Perth, Australia

- Global Location plan: 31.95oS, 115.86oE [1]

- Hotspot: Southwest Australia

- Population 2016: 1,861,000

- Projected population 2030: 2,329,000

- Mascot Species: numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus), western swamp turtle (Pseudemydura umbrina), red-capped parrot (Purpureicephalus spurius)

- Primary Crops: Wheat

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Crinia georgiana

- Crinia glauerti

- Limnodynastes dorsalis

- Geocrinia leai

- Heleioporus barycragus

- Metacrinia nichollsi

- Neobatrachus pelobatoides

- Litoria platycephala

- Heleioporus psammophilus

- Litoria adelaidensis

- Litoria moorei

- Crinia insignifera

- Crinia pseudinsignifera

- Heleioporus inornatus

- Myobatrachus gouldii

- Neobatrachus kunapalari

- Pseudophryne guentheri

- Pseudophryne occidentalis

- Neobatrachus albipes

- Heleioporus eyrei

- Heleioporus albopunctatus

Mammals

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Mesoplodon grayi

- Mesoplodon hectori

- Mesoplodon layardii

- Petrogale lateralis

- Phascogale calura

- Falsistrellus mackenziei

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Rattus fuscipes

- Sminthopsis gilberti

- Macropus eugenii

- Notomys mitchellii

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Mormopterus kitcheneri

- Tursiops truncatus

- Petrogale lateralis

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Chalinolobus morio

- Lagenorhynchus obscurus

- Mus musculus

- Austronomus australis

- Grampus griseus

- Hydromys chrysogaster

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Macropus robustus

- Sminthopsis fuliginosus

- Sminthopsis granulipes

- Pseudocheirus occidentalis

- Orcinus orca

- Phascogale tapoatafa

- Hyperoodon planifrons

- Macropus irma

- Berardius arnuxii

- Arctocephalus forsteri

- Isoodon obesulus

- Sminthopsis crassicaudata

- Trichosurus vulpecula

- Tachyglossus aculeatus

- Mesoplodon mirus

- Delphinus delphis

- Setonix brachyurus

- Vespadelus baverstocki

- Sminthopsis dolichura

- Macrotis lagotis

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Tarsipes rostratus

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Vulpes vulpes

- Eubalaena australis

- Lissodelphis peronii

- Pseudomys albocinereus

- Setonix brachyurus

- Antechinus flavipes

- Sminthopsis griseoventer

- Nyctophilus geoffroyi

- Stenella attenuata

- Nyctophilus gouldi

