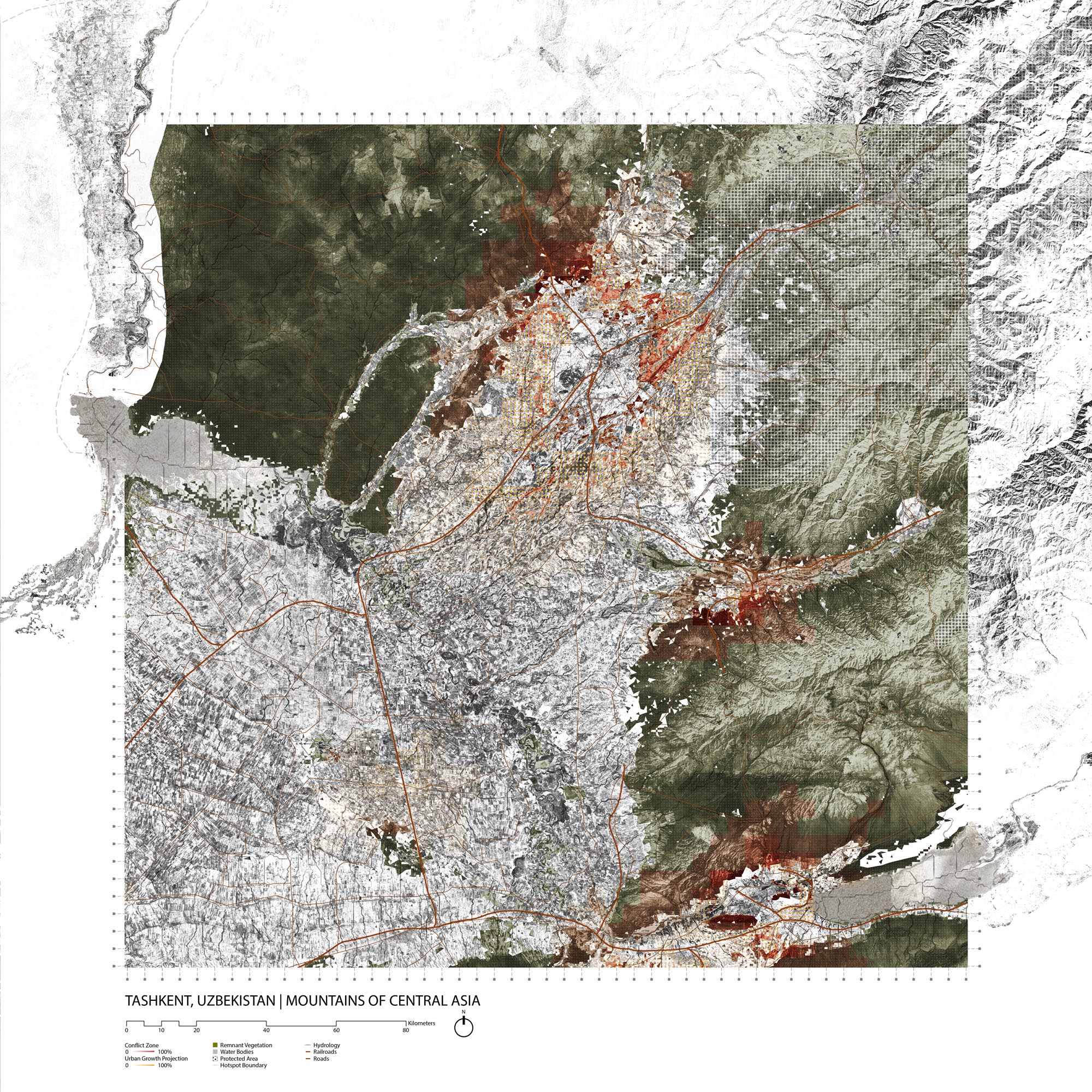

Tashkent, Uzbekistan

- Global Location plan: 41.30oN, 69.24oE [1]

- Hotspot: from google earth it appears to be around the border of Alai-Western Tian Shan Steppe and the Gissaro-Alai Open Woodlands

