resulting from changes in environmental conditions, competition with other species and the remnant impact of fisheries. Notable endangered bird species present on Oahu include the Oahu Elepaio ( Chasiempis ibidis ), the reintroduced Hawaiian duck ( Anas wyvilliana ), and the possibly extinct Ōʻū ( Psittirostra psittacea ) . Many plant species of the genus Cyanea are critically endangered and endemic to Oahu, including Cyanea grimesiana . Other Oahu-endemic and critically endangered plants include Oahu lobelia ( Lobelia oahuensis ), Dubautia herbstobatae , and Neraudia angulata . [24]

These species are threatened by human development, recreational activities, fires, and climate change, which is especially problematic for those that already live in elevated areas. The biggest threat to native wildlife is the proliferation of non-native invasive species, including habitat-modifiers, predators, competitors, diseases, and disease carriers. For instance, disease-carrying mosquitoes have heavily affected bird populations in low and increasingly high altitudes due to climate change. Botulism threatens water birds while toxoplasmosis has heavily affected Hawaiian Goose ( Branta sandvicensis ) and Hawaiian Monk Seal ( Neomonachus schauinslandi ) populations. Weeds like African Fountain Grass ( Pennisetum setaceum ), West Indian Lantana ( Lantana Camara ), and Molasses Grass ( Melinis minutiflora ) compete with native flora for soil nutrients, while livestock and feral goat, deer and pigs continuously threaten it with consumption, trampling, or grazing. [25]

Environmental History

The first Polynesian settlers arrived in the Hawaiian Islands between 500 and 760AD. Their use of burning for agriculture was the first major reducer of dry forest cover. [26] The archipelago was occupied by Tahitians around 1000, and later visited by American whalers. Whaling became the driver of the Hawaiian economy, causing great change and expansion in agriculture to meet the demands of sailors. After a few failed western occupation attempts, the Kingdom of Hawaii was overthrown in favor of a short-lived republic that ceased when the United States annexed Hawaii in 1898. [27]

Whaling boats introduced mosquitos to the islands; these became a vector for diseases like avian malaria which devastated bird populations. [28] Invasive animal species have been introduced to the islands throughout the islands’ human history. The feral pigs present today descend from domesticated Polynesian pigs introduced early on, as well as from European and Asian pigs introduced much later. [29] Similarly, goats introduced by Polynesian settlers eventually became feral; today their grazing, trampling, selective feeding habits and nonnative seed-dispersion pose a significant threat to native ecosystems. [30] Ironically, Indian Mongooses were introduced in 1883 to control the rat populations in sugar cane fields, and are now posing a threat to Hawaiian birds. [31]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Most of the indigenous woodlands on Oahu’s lowlands have been converted to other land uses, leaving very limited indigenous forest cover intact (except for the highly fragmented montane moist forests). On the east side of Honolulu, the urban fringe is made up of residential areas that seep in between the crests of the watershed and occasionally expand atop the hills. On the west side, vast rural areas extend from the city to the island’s north-western waterfront, dividing the forest cover completely. Multiple Highways connect Honolulu to the north coast, further fragmenting the remaining forests. [32]

The Hawaii state Department of Land and Natural Resources elaborated the Hawaii State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP), which identifies Oahu as a major entry point for invasive species on Hawaii. For instance, the island is infested with Yellow Crazy Ants ( Anoplolepis gracilipes ), which outcompete other species by dominating local resources thanks to their vast supercolonies. The SWAP also describes phenomena like seal-level rise, storms and wildfires as major threats to native flora. Human activity is also a direct cause of biodiversity loss, through development and urbanization, recreational overuse and pollution. Administrative issues such as poor information management and weak enforcement due to limited funding are also major obstacles to biodiversity conservation. [33]

