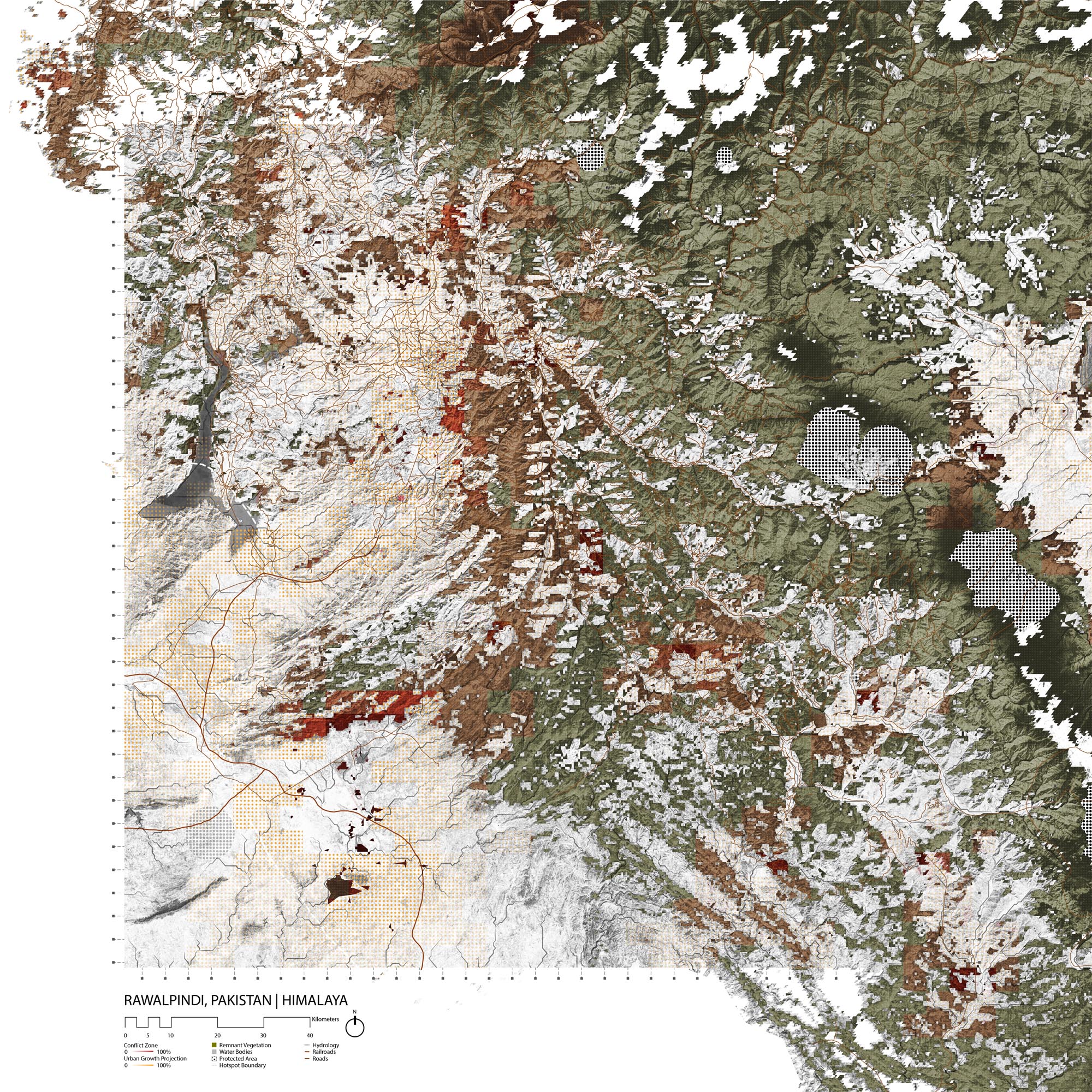

Rawalpindi, Pakistan

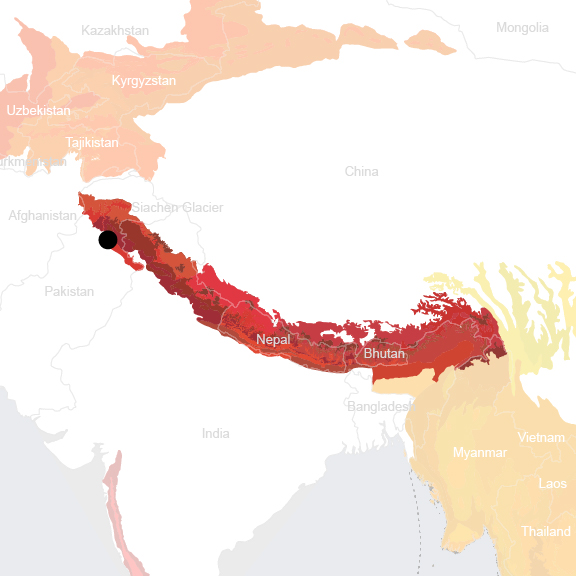

- Global Location plan: 33.60oN, 73.04oE[1]

- Hotspot: Himalaya. Western Himalayan Subalpine Conifer Forests[2]

- Population 2015: 2,506,000

- Projected population 2030: 3,806,000

- Mascot: Snow Leopard

- Crops: wheat, barley, corn and millet[3]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Microhyla ornata

