Houston, United States

- Global Location plan: 29.75oN, 95.37oW

- Population 2015: 5,638,000

- Projected population 2030: 6,729,000

- Mascot Species: Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii),

- Primary Crops: nursery crops, hay, Christmas trees, rice, and corn.[1]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Lithobates sphenocephalus

- Ambystoma texanum

- Ambystoma talpoideum

- Pseudacris fouquettei

- Anaxyrus punctatus

- Lithobates clamitans

- Anaxyrus fowleri

- Incilius nebulifer

- Anaxyrus woodhousii

- Dryophytes versicolor

- Pseudacris crucifer

- Pseudacris streckeri

- Eleutherodactylus cystignathoides

- Eleutherodactylus cystignathoides

- Gastrophryne olivacea

- Amphiuma tridactylum

- Desmognathus auriculatus

- Necturus beyeri

- Siren intermedia

- Dryophytes cinereus

- Notophthalmus viridescens

- Ambystoma tigrinum

- Lithobates palustris

- Lithobates catesbeianus

- Anaxyrus houstonensis

- Acris crepitans

- Pseudacris clarkii

- Dryophytes chrysoscelis

- Notophthalmus viridescens

- Scaphiopus couchii

- Dryophytes squirellus

- Plethodon albagula

- Gastrophryne carolinensis

- Dryophytes chrysoscelis

- Lithobates areolatus

- Lithobates grylio

- Scaphiopus hurterii

- Ambystoma opacum

- Eurycea quadridigitata

- Anaxyrus speciosus

- Ambystoma maculatum

Mammals

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Tadarida brasiliensis

- Reithrodontomys fulvescens

- Sigmodon hispidus

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Reithrodontomys montanus

- Sylvilagus aquaticus

- Conepatus leuconotus

- Spilogale putorius

- Ursus americanus

- Ursus americanus

- Lasiurus borealis

- Eubalaena glacialis

- Odocoileus virginianus

- Lasiurus cinereus

- Nyctinomops macrotis

- Geomys attwateri

- Geomys breviceps

- Peponocephala electra

- Tursiops truncatus

- Ondatra zibethicus

- Stenella longirostris

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Sciurus carolinensis

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Pecari tajacu

- Cryptotis parva

- Mus musculus

- Stenella clymene

- Grampus griseus

- Chaetodipus hispidus

- Lepus californicus

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Lontra canadensis

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus

- Mephitis mephitis

- Orcinus orca

- Lasiurus intermedius

- Dasypus novemcinctus

- Taxidea taxus

- Mesoplodon europaeus

- Myotis velifer

- Lasionycteris noctivagans

- Lasiurus seminolus

- Lynx rufus

- Delphinus delphis

- Oryzomys palustris

- Microtus ochrogaster

- Sciurus niger

- Bassariscus astutus

- Didelphis virginiana

- Peromyscus gossypinus

- Lagenodelphis hosei

- Reithrodontomys humulis

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Stenella frontalis

- Steno bredanensis

- Procyon lotor

- Nycticeius humeralis