Hawaii is located in the middle of the North Pacific gyre, a system of strong circular currents that leads to the formation of patches of floating waste, posing a major problem for Hawaiian biodiversity. Indeed, the marine life and seabirds often ingest the debri that washes up on the island’s shores or get entangled in it. [34] Additionally, plastic waste caries numerous pathogens like Halofolliculina corallasia , which was found in Hawaii in 2010, where it threatens corals with a disease called skeletal eroding band. [35]

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

The Island of Oahu has a density of 1596/km2, and its population grew an average of 0.69% per year between 2007 and 2017. [36] A 2016 Study by Thomas Laidley shows that although Honolulu had the fourth highest Sprawl Index among American cities in 2010, it is also the city whose sprawl was most reduced between 2000 and 2010, due to the strict enforcement of zoning policies. [37] Indeed, neither the residential areas to the East nor the fields to the West of Honolulu have expanded further into the forest cover in the past twenty years. In fact, satellite imaging shows the conversion of fields to forest cover in on Oahu’s North Western coast between 2008 and 2016. [38]

City Policy/Planning

Development Plan

Although Oahu does not have long term vision plan, the state wrote the Hawaii 2050 Sustainability Plan in 2008, emphasizing “smart growth” and the densification and vertical development of urban centers rather than sprawl. The Plan also mentions the intended development of a Quality Growth Policy by the state Office of Planning, though this project has not been realized to date. [40]

The Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources enforces strict policies concerning development projects. For instance, landowners and developers who wish to build in the county are required to obtain an Incidental Take License, through which the department authorizes projects that could harm local biodiversity. They also require a Habitat Conservation Plan, which seeks to minimize and offset the negative impacts of the construction project on biodiversity. [41]

Zoning

The Oahu Metropolitan Planning Organization drew the Oahu urban growth boundary (UGB), which divides the the island into districts designated for specific land uses and functions. [42] The process to amend the border is lengthy and costly, making land conversions quite difficult. [43] The policies of the Oahu Metropolitan Planning Organization only allow for land conversions within the existing UGB, acknowledging that completely stopping urban growth could lead to higher housing prices, causing serious social issues. [44]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

National

The United States did not sign the Convention on Biological Diversity. Instead, conservation efforts are guided by the country’s Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973, which defines “endangered” as a higher risk level than “threatened,” rather than a subcategory. [45]

Regional

Hawaiian laws forbid any destructive interaction with species listed on the ESA; transgressors can be fined $5,000 for harming threatened species and $10,000 for harming endangered species. [46] An Endangered Species Recovery Committee operates within the Division of Forestry and Wildlife of its Department of Land and Natural Resources. This unit reviews Habitat Incidental Take Licenses and Conservation Plans, which help prevent or mitigate the damage that development projects cause to biodiversity. The committee provides incentivizes for landowners to protect endangered species , namely by reviewing Safe Harbor Agreements, which facilitate conservation efforts for landowners . [47]

In addition to these laws and incentives, the State of Hawaii 2050 Sustaina bility Plan addresses biodiversity conservation through its goals although it does not provide any spatial planning . Indeed, the third goal of the plan, “Environment and Natural Resources,”calls for improved protection and management of all habitats on the islands, as well as funding to raise awareness around conservation. Additionally, the plan addresses the need for management solutions to natural hazards like sea-level rise and erosion, and for a better ecosystem mapping and measurement system. [48]

The aforementioned 2015 State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) gives a detailed account of endangered species, threats, and necessary solutions. Its many goals include successful protection and restoration of habitat, pest control, improved information management and better education around biodiversity. In terms of administration, the plan suggests policy changes, cooperation efforts, and improved funding. [49]