- Uperodon systoma

- Fejervarya limnocharis

- Hoplobatrachus tigerinus

- Duttaphrynus melanostictus

- Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis

- Allopaa hazarensis

- Duttaphrynus himalayanus

- Bufotes latastii

- Bufotes pseudoraddei

- Duttaphrynus stomaticus

- Scutiger nyingchiensis

- Nanorana vicina

- Sphaerotheca breviceps

Mammals

- Meriones crassus

- Meriones libycus

- Meriones persicus

- Tadarida teniotis

- Barbastella leucomelas

- Myotis schaubi

- Otocolobus manul

- Ovis orientalis

- Rhinolophus blasii

- Rhinolophus ferrumequinum

- Rhinolophus euryale

- Rhombomys opimus

- Ursus arctos

- Ochotona rufescens

- Mellivora capensis

- Ursus arctos

- Ursus arctos

- Rhinolophus mehelyi

- Tatera indica

- Felis silvestris

- Plecotus macrobullaris

- Myotis emarginatus

- Allactaga williamsi

- Sus scrofa

- Pipistrellus aladdin

- Panthera pardus

- Panthera pardus

- Asellia tridens

- Rattus rattus

- Eptesicus bottae

- Panthera pardus

- Rhinopoma muscatellum

- Allactaga toussi

- Gerbillus aquilus

- Mus musculus

- Caracal caracal

- Felis chaus

- Gazella bennettii

- Jaculus jaculus

- Otocolobus manul

- Pipistrellus kuhlii

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Sciurus anomalus

- Lutra lutra

- Lynx lynx

- Hypsugo savii

- Meles meles

- Myotis blythii

- Hystrix indica

- Allactaga elater

- Chionomys nivalis

- Vulpes vulpes

- Lepus capensis

- Vulpes rueppellii

- Vormela peregusna

- Rhinolophus hipposideros

- Hemiechinus auritus

- Otocolobus manul

- Vespertilio murinus

- Vulpes cana

- Acinonyx jubatus

- Martes foina

- Apodemus flavicollis

- Arvicola amphibius

- Dryomys nitedula

- Ellobius lutescens

- Gazella subgutturosa

- Hyaena hyaena

- Myotis capaccinii

- Nesokia indica

- Ovis orientalis

- Ovis orientalis

- Capra aegagrus

- Microtus socialis

- Allactaga firouzi

- Canis lupus

- Cricetulus migratorius

- Calomyscus bailwardi

- Mustela nivalis

- Lepus tolai

- Pipistrellus pipistrellus

- Lynx lynx

- Paraechinus hypomelas

- Gerbillus nanus

- Eptesicus serotinus

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The city of Rawalpindi is located within the Himalaya hotspot and at the intersection of three different ecoregions – the Western Himalayan Subalpine Conifer Forests, the Himalayan Subtropical Pine Forests, and the Baluchistan Xeric Woodlands. All three ecoregions possess rich flora and fauna, but the diversity and endemism are relatively low in the first two. The ecoregion introduction will focus on the last one. [4]

The Himalaya is the youngest and highest mountain chain on Earth, and stretches in an arc across multiple national borders, including that of Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, India, and China. The hotspot features rugged, largely inaccessible mountainous landscapes, which make surveys difficult. Significant areas of forests are still little or entirely unexplored. Thus, its biodiversity is likely underestimated. Additionally, many unique and small cultures reside in the Himalayas. The northeast part of India in particular, contains more than 500 distinct ethnic groups. [5]

Species statistics [6]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~10,000 |

~3,160 |

- 71 endemic genera

|

|

Birds |

~980 |

15 |

|

|

Mammals |

~300 |

12 |

- Endangered South Asian river dolphin ( Platanista gangetica ), Endangered wild water buffalo ( Bubalus arnee ) |

|

Reptiles |

>175 |

~50 |

|

|

Amphibians |

105 |

>40 |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

~270 |

30 |

- three major drainage systems, the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra |

Despite its remoteness and inaccessibility, the Himalaya has not been spared from anthropogenic biodiversity loss. Greater link to the global market in recent decades has raised the demand for natural resources from the area, and steadily increasing population has led to extensive conversion of forests and grasslands. Cultivation of some crops such as barley, potato, and buckwheat reach into high elevations, and more lands are cleared in the summer months for livestock grazing. Logging (both legal and illegal) often occurs on extremely steep slopes, resulting in heavy erosion. Other threats include poaching, overexploitation for traditional medicine, poorly managed tourism, and political unrest. [7] A reappraisal in 2004 classified the Himalayan regions into two hotspots – the Indo-Burma and the newly distinguished Himalaya. CEPF’s 5 million US dollar investment from 2005 to 2010 concentrated on the Eastern Himalayas. [8]

Western Himalayan Subalpine Conifer Forests

This ecoregion covers Rawalpindi’s urban center and extends to the southeast. The Western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests represent the frontline of the forested regions in the western Himalayas, between 3,000 and 3,500 m, standing against the treeless alpine meadows to the north. Monsoons that sweep in from the Bay of Bengal contribute most of the rainfall, and thus create the east to west descending moisture gradient. Also, several birds and mammals exhibit seasonal migrations up and down the steep mountain slopes and depend on contiguous habitats for these movements. Although the region does not have a particularly rich biodiversity, it does harbor several focal large mammals of conservation importance. [9] One of those is the Critically Endangered [10] Himalayan brown bear ( Ursus arctos isabellinus ) [11] , a subspecies of the brown bear ( Ursus arctos ).

More than 70 percent of the original habitats have been cleared or degraded in the ecoregion. Slopes have been deforested for intensive cultivation, and the collection of highly prized yellow morel mushrooms ( Morchella esculenta ) coincides with several animals’ breeding seasons. In addition, collection of wood for both locals and tourists poses significant threats to the slow-regenerating forests. [12]

Currently, 9 percent of the ecoregion is protected in designations like sanctuaries and national parks, including one World Heritage site – the Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area. The protected areas possess a 3.02 percent connectivity. [13]

Himalayan Subtropical Pine Forests

The Himalayan subtropical pine forests are the largest in the Indo-Pacific region, extending from Pakistan in the west into Nepal and Bhutan. Some scientists believe that climate change and human disturbance have caused the lower-elevation oak forests to be degraded and invaded by the drought-resistant Chir pine ( Pinus roxburghii ), which is now the dominant species in the ecoregion. Because of frequent fires, the pine forests do not have a well-developed understory but support a rich growth of grasses. Compared with adjacent broadleaf forests, the ecoregion has relatively low species diversity and endemism levels. Some characteristic species include goral ( Naemorhedus goral ), barking deer ( Muntiacus muntjak ), and yellow-throated marten ( Martes flavigula ). [14]