- Neotoma floridana

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Neovison vison

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Vulpes vulpes

- Blarina carolinensis

- Microtus pinetorum

- Ictidomys tridecemlineatus

- Canis latrans

- Peromyscus leucopus

- Scalopus aquaticus

- Glaucomys volans

- Stenella attenuata

- Castor canadensis

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Kogia sima

- Baiomys taylori

- Eptesicus fuscus

- Feresa attenuata

- Perimyotis subflavus

- Peromyscus maniculatus

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Kogia breviceps

- Corynorhinus rafinesquii

- Mustela frenata

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

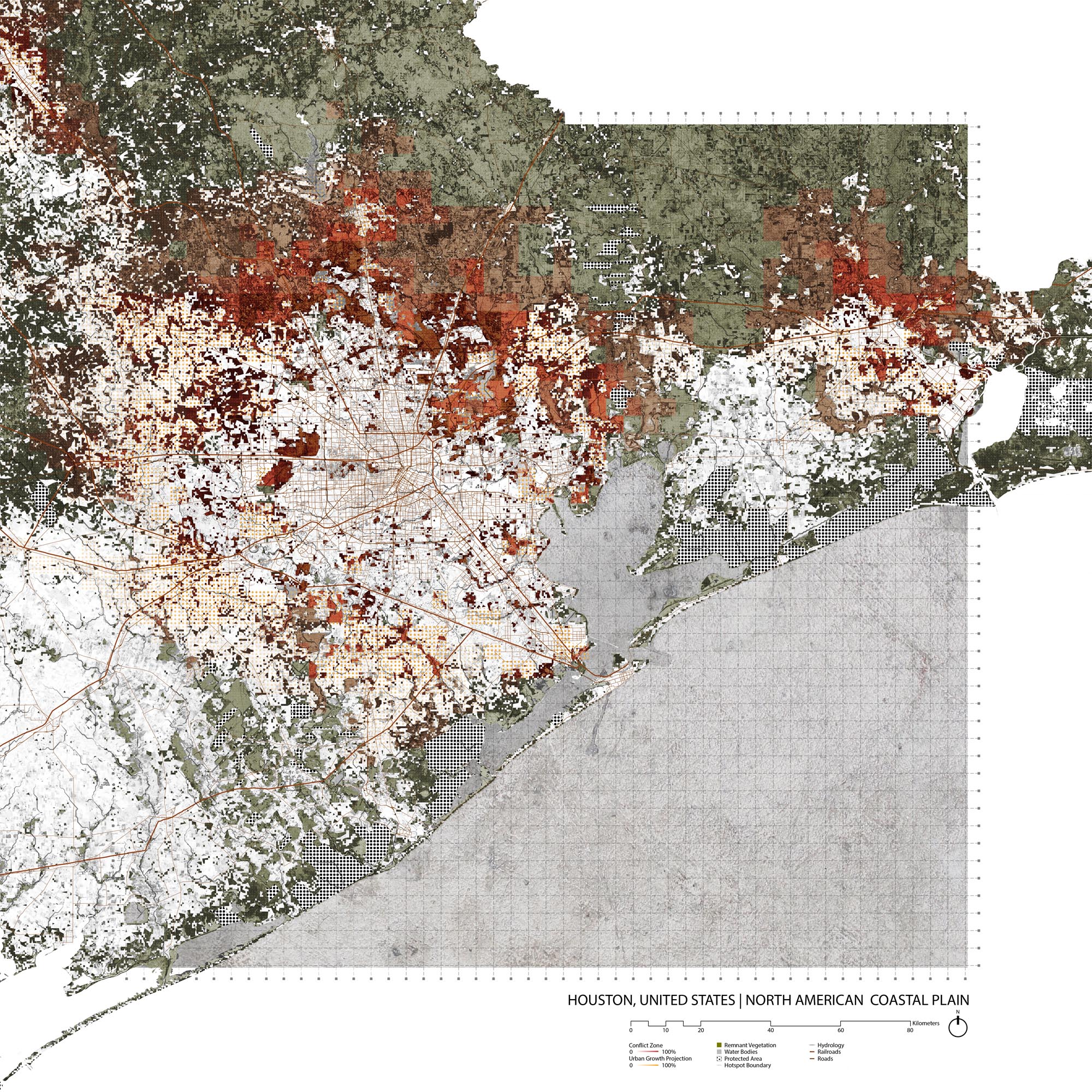

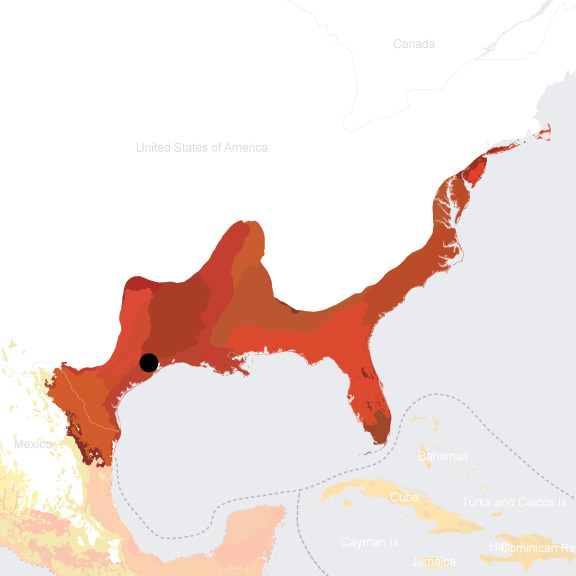

The Houston metropolitan area is primarily within the Western Gulf Coastal Grasslands Ecoregion, but the suburban areas also extend out into the Piney Woods Forests Ecoregion. Both ecoregions are part of the North American Coastal Plain Hotspot.

Th is region was recognized as a biodiversity hot spot relatively late ( it is the 36 th and most recent ly designated hotspot, as of 2016 ) because of its low level of geographic variety and elevational change relative to other hotspots. The hotspot stretches from southeastern Massachusetts down along the Eastern Seaboard, along the Gulf of Mexico, and j ust into northern ea stern Mexico. This hotspot is a fire-dependent zone as many of the plant and animal species here rely on natural burns and some even evolved serotinous features. [2]

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

DD |

~30% |

|

|

Birds |

>270 |

2.2% |

|

|

Mammals |

306 |

114 |

|

|

Reptiles |

293 |

113 |

|

|

Amphibians |

122 |

57 |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

424 |

138 |

|

European settlers converted more than 85 percent of the savannas and woodlands within the Northern American Coastal Plain to non-native plantations, radically reducing the region's levels of biodiversity. [4] Today, the primary threats to the hotpot include fire suppression, deforestation for agricultural and infrastructural developments, water pollution from these developments, pesticides, and climate change . [5]

Western Gulf Coastal Grasslands Ecoregion

The Western Gulf Coastal Grasslands ecoregion extends along the Gulf of Mexico from Louisiana and Texas, west of the Mississippi Delta, south into Mexico and just past the Laguna Madre. Semiarid climate of less than 300 mm of precipitation per annum , sandy loam soils, tropical storms, and fire-dependent ecosystems distinguish the area. Important landscapes include tallgrass prairies, “resacas” (a type of oxbow lake), freshwater marshes, and intertidal wetlands. Emergent palustrine wetlands are amongst the most threatened in this ecoregion. [6]

