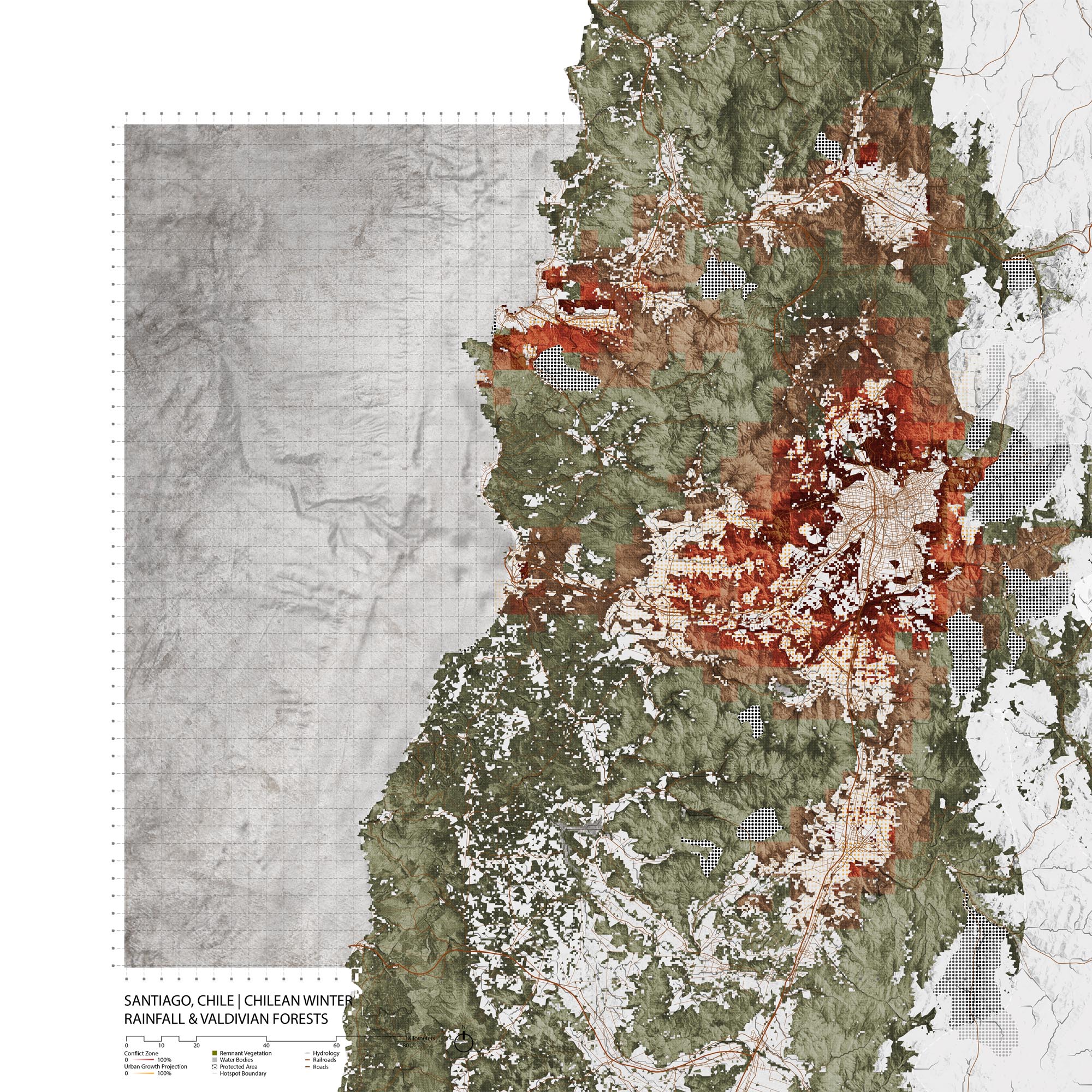

Santiago, Chile

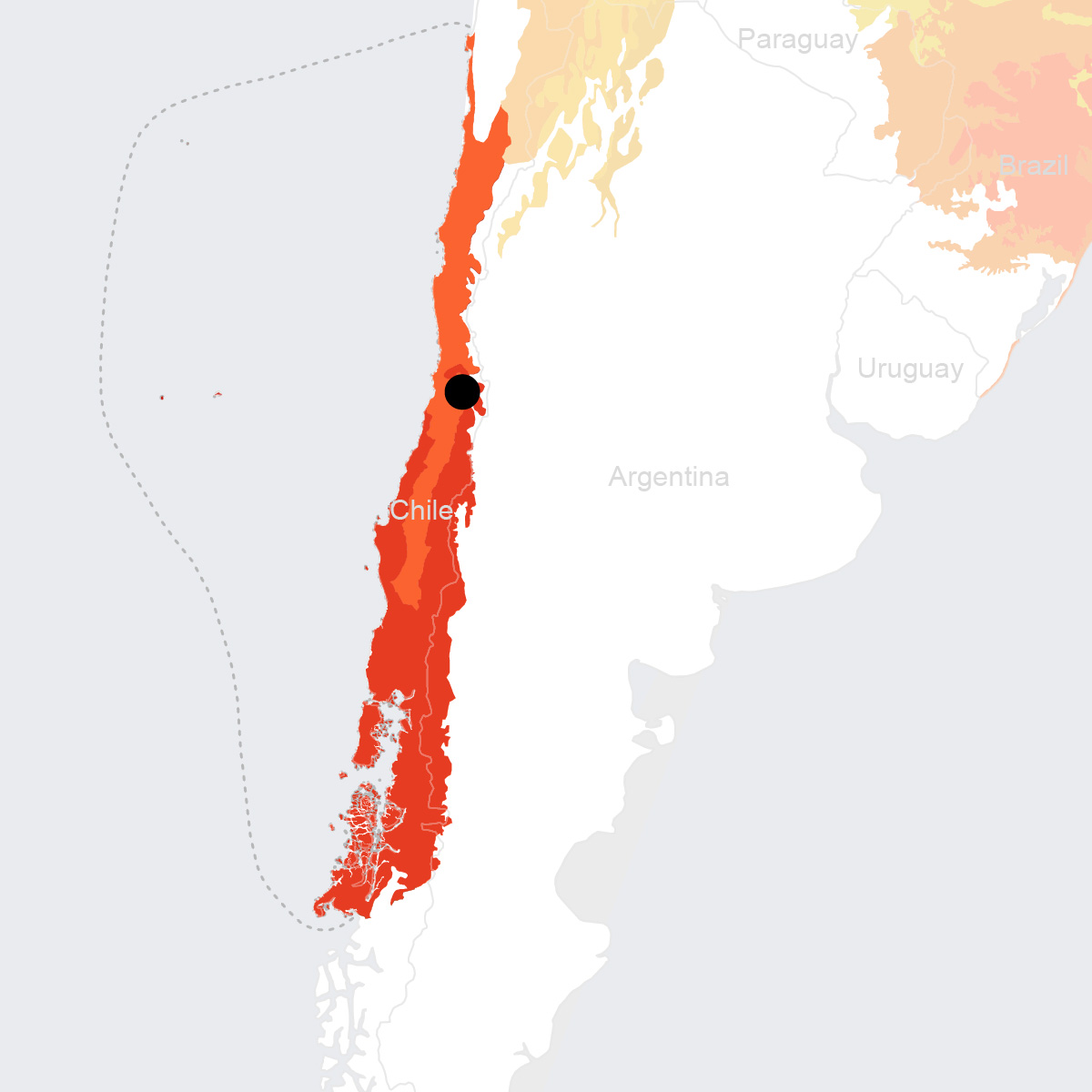

- Global Location plan: 33.45oS, 70.67oW

- Hotspot: Chilean Winter Rainfall and Valdivian Forests

- Population 2015: 6,507,000

- Projected population 2030: 7,122,000

- Mascot species: Chile’s national flower, the copihue (Lapageria rosea) & the Culpeo, the South American Fox (Lycalopex culpaeus)