Over half of the ecoregion’s original habitat has been destroyed or damaged. Agricultural construction such as terraced plots have almost eliminated all the natural forests in Nepal. Similar losses happen in neighboring countries, and the few larger remaining blocks are found in Bhutan. Other threats include overgrazing, overexploitation for fuelwood and fodder, road work, and quarrying. [15] Presently, only 5 percent of the ecoregion is protected, and connectivity lies at a low 1.31 percent. [16]

Balochistan Xeric Woodlands

West of the city of Rawalpindi, the climatic and slope variations give the Balochistan Xeric Woodlands many of the world’s biomes. The ecoregion spans from the Las Bela Valley and the high barren plateau of Balochistan from Southwest Pakistan to eastern Afghanistan. Extending to the north, it ends at the border of Eastern Hindu Kush and the Himalayan mountains. The area experiences low rainfall (annual average is less than 150 mm) and severe temperature fluctuations. Summers can reach over 40° C and winters are generally cold. Southwest monsoon season is from June to September. [17]

This ecoregion is known for its biodiversity’s richness rather than endemism. There are more than 300 types of birds, of which migratory species number three times higher than restricted-range ones. The Indus valley is particularly abundant in waterfowls. Notable wild cats include the common leopard ( Panthera pardus ), caracal (Caracal caracal ), jungle cat ( Felis chaus ), and leopard cat ( Prionailurus bengalensis ). [18] Some threatened species in the ecoregion are the Critically Endangered [19] Balochistan black bear ( Ursus thibetanus gedrosianus ) – a subspecies of the Asiatic black bear [20] – and the Vulnerable mugger ( Crocodylus palustris ). [21]

Intensive logging over hundreds of years in the area has caused significant loss of the woodlands. Many habitats have been cleared for cultivation, and the remaining forests exist in highly fragmented small patches. Threats to biodiversity include overgrazing, construction of dams and barrages, irrigation, mining, and political instability; these are all contributing factors to deforestation, desertification, and land salinization. [22] At present, 3 percent of the ecoregion is protected and has a 1.24 percent of connectivity. [23]

Environmental History

A leader of the Gakhar tribe named Rawalpindi in reference to the ancient village of Rawals, a group of yogis, that had occupied it until a 14th century Mongol invasion. The village grew into the city under the rule of Sikh conqueror Milka Singh Thehpuria and was annexed by the British in 1849. [24]

The Indian colony, which had been administered by the East India Company, was named British Raj and fell directly under the rule of the British crown in 1857, when Indian soldiers mutinied. The Indian National Congress was established in 1885 by members of the Indian Middle class to contest British policies, and went on to become the center of the revolution. The United Kingdom finally promised India its independence after it supported the British army during World War II. [25]

Tensions between muslims and hindus in the colony called for the creation of two separate countries, India and Pakistan. As members of both religion fled to their respective designated countries to avoid discrimination, one region fell in between and continues to cause conflict to this day: Kashmir. The region was initially allowed to decide which country to join, and a local leader chose to join India even though the region’s population is 60% muslim, sparking a series of wars between the two countries. [26]

Rawalpindi is only 50km away from the border of the contested Kashmir Region, and constitutes the gateway to the Kashmir trading route . At the time of independence, in 1947, the city of Rawalpindi was 44% muslim, 34% Hindu and 17% Sikh. In the city, the Hindu and Sikh majority was in favor of joining India, whereas most citizens outside the city were in favor of joining Pakistan. [27]

Islamabad was founded just north of Rawalpindi by authoritarian leader General Ayub Khan in the 1960s. The Punjabi leader moved the capital from coastal Karachi, where Punjabis were a minority, to the other end of the country, where his power would be less vulnerable to a coup. [28] Islamabad was created from scratch, and planned as a car-friendly city above the older, less structured Rawalpindi. Today, the city is not adapted to its people, most of which do not own a car and don’t have access to clean water.

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

The air in Rawalpindi and Islamabad is heavily polluted, with respectively 107µg/m3 and 66 µg/m3 of 2.5 micron particulate matter (PM2.5), which is well above the WHO recommended level of 10µg/m3. [29] Brick factories constitute a major cause of air pollution . The use of deficient filters in steel mills further contributes to high concentrations of PM2.5 in the area. [30]

Rawalpindi is also facing major solid waste management issues. 20% of waste in the area is not collected by the collection system, especially in poorer communities. This waste is disposed of in open drains and spaces, and on the street. As for the portion of waste that is managed, it is usually disposed of in landfills that are not engineered to reduce leakage or landfill gases. [31]

Water pollution due to poor waste water management also poses a serious health and environmental hazard in the area. Indeed, 68% of water sources in Islamabad and 62% in Rawalpindi are deemed unfit for drinking. Bacteria is the main contaminant in drinking water, but nitrates, which typically come from fertilizers or animal waste, have also been found in high levels in the cities’ water supply. [32]

In agriculture, the use of high-yield crops has helped increase food production, but has also reduced the genetic diversity of local crops and created a reliance on pesticides. Thus, pesticide consumption has nearly increased tenfold betw een 1980 and 2010, and has caused up to a 90% reduction in friendly predator species, compromising local ecosystems. [33]

Land degradation is also posing a major threat to biodiversity, and caused mainly by erosion due from water and wind, loss of soil fertility, waterlogging, salinization, overgrazing and deforestation. [34]

South of the Islamabad-Rawalpindi area, cultures cover the landscape almost completely, leaving little room for natural vegetation. The same can be said for the west, aside from the Kala Chitta Reserve, the Khairi Murat reserve, and a few forests, namely the the Dhungi Reserved Forest, the Adiala Reserve Forest, and a wooded area just northeast of the latter. North and East of the cities, the landscape is covered in protected areas and natural forest cover that seems very well connected. However, residential areas are found throughout these forests, even though their houses have been built within the woods rather than on completely cleared land. [35]

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Informal developments, or “katchi abadis,” are very present in both cities. Islamabad reportedly counts 24 settlements, housing nearly 85,000 people altogether. [36] Afghan refugees constitute a major portion of the informal settlements; they arrived as early as the 1980s, during the the Soviet war in Afghanistan. [37] Informal settlements also house many ethnic minorities, and their dwellers are exposed to higher environmental hazards, namely to floods. The unplanned nature of settlements, mainly poor waste management, contributes to water pollution, especially in Rawalpindi, which is downstream of Islamabad. Ten of the settlements in Rawalpindi are deemed legal by the government, which supplies water and electricity to their inhabitants. The remaining communities are not supported in such ways, since the government is trying to inhibit their development. [38]