About 700 kinds of vertebrates occur in th is ecoregion, and many of them are threatened. In 1988, 86 species were listed as endangered or threatened. For example, the Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle ( Lepidochelys kempii ), the smallest sea turtle and the most endangered today , suffered rapid decline from over 40,000 nests in 1942 to fewer than 1,500 by the 1990s. [7]

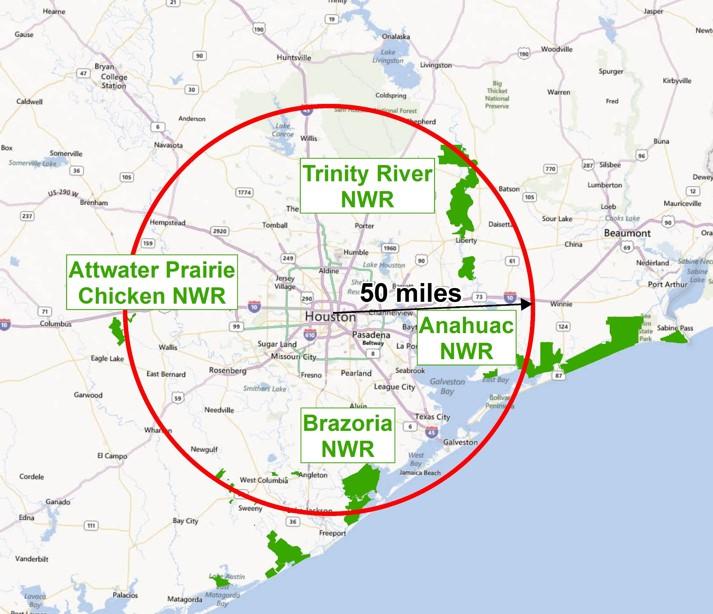

By 1991, l ess than one percent of the original grasslands remain ed in pristine condition. Land c onversion to agricultur e had caused the greatest losses. Overgrazing, woody encroachment, f ragmentation of left habitats into marketable ranchettes, channelization projects, and the suppression of natural fires also caused significant negative effects . Near expanding metropolitan areas such as Houston, urbanization and suburban sprawl lead to severe problems. [8] The National Wildlife Refuge System has purchased a series of important sites for the protection of waterfowl. The refuges around the Houston metropolitan area include the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, Moody National Wildlife Refuge, Attwater’s Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge, Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge, San Bernard National Wildlife Refuge, Big Boggy National Wildlife Refuge . [9] At present, the Western Gulf Coastal Grasslands are 12% protected , and 6.84% terrestrially connected. [10]

Location of National Wildlife Refuges in the Greater Houston Metropolitan area

Piney Woods Forests Ecoregion

The Piney Woods Forests ecoregion stretches across eastern Texas, northwestern Louisiana, and southwestern Arkansas. It includes what is commonly known as the Big Thicket region of east Texas. The interaction of moisture and fire frequency determines vegetation structure and composition in the region. Dominant plant species include long-leaf pine ( Pinus palustris ), short-leaf pine ( Pinus echinata ), and loblolly pine ( Pinus taeda ). In some areas oaks and hickories are mixed in with pines. Yaupon ( Ilex vomitoria ) and flowering dogwood ( Cornus florida ) are common understory plants. [11]

Only about 3 percent of the remaining habitat is considered intact. Urban development and logging were the major causes of habitat loss. Much of the ecoregion have been converted to plantations. Today, fire suppression is the main threat to biodiversity, as local species are dependent on burns. [12] At present, 3 percent of the ecoregion is protected, and only 1.27 is considered terrestrial connected. [13]

Environmental History

This section is currently lacking indigenous history

Houston was founded by brothers Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirkby Allen in 1836 . [14] The proximity to the Galveston Bay system , which is connect ed to Houston by the Buffalo Bayou, attracted the brothers to invest in and develop the area. In 1842, the Congress of the Republic of Texas approved digging out the Buffalo Bayou to make way for the Port of Houston leading to the development of shipping as the primary industry in the area.

Two events in the early 1900’s stim ulated intensive growth in the Houston area . The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 severely damaged the nearby trading center of Galveston, making Houston seem a geographically safer place to invest , and leading to its growing economic dominance in the region . The 1901 discovery of oil in nearby Jefferson County sparked the oil trade in Houston. [15] Oil companies began to locate their offices in Houston and refineries along the Houston Ship Channel, protected from the Gulf Coast. Houston became the largest Texan c ity by population around 1930. The prominence of the shipping and oil industry lead to the city’s growth but also to increased air and water pollution in the Greater Houston area.

The history of Houston as a sprawling metropolis started with Joseph Jay Pastoriza and his Houston Plan of Taxation, which lasted from 1912-1915 and taxed land at a much higher rate than improvements. [16] This resulted in notably higher rates of construction in an already booming city. [17] Construction continued throughout the 20th century, especially in the post - war era, with little regulation. Sprawling development has greatly reduced flood mitigation capacity; for example, 29% of natural wetland infrastructure in Harris county disappeared between 1992 and 2010. [18] The White Oak Bayou river watershed in northwest Houston lost over 70% of its wetlands.