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Kogia sima

- Mesoplodon bowdoini

- Scotorepens balstoni

- Macropus eugenii

- Caperea marginata

- Chalinolobus gouldii

- Dasyurus geoffroii

- Vespadelus regulus

- Myrmecobius fasciatus

- Myrmecobius fasciatus

- Neophoca cinerea

- Notomys alexis

- Macropus fuliginosus

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Balaenoptera physalus

- Bettongia penicillata

- Globicephala melas

- Kogia breviceps

- Cercartetus concinnus

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

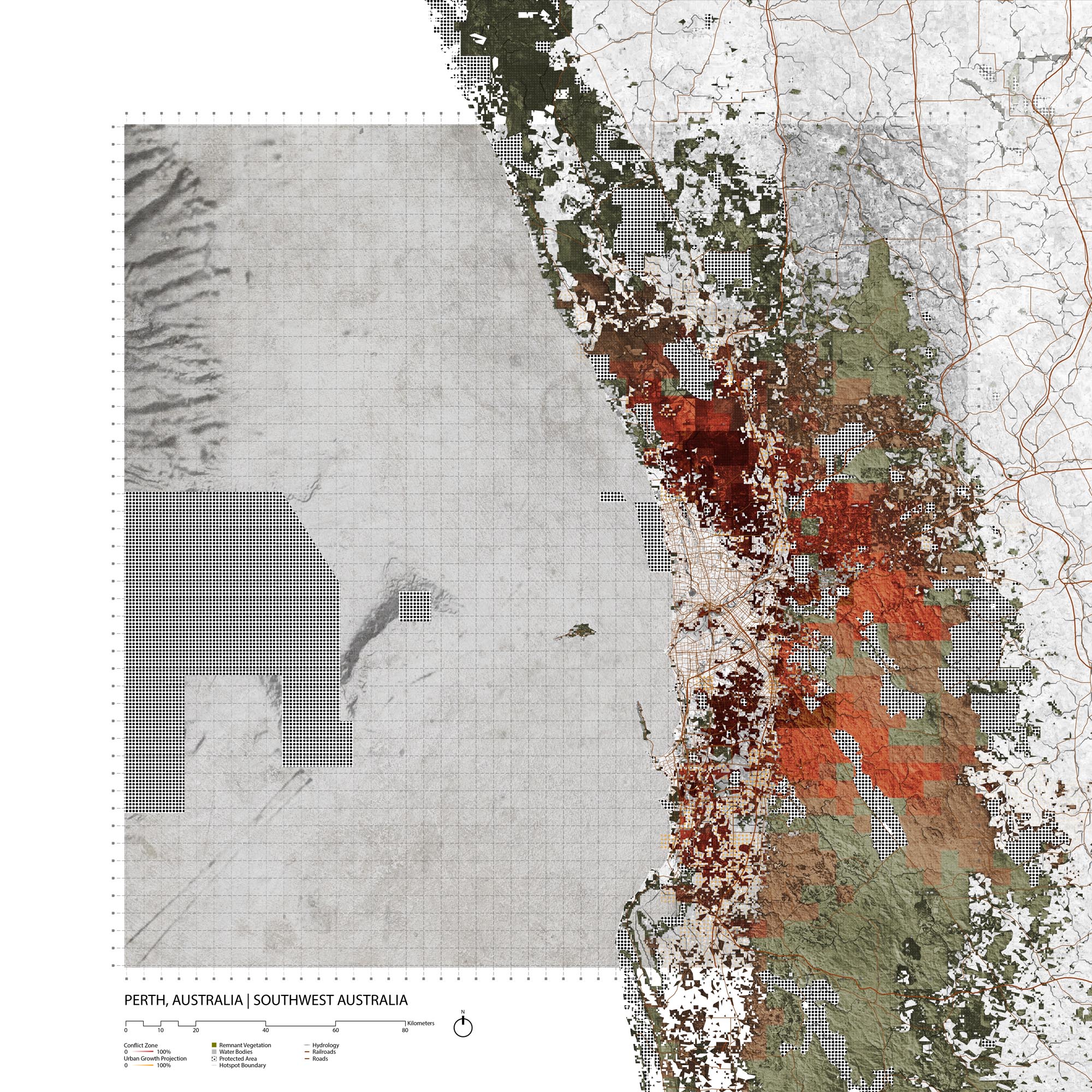

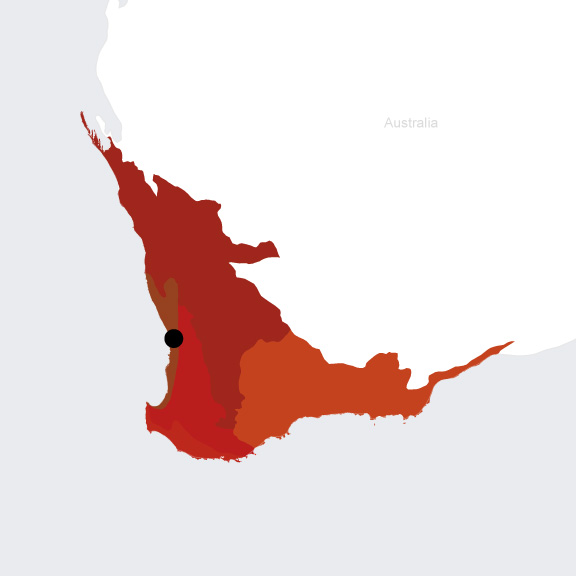

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Perth Metropolitan Area is primarily in the Swan Coastal Plain Scrub and Woodlands Ecoregion but has also started to grow into the Southwest Australia Woodlands Ecoregion. Both ecoregions are located in the Southwest Australia Hotspot.

At the national/continental level, Australia has had an extraordinarily high rate of land mammal extinctions over the last 200 years. More than 10% of its 273 endemic terrestrial mammals have disappeared, accounting for more than 50% of global mammal extinctions during this time period. The primary driver of these extinctions has likely been predation by introduced species (including feral cats and foxes) as well as altered fire regimes. [2] Many more birds and mammals are at high risk of extinction in the next two decades. Their primary threats continue to include predation by introduced species as well as habitat loss from land clearing and other development. [3]

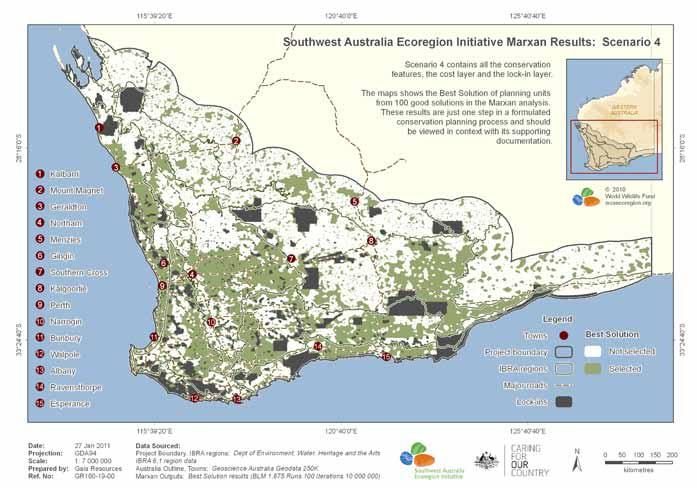

Southwest Australia Hotspot

Protected areas in Southwest Australia

The Southwest Australia Hotspot occupies around 356,700 km 2 of the southwestern tip of the Australian continent. Precipitation is comparatively high, with a seasonal cycle marked by dry summers and rainy winters. The dominant vegetation types are Eucalyptus woodlands and Mallee shrublands, and the ecosystems they underpin are characterized by plant and reptilian endemism. [4] The high rates of endemism in this hotspot have been attributed to isolation (vast deserts have separated this region from the rest of the continent for millions of years), and extreme environmental conditions including intense climate shifts and poor soils that had lead to adaptive specialization and speciation. [5]

