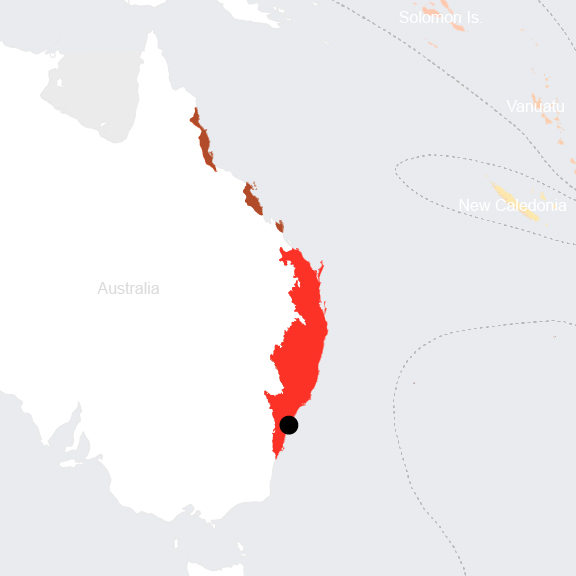

Sydney, Australia

- Global Location plan: 33.87oS, 151.21oE

- Ecoregion: Eastern Australian Temperate Forests

- Population 2015: 4,505,000

- Projected population 2030: 5,301,000

- Mascot Species: Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus)

- Primary Crops: mostly wheat, with substantial production of barley, cotton, canola, and grain sorghum[1]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Litoria verreauxii