Flooding is a huge part of the city’s history. After damaging floods hit Houston in 1929 and 1925, the state legislature created the Harris County Flood Control District in 1937 to build flood infrastructure. [19] In the decades following, the Addicks and Barker reservoirs were built and three bayous were either widened or converted to concrete culverts. Flooding events are more frequent and more intensive due to the replacement of vast wetland areas with non-permeable surfaces such as concrete. The Houston metro area experienced intensive flooding in 2001, 2015, 2016, and 2017 , including massive flooding as a result of Hurricane Harvey which is tied with Hurricane Katrina causing the most economic damage of any hurricane in American history.

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Less than one percent of the entire ecoregion ’s natural vegetation remains undisturbed. [20] The most major threats to biodiversity in this ecoregion are overgrazing, invasive species, natural fire suppression, and urban expansion.

Scarcity of many naturally occurring species is a result of overgrazing the land. [21] Many grasses adapted to bison grazing cannot tolerate cattle grazing and thus become replaced by exotic plants. Invasive species are able to overtake prairie land because of agricultural development. [22] Abandoned farmland, lacking its evolved biodiversity, is susceptible to being overtaken rapidly by exotic plants. Although these plants could be managed by fire, their natural fire ecology has also been stymied by development. Using fire as a management tool also does not guarantee habitat restoration. [23]

Urban and industrial expansion also pose a significant threat to Houston’s ecosystem and public health. Land conversion of natural habitat , especially of wetlands, ha s fragmented and undermined ecosystems, while also endangering the city by undermining the areas’ natural flood mitigation zones. The industrial history of Houston as a shipping, oil, and chemical center has left a toxic physical legacy . The Greater Houston Area has more than a dozen Superfund sites, or industrial areas highly polluted from hazardous waste that requires years of cleanup. [24] Floods themselves cause further environmental damage by spreading toxic chemicals, sewage, debris, and waste to the population and ecosystems. [25]

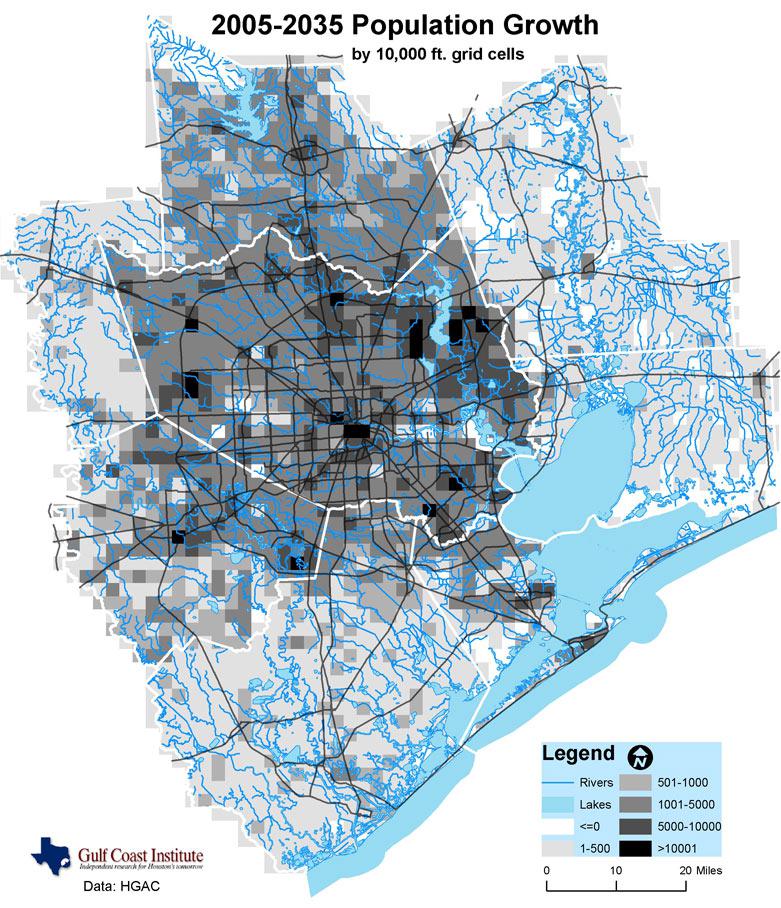

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Harris County, especially Houston, is one of the fastest growing areas in the United States. [26] The population of Houston is projected to increase by over a million new residents between 2016 and 2030. The growth is predicted to be spread out across the Greater Houston area rather than being concentrated within the Houston city limits. [27] Houston’s growth is formal but unplanned and has been characterized by low density development due to low land prices and lack of geographically restricting features. [28]

Source: “2035 Forecasts Houston Region Forecasts: Population and Jobs (Draft Data).” Gulf Coast Intitute. Accessed July 11, 2018. http://gulfcoastinstitute.org/2035_forecasts/main.html .

Governance

Houston is the largest city in Texas, one of the 50 federated states of the United States of America. The city has a strong mayor-council form of government, with the mayor functioning as the executive officer and the council as legislature. [29] Each of the eleven city districts elects a member of the council and five council members are elected at-large. Houston also has a city controller to certify available funds .