- Primary Crops: grapes, potatoes, beans, wheat, maize, berries[1]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Pleurodema thaul

- Xenopus laevis

- Alsodes tumultuosus

- Rhinella spinulosa

- Alsodes montanus

- Calyptocephalella gayi

- Pleurodema bufoninum

- Calyptocephalella gayi

- Rhinoderma rufum

- Rhinella arunco

- Batrachyla taeniata

- Odontophrynus occidentalis

- Alsodes cantillanensis

- Alsodes nodosus

Mammals

- Tympanoctomys barrerae

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Mesoplodon grayi

- Microcavia australis

- Leopardus colocolo

- Leopardus geoffroyi

- Leopardus guigna

- Tadarida brasiliensis

- Phocoena spinipinnis

- Abrocoma vaccarum

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Thylamys elegans

- Lyncodon patagonicus

- Lasiurus cinereus

- Arctocephalus philippii

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Oligoryzomys longicaudatus

- Phyllotis xanthopygus

- Ctenomys johannis

- Ctenomys validus

- Tursiops truncatus

- Lycalopex griseus

- Conepatus chinga

- Lasiurus varius

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Lagenorhynchus obscurus ssp. posidonia

- Lagenorhynchus obscurus

- Mus musculus

- Grampus griseus

- Loxodontomys micropus

- Abrothrix andinus

- Histiotus montanus

- Spalacopus cyanus

- Lontra felina

- Lepus europaeus

- Orcinus orca

- Chelemys megalonyx

- Puma concolor

- Lagidium viscacia

- Lagostomus maximus

- Berardius arnuxii

- Galictis cuja

- Histiotus macrotus

- Delphinus delphis

- Mesoplodon traversii

- Euneomys petersoni

- Abrocoma bennettii

- Eligmodontia morgani

- Akodon spegazzinii

- Zaedyus pichiy

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Eubalaena australis

- Lissodelphis peronii

- Myotis dinellii

- Phyllotis darwini

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Chaetophractus villosus

- Lycalopex culpaeus

- Kogia sima

- Loxodontomys pikumche

- Octodon bridgesi

- Octodon lunatus

- Abrothrix longipilis

- Caperea marginata

- Cephalorhynchus eutropia

- Desmodus rotundus

- Abrothrix olivaceus

- Myocastor coypus

- Myotis chiloensis

- Octodon degus

- Chelemys macronyx

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Balaenoptera physalus

- Thylamys pallidior

- Euneomys mordax

- Ctenomys pontifex

- Globicephala melas

- Kogia breviceps

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Lama guanicoe

- Lagenorhynchus australis

- Lagenorhynchus cruciger

- Otaria byronia

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Chilean Winter Rainfall and Valdivian Forests cover the central-northern part of Chile and the far western edge of Argentina, stretching from the Pacific coast to the crest of the Andean mountains. The biodiversity hotspot also encompasses the San Félix, San Ambrosio, and the Juan Fernández islands. [2]

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~4,000 |

~50% |

- Chile’s national flower, the copihue ( Lapageria rosea ), monkey puzzle tree ( Araucaria araucana ) |

|

Birds |

>225 |

~12 |

|

|

Mammals |

~70 |

15 |

|

|

Reptiles |

>40 |

~66% |

|

|

Amphibians |

>40 |

~75% |

- Endangered Darwin’s frog ( Rhinoderma darwinii ) [4] , Critically Endangered Northern Darwin’s frog ( R. rufum ) [5] |

|

Freshwater Fishes |

>40 |

2 families |

|

About 30 percent of the Chilean Winter Rainfall and Valdivian Forests’ original vegetation remains in pristine condition. However, the hotspot faces increasing pressure from human activities and development. Deforestation first began in the 16

th

century by Spanish colonists, and since the 1970s large-scale plantations have further spurred much clearing. Large areas are burned each year, menacing these ecosystems which are not adapted to fire. Overgrazing, by both domestic animals and introduced species, has also contributed to heavy degradation of habitats. Other sources of destruction include invasive weeds, perennial weeds, and illegal trade of animals.