Some blame the growth of informal settlements due to illegal immigrants, for the degradation of the natural areas surrounding Islamabad. [39]

The population of Rawalpindi has grown an average 4% yearly, and informal settlements more specifically have grown since a real estate boom in the early 2000s, that caused an increase in the price of housing. [40] Between 1998 and 2017, the twin cities grew from 1.9 million to 3.1 million citizens. [41]

West of the Urban center, settlements in the woodlands have been desnifying at a relatively slow pace. A more drastic chang ein the city is the sprawl of the urban core onto neighobring agricultural lands. While Islamabad has visibly been developping in a rigid, planned grid to the north, Rawalpindi has expanded in a less regular fashion, alongside roads or more drastically with vase developments like Bahria town, to the south. Further away from the city center, suburban towns like Wah and Taxila have also expanded, forming urban clusters of their own. [42]

G overnance

Punjab is one of Pakistan’s seven provinces; it contains thirty districts including Rawalpindi. [43] This district is further divided into “Tehsil”, which includes Rawalpindi city. The Pakistani capital, Islamabad, does not belong to any province and is a “twin city” to Rawalpindi, meaning the two are administered independently despite their geographic proximity. [44]

City Policy/Planning

The first major plan of the modern-day twin cities was drawn up by greek urban planner Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis in the 1960s, dividing the metropolitan area into three parts: Islamabad, Rawalpindi and the a national park to the east. This plan imposed a rigid grid on onto the area’s hilly landscape with the intention of guiding the city’s expansion. However, the plan’s implementation has depended on different agencies, resulting in a variety of development patterns across the area. More precisely, Islamabad is administered by the state-run Capital Development Authority (CDA) and Rawalpindi by the Rawalpindi Development Authority (RDA) or by the Punjab Housing, Urban, Development & Public Health Engineering Department (HUDPHED). [45]

Today, it is clear that the plan is not fully implemented. Although Most of Islamabad is clearly organized in a grid plan, the spatial planning of Rawalpindi has not followed the master plan as closely . A 2006 case study by Sajida Iqbal Maria and Muhammad Imran explains that although the master plan provided a detailed physical framework for development, it did not provide a framework for institutional development, and was thus somewhat unfeasible. THe administrative fragmentation of the Islamabad-Rawalpindi further contributes to the inefficiency of policymaking and poses a major obstacle to the implementation of the masterplan. [46]

Starting in the 1980s, another Master Plan was devised for Islamabad. Zoning laws were elaborated in 1992, dividing the city into five zones. The fifth zone was set South of the city, but no boundary was drawn to distinguish it from the urban area of Rawalpindi. [47] Yet again in 2005, a zoning regulation document for Islamabad represented the city’s zones and showed Rawalpindi as a completely separate entity. [48]

As for Rawalpindi, The RDA created the Guided Development Plan, whose main innovation was a ring road around the city’s urban areas. In 1998, the Punjab Housing and Physical Planning Department created a Masterplan for Rawalpindi. Similarly to Islamabad’s development, planning in Rawalpindi made room for expansion without considering the growth of its twin city. [49]

Private developers occupy an important role in the city’s expansion, especially in zones 2 and 5 of Islamabad. In some instances, developments are caught between the twin cities, as is the case for Bahria town, which is thus regulated by two sets of codes. [50]

One major difference between the two administrations is their way of managing informal settlements. Indeed, the CDA is demolishing informal settlements and displacing their inhabitants, whereas Rawalpindi has recognized some settlements in an effort to provide essential services to their populations. [51]

Both cities show some concern for environmental protection in their policies. Indeed, the RDA requires an Environmental Impact Assessment for the approval of urban developments and “complex buildings” occupying more than one hectare (20 Kanal). [52] The CDA mentions biodiversity efforts including tree plantings, and claims to make “concrete efforts to preserve the rich biodiversity” of the area. [53] However, there are major limitations to the efforts of both cities, seen as developments that are clearly encroaching upon rural and natural areas are moving ahead, and Islamabad specifically has destroyed 10,000 trees to make way for new developments. [54] Additionally, general issues like water management continue to pose a major threat to ecosystems in the area. [55]

Developments in the Islamabad-Rawalpindi, especially the construction of gated communities, has caused an increase in informal settlements due to the influx of construction workers need into the city. [56] Additionally, Gated communities are developed without consideration for biodiversity conservation. For instance, Bahria town is being built beyond the boundaries of Islamabad, onto what used to be lush woodlands of Rawalpindi. [57] The the Punjab Forest Department filed a complaint against the private developer because the project encroached upon the forest, and because officers who tried to bring attention to the project had been harassed and kidnapped. [58]

Some gated communities in the cities are being developed by the Defense housing Authority (DHA), which has the power to can take land to create housing for former military officials. [59] The DHA has developed areas south of the city in successive phases since 1992, and even has a masterplan of its own. [60]

The Tourism Development Corporation of Punjab has also created a master plan to develop Murree, a “pollution free tourist town,” north of Rawalpindi. Although the pakistani newspaper Dawn initially called the 2004 plan for the project an “environmental disaster,” the plan has been revised with help from organizations like the WWF, and now addresses biodiversity protection as a major concern. Nevertheless, the plan proposes to develop the project on natural lands, and the suggested conservation system does not appear to offset the biodiversity loss caused by Murree. Indeed, the project is to be built in the Patriata forest. Additionally, this forest constitutes a watershed that contributes to the supply of half the drinking water for the city. Therefore, despite the site’s successful conservation efforts, the project has still caused the degradation of a natural environment. [61] [62]

Many building developpements are given to private housing cooperatives such as the PIA, which is building a “society development” adjacent to Bahria, in Rawalpindi. These projects leave no room for natural vegetation. [63]