The Texas state government has actively fought attempts at structured land use planning, and favors decentralization of land use regulation. The state granted home rule authority to cities with populations exceeding 5,000 residents. Home rule allows cities considerable autonomy in their own policies, provided they do not contradict the state constitution or law. Within the city government, there are Super Neighborhood (SN) Councils. SN cover contiguous communities that share common geography, infrastructure, or identity. [30] The councils are made of residents and neighborhood stakeholders and work to address neighborhood concerns through plans and projects. There is also the Houston-Galveston Area Council (H-GAC), which is a non-binding, regional organization through which local governments consider issues and cooperate in solving Gulf Coast area wide problems. [31]

City Policy/Planning

Regional

The Harris County Flood Control District (the District) was created by Texas legislature in 1937 as a response to the devastating floods of 1929 and 1935. [32] Growing from its original purpose as local partner to US Army Corps of Engineers, the District devises, implements, and maintains flood control projects and infrastructure in the area. Their tree-planting program and vegetation management program enhances natural ecosystems through plantings and protection to maintain wildlife habitats and natural flood protection. [33]

Development Plan

Plan Houston is the general plan that defines successful outcomes for the city and supports strategies for development and neighborhood enhancement. [34] 32 goals are identified, organized into nine categories: people, place, culture, education, economy, environment, public services, transportation, and housing. The strategies for implementing these goals emphasizes coordination among various organizations, increasing local and global connectivity, and encouraging development. Within the goal category of the environment, “protect and conserve our resources” is the goal most connected to habitat conservatio n. Actions to achieve this goal include preserving open space for habitat preservation, encouraging reduced consumption of natural resources, limiting the city’s impact on the environment, and expanding education for conservation programs . The environmental goals are not supported with spatial data or goals, and b iodiversity i s not mentioned.

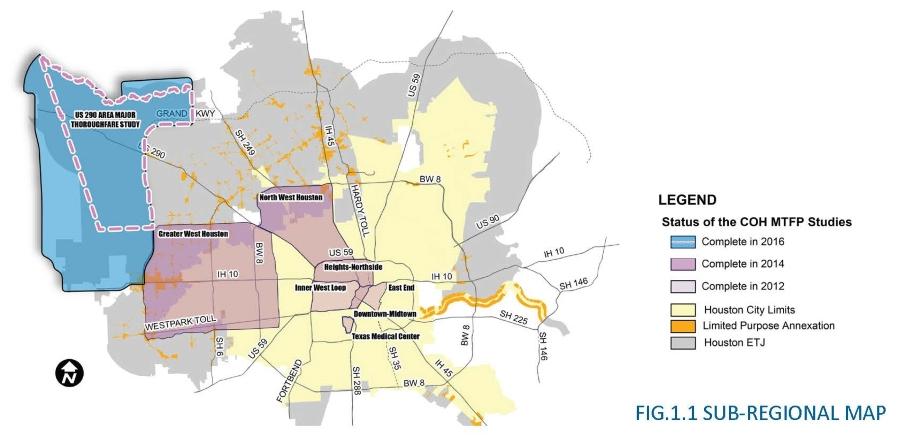

The Harris County Engineering Department published the US 290 Area Major Thoroughfare Study in June 2016, which includes the 2050 development plan. [35] The US 290 area is in the City of Houston Extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ), which is inside Houston’s Major Thoroughfare and Freeway Plan (MFTP). The study’s objectives were to develop a coordinated transportation system and address the future of the roadway networks. The study area encompasses the remnants of the Katy Prairie, a flat , low area east of the city with extensive creeks, bayous, floodplains, and floodways. Katy Prairie Conservancy preserves, established to protect the area f rom further environmental destruction and retain its biological characteristics, is within the US 290 Area. The proposed plan to the MTFP includes deleting proposed roads that go through the conservancy and instead replacing them with a loop to accommodate expected traffic flow. [36] These amendments would preserve the environmental integrity of the conservancy ’s preserves , which are among the few protected areas in the Greater Houston Area.

Source: Edwin Buitelaar, “Zoning, More Than Just a Tool: Explaining Houston's Regulatory Practice,” European Planning Studies 17, no. 7 (2009): 1049-1069

Zoning

Houston is the largest city in the United States with no zoning ordinance. Voters have rejected zoning three times in the city’s history [37] . Zoning was defeated in 1947, 1962, and 1993, albeit with support for zoning increasing each time. The referendum in 1993 had the closest margin, 48% for and 52% opposed. However, Houston does have other land-use regulations that fill some of the functions that zoning normally would. Houston does regulate lot sizes/density, building design, neighborhood layout, historic preservation, and flood control. Private restrictive covenants are also used and are enforceable by local governments. [38] Houston has regulations, including some that explicitly set zones for different uses, but no comprehensive plan. [39]

For individual subdivisions, the Planning and Development Department of the Houston government requires that a pla t be submitted, outlining how the undeveloped land will be subdivided. [40] The department reviews plats to make sure they comply with existing codes and regulations, but cannot disprove a plat for its intended use. Chapter 42 of Houston’s Code of ordinances is the city’s land development ordinance. [41]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

The United States is the only UN member state that has not ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity, and as such does not produce an NBSAP.