[6]

The Valdivian Temperate Forest

The Valdivian temperate forest ecoregion is famed for its plants’ extraordinary endemism and great antiquity of the biogeographic relationships. Its taxa show connections with other biotas in Oceania and are separated by the Andes from others of South America. The ecoregion covers a narrow strip of land between the western slopes of the Andes and the Pacific Ocean, running from 35° S to 48° S. Three geological features define this ecoregion – 1. The Andes range, with mountains above 3,000 m and frequent volcanic and seismic activities. 2. The coastal belt 100km to the west of and parallel to the Andes. These mountains are of elevations at max 1,300m. 3. The intermediate depression area (100-200m), covered by volcanic ash and glacial morainic fields. Soils of the two ranges are both poorly developed. [7]

The South American temperate forests present a high diversity of plant families (nearly 50% of all Chilean flora) and high endemism levels in taxa. Another distinctive trait is the high rate (about 85%) of pollination of flowers and woody plants by animals. Close to 20% of the woody plant genera produce red tubular flowers that are visited by Sephanoides sephaniodes , the only species of hummingbird that lives in these temperate forests. A majority of them also bears fleshy fruits, indicating the importance of seed dissemination by fruit-eating vertebrates. [8]

Forest cover in the ecoregion has declined by a-third after the arrival of Spanish colonists, and 50% of remaining patches correspond to only secondary forests. Despite the establishment of protected areas, there is a great disparity between their locations and the geographic distribution of trees and vertebrates; less than 10 percent of protected areas are in regions of the highest biodiversity levels. In addition, areas of the greatest wealth of species collide precisely with those of high density of human population, hence they are seriously pressured by agriculture and plantation forestry. There is nearly none protected areas in the in-between valleys. Main threats in the ecoregion include logging, monocultures, and large-scale roadworks (e.g. the southern coastal highway). Exports of reptiles and amphibians have also increased. Other pressures come from tourism and invasive exotic species. [9] At present, the Aichi target is met by 22 percent of area protection and a 10.31 percentage of terrestrial connectivity. [10]

Environmental History

In addition to Chile’s physical geography, biodiversity is high because of forest isolation beginning in the mid-Tertiary and rapid cooling and warming cycles that changed forest coverage. [11] These geologic events made Chile’s ecosystems unique to the world. The first human groups to settle in the Santiago were nomadic hunter-gatherers travelling inland in search of guanacos. The first sedentary settlements formed through farming and domestication along the Mapacho River. [12] These villages were eventually subject to the Incan Empire and were sites to gold and copper mining. Santiago was officially founded in 1541 and grew thereafter, despite frequent earthquakes, floods, and attacks from indigenous people. Santiago initially had a grid layout. In 1798, under colonial rule, embankments were constructed to prevent flooding from the Mapocho River.

Chile became a republic after the Chilean War of Independence, with Santiago as its capital. The 19th century saw population increase, an industrial boom, suburban growth to the south and west of the city, road infrastructure, a sewage system, and railway networks. [13] Silver and coal mining changed the landscape and provided immense wealth to the growing city. Although the 1960s saw plans that restricted the growth of Santiago, more land was set aside for urban development after the coup of 1973. Under Pinochet, sprawl increased as those living in informal settlements or rental tenements often were forced to relocate to the far south of Santiago. [14] Population and developed land continue to grow. Santiago’s dangerous levels of air pollution come from automobiles, industry (including processing centers for mined metal), and agriculture. [15]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Deforestation, caused by varying factors, is the main challenge that the Santiago region faces in conserving its biodiversity. Accidental and intentional forest fires disrupt established ecosystems and destroy native habitats, allowing invasive species to dominate the deforested area. [16] Forests are cleared for timber and to make room for agriculture, grazing, and infrastructure. Many homes in the region still use forests for heating and cooking, which also contributes to air pollution.

Santiago is the third most polluted city in the world; industrial and vehicular emission is made worse by Chile’s geographical position between mountains and coast that trap pollutants in the air. [17] In addition to forest fires and firewood and agricultural burning, pollution in Santiago is caused by vehicles, power plants, and other industrial processes.