Species statistics [6]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

5,570 |

>50% |

- jarrah ( Eucalyptus marginata ), marri ( E. calophylla ), and karri ( E. diversicolor ) |

|

Birds |

>280 |

12 |

- Endangered Carnaby's black-cockatoo ( Zanda latirostris ) |

|

Mammals |

~60 |

12 |

- Endangered [7] numbat ( Myrmecobius fasciatus ) |

|

Reptiles |

>175 |

~30 |

- highest levels of diversity of any country in the world

|

|

Amphibians |

>30 |

~66% |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

~20 |

~50% |

|

Presently, only 30 percent of Southwest Australia’s original vegetation remains intact. Main threats to the Hotspot’s biodiversity include agriculture, the alteration of fire regimes, mining, and the dieback caused by

Phytophora cinnamomi

, a plant pathogen that thrives in wetter regions and kills susceptible plants by attacking their root systems. It affects more than 40 percent of the native plant species and half of all endangered plant species in Western Australia, and is spread primarily through human activity moving infected soil.

[8]

Introduced alien species, particularly foxes and cats, have caused drastic declines in native mammal species.

[9]

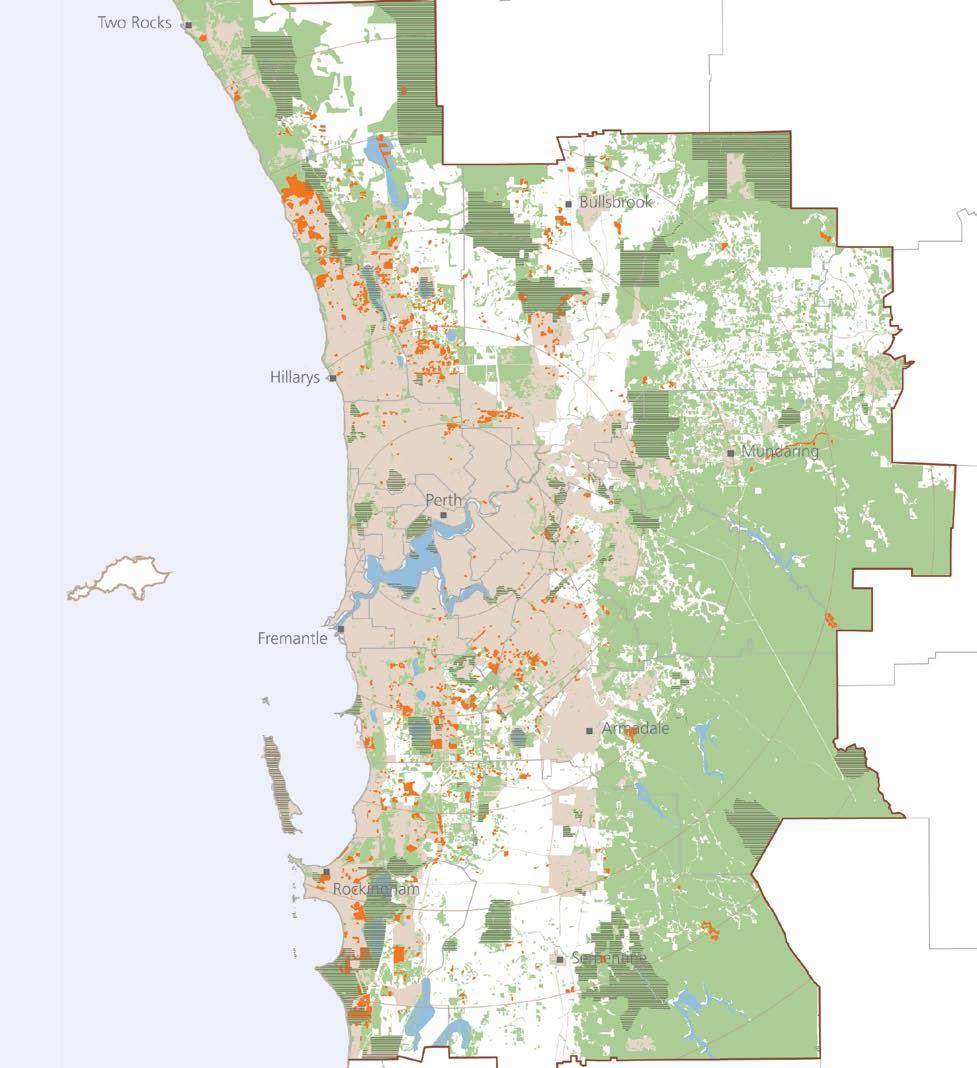

Swan Coastal Plain Scrub & Woodlands

This ecoregion runs along the Swan Coastal Plain, a low-lying belt 25 to 30 km wide that ends in the west at the Darling Scarp, which marks the transition from the Swan Coastal Plain up to the Precambrian Yilgarn Block. [10] This low lying coastal region is largely shaped by water. It includes large micro-tidal estuarine systems (such as the Swan-Canning Estuary), a number of lakes cut off from the sea by barrier dunes, and seasonal wetlands that provide the most diverse habitat on the Swan Coastal Plain. Rivers flowing west from the Darling Plateau run through this ecoregion. The varied geology and topography thus sustains a variety of ecosystems from coastal dunes with scrub-heath communities, sandplains, to Banksia and Eucalypt woodlands. [11]