National

The USA belong to other international treaties regarding biodiversity, including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. [42] The Endangered Species Act of 1973 guides many current biodiversity policies. [43]

Regional and Local

The Gulf-Houston Regional Conservation Plan (Gulf-Houston RCP) is a collaborative effort by environmental, governmental, and business entities working together to promote continuity and connectivity between multiple ecosystems in the 8-county Gulf - Houston Region. [44] The collaborative includes nature-based projects in the region and assesses th e region’s most pressing ecological needs. In spring 2018, they released the 24% by 2040 Land-Use Strategy & Action Agenda. [45] The plan aims to enhance undeveloped land with nature-based infrastructure so the 8-county region has a total of 24% nature-based land use, a 15% increase from the current 9% of conserved land. The goal is to improve the region’s quality of life while also adding resiliency to the environment and economy.

The Sam Houston Greenbelt Network provides regional support f or watershed and open space planning in the core of the Gulf Houston Region. One of their main projects is the Lower Trinity River Project (LTRP). [46] The Lower Trinity River area covers five countries (Chambers, Liberty, Polk, San Jacinto, and Trinity ). The area is expe cted to have high population growth in the coming decades . LTRP focuses on increasing ecotourism, water quality and quantity, and wetland conservation to protect against possible destructive urban growth.

The Houston Parks and Recreation Department (HPARD) oversees over 37,000 acres of greenspace, including 375 developed parks. [47] Within the department , the Greenspace Management Division is in charge of Houston’s parkland, esplanades, greenspaces, and urban forests. [48] The division has 7 sections. The sections relevant to biodiversity planning include Urban Forestry, Horticulture, Houston Wild, and Lake Houston Wilderness Park. HPARD also runs a Natural Resources Management Program (NRMP) [49] . Within NRMP, there are multiple monitoring efforts conducted on natural areas within the park system to support personalized and efficient plans to manage the spaces. Management objectives include control of nonnative species, introduction of native vegetation, water quality improvement, and wildlife management.

Protected Areas

Protected a reas in the Greater Houston Area are a combination of government owned and privately owned parks.

The Katy Prairie Conservancy (KPC) was founded in 1992 to protect the prairie for both people and wildlife. [50] KPC, a non-profit organization , owns nearly 14,000 acres of prairie and protects over 3,000 acres through conservation agreements with private landowners. The goals of the conservancy focus of preserving the wildlife and habitat ecosystems to conserve important ecological functions in the face of urban growth. They also restore prairie land.

There are other smaller parks and reserves across the Houston area dedicated at least in part to wildlife conservation , including 10 acre Buffalo Bend Nature Park. [51] The City of Houston also has a list of partnerships that include parks and conservancies in the area. [52]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The Houston Parks and Recreation Department’s Natural Resources Management Program (NRMP) is currently working on a number of habitat restoration projects through they city. [53] There are prairie restoration projects in Clinton Park, Hobart Taylor Park, and Robert C Stuart Park. Strategies for these prairie projects include invasive species removal, mowing, seeding/planting, adding pollinator gardens, and educational outreach. There are also three Riparian forest restoration projects in White Oak Park, Woodland Park, and Milby Park. Strategies for forest restoration projects include invasive species removal, planting, adding educational signage, creat ing new wildlife habitats, and reducing erosion.

Lake Houston Wilderness Park , located in New Caney, Texas, is owned by the Houston Parks and Recreation Department. The Park has a Forest and Wildlife Management Plan whose intention is to support natural historic biodiversity. [54] Specifically, the plan delineates strategies to modify the forest habitat to emulate pre-settlement characteristics of the area. The biodiversity-related goals of this plan are to enhance wildlife habitat, increase ecosystem diversity, improve ecosystem health, and regenerate forests. The plan identified target habitats, species, and other characteristics associated with building back up historic biodiversity speci fic to the park . The plan outlines specific recommended activities in order to protect the health of the forest as one living organism. N ew recreational opportunities and education are intended to engage broader publics.

Houston Wilderness is an alliance between environmental, business, and government interests to protect the biodiversity specific to the Houston region. [55] In addition to the LTRP, Houston Wilderness contributes to other projects, including the Texas Monarch Flyaway Strategy Program. The program fights to eliminate habitat destruction that threatens the annual migration of Monarch Butterflies and their pollination. [56] Originally created for the Gulf-Houston region, the need for greater coordination pushed the aim to be a contiguous monarch habitat along the texas coastline and in certain upland regions.

The Gulf-Houston Region al Conservation Plan has 4 key initiatives that, if fully funded and completed, will include 280,000 acres of land acquisition and 15,000 acres of land easements and restoration. [57] There are four projects identified. The Riparian Corridor Protection Initiative is designed to protect the landscape within watersheds that feed into Galveston Bay. The landscape includes r iparian forests and wetlands connected by a system of rivers, creeks, and bayous. The Prairie Conservation Initiative aims to r estore and preserve prairie remnants to re-establish a cohesive prairie in the region. The Galveston Bay Habitat Acquisition and Easements Initiative aims to restore habitats in the areas around Galveston Bay, including coastal wetlands, barrier islands, and estuaries. The final initiative is the Galveston Bay Oyster Reefs & Migratory Bird Habitat Initiative , which preserves, restores, and creates Galveston Bay oyster reefs, inland rookery islands and other bird habitat.