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Santiago throughout its history has grown expansively and urbanized quickly. Today, over 40% of Chile’s 17 million people live in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, which risks stressing the infrastructure and natural resources of the highly populated areas. [18] Economic growth and urban development occurs without much planning or design, leading to consequences such as congestion and rampant construction. [19] Sprawling development of the periphery began in the 1950s and peaked in the 1980s. [20] Spatially, the city is running out of land to develop and green space is the city’s poorer areas are lacking.

Informal growth has been a policy issue in Santiago for a long time, partly because of the speed of Santiago’s urban growth and inability for local authorities to keep up with the housing demand. Policies ranged from violent relocations for private development under Pinochet and formalizing settlements in the democratic period up to 2006. [21] Today, coverage of drinking water, sewage, and wastewater treatment are almost 100% and the housing deficit is virtually eliminated quantitatively. [22]

Governance

Chile is a constitutional republic with a bicameral legislature and independent judiciary. The current constitution was voted in during Pinochet’s military government, but has been amended under their current democratic government. Chile is divided into regions, then further into provinces and communes. Santiago is in the Santiago province in Santiago Metropolitan Region, which are both run by the same intendant, chosen by the president. In 2001, the responsibilities of a provincial governor were given to a Provincial delegate, who functions on behalf of the intendant. Greater Santiago, which includes the majority of Santiago province, lacks a coherent metropolitan government for its administration. The existence of various authorities complicate the operation of the metropolitan are as a single entity.

City Policy/Planning

Development Plan

Santiago has no unified development authority and no governmental development plan. The intendente has no authority or funds to coordinate between municipalities and projects. [23]

Santiago is a part of 100 Resilient Cities and produced a resilience strategy in 2017. [24] The emphasis of the strategy is on improving governing capacity. The pillars of Santiago’s plan are mobility, environment, security, risk management, social equity, and economic development and competitiveness. Of those relating to the environment, most are focused on pollution and earthquakes. There are, however, sites identified for biodiversity conservation and recommendations for water ecosystem protection.

Zoning

Development in Santiago is restricted partially by zoning, which on a city wide level prescribes how much land can be developed. While there is no unified development plan or city planning authority, municipalities sometimes have their own zoning requirements and plans. [25] These vary by municipalities with no coordination between them, resulting in mismatched urban spaces. In addition, a variance called "DFL-2 de construcción simultánea" allows for private developers to override certain municipal codes, which leads to suburban forms of car dependency and sprawl in Santiago. [26]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Chile’s most recent NBSAP was adopted on January 5, 2018, following the original in 2003. The first NBSAP was implemented from 2003 to 2010 and produced, among other outcomes, three thematic instruments, namely, the National Policy for the Protection of Threatened Species, National Strategy for the Conservation and Rational Use of Wetlands, and the National Policy on Protected Areas. The new plan outlines 5 objectives for 2030: to promote sustainable use of biodiversity for human wellbeing, reducing threats to ecosystems and species; to increase participation regarding biodiversity; to establish robust institutions and the equitable sharing of biodiversity benefits; to include biodiversity objectives in public- and private-sector policies, plans and programs; and to protect and restore biodiversity and its ecosystem services. [27]

Protected Areas

The main conservation agency is the Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF), which is managed and funded by the Ministry of Agriculture. CONAF manages the Sistema Nacional de Áreas Silvestres Protegidas (Snaspe). Within Snaspe, Chile has three principal categories of protection: parques nacionales (national parks), reservas nacionales (national reserves), and monumentos naturales (natural monuments). [28] In addition, Chilean law allows the establishment of private natural reserves (reservas naturales privadas or santuarios de la naturaleza), which are growing in number and importance.