Additionally, although the government subsidizes some projects by providing cheap land to developers, such projects are usually reserved for state workers and are not open to the general public, let alone to those of lower social classes. [64]

Another project for Islamabad New City was to be developed in the Margalla Hills National park, with little concern for environmental issues. Although the project was abandoned , the NHA is trying to revive it for the potential revenue it could generate. [65]

Capital Smart City is a yet another development project that seeks to create a business district for Islamabad close to the new airport. Construction has started on a location far away from the current urban center. Despite claims of a sustainable and environmentally friendly project, the plan suggests that the project would leave no room for natural cover. Additionally, the development of a business district in the middle of rural lands seems like it would drastically accelerate the city’s sprawl. [66]

The Pakistan Vision 2025 acknowledges that zoning laws are out of date in the country, and seeks to promote the development of clean water, and energy and food security for Pakistanis. Biodiversity loss is mentioned as a consequence to population growth, and the document underlines the need to create “eco-friendly sustainable cities.” [67]

Therefore, though planning in the Islamabad-Rawalpindi area exists, high institutional fragmentation seems to deresponsibilize the agencies that try to guide the city’s development. Environmental and biodiversity concerns are frequently mentioned, but development plans are lacking real, concrete efforts to curb the city’s sprawl. In fact, the project for an urban center in the middle of rural Rawalpindi suggests that reducing sprawl is not a priority to local governments.

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

The latest version of the Pakistani National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) was written in 2017. The document lists five core objectives, which focus on mainstreaming biodiversity in the government and society, reducing direct pressures on biodiversity, safe-guarding ecosystems, increasing and sharing the benefits from ecosystem services, and improving implementation of conservation. [68]

An earlier draft of the NBSAP reveals that 52% of the actions listed on the 2000 Biodiversity Action Plan were not carried out, due to lack of will or of resources. [69] Pakistan lost 41.3% of its forest cover between 1990 and 2010. Ecosystem services still have not been integrated into planning, and ecosystems in the country have not been mapped by any authority. Additionally, most people living in rural areas are heavily dependant on the natural environment for fuel, forage and timber, and the government has yet to approve a national policy for the conservation or sustainable use of such ecosys t ems. [70]

The NBSAP identifies many obstacles to biodiversity conservation, most of them administrative. The plan explains that planning gives little priority to biodiversity and ecosystem services, and that the inability of the central government to manage large areas has placed a large responsibility onto local communities and institutions. Indeed, although the 1997 Pakistan Environmental Protection Act allowed the state to address conservation issues on a federal level, the 18th amendment to the Pakistani constitution in 2010 ultimately conferred most environmental legislative powers to provincial governments, as it sought to limit presidential powers and improve political stability in the country. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Climate Change, which has replaced the Ministry of Environment, will play an essential role in coordinating the efforts to reach the Aichi targets. [71]

The NBSAP identifies priority ecosystems for conservation, none of which are near the city. The plan lists the Western Himalayan Temperate Forests as one of two priority ecosystems in the country, and acknowledges the threat that urban sprawl poses to biodiversity, but also presents it as a potential “effective tool” for conservation if development planning includes natural areas. [72]

The Plan focuses on improving legal frameworks, expanding and connecting protected areas, empowering local communities for conservation, improving biodiversity knowledge, and mainstreaming the knowledge of pastoralists and nomads into management policies. Among its targets, the plan maintains the Aichi goal of protecting 17% of the country’s area, while also reducing the list of protected areas to only include areas that are actually effective. The document also aims to restore at least 20% of significant degraded ecosystems. Other targets include information management through a central GIS system, the identification of priority species, and their in- and ex-situ conservation. [73]

National

The Pakistani Ministry of Climate Change is responsible for biodiversity conservation on a national level. It is in charge of the Green Pakistan Programme, which was approved in 2016 and had already planted two million trees in the country a year later. [74] The programme includes a project in Ayubia park, north of the city, which focuses on vegetation improvement, sustainable grazing, fruit tree planting, slope stabilization and check dams. [75] The Ministry is also involved on the improvement of the Islamabad zoo and botanical gardens, which are to become a 725-acre center for entertainment and conservation. [76]

The Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC) is leading initiatives to rehabilitate rangelands through planting and managed grazing, in order to improve agricultural productivity, maintain ecosystem services and decrease soil erosion. [77]

Regional and Local

Although the Punjab province has an Environment Protection Department, it seems focused on pollution and waste management rather than biodiversity conservation. [78] Rawalpindi does not seem to have an Environment Department on the district or city scale, and the Rawalpindi Development Authority does not mention any environmental concerns aside from referencing the Water and Sanitation Agency (WASA). [79]

However, the Capital Development Authority has an Environment Wing, which leads multiple initiatives throughout the city. For instance, the department leads a tree plantation drive in an attempt to preserve the Margalla Hills National Park, and to maintain green belts and other green areas throughout the city. [80] The City of Islamabad has adopted the slogan “Islamabad the Beautiful,” and has worked on recording Banyan trees in Margalla and with NGOs to rehabilitate forest cover in the area. [81]

Protected Areas Near City

The most important protected area near the city is the IUCN-category V Margalla Hills National park (174km2) just north of the city. The park was changed from a wildlife sanctuary to a national park in 1979, and is currently threatened by poaching, logging, and urban expansion, namely hotel and resort developments. The increased popularity of the park has also caused the creation of a road, fragmenting the natural area. [82]

In the same conservation category as Margalla Hills, Ayubia National Park (reportedly 17 km2) does not seem like effective conservation areas. Indeed, leopard in Ayubia sustained by feeding on livestock, putting farmers at risk. [83] Aside from the category-IV Islamabad Wildlife Sanctuary (70km2), the rest of protected areas in the city are game reserves, and include the Khari Murat (56km2), Kathar (11km2), and Mori Said Aili (2.4km2) reserves. To the west of the city, protected areas are located deeper in the mountains, and the area immediately next to the city is not protected. [84] Finally, although not a significant conservation site, the Morgah Biodiversity Park plays an important role in raising awareness among locals, and in providing plants for medicinal research. [85]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is active in Pakistan, but its environmental programs are focused on reducing climate change rather than conserving biodiversity. [86] The organization is leading a Sustainable Land Management Programme to Combat Desertification, and aims to strengthen policies and incentives for land management, increasing institutional resource capacity, and improving the economic productivity of lands through the restoration of dry land ecosystems. [87]