- Limnodynastes fletcheri

- Litoria nasuta

- Litoria jervisiensis

- Limnodynastes salmini

- Uperoleia tyleri

- Litoria chloris

- Litoria littlejohni

- Crinia tinnula

- Crinia parinsignifera

- Limnodynastes dumerilii

- Limnodynastes interioris

- Limnodynastes peronii

- Limnodynastes tasmaniensis

- Limnodynastes terraereginae

- Uperoleia rugosa

- Litoria platycephala

- Litoria phyllochroa

- Litoria brevipalmata

- Lechriodus fletcheri

- Pseudophryne bibronii

- Mixophyes balbus

- Mixophyes iteratus

- Crinia signifera

- Litoria aurea

- Litoria castanea

- Litoria dentata

- Litoria lesueurii

- Litoria freycineti

- Litoria raniformis

- Mixophyes fasciolatus

- Litoria booroolongensis

- Litoria caerulea

- Litoria citropa

- Litoria ewingii

- Litoria fallax

- Litoria peronii

- Neobatrachus sudelli

- Notaden bennettii

- Paracrinia haswelli

- Uperoleia fusca

- Uperoleia laevigata

- Litoria wilcoxii

- Platyplectrum ornatum

- Litoria latopalmata

- Adelotus brevis

- Heleioporus australiacus

- Pseudophryne australis

- Litoria nudidigita

Mammals

- Sminthopsis murina

- Mormopterus planiceps

- Megaptera novaeangliae

- Mesoplodon ginkgodens

- Mesoplodon grayi

- Mesoplodon hectori

- Mesoplodon layardii

- Myotis macropus

- Phascolarctos cinereus

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Rattus fuscipes

- Rhinolophus megaphyllus

- Cercartetus nanus

- Melomys cervinipes

- Thylogale stigmatica

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Macropus rufogriseus

- Petrogale penicillata

- Ozimops petersi

- Trichosurus cunninghami

- Peponocephala electra

- Tursiops truncatus

- Tursiops aduncus

- Pseudomys gracilicaudatus

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Balaenoptera musculus

- Pseudocheirus peregrinus

- Falsistrellus tasmaniensis

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Miniopterus australis

- Chalinolobus morio

- Lagenorhynchus obscurus

- Mus musculus

- Myotis australis

- Mormopterus norfolkensis

- Austronomus australis

- Grampus griseus

- Vespadelus troughtoni

- Vespadelus darlingtoni

- Hydromys chrysogaster

- Vespadelus vulturnus

- Globicephala macrorhynchus

- Macropus robustus

- Saccolaimus flaviventris

- Chalinolobus dwyeri

- Potorous tridactylus

- Syconycteris australis

- Lepus europaeus

- Orcinus orca

- Wallabia bicolor

- Vombatus ursinus

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Scotorepens greyii

- Phascogale tapoatafa

- Pteropus poliocephalus

- Pteropus scapulatus

- Hyperoodon planifrons

- Berardius arnuxii

- Macropus giganteus

- Arctocephalus forsteri

- Isoodon obesulus

- Sminthopsis crassicaudata

- Isoodon macrourus

- Isoodon macrourus

- Trichosurus caninus

- Trichosurus vulpecula

- Tachyglossus aculeatus

- Mesoplodon mirus

- Delphinus delphis

- Mesoplodon traversii

- Petaurus norfolcensis

- Aepyprymnus rufescens

- Planigale maculata

- Perameles nasuta

- Acrobates pygmaeus

- Mormopterus ridei

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Antechinus stuartii

- Petauroides volans

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Mesoplodon densirostris

- Vulpes vulpes

- Eubalaena australis

- Lissodelphis peronii

- Ornithorhynchus anatinus

- Antechinus flavipes

- Thylogale thetis

- Vespadelus pumilus

- Nyctophilus geoffroyi

- Nyctophilus gouldi

- Balaenoptera borealis

- Kogia sima

- Mesoplodon bowdoini

- Scotorepens balstoni

- Antechinus swainsonii

- Antechinus agilis

- Arctocephalus pusillus

- Caperea marginata

- Scoteanax rueppellii

- Chalinolobus gouldii

- Dasyurus maculatus

- Vespadelus regulus

- Macropus parma

- Pseudomys novaehollandiae

- Pteropus alecto

- Petaurus australis

- Petaurus breviceps

- Balaenoptera edeni

- Balaenoptera physalus

- Globicephala melas

- Kogia breviceps

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Scotorepens orion

- Rattus lutreolus

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

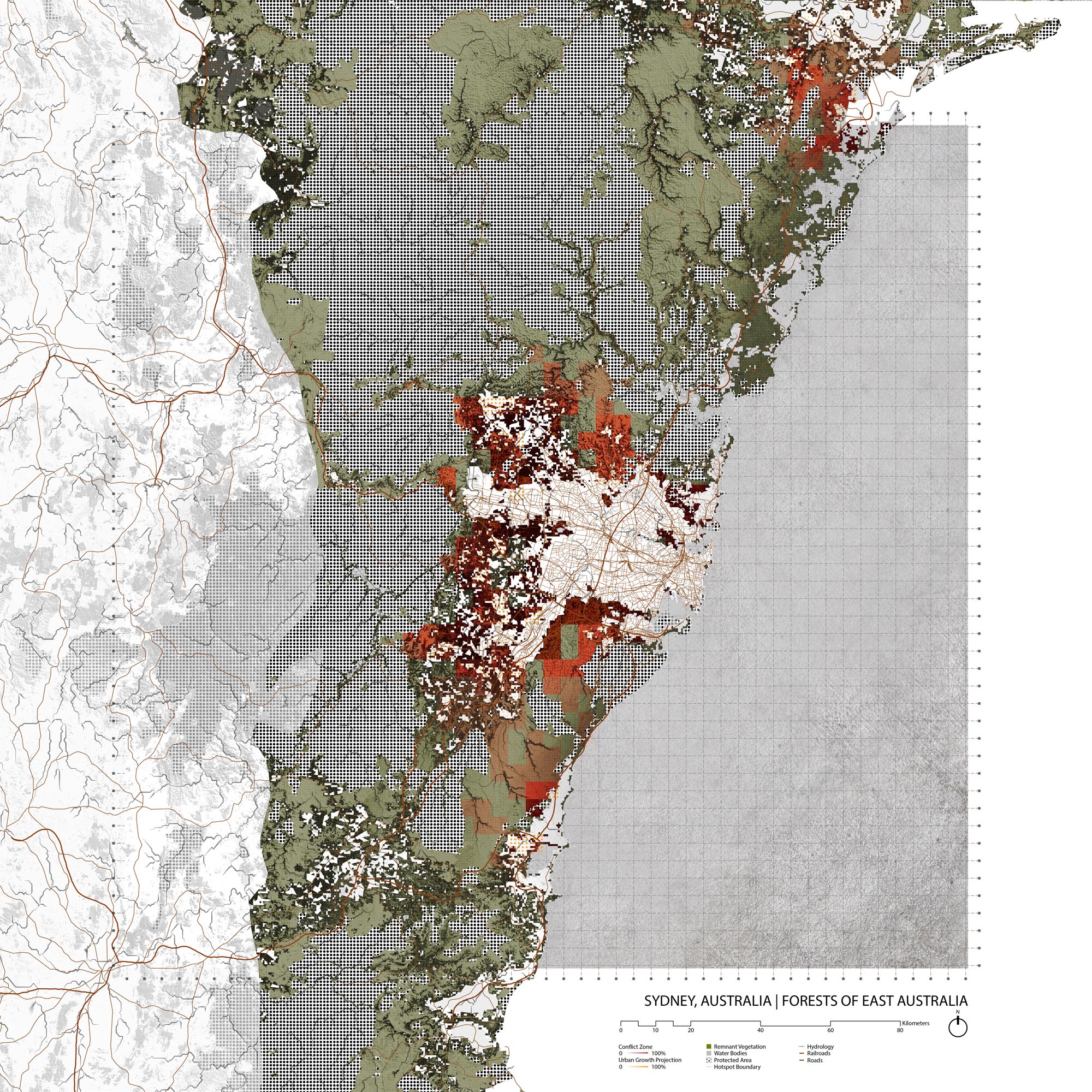