The Swan Coastal Plain, like Western Australia more broadly, has great floral diversity (with 2000 angiosperm species). Endemism is highest at the species level, though there are also some genera that are wholly restricted to the southwestern region. About 15 percent of wildflowers in this region are pollinated by vertebrates like the western pygmy possum ( Cercartetus concinnus ) and the honey possum ( Tarsipes rostratus ). Noteworthy mammals found in this ecoregion include tammar wallabies ( Macropus eugenii ) and Vulnerable [12] quokkas ( Setonix brachyurus ). The Critically Endangered western swamp tortoise ( Pseudemydura umbrina ) —Australia’s rarest reptile— is restricted to the ephemeral swamps at the junction between the coastal plain and the Darling Scarp, nowhere outside of this ecoregion. [13]

As of 1995, nearly 80 percent of the Swan Coastal Plain had already been cleared. The primary ongoing threats to remaining habitats are urban expansion and human use. Dieback disease among the iconic Proteaceae species and more frequent fire regimes are also significant threats. [14] According to the Digital Observatory for Protected Areas, 13 percent of the Swan Coastal Plain Scrub and Woodlands ecoregion is protected, and 6.28 percent is considered connected. [15] The Australian government has tried to afford special protections to a number of Swan Coastal Plain woodlands communities by listing them as Threatened Ecological Communities under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. Yet only about 79 hectares of these communities remain, of which only 5 hectares are not vested for use. [16]

Southwest Australia Woodlands

The Southwest Australia Woodlands ecoregion is primarily located atop the inland plateau of the Yilgarn Block and its margins, which ranges from 280m to 340m in elevation. It also includes the Darling Scarp and Plateau in the east (ranging from 300 to 400 m), and the low lying Blackwood Plateau in the south (100 to 150 m). The ecoregion receives relatively high precipitation (from 635 to 1,300 mm per year, higher toward the coast). The summer drought is distinct. The ecoregion is mostly dominated by two types of Eucalyptus forest characterized respectively by jarrah ( Eucalyptus marginata ) and marri ( Eucalyptus calophylla ). The extensive wheatbelt of Western Australia runs along the inland eastern border of the ecoregion. Vegetation here is comprised of open Eucalypt woodlands containing wheatbelt wandoo ( Eucalyptus capillosa ) and powderbark ( Eucalyptus accedens ). [17]

Overall, species richness in this ecoregion decreases as one moves inland and high species diversity is often concentrated in prominent upland areas. Since Western Australia contains some of the oldest rocks in the world, the ecoregion is characterized by weathered, low-nutrient soils. The mosaic of soil types is made legible in the high diversity among plants in the region. In terms of animal species, a number of endangered or restricted-range mammals are found, including the numbat ( Myrmecobius fasciatus ), chuditch ( Dasyurus geoffroii ), tammar wallaby ( Macropus eugenii ), and ringtail possum ( Dasyurus geoffroii ). The endemism rate of frogs is especially high; only two out of 30 species in the are not endemic. [18]

As of 1999, 44 percent of all jarrah forests and close to 90 percent of all eucalyptus woodlands in this ecoregion were cleared for agriculture, logging, and mining. While there are a number of larger protected areas, 70 percent of national parks and nature reserves are smaller than 1 square-kilometer in area. Other major threats include introduced invasive plant species, heavy grazing, and severe dieback caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi . Rising water tables and salinization also cause concerns on agricultural lands. [19] Currently, the ecoregion is 13 percent protected but only 6.83 percent connected. [20]

Environmental History

Founded in 1829 the city of Perth was deve loped on the Swan River by British colonial forces with a view to it becoming a colonial agricultural hub. In direct conflict with indigenous peoples who had subsisted in this landscape for over 40,0000 years the city is characterized by the imposition of an English landscape sensibility on an arid estuarine and coastal ecology. For much of the 19th century the city drew its wealth from exports of primary resources (lumber, wool and wheat) to England; then the city grew rapidly in the 20 th century in the form of low density suburbia due to several economic booms related to mineral extraction from the regional landscapes of Western Australia.

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Perth is surrounded by ‘the wheat-belt’ a vast region of monocultures suffering from salinization due to extensive land clearance. The city is growing rapidly into largely degraded agricultural and pasture lands. Clearance of remnant coastal vegetation harboring high biodiversity is a noted consequence of suburban growth to the north. Though development has negative impacts on peri-urban biodiversity, the city has seen a growing awareness of its biodiverse context due to a strong local environmental movement coupled with international tourism related to the region’s unique flora and fauna. The city is endeavoring to increase its density, contain its urban sprawl and restore the ecological quality of its degraded agricultural landscapes.