WWF Pakistan also leads many projects in the Western Himalayan Area. The organization is working on restoring springs around Ayubia National Park, namly through forest rehabilitation. Awareness campaigns are also an essential component of WWF’s work in Pakistan, as well as research on species like leopards. [88]

Green Pakistan is an organization that focuses on raising awareness and lobbying through advocacy campaigns, but has also led tree planting projects since 1997. [89]

The Pakistan Wildlife Foundation works in the country to conserve and sustainably manage wildlife and to raise awareness on biodiversity issues. The Foundation publishes a magazine, Wildlife of Pakistan , as well as a research journal, the Pakistan Journal of Wildlife . Many of its activities are centered around the academic world, namely helping students access training courses and knowledge on biodiversity conservation. [90]

Some organizations in the country focus on specific species, like the Snow Leopard Trust. This organization functions in five countries including Pakistan, and its initiatives range from combating poaching to raising awareness and leading research and conservation programs. The organization partners with the Pakistan-based Snow Leopard Foundation, led by Dr. Muhammad Ali Nawaz of the Islamabad Quaid-i-Azam University. [91]

Public Awareness

Pakistan shows some level of awareness on biodiversity, but conservation is certainly not perceived as a priority. It seems as though the population is not aware of the impact that ecosystem protection could have on their daily lives, namely improved water supply, reduced pollution, and better agricultural productivity.

The NBSAP explains that previous efforts to raise awareness among politicians were ineffective, and biodiversity was never seen as a priority in policymaking. The plan suggests targeting political leaders who are very influential in their respective groups, and could help spread concern on conservation. The NBSAP’s strategies on awareness address mass media, education, and the specific importance of improving knowledge within the administration. [92]

Conclusion

The Rawalpindi-Islamabad area is starting to recognize the importance of biodiversity conservation, which is being carried out through a few forest rehabilitation projects and through the progressive improvement of the region’s protected area network. However, many problems persist, first and foremost of which is the uncontrolled sprawl of the city onto rural and natural lands.

The multiplicity of parties involved in city planning--various departments from two municipalities, and a handful of private developers-- constitutes a major obstacle to the control of the city’s growth. Although the upcoming publication of development plans for both cities brings hope that reducing sprawl and conserving ecosystems might become more of a priority, it seems that the city’s administration is bound to remain divided and as such inefficient.

In its NBSAP, Pakistan acknowledges the existing gap between the official list of protected areas and the area where protection is actually being enforced, and plans to fill that gap and further extend and connect protected areas. Yet again, administration poses a problem to such projects, since the 18th amendment, in trying to bring political stability to the country, has made it unclear who holds responsibility for protected areas.

Finally, the country admits that it did not succeed in implementing over half of the targets it set for itself in the 2000 NBSAP, due mainly to a lack of resources and of will. Thus, raising awareness among policymakers is an essential step in making the country’s current NBSAP a reality.

Therefore, despite clear progress and a will to improve the status of its natural areas, the first step in protecting the biodiversity of the Islamabad-Rawalpindi area is to bring clarity to its administrative structure, and to enforce the upcoming development plans.

[2] World Wildlife Fund, “India, Nepal, Pakistan,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0502 (accessed July 23, 2018)

[3] Encyclopedia Britannica, “Rawalpindi,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Rawalpindi (accessed July 23, 2018)

[4] CEPF. “Himalaya.” Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/himalaya.

[5] CEPF. “Himalaya.” Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/himalaya.

[6] CEPF. “Himalaya - Species.” Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/himalaya/species.

[7] CEPF. “Himalaya - Threats.” Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/himalaya/threats.

[8] CEPF. “Himalaya.” Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/himalaya.

[9] WWF. “India, Nepal, Pakistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0502.

[10] “Himalayan Brown Bears Now Critically Endangered.” euronews, January 6, 2014. https://www.euronews.com/2014/01/06/himalayan-brown-bears-now-critically-endangered.

[11] “Himalayan Brown Bear (Subspecies Ursus Arctos Isabellinus).” iNaturalist.org. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/147158-Ursus-arctos-isabellinus.

[12] WWF. “India, Nepal, Pakistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0502.

[13] “Western Himalayan Subalpine Conifer Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/40502.

[14] WWF. “Himalayan Subtropical Pine Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0301.

[15] WWF. “Himalayan Subtropical Pine Forests | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/im0301.

[16] “Himalayan Subtropical Pine Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/40301.

[17] WWF. “Indian Subcontinent--Pakistan, Afghanistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1307.

[18] WWF. “Indian Subcontinent--Pakistan, Afghanistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1307.

[19] Bear Conservation. “Baluchistan Bear.” Accessed July 28, 2019. http://www.bearconservation.org.uk/baluchistan-bear/.

[20] “Balochistan Black Bear.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. http://foreverindus.org/wwf2/species/BalochistanBlackBear.php.

[21] WWF. “Indian Subcontinent--Pakistan, Afghanistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1307.

[22] WWF. “Indian Subcontinent--Pakistan, Afghanistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1307.

[23] “Baluchistan Xeric Woodlands.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed July 28, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/81307.