- Population 2015: 2,251,000

- Projected population 2030: 2,839,000

Endangered species

Amphibians

Mammals

- Meriones meridianus

- Rattus norvegicus

- Crocidura gmelini

- Meriones libycus

- Marmota caudata

- Marmota menzbieri

- Neodon juldaschi

- Tadarida teniotis

- Barbastella leucomelas

- Rhombomys opimus

- Ursus arctos

- Ochotona rutila

- Ursus arctos

- Felis silvestris

- Myotis emarginatus

- Sus scrofa

- Pipistrellus aladdin

- Myotis bucharensis

- Myotis bucharensis

- Rattus pyctoris

- Eptesicus bottae

- Myotis nipalensis

- Eptesicus gobiensis

- Panthera uncia

- Rhinolophus bocharicus

- Panthera uncia

- Nyctalus noctula

- Mus musculus

- Crocidura suaveolens

- Felis chaus

- Spermophilus fulvus

- Ursus arctos

- Ursus arctos

- Otocolobus manul

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Vulpes corsac

- Allactaga major

- Microtus gregalis

- Lutra lutra

- Lynx lynx

- Hypsugo savii

- Mustela eversmanii

- Myotis blythii

- Ellobius tancrei

- Crocidura serezkyensis

- Hystrix indica

- Allactaga elater

- Apodemus uralensis

- Meriones tamariscinus

- Vulpes vulpes

- Vormela peregusna

- Rhinolophus hipposideros

- Diplomesodon pulchellum

- Hemiechinus auritus

- Otocolobus manul

- Vespertilio murinus

- Capra sibirica

- Martes foina

- Dipus sagitta

- Dryomys nitedula

- Gazella subgutturosa

- Microtus ilaeus

- Pygeretmus pumilio

- Nesokia indica

- Meles leucurus

- Microtus socialis

- Allactaga vinogradovi

- Canis lupus

- Allactaga severtzovi

- Alticola argentatus

- Apodemus pallipes

- Cricetulus migratorius

- Blanfordimys bucharensis

- Spermophilopsis leptodactylus

- Mustela nivalis

- Lepus tolai

- Pipistrellus pipistrellus

- Lynx lynx

- Eptesicus serotinus

- Spermophilus relictus

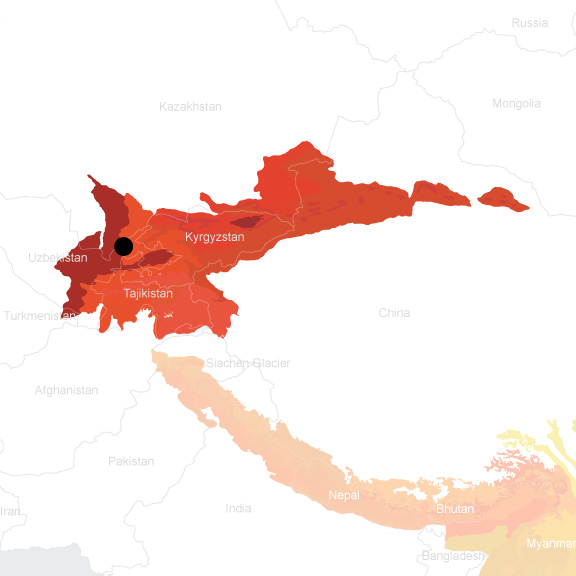

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

The Mountains of Central Asia Biodiversity Hotspot consists of two of Asia’s major mountain ranges, the Pamir and the Tien Shan. It has many mountains higher than 6,500 m and also large desert basins. Politically, the hotspot contains southern Kazakhstan, most of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, eastern Uzbekistan, western China, northeastern Afghanistan, and a small part of Turkmenistan. With the mixture of agrarian, nomadic, and industrial societies, it is a mosaic of languages, cultures, and political systems. [2]

Species statistics [3]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~5,000 |

~25% |

- significant numbers of wild crop relatives |

|

Birds |

DD |

DD |

- most migrate seasonally (latitudinally or altitudinally) |

|

Mammals |

~140 |

~10% |

- Vulnerable [4] snow leopard ( Panthera uncia ) - Vulnerable [5] Menzibier’s marmot ( Marmota menzbieri ) |

|

Reptiles |

>60 |

~25% |

|

|

Amphibians |

~10 |

~20% |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

30~60 |

~15% |

- endemism centered in the Issyk-Kul Lake and Talas River basin |

Habitat degradation in the hotspot mainly comes from modification of river flows and water withdrawal. Poor water management and irrigation practices led to salinization of soils, and overuse of fertilizers and pesticides caused pollution. Large areas of land have long been converted to agricultural use, mostly for cotton and cereal cultivation. Infrastructure, roadway construction, and urbanization also result in large-scale habitat loss. Other major threats to biodiversity include poaching, trophy-hunting, overgrazing, and human-wildlife conflicts.

[6]

CEPF’s future investment in the hotspot will focus on Key Biodiversity Areas that are in transborder areas.

[7]

Alai-Western Tian Shan Steppe

The city of Tashkent is located in the Alai-Western Tian Shan steppe ecoregion in central Asia. The Alai-Western Tian Shan Steppe ecoregion includes the vast foothill plains in western Tien Shan and Alai, as well as two massive mountains – Kara Tau and Nura Tau – and the Fergana Valley. The annual rainfall averages between 300 to 600 mm, and the average temperature is around 12 degrees Celsius. The climate allows for unique types of ephemeroidal herbaceous vegetation and the relic species. Thus, the region is characterized by a rich diversity of flora (over 2000 species) and high levels of endemism. The ecoregion has experienced a long history of intensive agricultural activity. Almost all suitable areas are plowed for crops, and the pasture grazing pressure is very high. Cotton cultivation on foothills and in the Fergana Valley is particularly intense. Such conditions lead to degradation of vegetation and even desertification in the region. All the while, fauna suffers from serious poaching issue. [8] At present, only 5 percent of the ecoregion is protected, and only 4.18 has terrestrial connections. Amongst the protected areas, Western Tien-shan (across Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan) has been designated as a World Heritage Site in 2016. [9]

Gissaro-Alai Open Woodlands

The North Eastern suburb of Tashkent is in the Gissaro-Alai open woodlands ecoregion.