The Forests of East Australian was delineated as the 35 th biodiversity hotspot in 2011. It consists of a discontinuous coastal stretch along the states of Queensland and New South Wales , and includ es the New England Tablelands and the Great Dividing Range further inland. The hotspot contains a wide range of landscapes containing coastal plains, tropical rainforests, coastal and mountain range escarpments, elevated plateaus, and freshwater lagoons and lakes. The most prevalent vegetations are the s clerophyllous plant communities, dominated by the iconic Eucalyptus species . [2] Sclerophyllous species are mostly evergreen, scrub species with small, hard, thick, and leathery leaves adapted to survive hot, dry seasons of Mediterranean climates.

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage/Number of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

>8,250 |

>26% |

- Critically Endangered Wollemi pine ( Wollemia nobilis ), considered a living fossil |

|

Birds |

549 |

28 |

|

|

Reptiles |

DD |

27% |

|

|

Amphibians |

DD |

32% |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

>80 |

>10 |

|

The northern Queensland Tropical Rainforests Ecoregion in the north and the Eastern Australian Temperate Forests Ecoregion in the south—within which Sydney is embedded—face different primary threats . Whereas the northern rainforests are primarily threatened by invasive species (including Phytophthora caused dieback), habitat fragmentation through road and powerline construction, and pollution from agricultural runoff, the hi gher human population density areas of the south are primarily under pressure from ongoing clearing for development, altered fire regimes, water pollution (e.g. sewage disposal), hydraulic engineering, introduced species, and tourism. [4]

Eastern Australian Temperate Forests

The Eastern Australian Temperate Forests ecoregion extends from the central coast of the state of New South Wales, northward to the southeast of the state of Queensland, and inland to the Great Dividing Range . S ydney is located in the southern tip of the ecoregion. The climate in the Blue Mountains region near Sydney is warm-temperate, with rain concentrated in the summer . It b ecomes more humid moving east toward the coast. The region’s varied substrates, altitudinal gradients, and microclimates underpin the great diversity in vegetation communities. Temperate eucalypt forests dominate most of the region, though there are important rainforest communities in the Border Ranges and on sheltered, humid sites with rich soils. [5]

The ecoregion has two important centers of plant endemism and diversity – the sandstone cliffs around Sydney and the Border Ranges. The Blue Mountains Her itage Area, a reserve that protects some of the aforementioned sandstone cliffs, also support a high biodiversity. Many globally endangered birds inhabit this ecoregion; these contain the cr itically endangered regent honeyeater ( Xanthomyza phrygia ) and the en dangered eastern bristlebird ( Dasyornis brachypterus ). The venomous broad-headed snake ( Hoplocephalus bungaroides ) is restricted to the Hawkesbury sandstone formation found around Sydney. [6]

Once nicknamed the ‘Big Scrub’ because of its large expanses, the Australian rainforests have been reduced and fragmented over the centuries since European settlement . Sydney and Brisbane , both located in the Eastern Australian Temperate Forests , are two of Australia ’s largest population centers. G razing, logging, and urban expansion are associated with these populations . Exotic species, water pollution, and altered fire regimes also cause serious issues. Even though there are two World Heritage Sites in the ecoregion– the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves and the Greater Blue Mountains – th e se protected areas are impacted by heavy touris m , spread of weeds, and invasive animals. A n estimated 80,000 people reside in the Blue Mountains W orld H eritage S ite, along the bisecting Great Western Highway. [7] Presently, the Eastern Australian Temperate Forests are 18% protected and are at 7.51% terrestrial connectivity. [8]

Environmental History

The Sydney Basin is the site of Mesozoic sandstones and shales. The sedimentary rocks were laid by river sediments from the Late Permian to Mid Triassic. [9] The diverse geologic and biological landscape is a result of geographic isolation; first from colliding with Antarctica with no major land masses following, then from its separation from Gondwana and later Antarctica. [10]