Local

The SWAP makes recommendations specific to Oahu, starting with land management through acquisition and cooperative agreements with landowners. Other recommendations include reintroducing species to areas deemed safe, improving fire-suppression measures, and combating invasive species. The latter is addressed by a three-tiered approach. Increased inspections at entry points such as airports would allow for better prevention of infestations. Early detection of invasive species would allow the county to engage in a rapid response to control species like the Little Fire Ant, which is present on other Hawaiian islands. Finally, control and eradication might be employed to reduce the numbers of species such as ants, carnivorous snails and mongoose. Some invasive species are controlled through physical interventions, including New-Zealand tested predator fencing and the Aquatic Supersucker for algae. [50] Finally, the SWAP emphasizes the need to improve cooperative efforts, awareness, and information systems through databases and species-specific studies. [51]

The Honolulu City and County’s Department of Land Management created the Clean Water and Natural Lands Fund in 2006 to allow the city to purchase sensitive areas for conservation. For instance, the fund enabled the purchase of the Kānewai Spring, which features a mix of fresh and saltwater that harbors many unique species. [52]

Protected Areas

Honolulu county includes many protected areas, which are managed by the state’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DFW), the US Fish and Wildlife Services and the US Marine Corps. The DFW forest reserves cover over 2,700km2 spread across the island, mainly over the Ko’olau and Waianae mountain ranges. Smaller protected areas include the Kawai Nui and Hāmākua complex, which has undergone DFW habitat restoration efforts including native species planting and invasive plant and animal removal. The DFW does not have a management plan for the Second largest protected area, Pahole Natural Area Reserve, although it does engage in invasive species control. The Marine Corps manages the third main protected area, the Nu‘upia Pond Wildlife Management Area, in accordance with the Integrated natural Resources Management Plan of the Department of Defense, through wetland improvement, species monitoring, and invasive plant and animal control. [53]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

Many non-governmental organizations contribute to habitat conservation and restoration. Among these, the Ko’olau Mountains Watershed Partnership conducts weed control, fence line construction, bio surveying and community outreach. [54] Other organizations such as the Hawaiian Legacy Reforestation Initiative focus on reforestation in projects like the Gunstock Ranch Legacy Forest, on the north shore of Oahu. [55] More administrative groups like the Conservation Council for Hawai‘i or the Coordinating Group on Alien Pest Species work on raising biodiversity concerns on a political level, and on fostering collaboration between the government and non-governmental organizations. [56] The Hawai’i Conservation Alliance is another politically-oriented organization that works closely with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature to produce resolutions and recommendations to improve biodiversity protection in the State. [57]

Public Awareness

Awareness on conservation in Hawaii is high, and biodiversity is an integral component of the state’s cultural identity and of tourism in the archipelago.

Conclusion

Although the lowland ecosystems within the *** and ** ecoregion have been mostly eliminated, the urban growth boundary enforced by the city of Honolulu seems to be an effective measure for containing urban growth and preventing further destruction of these unique ecosystems. Given this, alien invasive species pose the predominant threat to local biodiversity, though human development and recreational activities still continue to threaten local ecosystems.

Local laws prohibiting the harm of threatened or endangered species are enforced strictly by the local government, and both governmental and non-governmental initiatives are working to restore some of the damaged forest cover of Oahu.

Addendum

[TODO]

Current Mayor/People in Power

Oahu branch of the Hawaii Division of Forestry and wildlife: (808) 973-9778

[2] Tracy Gladden, “Hawaiian monk seal is the new state mammal,” Hawaii News Now, http://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/story/8483697/hawaiian-monk-seal-is-the-new-state-mammal (Accessed June 27, 2018).

[3] The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, “Branta sandvicensis,” http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22679929/0 (accessed May 25, 2018)

[4] Center for Biological Diversity, “A Wild Success: A Systematic Review of Bird Recovery Under the Endangered Species Act,” June 2016

[5] Birds of NorthAmerica, “Oahu Nukupuu,” https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/nukupu3/conservation (accessed May 30, 2018)

[7] CEPF. “Polynesia-Micronesia.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/polynesia-micronesia.

[8] CEPF. “Polynesia-Micronesia - Species.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/polynesia-micronesia/species.