Houston Audubon is a land trust organization that engages in regional conservation, education and advocacy that focuses on protecting the natural environment for birds and people. [58] Owning and managing bird sanctuaries is the organization's main strategy to protect bird habitat. Their reserves are distributed throughout the Greater Houston area. The organization currently owns 3,362 acres spread out over 17 sanctuaries in five countries. [59] One of their conservation initiatives focusing on urban ecosystems is their Bird-Friendly Communities Initiative. To safeguard the ecological value of birds, including pest management and seed dispersal, and increase bird watching opportunities, the Houston Audubon provides resources to add bird-friendly habitats to yards, parks, and other types of green space. [60]

Attwater’s Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge , currently located in the peri-urban zone of Houston, was established to protect tallgrass prairie. [61]

Public Awareness

Flooding from 2018’s Hurricane Harvey has raised awareness about environmental concerns and planning in the Houston area. There are also many citizen’s groups dedicated to environmental issues, including those who run parks and conservancies across the region. However, much of the concern towards the environment has gone directly toward flood mitigation and not biodiversity specifically. In addition, the culture of Houston as a place of boundless economic growth and development reduces support for environmental regulation and land conservation. Houston has been built on expansion, oil, and shipping, and to acknowledge the danger of climate change shows the inherent risk of these industries integral to Houston’s history and pride. This makes it harder to gain support for biodiversity projects, although it is growing considerably.

[1] Texas Almanac, “Harris County,” https://texasalmanac.com/topics/government/harris-county (accessed July 9, 2018)

[2] CEPF. “North American Coastal Plain.” Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/north-american-coastal-plain.

[3] CEPF. “North American Coastal Plain - Species.” Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/north-american-coastal-plain/species .

[4] CEPF. “North American Coastal Plain - Species.” Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/north-american-coastal-plain/species .

[5] CEPF. “North American Coastal Plain - Threats.” Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/north-american-coastal-plain/threats.

[6] WWF. “Southern North America: Southern United States into Northern Mexico | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0701.

[7] WWF. “Southern North America: Southern United States into Northern Mexico | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0701.

[8] WWF. “Southern North America: Southern United States into Northern Mexico | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0701.

[9] WWF. “Southern North America: Southern United States into Northern Mexico | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0701.

[10] “Western Gulf Coastal Grasslands.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed May 30, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/50701.

[11] WWF. “Piney Woods Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0523.

[12] WWF. “Piney Woods Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0523.

[13] “Piney Woods Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/50523.

[14] Texas State Historical Association, “Houston, TX,” https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hdh03 (accessed July 9, 2018)

[15] Texas State Historical Association, “Spindletop Oilfield,” https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/dos03 (accessed July 9, 2018)

[16] Houston History Magazine, “Joseph Jay Pastoria and the Single Tax in Houston, 1911-1917,” https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/dos03 (accessed July 9, 2018)

[17] ibid.

[18] Texas Community Watershed Partners, “Houston-Area Freshwater Wetland Loss, 1992-2010,” http://tcwp.tamu.edu/files/2015/06/WetlandLossPub.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018)

[19] The New York Times, “,” https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/30/us/houston-flooding-growth-regulation.html (accessed July 9, 2018)

[20] WWF, “Southern North America: Southern United States into northern Mexico,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0701 (accessed July 11, 2018)

[21] National Wetlands Research Center, “The Coastal Prairie Region,” https://www.nwrc.usgs.gov/prairie/tcpr.htm (accessed July 11, 2018)

[22] ibid.

[23] Needs citation

[24] Chron, “See where Superfund Sites are in the Greater Houston area,” https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/See-where-Superfund-sites-are-in-the-Greater-12177396.php#photo-7170697 (accessed July 11, 2018)

[25] The New York Times, “A Sea of Health and Environmental Hazards in Houston’s Floodwaters,” https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/31/us/houston-contaminated-floodwaters.html (accessed July 11, 2018)

[26] Texas Tribune, “On the Records: Mapping U.S. Population Growth by County,” https://www.texastribune.org/2011/03/25/maps-visualize-us-population-growth-by-county/ (accessed July 11, 2018)

[27] Houston-Galveston Area Council, “Current Maps and Table,” http://www.h-gac.com/community/socioeconomic/documents/Current_Maps_and_Tables.pdf (accessed July 11, 2018)

[28] Culture Map Houston, “Back to the City,” http://houston.culturemap.com/news/entertainment/06-30-10-back-to-the-city-has-suburban-sprawl-lost-its-sizzle/ (accessed July 11, 2018)

[29] Pearson, “Local Government in Texas,” https://web.archive.org/web/20090506115644/http://wps.prenhall.com/hss_dye_politics_6/27/7116/1821883.cw/index.html (accessed July 11, 2018)

[30] City of Houston, “Super Neighborhoods,” http://www.houstontx.gov/superneighborhoods/ (accessed July 11, 2018)

[31] Houston-Galveston Area Council, “What is H-GAC,” http://www.h-gac.com/about/default.aspx (accessed July 11, 2018)

[32] Harris County Flood Control District, “About the District,” https://www.hcfcd.org/about/ (accessed July 13, 2018)