The first human activity in the area now known as Sydney is possibly as early as 50,000 BP. Several distinct groups occupied the Sydney Basin , the largest of which were the people of the Dharug language group (also spelled Dharuk and Dharook). The landscape bears signs of being significantly by these groups, who relied on fish and shellfish from the sea as well as possum, vegetable roots, seeds, berries, mullet, eel, and kangaroo further inland. Aboriginal people sustained themselves with hunting, fishing, and gathering in the well-wooded area around the harbor. Their population at the time of the arrival of Europeans in 1788 is estimated to have been between 5000 and 8000. Violence and smallpox quickly decimated most of the indigenous people settled in the area. [11]

The First Fleet under the direction of Governor Arthur Phillip established a colony at Sydney Cove. Many of the early settlers were convicts transport to the colony. Port Jackson (now Sydney harbor) remained an important economic driver for the colony in the 19th century. In the 1820s, whale and seal hunting became a booming industry; as resources were decimated, the whaling ships moved onto New Zealand. Wool also became an important export industry, while local production of candles, sugar, flour, beer, pottery and bricks stimulated local growth. [12]

The suburbs to the south started to grew more quickly starting in the 1850s with the construction of railways, and continued with the building of tramways in the 1880s. Industry settled the land between Sydney harbour and Botany Bay to the south and east especially after legislation pushed industry out of the city. Urban development in the north and west was more gradual, transitioning first to grazing, orchards, and small farms. Recently, however, as Sydney’s population has exploded, development has been particularly rampant to the west, urbanizing long peri-urban zones. Today, Sydney is the largest city in Australia by both population and area. [13]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Today Sydney is a sprawling city anchored on the shores of Sydney Harbour but extending outward for more than 50 km, from the shores of the South Pacific Ocean in the east to the foothills of the Great Dividing Range in the west.

Deforestation, and by extension forest mismanagement, remains one of the most potent environmental dangers facing this ecoregion. The sprawl of Sydney and its suburbs have required land clearing for developments and agriculture to support the growing population. Fragmentation of forest systems exacerbate issues stemming from deforestation. [14]

The impact of deforestation is both broad and intense. Ecosystem damage endangers the different species inhabiting the area, including those listed as endemic and vulnerable. At least 10% of native Australian terrestrial species are endemic to this region. [15] Animals such as possums and gliders are among species affected, and the culturally significant koala bear is now considered functionally extinction because of deforestation and fragmentation. [16] Sediment pollution from soil erosion is also endangering the health of the Great Barrier Reef. Both deforestation and the subsequent land uses, such as livestock and crops, contribute to the sediment pollution. [17]

Mining is also a major threat to ecological health. The extraction of coal from the Sydney area has contributed to subsidence, wetland ecosystem disturbance, and water pollution. [18] These results directly damage both the species whose habitats are affected and humans, who have less clean water to drink.

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

In 2017, Sydney’s population grew by over 100,000 in a year for the first time. Overseas migration has contributed a majority of the region ’s population growth, accounting for over 80,000 people. [19] Areas in Sydney designated as “growth centres” by the NSW government saw population increase, while other areas saw decline. Since growth in Sydney is uneven, policies to revitalize underused land or increase density is required to avoid urban sprawl.

The type of growth in Sydney is largely formal.