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) is an international organization that helps funnel private and public sector money towards biodiversity initiatives. [29] Biofin Chile is administered and executed directly by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). [30] Results so far include various reports on Chile’s biodiversity, agreements and coordination with other biodiversity initiatives, implemented a pilot mechanism to facilitate sustainable agriculture practices in the private sector. [31]

Public Awareness

Public awareness of biodiversity seems to be generally low in relation to their press freedom. Santiago is a highly polluted, heavily industrialized, car-based region, so much of the attention paid to the environment is centered around how it directly affects humans instead of the ecosystem as a whole. In addition, there is no coordinated national or regional authority tasked with preserving biodiversity so information is lacking. There is also a lack of public participation in environmental issues.

[1] New Agriculturalist, “Country profile - Chile,” http://www.new-ag.info/en/country/profile.php?a=846; Encyclopedia Britannica, “Santiago,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Santiago-region-Chile (accessed September 19, 2018)

[2] CEPF. “Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/chilean-winter-rainfall-valdivian-forests.

[3] CEPF. “Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests - Species.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/chilean-winter-rainfall-valdivian-forests/species.

[4] “Rhinoderma Darwinii (Darwin’s Frog).” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/19513/79809372.

[5] “Rhinoderma Rufum (Northern Darwin’s Frog).” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/19514/79809567.

[6] CEPF. “Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests - Threats.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/chilean-winter-rainfall-valdivian-forests/threats.

[7] WWF. “Southern South America: Chile and Argentina | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0404.

[8] WWF. “Southern South America: Chile and Argentina | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0404.

[9] WWF. “Southern South America: Chile and Argentina | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed July 26, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0404.

[10] “Valdivian Temperate Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed July 26, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/60404.

[11] ibid.

[12] This is Chile, “Brief history of Santiago,” https://www.thisischile.cl/brief-history-of-santiago/?lang=en (accessed October 3, 2018)

[13] ibid.

[14] Mary M Shirley, Thirsting for Efficiency: The Economics and Politics of Urban Water System Reform (Oxford: Elsevier Science, 2002), 193

[15] Council on Hemispheric Affairs, “The Battle to Breathe: Chile’s Toxic Threat,” http://www.coha.org/the-battle-to-breathe-chiles-toxic-threat/ (accessed October 3, 2018)

[16] CEPF, “CHILEAN WINTER RAINFALL-VALDIVIAN FORESTS - SPECIES,” https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/chilean-winter-rainfall-valdivian-forests/species (accessed September 28, 2018)

[17] Moon, “Environmental Issues in CHile,” https://moon.com/2014/02/environmental-issues-in-chile/ (accessed October 10, 2018)

[18] The Santiago Times, “Chile’s population swella to 17 million,” https://santiagotimes.cl/2017/09/01/chiles-population-swells-to-17-million/ (accessed October 17, 2018)

[19] AmCham Chile, “Urban Planning in Santiago”, https://www.amchamchile.cl/en/2012/06/planificacion-urbana-en-santiago-2/ (accessed Ocrtober 17, 2018)

[20] https://web.uchile.cl/vignette/revistaurbanismo/n1/13.html

[21] http://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/118191/jiron_rethinking.pdf?sequence=1

[22] AmCham Chile, “Urban Planning in Santiago”, https://www.amchamchile.cl/en/2012/06/planificacion-urbana-en-santiago-2/ (accessed Ocrtober 17, 2018)

[23] ibid.

[24] http://www.100resilientcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Santiago-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf

[25] AmCham Chile, “Urban Planning in Santiago”, https://www.amchamchile.cl/en/2012/06/planificacion-urbana-en-santiago-2/ (accessed Ocrtober 17, 2018)

[26] https://web.uchile.cl/vignette/revistaurbanismo/n1/13.html

[27] Convention on Biological Diversity, “Chile” https://www.cbd.int/nbsap/about/latest/default.shtml#cl (accessed October 24, 2018)

[28] Moon, “Environmental Issues in CHile,” https://moon.com/2014/02/environmental-issues-in-chile/ (accessed OCtober 24, 2018)

[29] http://www.biodiversityfinance.net/about-biofin/what-biodiversity-finance

[30] https://biofinchile.cl/antecedentes/

[31] https://biofinchile.cl/resultados/