[24] All About Sikhs, “Milkha Singh Thehpuria,” https://www.allaboutsikhs.com/pre-1800/milkha-singh-thehpuria (accessed July 23, 2018)

Encyclopedia Britannica, “Rawalpindi,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Rawalpindi (accessed July 23, 2018)

[25] Chloe Chaplain, “Indian Partition: A brief history of India and Pakistan on the 70th anniversary of independence,” EveningStandard (August 15, 2017) https://www.standard.co.uk/news/world/indian-partition-a-brief-history-of-india-and-pakistan-on-the-70th-anniversary-of-independence-a3612126.html

[26] Chloe Chaplain, “Indian Partition: A brief history of India and Pakistan on the 70th anniversary of independence,” EveningStandard (August 15, 2017) https://www.standard.co.uk/news/world/indian-partition-a-brief-history-of-india-and-pakistan-on-the-70th-anniversary-of-independence-a3612126.html

[27] Farahnaz Ispahani, Purifying the Land of the Pure: A History of Pakistan's Religious Minorities , (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), (Not sure what page, because taken from the free sample. One citation is “In Rawalpindi, where Muslims comprised 43.79…” (might help with a word search).) Also note: though the book focuses on religious tensions, the author was a member of the Pakistani parliament and was a lecturer at PennLaw in 2017, which might be a way to get in contact with policymakers. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jl7ODQAAQBAJ&pg=PT20&lpg=PT20&dq=rawalpindi+hindu&source=bl&ots=bByA-ab7k_&sig=zDIxZj8PNkV_UwNTGQzCrXMD834&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiq-MOqmPrXAhUI52MKHbWLAw44HhDoAQgvMAE#v=onepage&q=rawalpindi%20hindu&f=false

[28] Saad Khan, “Islamabad’s 50 Years: A DOwnward Spiral in Urban Planning,” Huffington Post (May 25, 2011), https://www.huffingtonpost.com/saad-khan/islamabads-50-years-a-dow_b_434538.html

[29] Bilal Hakim, “Gasping for Air: Here’s How Major Pakistani Cities Rank for Air Pollution,” ProPakistani (2017), https://propakistani.pk/2017/01/24/gasping-air-heres-major-pakistani-cities-rank-air-pollution/

[30] “Islamabad sees deteriorating air quality: report,” Pakistan Today (April 2, 2018) https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2018/04/02/islamabad-sees-deteriorating-air-quality-report/

[31] H. Nisar et al., “Impacts of Solid Waste Management in Pakistan: A Case Study of Rawalpindi City,” in M. Zamorano et al. (eds) Waste Management and the Environment IV , WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 109 (Southhampton: 2008), (quite unsure about this citation) https://www.witpress.com/elibrary/wit-transactions-on-ecology-and-the-environment/109/19017

[32] Sehrish Wasif, “Microbial contamination of drinking water in Islamabad has intensified, claims report,” The Express Tribune (September 24, 2017) https://tribune.com.pk/story/1514640/microbial-contamination-drinking-water-islamabad-intensified-claims-report/

Ben Franklin Health District, “What are Nitrates,” http://www.bfhd.wa.gov/info/nitrate-nitrite.php (accessed July 23, 2018)

[33] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan Draft,” 2015

[34] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan Draft,” 2015

[35] EARTH

[36] Danish Hussain, “Slum Survey: Over 80,000 people living in capital’s katchi abadis, says report,” The Express Tribune (February 27, 2014), https://tribune.com.pk/story/676555/slum-survey-over-80000-people-living-in-capitals-katchi-abadis-says-report/.

[37] Ayesha Noor, “Slums in Islamabad,” Voice of Journalists (May 17, 2015) https://www.voj.news/slums-in-islamabad/.

[38] Amiera Sawas et al., “Urbanization, Gender and Violence in Rawalpindi and Islamabad: A Scoping Study,” 2014.

[39] Ayesha Noor, “Slums in Islamabad,” Voice of Journalists (May 17, 2015) https://www.voj.news/slums-in-islamabad/.

[40] Amiera Sawas et al., “Urbanization, Gender and Violence in Rawalpindi and Islamabad: A Scoping Study,” 2014.

[41] “Ten major cities’ population up by 74pc,” Pakistan Today (August 28, 2017) https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2017/08/28/ten-major-cities-population-up-by-74pc/.

[42] EARTH

[43] Lodhran.pk, “Map of Punjab,” http://lodhran.pk/punjab-map.aspx (accessed July 23, 2018).

Maps Pakistan, “Pakistan Map 2016” https://maps-pakistan.com/pakistan-map-2016 (accessed July 23, 2018)

[44] Amiera Sawas et al., “Urbanization, Gender and Violence in Rawalpindi and Islamabad: A Scoping Study,” 2014.

[45] Sajida Iqbal Maria and Muhammad Imran, “Planning of Islamabad and Rawalpindi: what went wrong?,” 42nd ISoCaRP Congress 2006 (Istanbul: 2006)

Housing, Urban Development & Public Health Engineering Department, “Overview,” https://hudphed.punjab.gov.pk/overview (accessed July 23, 2018)

[46] Sajida Iqbal Maria and Muhammad Imran, “Planning of Islamabad and Rawalpindi: what went wrong?,” 42nd ISoCaRP Congress 2006 (Istanbul: 2006)

[47] Housing, Urban Development & Public Health Engineering Department, “Overview,” https://hudphed.punjab.gov.pk/overview (accessed July 23, 2018)

[48] Capital Development Authority, “Islamabad Capital Territory (Zoning) Regulation,” 2005

Capital Development Authority, “Islamabad Capital Territory Map,” http://www.cda.gov.pk/housing/ictmap.asp (accessed July 23, 2018)

[49] Housing, Urban Development & Public Health Engineering Department, “Overview,” https://hudphed.punjab.gov.pk/overview (accessed July 23, 2018)

[50] Housing, Urban Development & Public Health Engineering Department, “Overview,” https://hudphed.punjab.gov.pk/overview (accessed July 23, 2018)

[51] Rawalpindi Development Authority, “Rawalpindi Development Authority Building and Zoning Regulations,” 2007

[52] Rawalpindi Development Authority, “Rawalpindi Development Authority Building and Zoning Regulations,” 2007

[53] Capital Development Authority, “Tree Plantation Drive,” http://www.cda.gov.pk/projects/environment/Tree_Plantation/ (accessed July 23, 2018)

[54] “Another 100 trees chopped down in Islamabad,” Dawn (January 22, 2008), https://www.dawn.com/news/285822/another-100-trees-chopped-down-in-islamabad

[55] Saad Khan, “Islamabad’s 50 Years: A DOwnward Spiral in Urban Planning,” Huffington Post (May 25, 2011), https://www.huffingtonpost.com/saad-khan/islamabads-50-years-a-dow_b_434538.html

[56] Haseb Asif, “What lies behind the gates of Pakistan’s elite communities,” Herald (July 29, 2016), https://herald.dawn.com/news/1153455

[57] Bahria Town, “About Rawalpindi,” http://www.bahriatown.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=108&Itemid=87 (accessed July 23, 2018).