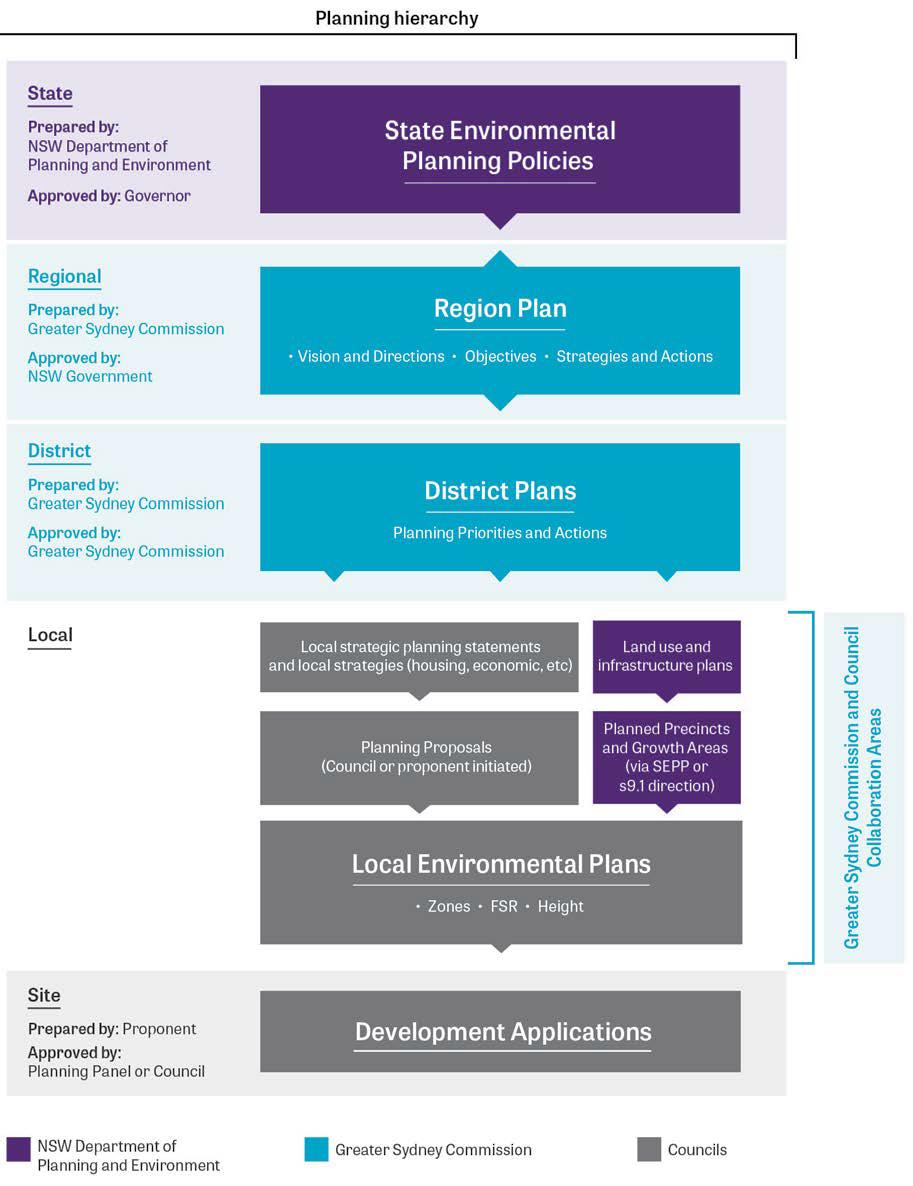

Governance

Australia is a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy with a second tier of government that encopasses six states and two inland territories. Sydney is the capital of the state of New South Wales. States are further divided in to local government areas, that are recognized by the constitutions of each of the states but not by the national constitution. These are generally called councils but names such as city, municipality, shire, and region are also given and have geographic interpretations. The Sydney metropolitan area overlaps with 31 local government areas. In 2015, the Greater Sydney Commission was created as an agency of the NSW government to plan the Greater Sydney Region with an integrated perspective on the metropolitan region as a whole. [20] The NSW government is in charge of major public infrastructure projects that influence growth in the region.

The 31 LGAs that overlap with the Sydney metropolitan area are: Bayside, Canterbury-Bankstown, Blacktown, Burwood, Camden, Campbelltown, Canada Bay, Cumberland, Fairfield, Georges River, Hawkesbury, The Hills, Hornsby, Hunter's Hill, Inner West, Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, Liverpool, Mosman, North Sydney, Northern Beaches, Parramatta, Penrith, Randwick, Ryde, Strathfield, Sutherland, Sydney, Waverley, Willoughby, and Woollahra.

City Policy/Planning

Planning Hierarchy for the Greater Sydney Area

Development Plan

The Greater Sydney Commission is an independent New South Wales agency that does integrated land use planning for the metropolitan area of Sydney, and has the authority to engage in large scale projects to benefit and connect the entire region under one vision. A Metropolis of Three Cities is the first regional plan developed by the commission and was developed in parallel with Future Transport 2056 and the State Infrastructure Strategy. [21] The plan uses economic development, infrastructure, transportation, and environmental planning to enhance livability, productivity, and sustainability for all residents of Greater Sydney. Many objectives for the plan address social needs, such as affordable and diverse housing, increased city connectivity, and increased economic activity. Energy, waste, and storm resilience goals address Climate Change directly. Rare for a growth plan, ecological needs also receive special attention, with the plan calling to protect biodiversity and green public space. Managing natural heritage sites, green networks, and unique ecosystems are specific plans to vitalize biodiversity in the region. Much of the plan’s ecological goals are expected to be a result of the collaboration with local governments, industry, developers, and the community.

The overall metropolitan regional planning process also led to the development of District Plans of a higher resolution.