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Perth is a low-density city even by Australian standards, with a strong cultural identity born of the “great Australian dream” of a single family detached house with a large backyard. It has grown in bursts during economic booms in the mining and resource development sectors, more than quadrupling in population size since World War II. The city’s form was greatly shaped by the growing popularity of the automobile and the contemporaneous period of rapid population growth in the 1950s and 60s. [21]

A mining boom that started in the early 2000s lead to very rapid population growth, including from overseas immigration. Its growth in that decade was concentrated in the out suburbs, with those suburbs with greenfield land available showing some of the strongest growth trends. The growth is strongest in extending further north and south along the coast, rather than moving inland. [22] According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the annual rate of growth of the population of the Greater Perth Area ranged from .9% and 1.5% between 2013 and 2018. [23]

Governance

Australia is a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy with a second tier of government that encopasses six states and two inland territories. Perth is the capital of the state of Western Australia. States are further divided in to local government areas, that are recognized by the constitutions of each of the states but not by the national constitution. These are generally called councils but names such as city, municipality, shire, and region are also given and have geographic interpretations.The Regional Development Commissions Act 1993 organized those the LGAs of Western Australia in to regions in order create commissions that would promote the economic development of those regions. The Perth Metropolitan Region was delineated in the Planning and Development Act 2005 . This metropolitan region includes 30 local government areas . Some planning documents developed by the Western Australian government have grouped the Perth Metropolitan Region with the Peel Region to the south in response to urbanization trends that are leading to the conurbation of the Perth metro area and the Swan Coastal Plain urban areas of the Peel region.

Governance Structure of Planning and Environment

National

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development [24]

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development has issued several plans and frameworks:

-2011 Our Cities, Our Future [25] —A National Urban Policy for a productive sustainable and liveable future

-2011 Creating Places for People--an urban design protocol for Australian Cities [26]

- 2016 Australian Infrastructure Plan is a national plan for building out infrastructure to support compact urban development, though it was criticized for focusing

- 2016 Smart Cities Plan is a federal framework for city policies that replaces the 2011 Our Cities, Our Future Plan

Department of the Environment and Energy

Australia’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy 2010-2030 is the national biodiversity management and conservation framework. This document serves as the NBSAP for the CBD. The Australian Biological Resources Study is the national focal point for taxonomy, leading the effort to discover, name and classify Australia’s living organisms. [27] Under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act, the Department of the Environment and Energy must maintain a list of threatened species and ecological communities for; new or intensified land uses in areas identified as having threatened ecological communities must first be approved by the Australian Government Minister for the Environment. [28] Twenty four threatened communities that might occur in Western Australia have been identified. [29] In 2015, the first Australian federal minister for cities and the built environment was appointed. This was seen as a signal that after many years of neglect, the federal government was realizing the importance of developing policy for its rapidly growing urban areas. [30]

State Level: Western Australia

Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage

The Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage is “responsible for state level land use planning and management and oversight of Aboriginal cultural heritage and built heritage matters” [31] Western Australian Planning Commission (WAPC) is the planning department’s statutory authority with responsibility for state-wide “urban, rural and regional integrated strategic and statutory land use planning and land development”. Its authority was established under the Planning and Development Act 2005 . The WAPC implements the State Planning Strategy. [32] Plans:

-State Planning Strategy 2050

-2010: Directions 2031 and Beyond

-2018: Draft Perth and Peel @ 3.5 million (aka Green Growth Plan will supplant Directions 2031 if it gets approved; has been stalled since 2011) An interactive map of the draft plan is available to the public. [33]

Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions

Created in 2017, this department brought together the Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority, Rottnest Island Authority, Zoological Parks Authority and the former Department of Parks and Wildlife. [34] This department manages Western Australia’s parks, advocates for wildlife conservation, provides scientific evidence for effective conservation of WA’s biodiversity. [35]

City Policy/Planning

In their article in the journal of Leadership and Management and Engineering , Hiller et al find that city planning in Australia has a high degree of interconnectedness across national, state, and local plans. [36] Within this hierarchy, however, s tates have especially broad powers when it comes to metropolitan planning and infrastructure provision, and capital cities are very dominant in their states in terms of population aggregation and power. [37] In their article looking at the evolving discourse of planning in Perth between 1955 and 2010, McCallum et al. find that “there is a characteristic “Australian paradigm” of strategic spatial planning, distinguished by its long-range plans, considerable land use detail, reliance on private investment and role as a coordinating instrument for development and infrastructure”. [38]

Development Plan

There were five spatial development plans produced for Perth between 1955 and 2018, all during times of significant economic and population growth. [39]

-1955: Plan for the Metropolitan Region : Perth’s first strategic plan was prepared by British planner/architect Gordon Stephenson and the Perth Town Planning Commissioner, Alistair Hepburn

-1963: Metropolitan Region Scheme : Based on the Stephenson-Hepburn, the MRS became the first statutory instrument that set out zoning and released land for development. The Metropolitan Region Planning Authority was established as the body that would have legislative authority over the MRS.