[9] CEPF. “Polynesia-Micronesia - Threats.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/polynesia-micronesia/threats.

[10] CEPF. “Polynesia-Micronesia.” Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/polynesia-micronesia.

[11] “Hawaii Tropical Moist Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0106.

[12] “Hawaii Tropical Moist Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0106.

[13] “Hawaii Tropical Moist Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/70106.

[14] WWF. “Hawaii Tropical Dry Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0202.

[15] “Hawaii Tropical Dry Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/70202.

[16] WWF. “Hawaii Tropical Low Shrublands | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0702.

[17] “Hawaii Tropical Low Shrublands.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/70702.

[18] WWF, “The Endangered Species Capital of The World” http://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/teacher_resources/best_place_species/current_top_10/Hawai’i.cfm (accessed May 25, 2018)

US Fish & Wildlife Service, “Generate Species Count,” https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/pub/adHocSpeciesCountForm.jsp (accessed June 15, 2018)

[19] WWF, “The Endangered Species Capital of The World” http://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/teacher_resources/best_place_species/current_top_10/Hawai’i.cfm (accessed May 25, 2018)

US Fish & Wildlife Service, “Generate Species Count,” https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/pub/adHocSpeciesCountForm.jsp (accessed June 15, 2018)

[20] WWF, “Hawai’i tropical moist forests,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0106 (accessed June 13, 2018)

[21] WWF, “Hawai’i tropical dry forests,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0202 (accessed June 13, 2018)

[22] WWF, “Hawai’i tropical low shrublands,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0702 (accessed June 13, 2018)

[23] Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, “Hawai’i State Wildlife Action Plan,” 2015

[24] IUCN, “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species,” http://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed June 13, 2018).

[25] WWF, “Hawai’i tropical low shrublands,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0702 (accessed June 13, 2018)

WWF, “Hawai’i tropical dry forests,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0202 (accessed June 13, 2018)

WWF, “Hawai’i tropical moist forests,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0106 (accessed June 13, 2018)

Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, “Hawai’i State Wildlife Action Plan,” 2015

[26] WWF, “Hawai’i tropical dry forests,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/oc0202 (accessed June 13, 2018)

[27] HawaiiHistory.org, “Whaling Industry,” http://www.hawaiihistory.org/index.cfm?PageID=287&returntonameShort+Stories (accessed June 13, 2018)

[28] Native Voices, “Timeline,” https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/694.html (accessed May 25, 2018)

[29] Anna Linderholm, et al., “A novel MC1R allele for black coat colour reveals the Polynesian ancestry and hybridization patterns of Hawai’ian feral pigs,” Royal Society Open Science 3: 160304

[30] Mark Chynowth, Christopher A. Lepcyk & Creighton M. Litton, “Feral Goats in the Hawai’ian Islands: Understanding the behavioral Ecology of Nonnative Ungulate with GPS and Remote Sensing Technology,” 24th Vertebrate Pest Conference, 2010

[31] Hawai’i Invasive Species Council, “Mongoose,” https://dlnr.Hawai’i.gov/hisc/info/invasive-species-profiles/mongoose/ (accessed May 30, 2018)

[32] EARTH

[33] Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, “Hawai’i State Wildlife Action Plan,” 2015

Joleah Lamb, “11 Billion Pieces of Plastic Brings Disease Threat to Coral Reefs,” Down to Earth 29 (2018)

Wet Tropics Management Authority, “What are yellow crazy ants?”

https://www.wettropics.gov.au/yellow-crazy-ants (accessed June 14, 2018)

[34] Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, “Hawai’i State Wildlife Action Plan,” 2015

Jareen Imam, “Hawaii has a serious trash problem — and it's coming on ocean waves,” CNN (June 3, 2016), https://www.cnn.com/2016/06/03/us/hawaii-island-trash-problem-irpt/index.html

[35] Caroline Palmer & Ruth Gates, “Skeletal eroding band in Hawaiian corals,” Coral Reefs 29, no. 2 (2010), 469