Structure plan for the metropolis of three cities

The Urban Growth NSW Development Corporation is responsible for the economic development of five growth centres across metropolitan Sydney. They work with public and private actors to identify areas served by public transportation and infrastructure that can host housing and employment opportunities. They aim to create urban places with high environmental, social, and economic sustainability. The corporation’s goals for sustainability include making their projects carbon neutral, water positive, and zero-waste by 2028 and having all new projects either maintain or improve the biodiversity at a site. [22]

Local government areas develop other sectoral plans that influence environmental quality and biodiversity protection. For example, the City of Sydney adopted the Sustainable Sydney 2030 more than ten years ago and is currently in the processes of updating it with projections out to 2050. The City of Sydney also adopted the Environment Action 2016-2021 Strategy and Action Plan in 2017, which plans for the city to reduce its environmental impact and become resilience to the impacts from climate change. [23] The changes are directed towards meeting the standards set out in the Paris agreement to limit climate change to less than 2 degrees of warming. The plan emphasizes collaboration between government, private industry, and the community in order to successfully implement climate solutions. Focuses of the plan include greenhouse gas emissions, waste, drinking water, green space, and urban ecology. Specific goals include increasing reach of public transportation, expanding and connecting bike lanes, adding green spaces, recycling, flood management, and making buildings more energy efficient. The plan is a multi-pronged approach to make the City of Sydney thrive in the face of climate change.

Zoning

Zoning is developed at the local government level through Local Environment Plans delineate zoning for the types of development that can occur and where it is permitted, FSR (floor space ratio, aka FAR), and height restrictions. As these plans get redeveloped in the future, they are expected to align with both the overall Metropolitan Plan and the District Plans developed by the Greater Sydney Commission. [24]

As an example, the City of Sydney has not yet redeveloped its plan since the Greater Sydney Metropolitan Plan of the Greater Sydney Commission was adopted in 2018. It therefore uses the Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 as an instrument to ensure successful development. The plan aims, among other development goals, to promote ecologically sustainable development, conserve environmental heritage, and protect and enhance the enjoyment of the City of Sydney’s natural environment. The plan is a building and environmental code that specifies standards for development. Specific codes within the act restricts new structures if they’re in an area of declared biodiversity value, declared critical habitat, or wilderness area and must be of minimal environmental impact . [25]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Australia’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy 2010-2030 (NBSAP V2) is the result of a review of Australia’s 1996 National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia’s Biodiversity (NBSAP V1). [26] In 2006, the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council (NRMMC) established the National Biodiversity Strategy Review Task Group to review the 1996 strategy and other state, territory, and local strategies for biodiversity conservation. This strategy identifies three levels of biodiversity: genetic diversity, species diversity, and ecosystem diversity. Australia’s biodiversity is presented as something to appreciate both in its own right and for its contribution to human existence. Within the plan, there is a set of priorities for action to help achieve a diverse and resilient Australia. The first priority is to engage all Australians in biodiversity conservation, by mainstreaming, increasing Indigenous engagement, and enhancing strategic investments and partnerships. The second is building ecosystem resilience in a changing climate, to be achieved by protecting diversity, maintaining and re-establishing ecosystem functions, and reducing threats. The third priority is to get measurable results, through improving and sharing knowledge, delivering conservation initiatives efficiently, and implementing robust national monitoring, reporting, and evaluation. Australia established a national long-term monitoring and reporting system, the Natural Resource Management Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting and Improvement Framework (MERI). The plan also sets specific targets for increasing ecological health for both the ecosystem and human society. Collaboration across different levels of organization is highly valued, with market incentives mentioned as an essential tactic. Protection of biodiversity is considered a responsibility for all Australians. Although the plan identifies habitat loss as a significant threat to biodiversity, it does not explicitly mention urbanization as a threat. In 2015, NRMMC would have assessed the progress and suitability of the targets and determined subsequent schemes. [27]

National

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) delineates the Australian Government’s responsibilities for biodiversity conservation. It defines a legal framework to “protect and manage nationally and internationally important flora, fauna, ecological communities and heritage places,” including restricting development on World Heritage Sites, Ramsar wetlands, threatened species communities, water resources, and others. [28]

Regional

In 2016, NSW overhauled biodiversity efforts by passing the Biodiversity Conservation Act, which centralizes the process of biodiversity offsets and make it easier to clear land in accordance with certain codes. The act repealed and replaced the Native Vegetation Act 2003, Nature Conservation Trust Act 2001, Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, and sections of the National Parks & Wildlife Act 1974. [29] It streamlines the process for developers and resources project operators for biodiversity offsets through the newly established Biodiversity Conservation Trust and biobanking assessment methods. The act expands regulation and protection for threatened species and areas of outstanding biodiversity value that occurred under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995.