- 1970: Corridor Plan for Perth : This plan produced by the Town Planning Department was a response to the car-centric booming growth of the city. Its suggestions for concentrating growth by directing it along 4 corridors was highly controversial and it stagnated in the review process until the 1980s. When it was finally revisited, revised in favor of more compact development, and elaborated through the development of structural plans for three of the original corridors and one alternative corridor that moved development away from a rural and water catchment area, the plan was met with significant community opposition. Larger political trends also contributed to the breakdown of bipartisan support for the plan, and for a period of time, for planning controls and processes more broadly.

-1990: Metroplan : Prepared by the Department of Planning and Urban Development , this plan nominally embraced compact development but extended the planned area for urban expansion by 30%, and focused most of its attention on developing a hierarchy of commercial centres.

-2010: Directions 2031 and Beyond : This plan builds on the 2005 Network City: Community Planning Strategy for Perth and Peel plan which was developed by the Western Australian Planning Commission along with extensive community participation, but was not fully endorsed by the Western Australian government until it was revised in 2009. Whereas Network City proposed an urban growth boundary, a target of 60% infill for new housing, and a proposed development pattern that would integrate land use with transport, Directions 2031 reduced the target infill to 47% and focused on concentrating growth at activity centers connected by transport but not linking growth to transport. Directions 2031 generally curbed the ambitions and edge of the Network City plan.

-2018: Perth and Peel @ 3.5 : This plan prepared by the Western Australian Planning Commission anticipates that the Perth and Peel metro region will grow from a population of 2 million to a population of 3.5 by 2050.

Zoning

Zoning in Western Australia is regulated at two scales: state and local. Regional planning schemes are developed by the Government of Western Australia’s Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage. Regional schemes serve as a statutory mechanism intended to “assist strategic planning, the coordination of major infrastructure and sets aside areas for regional open space and other community purposes.” They set out broad land use zones and policy areas and identify land required for regional purposes. Two region schemes overlap with the greater Perth metro area: the Metropolitan Region Scheme and the Peel Region Scheme. [40]

District town planning schemes provide more detailed plans that are consistent with regional planning schemes.

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Australia’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy 2010-2030 (NBSAP V2) is the result of a review of Australia’s 1996 National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia’s Biodiversity (NBSAP V1). [41] In 2006, the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council (NRMMC) established the National Biodiversity Strategy Review Task Group to review the 1996 strategy and other state, territory, and local strategies for biodiversity conservation. This strategy identifies three levels of biodiversity: genetic diversity, species diversity, and ecosystem diversity. Australia’s biodiversity is presented as something to appreciate both in its own right and for its contribution to human existence. Within the plan, there is a set of priorities for action to help achieve a diverse and resilient Australia. The first priority is to engage all Australians in biodiversity conservation, by mainstreaming, increasing Indigenous engagement, and enhancing strategic investments and partnerships. The second is building ecosystem resilience in a changing climate, to be achieved by protecting diversity, maintaining and re-establishing ecosystem functions, and reducing threats. The third priority is to get measurable results, through improving and sharing knowledge, delivering conservation initiatives efficiently, and implementing robust national monitoring, reporting, and evaluation. Australia established a national long-term monitoring and reporting system, the Natural Resource Management Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting and Improvement Framework (MERI). The plan also sets specific targets for increasing ecological health for both the ecosystem and human society. Collaboration across different levels of organization is highly valued, with market incentives mentioned as an essential tactic. Protection of biodiversity is considered a responsibility for all Australians. Although the plan identifies habitat loss as a significant threat to biodiversity, it does not explicitly mention urbanization as a threat. In 2015, NRMMC would have assessed the progress and suitability of the targets and determined subsequent schemes. [42]

National

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) delineates the Australian Government’s responsibilities for biodiversity conservation. It defines a legal framework to “protect and manage nationally and internationally important flora, fauna, ecological communities and heritage places,” including restricting development on World Heritage Sites, Ramsar wetlands, threatened species communities, water resources, and others. [43]

State

At the state level, the Metropolitan Regional Scheme developed and administered by the WAPC designates Bush Forever Areas, as mandated by State Planning Policy 2.8: Bushland Policy for the Perth Metropolitan Region (prepared under the Planning and Development Act 2005 ). Bushland Forever is the core ecosystem protection policy in place in Western Australia; it provides a comprehensive policy for the protection of the 26 unique vegetation types found around Perth. The plan was to be fully implemented by 2010, but despite initial progress and rapid early achievements, the Bush Forever Office was dissolved into the Department of Planning and lost most of its staff and resources in the transition. Although WAPC has acquired many of the originally delineated Bush Forever sites, they have not been transferred to the Crown, sites have not been allocated to a suitable land manager, and management to established sites as conservation reserves has not been implemented. As of 2016, of the original 495 sites that were identified, only 80 Bush Forever Areas (or parts of them) were owned by WAPC, and 122 were managed, at least in part, by Local Government. Although many of the sites have been. While many of them have been delineated, they have not been rezoned in the MRS. The Urban Bushland Council WA that in order to effectively implement the policy, it is necessary to “revest sites and allocate conservation land managers to each Bush Forever Area; for Local Government Authorities to update and complete their Local Biodiversity Strategies and Local Plans; and to identify, protect and restore ecological linkages and Greenways as local developments continue.” [44]