Miriam Goldstein, “The scariest inhabitant of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is not what you think,” Deep See News (May 14, 2014), http://www.deepseanews.com/2014/05/the-scariest-inhabitant-of-the-great-pacific-garbage-patch-is-not-what-you-think/

[36] World Population Review, “Hawai’i Population 2018,” http://worldpopulationreview.com/states/Hawai’i-population/ (accessed May 30, 2018)

Hawai’i Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism, “Data Warehouse,”

http://dbedt.Hawai’i.gov/economic/datawarehouse/ (accessed May 30, 2018)

[37] http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2169/doi/pdf/10.1177/1078087414568812

[38] EARTH

[39] Honolulu City and County, “Honolulu City Council,” https://www.honolulu.gov/council (accessed July 1)

[40] Hawai’i 2050 Sustainability Task Force, “Hawai’i 2050 Sustainability Plan,” 2008

[41] State of Hawai’i, Division of Forestry and Wildlife, “Habitat conservation plans,” https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/wildlife/hcp/ (accessed May 25, 2018)

[42] Hawai’i Statewide GIS Program, “State of Hawai’i Land Use District Boundaries Map,” January 2018, http://histategis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=b843c728b4cb4333b1df015fdaa84104

[43] State of Hawai’i Land Use Commission, “Boundary Amendment Procedures,” http://luc.Hawai’i.gov/about/district-boundary-amendment-procedures/ (accessed May 30, 2018)

[44] Oahu Metropolitan Planning Organization, “Land Development, Urban Growth, and Transportation,” http://www.oahumpo.org/land-development-urban-growth-and-transportation-2/ (accessed June 15, 2018)

[45] United States Congress, "Endangered Species Act,” 1973

[46] Our Hawai’i Environmental Law Online, “Chapter 195D: Conservation of Aquatic Life, Wildlife and Land Plants,” http://www.Hawai’i.edu/ohelo/statutes/HRS195D/HRS195D.htm (accessed May 25, 2018)

[47] State of Hawai’i, Division of Forestry and Wildlife, “Endangered Species Recovery Committee,” https://dlnr.Hawai’i.gov/wildlife/esrc/ (accessed May 25, 2018)

[48] Hawai’i 2050 Sustainability Task Force, “Hawai’i 2050 Sustainability Plan,” 2008

[49] Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, “Hawai’i State Wildlife Action Plan,” 2015

[50] Department of Land and Natural Resources: Divison of Aquatic Invasive Species, “Super Sucker,” https://dlnr.Hawai’i.gov/ais/invasivealgae/supersucker/ (accessed May 30, 2018)

[51] Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, “Hawai’i State Wildlife Action Plan,” 2015

[52] City and County of Honolulu, “Department of Land Management,” http://www.honolulu.gov/dlm/home.html (accessed May 25, 2018)

[53] Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, “Hawai’i State Wildlife Action Plan,” 2015

[54] The Ko‘olau Mountains Watershed Partnership, “Where we work,” http://koolauwatershed.org/where-we-work/ (accessed May 25, 2018)

[55] Hawai’ian Legacy Reforestation Initiative, “Return of the Hawai’ian Forest,” https://legacytrees.org/ (accessed May 30, 2018)

[56] Conservation Council for Hawai’i, “About Us,” http://www.conservehi.org/content/about_us.htm (accessed May 30, 2018)

Coordinating Group on Alien Pest Species, “E Komo Mai!” http://www.cgaps.org/ (accessed May 30, 2018)

[57] Hawai’i Conservation Alliance, “Cultivating Aloha for Our Lands and Seas,” http://www.Hawai’iconservation.org/ (accessed May 30, 2018)

[58] http://honolulu-cchnl.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/ca54a3178bfd4d8f8e6c91f217c8e65a_4?geometry=-158.867%2C21.11%2C-156.781%2C21.815&mapSize=map-maximize