[33] Harris County Flood Control District, “Tree Planting Program,” https://www.hcfcd.org/our-programs/tree-planting-program/ (accessed July 13, 2018); Harris County Flood Control District, “Vegetation Management,” https://www.hcfcd.org/our-programs/vegetation-management/ (accessed July 13, 2018)

[34] Plan Houston, “Plan Houston,” http://planhouston.org/sites/default/files/plans/Final_Plan_Houston.pdf (accessed July 13, 2018)

[35] Harris County Engineering Department, “U.S. 290 Area Major Thoroughfare Study,” http://www.eng.hctx.net/US290-Area (accessed July 13, 2018)

[36] Harris County Engineering Department, “2016 MAJOR THOROUGHFARE AND FREEWAY PLAN AMENDMENTS (MTFPA),” http://www.eng.hctx.net/Portals/33/Publications/US290/E.pdf (accessed July 13, 2018)

[37] Edwin Buitelaar, “Zoning, More Than Just a Tool: Explaining Houston's Regulatory Practice,” European Planning Studies 17, no. 7 (2009): 1049-1069

[38] ibid.

[39] Kinder Institute for Urban Research, “Forget What You’ve Heard, Houston Really Does Have Zoning (Sort Of),” https://kinder.rice.edu/2015/09/08/forget-what-youve-heard-houston-really-does-have-zoning-sort-of/#.WUFLK-vyuUl (accessed July 12, 2018)

[40] City of Houston, “Land Regulation and Development,” http://www.houstontx.gov/planning/Publications/inform_brch/landreg_dev_broch_jan2012.pdf (accessed July 13, 2018)

[41] City of Houston, “City of Houston, Texas, Ordinance No. 2015-639,” http://www.houstontx.gov/planning/DevelopRegs/docs_pdfs/Ord_2015-639.pdf (accessed July 13, 2018)

[42] CITES, “List of Parties to the Convention,” https://www.cites.org/eng/disc/parties/index.php (accessed July 13, 2018); Ramsar, “Country Profiles,” https://www.ramsar.org/country-profiles (accessed July 13, 2018)

[43] US Fish and Wildlife Service, “Endangered Species Act,” https://www.fws.gov/endangered/laws-policies/ (accessed July 13, 2018)

[44] Gulf Houston Regional Conservation Plan, “About Us,” http://www.gulfhoustonrcp.org/ (accessed July 17, 2018)

[45] Gulf Houston Regional Conservation Plan, “Executive Summary & 24% By 2040 Action Agenda,” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/561ac8e7e4b05a82a1711b03/t/5afef2311ae6cf326e272f7f/1526657587060/Gulf-Houston+RCP+-+Executive+Summary.pdf (accessed July 17, 2018)

[46] Houston Wilderness, “Sam Houston Greenbelt Network,” http://houstonwilderness.org/greenbelt-network/ (accessed July 18, 2018)

[47] City of Houston, “About HPARD,” http://houstontx.gov/parks/aboutus.html (accessed July 16, 2018)

[48] City of Houston, “GREENSPACE MANAGEMENT DIVISION,” http://houstontx.gov/parks/greenspace.html (accessed July 16, 2018)

[49] City of Houston, “NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PROGRAM,” http://www.houstontx.gov/parks/naturalresources.html (accessed July 18, 2018)

[50] Katy Prairie Conservancy, “Mission and Goals,” http://www.katyprairie.org/mission-goals/ (accessed July 17, 2018)

[51] Buffalo Bayou Partnership, “Yolanda Black Navarro Buffalo Bend Nature Park,”

[52] City of Houston, “Houston Parks and Recreation Department,” http://www.houstontx.gov/parks/index.html, (accessed July 17, 2018)

[53] City of Houston, “NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PROGRAM,” http://www.houstontx.gov/parks/naturalresources.html (accessed July 18, 2018)

[54] City of Houston. “Lake Houston Wilderness Park - Forest and Wildlife Management Plan,” http://www.houstontx.gov/parks/pdfs/2008/Forest&WildlifeManagementPlanLakeHoustonWildernessPark.pdf (accessed July 16, 2018)

[55] Citizens’ Environmental Council Houston, “Houston Wilderness,” http://www.cechouston.org/resource-guide/environmental-directory/organization/Houston+Wilderness/ (accessed July 18, 2019)

[56] Houston Wilderness, “The Texas Monarch Flyway Strategy Program,” http://houstonwilderness.org/mfs/ (accessed July 18, 2018)

[57] Gulf Houston Regional Conservation Plan, “Key Initiatives,” http://www.gulfhoustonrcp.org/#initiatives (accessed July 18, 2018)

[58] Houston Audubon, “About Us,” https://houstonaudubon.org/about/ (accessed July 18, 2018)

[59] Houston Audubon, “Land Conservation,” https://houstonaudubon.org/conservation/land-conservation.html (accessed July 18, 2018)

[60] Bird Friendly Houston, “Why Birds Matter and the Houston Connection,” http://www.birdfriendlyhouston.org/get-started/the-houston-connection/ (accessed July 18, 2018)

[61] WWF. “Southern North America: Southern United States into Northern Mexico | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed May 30, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0701.