The Local Biodiversity Program operated from 2001 to 2014, when it’s funding ran out. In that time, LBP provided local governments with “expert and technical advice, data and mapping to inform biodiversity planning and management, decision support tools and direct financial assistance.” Since LBP was dissolved, WALGA has continued to provide some of these services for a fee to local governments, and maintains all of the resources developed by LBP as publicly accessible online. [45]

Regional

The Natural Resource Management (NRM) model is an integrated system of management of land, water, soil, plans and animals, and is collectively administered by 56 Natural Resource Management (NRM) regional organizations that include both government agencies and NGOs working on addressing natural resource issues at the landscape and regional scales. The scope of these NRMs together encompasses the management of the entire continent. Although they all have different histories and constitutions, they have all been recognized by the Federal Government as part of the National Landcare Programme (the most recent successor to the original Natural Heritage Trust program). This national program is primarily a funding stream established by the Australian Government to support NRMs. The Perth metropolitan area mostly falls within the Perth NRM, but some of its suburbs/ conurbating cities fall under the purview of the Peel Harvey Catchment Council and the Wheatbelt NRM Council.

Local

Swan Region Strategy for Natural Resource Management is an integrated planning framework prepared by the Perth NRM.

The now defunct Southwest Australia Ecoregion Initiative was run by a consortium of organizations invested in long-term planning for biodiversity conservation in the Southwest Australia Hotspot. The initiative was formalised in 2002 when a Stakeholder Reference Group was formed; the SRG has was jointly chaired by the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) and WWF-Australia, and included representatives from NRM regional groups, Australian and State government agencies, and research and advocacy institutions and community groups. The group published a two part, spatialized plan for conservation in the Southwest Australia Hotspot that broke out its recommendations and assessments for decision-makers in one volume and for conservation planning practitioners in another. The report identified and explained the group’s methodology in developing systematic conservation, identifying areas with the highest representation of biodiversity as priority areas for systematic conservation. The report recommended 6 organizing actions for furthering systematic conservation in the hotspot: [46]

At the local government area level, the City of Joondalup, one of Perth’s northern suburb municipalities, was a participant in the ICLEI LAB Pioneer Programme and a signatory to the Durban Commitment. As part of its engagement with LAB, the City prepared a Biodiversity Report in 2008, followed by a Biodiversity Plan in 2009. [47]

The City of Fremantle participated in the One Planet Challenge and developed a “One Planet Strategy” intended to chart the path toward reducing the environmental footprint of Freemantle’s residents such that if everyone on the planet lived the way that the city’s residents would, then they would stay within the planet’s “carrying capacity.” Although the city sets target for increasing levels of biodiversity and space for wildlife, these are largely symbolic and not spatialized. [48]

[2] Woinarski, John C. Z., Andrew A. Burbidge, and Peter L. Harrison. “Ongoing Unraveling of a Continental Fauna: Decline and Extinction of Australian Mammals since European Settlement.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, no. 15 (April 14, 2015): 4531–40. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1417301112 .

[3] “Australia’s Mammal Extinction Rate Could Worsen.” Phys.org, April 24, 2018. https://phys.org/news/2018-04-australia-mammal-extinction-worsen-scientists.html .

[4] CEPF. “Southwest Australia.” Accessed May 22, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/southwest-australia .

[5] CEPF. “Southwest Australia - Species.” Accessed May 22, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/southwest-australia/species .

[6] CEPF. “Southwest Australia - Species.” Accessed May 22, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/southwest-australia/species .

[7] “Numbat.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en .

[8] “Phytophthora Dieback.” Government of Western Australia: Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. Accessed June 4, 2019. https://www.dpaw.wa.gov.au/management/pests-diseases/phytophthora-dieback .

[9] CEPF. “Southwest Australia - Threats.” Accessed May 22, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/southwest-australia/threats .

[10] WWF. “Southwestern Coast of Australia | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed May 22, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/aa1205 .

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Quokka.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en .

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Swan Coastal Plain Scrub and Woodlands.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed June 4, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/11205 .

[16] Australian Government: Department of the Environment and Energy. “Shrublands and Woodlands of the Eastern Swan Coastal Plain.” Accessed May 22, 2019. http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/conservation-advices/ shrublands-woodlands-of-the-eastern-swan-coastal-plain

[17] WWF. “Southeastern Australia | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed May 22, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/aa1210 .

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Southwest Australia Woodlands.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed May 22, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/11210 .

[21] Maccallum, Diana, and Diane Hopkins. “The Changing Discourse of City Plans: Rationalities of Planning in Perth, 1955–2010.” Planning Theory & Practice 12, no. 4 (December 2011): 491. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2011.626313 .

[22] “Perth’s Population - a Story of Economic Boom.” . .Id the Population Experts (blog), May 29, 2012. https://blog.id.com.au/2012/population/population-trends/perths-population-a-story-of-economic-boom/ .

[23] “Greater Perth.” Australian Bureau of Statistics. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://itt.abs.gov.au/itt/r.jsp?RegionSummary®ion=5GPER&dataset=ABS_REGIONAL_ASGS2016&geoconcept=ASGS_2016&measure=MEASURE&datasetASGS=ABS_REGIONAL_ASGS2016&datasetLGA=ABS_REGIONAL_LGA2018®ionLGA=LGA_2018®ionASGS=ASGS_2016.