The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service commissioned a Biodiversity Planning Guide in order to assist local councils in facilitating biodiversity conservation. [30] The guide recognizes that certain types of knowledge and capacity for biodiversity planning can only be found in local governments, so creating the Biodiversity Planning Guide is a way to bridge the gap between state and local governments. From this guide, local governments and agencies to construct and implement biodiversity projects. Biodiversity is demonstrated as a common goal that must receive attention and action from all organization, ranging from local to international. The guide gives flexible and adaptable plans to allow local governments to compose a biodiversity strategy best suited for their particular ecological context. Case studies of local biodiversity projects are also provided, examples being habitat corridors and networks.

The Natural Resource Management (NRM) model is an integrated system of management of land, water, soil, plans and animals, and is collectively administered by 56 Natural Resource Management (NRM) regional organizations that include both government agencies and NGOs work on addressing natural resource issues at the landscape and regional scales. These scope of these NRMs together encompasses the management of the entire continent. Although they all have different histories and constitutions, they have all been recognized by the Federal Government as part of the National Landcare Programme (the most recent successor to the original Natural Heritage Trust program). This national program is primarily a funding stream established by the Australian Government to support NRMs. [31] The NRM responsible for metropolitan Sydney and its surroundings is the Greater Local Land Services Board. Where as the NRMs that coincide with the Perto metro region have explicit biodiversity agendas, the Greater Sydney NRM is more focused on agriculture and productivity. [32]

Local

An example of biodiversity planning at the local government area level is the City of Sydney’s Urban Ecology Strategic Action Plan , developed to support the Sydney Environmental Action 2016-2021 Strategy and Action Plan . [33] The goal of the plan is to retain and enhance urban biodiversity. The current biodiversity status in the City of Sydney was surveyed, noting flora and fauna that are critical to conservation efforts. From this survey, they identified priority sites, flora, and fauna with high biodiversity values. Five priority ecosystems and 8 priority threatened fauna were named. The strategic action plan’s objectives are to protect, expand, improve, and maintain the priority sites and species. Methods include improving site connectivity and increasing species distribution. The City of Sydney recognizes that urbanization has drastically changed the landscape, but recognizes that many indigenous flora and fauna still exist and should flourish.

Protected Areas

Sydney is surrounded by various national parks and nature reserves. The national parks are managed by the National Parks and Wildlife Service, an agency of the Department of Environment and Climate Change of NSW. North of Sydney, the largest protected areas area Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park and Marramarra National Park. Royal National Park and Dharawal National Park are the main protected areas south of Sydney, while Blue Mountains National Park sits west of the metropolitan area.

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

Great Eastern Ranges corridor, Cumberland Plain Recovery Plan, Linking Landscapes, NSW Green Corridors Program, Growth Centres Biodiversity Offset Program

The NSW government runs a repository for biodiversity data called BioNet. [34] The data is both publicly accessible and can be expanded by individual contributions of species sightings to the knowledge base. BioNet enables community, government, and other actors to manage and enhance biodiversity through comprehensive information.

Habitat Stepping Stones is an organization that allows individuals to add ecologically valuable habitats to their property . [35] Participants receive information on how to make their property more friendly to local wildlife. Elements to be added to backyards or balconies include food, water, and shelter. The idea is that animals can uses these places as “stepping stones” in their travel and increase connectivity. The initiative is aimed at rural and urban areas, which act as higher resistance areas for species movement .

The Centennial Parklands, which is under the authority of the Centennial Park and More Park Trust, is a collection of three parks within urban Sydney. [36] The Conservation Management Plan (CMP) works to ensure that the heritage and environmental significance is conserved for the future. [37] There are various policies to protect biodiversity, including vegetation management plans, tree master plans, and fauna master plans. CMP also calls for research into ecosystems functions like wetland formation and fauna movement.

[1] Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, “New South Wales,” http://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/research-topics/agricultural-commodities/australian-crop-report/new-south-wales (accessed July 2, 2018)

[2] CEPF. “Forests of East Australia.” Accessed May 31, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/forests-east-australia.

[3] CEPF. “Forests of East Australia - Species.” Accessed May 31, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/forests-east-australia/species.

[4] CEPF. “Forests of East Australia - Threats.” Accessed May 31, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/forests-east-australia/threats.