Haseb Asif, “What lies behind the gates of Pakistan’s elite communities,” Herald (July 29, 2016), https://herald.dawn.com/news/1153455

[58] Haseb Asif, “What lies behind the gates of Pakistan’s elite communities,” Herald (July 29, 2016), https://herald.dawn.com/news/1153455

[59] Defence Housing Authority, “Home,” http://www.dhai.com.pk/ (July 23, 2018)

[60] Defence Housing Authority, “Home,” http://www.dhai.com.pk/ (July 23, 2018)

[61] TDCP, “Master Plan to Develop Murree, a Pollution Free Tourist Town 2031, Analysis & Policy Recommendation” (June 2013).

[62] Climate Change Division, Government of Pakistan, “Fifth National Report, Progress on CBD Strategic Plan 2010-2020 and Aichi Biodiversity Targets” (March 2014)

https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/pk/pk-nr-05-en.pdf

[63] PIA Officers Cooperative Housing Society, “Home,” http://www.piaochs.com.pk/index.html# (accessed July 24, 2018)

[64] Haseb Asif, “What lies behind the gates of Pakistan’s elite communities,” Herald (July 29, 2016), https://herald.dawn.com/news/1153455

[65] Syed Irfan Raza, “Smell of money attracts sharks: Reviving Islamabad New City Scheme,” Dawn (November 17, 2008), https://www.dawn.com/news/330342

[66] The Land Associates, “Development Status of Capital Smart City islamabad,” http://bahriatownprojects.com/development-update-capital-smart-city-islamabad/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

Manahil Estate, “Capital Smart City Islamabad - Project Details, Location and Plot Prices,” http://manahilestate.com/capital-smart-city-islamabad-project-details-location-plot-prices/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

[67] Pakistan Vision 2025 (website down, can also check https://www.pc.gov.pk/web/vision )

[68] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and action Plan,” 2017.

[69] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan Draft,” 2015

[70] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan Draft,” 2015

[71] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and action Plan,” 2017

[72] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and action Plan,” 2017

[73] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and action Plan,” 2017

[74] http://www.mocc.gov.pk/frmDetails.aspx (site down)

Khawar Ghumman, “PM approves launching of ‘Green Pakistan Programme’ to add 100 million plants over the next five years,” Dawn (March 5, 2016), https://www.dawn.com/news/1243668

“Over two million trees planted under GPP,” Pakistan Observer (July 2, 2017), http://pakobserver.net/two-million-trees-planted-gpp/

[75] Environment & Disaaster Management, “Looking Upstream to Manage Flood Risk: A Pakistan Example,” http://envirodm.org/post/looking-upstream-to-manage-flood-risk-a-pakistan-example (accessed july 24, 2018)

[76] http://www.mocc.gov.pk/frmDetails.aspx (site down)

Subh-e-nau, “Projects,” http://greenpakistan.org/projects/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

[77] Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, “Rangeland Rehabilitation Initiatives,” http://www.parc.gov.pk/files/New-Initiatives/13.pdf (accessed July 24, 2018)

[78] Punjab Environment Protection Department, “Environmental Issues,” https://epd.punjab.gov.pk/environmental_issues (accessed July 24, 2018).

[79] Rawalpindi Development Authority, “Directorates,” http://www.rda.gop.pk/directorates/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

[80] Capital Development Authority, “Tree Plantation Drive,” http://www.cda.gov.pk/projects/environment/Tree_Plantation/ (accessed July 23, 2018)

[81] http://www.visitislamabad.net/islamabad/files/news.asp?var=236 (site down)

City of Islamabad, “Students of Geography Department of IMCG, F-7/4 visit CDA Headquarters,” http://www.visitislamabad.net/islamabad/files/news.asp?var=135 (accessed July 24, 2018).

[82] Suhail Yusuf, “Distress Call: Wildlife at Margalla Hills under Threat,” Dawn (January 23, 2015), https://www.dawn.com/news/1155083

[83] Conservation Corridor, “What is behind leopard attacks in northwest Pakistan?,” http://conservationcorridor.org/2017/02/what-is-behind-leopard-attacks-in-pakistan/ (accessed July 24, 2018).

[84] PROTECTED PLANET

[85] “Rawalpindi: Biodiversity Park to Help Conserve Ecosystem,” Dawn (February 2, 2005)

Riffat Naseem Malik et al., “Ethonobotanical properties and uses of Medicinal Plants of Morgah Bidoiversity Park, Rawalpindi,” Pakistan Journal of Botany 40, 5 (2008).

[86] UNDP Pakistan, “Environment and Climate Change,” http://www.pk.undp.org/content/pakistan/en/home/ourwork/environmentandenergy/overview.html (accessed July 24, 2018).

[87] UNDP Pakistan, “Sustainable Land Management to Combat Desertification in Pakistan (SLMP)” http://www.pk.undp.org/content/pakistan/en/home/library/evaluation-reports/sustainable-land-management-to-combat-desertification-in-pakista.html (accessed July 24, 2018).

[88] WWF Pakistan, “Western Himalayan,” http://www.wwfpak.org/ecoregions/westernhimalayan.php (accessed July 24, 2018)

[89] Subh-e-nau, “Projects,” http://greenpakistan.org/projects/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

[90] Pakistan Wildlife Foundation, “Objectives,” http://www.wildlife.org.pk/about/objectives/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

Pakistan Wildlife Foundation, “Activities,” http://www.wildlife.org.pk/about/our-activities/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

[91] Snow Leopard Trust, “Pakistan,” https://www.snowleopard.org/our-work/where-we-work/pakistan/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

Snow Leopard Foundation, “About us,” http://slf.org.pk/ (accessed July 24, 2018)

[92] Government of Pakistan, “Pakistan National Biodiversity Strategy and action Plan,” 2017