[24] Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities. “Cities.” Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://infrastructure.gov.au/cities/index.aspx .

[25] “Our Cities, Our Future — A National Urban Policy for a Productive, Sustainable and Liveable Future, 2011.” Australian Government | Infrastructure Australia, January 1, 2011. http://infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/policy-publications/publications/Our-Cities-Our-Future-2011.aspx .

[26] “Creating Places for People: An Urban Design Protocol for Australian Cities.” Australian Government | National Urban Policy Group, January 2011. https://urbandesign.org.au/content/uploads/2015/08/INFRA1219_MCU_R_SQUARE_URBAN_PROTOCOLS_1111_WEB_FA2.pdf .

[27] “Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS).” Department of the Environment and Energy. Accessed May 21, 2019. https://www.environment.gov.au/science/abrs .

[28] “About Threatened Ecological Communities.” Australian Department of the Environment and Energy. Accessed June 4, 2019. http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/communities/about#What_does_listing_a_threatened_ecological_community_achieve .

[29] “Map of EPBC-Listed Ecological Communities Occurring in Western Australia.” Commonwealth of Australia: Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN). Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, 2013. http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/7e5ca5ea-2c56-4dc3-9bb3-44e312cb37d6/files/wa-tec.pdf

[30] Dodson, Jago. “Urban Policy: Could the Federal Government Finally ‘Get’ Cities?” The Conversation, September 27, 2015. http://theconversation.com/urban-policy-could-the-federal-government-finally-get-cities-47858 .

[31] “What We Do - Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage.” Department of Planning Lands Heritage. Accessed May 21, 2019. https://www.dplh.wa.gov.au/about/the-department/what-we-do .

[32] “About the WAPC - Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage.” Department of Planning Lands Heritage. Accessed May 21, 2019. https://www.dplh.wa.gov.au/about/the-wapc/about-the-wapc.

[33] “Green Growth Plan.” Government of Western Australia: Interactive Draft Green Growth Plan. Accessed June 7, 2019. https://espatial.planning.wa.gov.au/mapviewer/Index.html?viewer=greengrowthplan .

[34] “About Us.” Government of Western Australia | Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.dbca.wa.gov.au/about .

[35] “Mission, Values and Vision.” Government of Western Australia | Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.dbca.wa.gov.au/about/25-our-values .

[36] Hiller, B. T., B. J. Melotte, and S. M. Hiller. “Uncontrolled Sprawl or Managed Growth? An Australian Case Study.” Leadership and Management in Engineering 13, no. 3 (July 2013): 144–70. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LM.1943-5630.0000238 .

[37] Maccallum, Diana, and Diane Hopkins. “The Changing Discourse of City Plans: Rationalities of Planning in Perth, 1955–2010.” Planning Theory & Practice 12, no. 4 (December 2011): 491. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2011.626313 .

[38] Maccallum, Diana, and Diane Hopkins. “The Changing Discourse of City Plans: Rationalities of Planning in Perth, 1955–2010.” Planning Theory & Practice 12, no. 4 (December 2011): 491. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2011.626313 .

[39] Maccallum, Diana, and Diane Hopkins. “The Changing Discourse of City Plans: Rationalities of Planning in Perth, 1955–2010.” Planning Theory & Practice 12, no. 4 (December 2011): 491. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2011.626313 .

[40] “Region Planning Schemes.” Government of Western Australia | Department of Planning Lands Heritage. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.dplh.wa.gov.au/information-and-services/district-and-regional-planning/region-planning-schemes .

[41] Convention on Biological Diversity, “CBD Strategy and Action Plan - Australia,” https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/au/au-nbsap-v2-en.pdf (accessed July 6, 2018)

[42] Convention on Biological Diversity, “CBD Strategy and Action Plan - Australia,” https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/au/au-nbsap-v2-en.pdf (accessed July 6, 2018)

[43] “Department of the Environment and Energy.” Department of the Environment and Energy. http://www.environment.gov.au/ . Accessed May 21, 2019.

[44] “Implementation of Bush Forever.” Urban Bushland Council WA. Accessed June 7, 2019. https://www.bushlandperth.org.au/implementation-bush-forever/ .

[45] “Celebrating 13 Years of Action for Biodiversity.” Western Australia Local Government Association, 2014.

[46] Witham, Danielle. “A Strategic Framework for Biodiversity Conservation; Report B: For Practioners of Conservation Planning.” Southwest Australia Ecoregion Initiative, 2012. https://www.gaiaresources.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/SWAE_Report_B_FINAL_SMALL.pdf . pp 3.

[47] “UBHub.” Accessed June 7, 2019. http://www.ubhub.org/map .

[48] “One Planet Fremantle Strategy.” City of Fremantle, 2014.

[49] “A Strategic Framework for Biodiversity Conservation; Report B: For Practioners of Conservation Planning.” Southwest Australia Ecoregion Initiative, 2012. https://www.gaiaresources.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/SWAE_Report_B_FINAL_SMALL.pdf . pp 76.