[5] WWF. “East Coast of Australia | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed May 31, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/aa0402.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Eastern Australian Temperate Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed May 31, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/10402.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Australia through Time, “Australia Separates from Antarctica,” http://austhrutime.com/separation.htm (accessed July 23, 2018)

[11] Heritage, corporateName=Office of Environment and. “Sydney Basin: Regional History-Aboriginal Occupation.” New South Wales Government: Office of Environment and Heritage. Accessed June 13, 2019. https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/bioregions/SydneyBasin-RegionalHistory.htm .

[12] Ibid.

[13] Heritage, corporateName=Office of Environment and. “Sydney Basin: Regional History-Aboriginal Occupation.” New South Wales Government: Office of Environment and Heritage. Accessed June 13, 2019. https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/bioregions/SydneyBasin-RegionalHistory.htm .

[14] WWF, “Deforestation in Eastern Australia,” http://wwf.panda.org/our_work/forests/deforestation_fronts/deforestation_in_eastern_australia/ (accessed July 2, 2018)

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid; WWF, “11 of the world’s most threatened forests,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/11-of-the-world-s-most-threatened-forests (accessed July 2, 2018)

[17] WWF, “Deforestation in Eastern Australia,” http://wwf.panda.org/our_work/forests/deforestation_fronts/deforestation_in_eastern_australia/ (accessed July 2, 2018)

[18] The Sydney Morning Herald, “New study finds significant impacts of coal mining in Sydney catchment,” https://www.smh.com.au/environment/grave-new-study-finds-significant-impacts-of-coal-mining-in-sydney-catchment-20170912-gyflz5.html (accessed July 2, 2018)

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, “Sydney population grows by over 100,000 in a year for the first time,” https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/sydney-population-grows-by-over-100-000-in-a-year-for-the-first-time-20180424-p4zbcj.html (accessed July 6, 2018)

[20] Legislation, “Greater Sydney Commission Act 2015,” https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/acts/2015-57.pdf (accessed July 2, 2018)

[21] “Greater Sydney Regional Plan: Metropolis of 3 Cities (A Vision to 2056).” Greater Sydney Commission, March 2018.

[22] UrbanGrowth NSW Development Corporation, “Climate, resilience & resources,” https://www.ugdc.nsw.gov.au/what-we-do/sustainability/climate-resilience-and-resources/ (accessed July 2, 2018)

[23] City of Sydney, “Environmental Action 2016-2021,” http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/284749/Environmental-Action-strategy-and-action-plan.pdf (accessed July 5 2018)

[24] “Greater Sydney Regional Plan: Metropolis of 3 Cities (A Vision to 2056).” Greater Sydney Commission, March 2018.

[25] Legislation, “Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012,” https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/~/pdf/view/EPI/2012/628/full (accessed July 3, 2018)

[26] Convention on Biological Diversity, “CBD Strategy and Action Plan - Australia,” https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/au/au-nbsap-v2-en.pdf (accessed July 6, 2018)

[27] Convention on Biological Diversity, “CBD Strategy and Action Plan - Australia,” https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/au/au-nbsap-v2-en.pdf (accessed July 6, 2018)

[28] “Department of the Environment and Energy.” Department of the Environment and Energy. http://www.environment.gov.au/ . Accessed May 21, 2019.

[29] Herbert Smith Freehills, “SWEEPING CHANGES PROPOSED TO NSW BIODIVERSITY AND NATIVE VEGETATION LEGISLATION,” https://www.herbertsmithfreehills.com/uk/grads/latest-thinking/sweeping-changes-proposed-to-nsw-biodiversity-and-native-vegetation-legislation (accessed July 6, 2018)

[30] Source missing...

[31] “NRM Regions Australia.” NRM Regions Australia. Accessed June 14, 2019. http://nrmregionsaustralia.com.au/ .

[32] “Biodiversity.” Greater Sydney Local Land Services. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://greatersydney.lls.nsw.gov.au/land-and-water/biodiversity .

[33] City of Sydney, “Urban Ecology Strategic Action,” http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/198821/2014-109885-Plan-Urban-Ecology-Strategic-Action-Plan_FINAL-_adopted.pdf (accessed july 3, 2018)

[34] Bionet, “NSW BioNet,” http://www.bionet.nsw.gov.au/ (accessed July 6, 2018)

[35] Habitat Stepping Stones, “About Us,” http://www.habitatsteppingstones.org.au/about (accessed July 6, 2018)

[36] Centennial Parklands, “Centennial Parklands,” http://www.centennialparklands.com.au/about/centennial_parklands (accessed July 6, 2018)

[37] Centennial Parklands, “Conservation Management Plan,” http://www.centennialparklands.com.au/about/planning/conservation_management_plan (accessed July 6, 2018)