The Gissaro-Alai Open Woodlands ecoregion is composed of the Gissar, Zerayshan, Turkestan, and Alai mountain ranges, stretching latitudinally for 900 km. The maximal elevation reaches 5500 m. The climate is continental, with precipitation at maximum in winter and spring, because of the Mediterranean and Atlantic air masses. The permanent glaciers of Gissaro-Alai feed a vast network of mountain rivers. Such conditions support a variety of landscapes ranging from foothill semi-deserts, alpine meadows to mountain forests. Characteristic vegetation includes coniferous evergreen Juniperus species, ephemeroidal herbs, unique fruits, and relict nuts. Common animals of the ecoregion contain wild boar, bear, ungulate, and birds of prey.

[10]

During the past two centuries, much of the natural woodland of the ecoregion have been cleared for firewood or overgrazed by the increasing amount of sheep, causing soil erosion. Other threats to biodiversity include forestry, building construction, and recreational activities.

[11]

Currently, 9 percent of the ecoregion is under protection, and 5.57 percent terrestrially connected. Amongst the protected areas, Ugam-Chatkal of Uzbekistan is the largest, a National Park near Tashkent.

[12]

Environmental History

Takshent may have been founded as early as 200BCE, and was a key point on the road of merchant caravanes, namely on the ancient silk road. The city was conquered by the Sunni Muslim Ummayad in the 8th century CE, explaining the Muslim majority in Uzbekistan. It was later invaded by the Mongols in the 13th century and later by the Sunni Timurids until the 16th century. The Central Asian Shaybānid dynasty ruled over Tashkent until the Khanate of Kokand took control of the area in the mid-1700s. When the city was captured by Russia in 1865, it became the capital of the governorate-general of Turkistan and a new European City sprouted asied the ancient one. It remained under Russian and later Soviet rule, until it became a Socialist Republic in 1924, and finally the Republic of Uzbekistan in 1991, with the fall of the USSR. [13]

Tashkent was struck by a major earthquake in 1966. The city was destroyed in many parts, sparking a debate on the direction of its reconstruction. Indeed, the disaster was an opportunity for Soviet authorities to modernize the city in their own terms, but it also made room for the design of american-inspired suburbs, or for a western-tinted movement of modernism. Reconstruction ultimately resulted in the destruction of a large part of the old city, to make way for larger streets and for soviet buildings which were later criticized for their their dissemblance to local styles. Many citizens were moved from individual houses to more compact apartment buildings. [14]

The result of Tashkent’s rich hisotory is a very ecclectic city plan, with some patches of structured, vertical developments surrounded by green areas, and others of extremely compact, winding neighborhoods with courtyards. The city is reputed to be safe and friendly, with a strong sense of tradition. [15] [16]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Although Tashkent has significantly decreased its air pollution levels over the past few decades, many efforts remain necessary to bring the city to a healthy standard. [17] In addition to air pollution, Tashkent is still recovering from a waste management crisis it faced with the fall of the Soviet Union, since the USSR controlled the city’s waste management system. A loan and project by the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has helped the city achieve relative success in developing a reliable waste disposal structure. [18] Water pollution caused mainly by industrial waste also constitutes a major problem for Uzbekistan in general; as of 2004, sewage in the country lagged significantly behind water supply. [19] Thus, pollution is a significant problem in the Tashkent area, and causes a significant threat to local biodiversity.

Soil erosion and salinization are creating a risk of desertification in the country, further threatening local ecosystems. These phenomena are caused by global warming and changes in precipitation patterns, as well as by certain agricultural practices, including over-grazing and intensive cotton monocultures. [20]

Indeed, cotton production was expanded greatly under soviet rule, and Uzbekistan came to become the world’s fourth largest producer of cotton in the mid-1990s. The country’s central government still controls agricultural land distribution, sets the prices for crops and imposes quotas on production. Although cotton is still the largest crop in the country, the state is trying to convert some fields for wheat culture. [21]

Cotton cultures are also the cause for significant human rights violations, namely forced labor and child labor. The central government forced children as young as 11 to labor fields until 2012. As of 2014, the state did not impose labor on a citizens younger than 17. However, certain local governments still force younger children to work to meet the challenging production quotas imposed by the country. [22]

Tashkent is situated in a plateau, southeast of the Kazakh border. Although some forest cover seems to remain in Kazakhstan, the plateau is completely covered in cultures on the Uzbek side of the border, leaving strictly no room for natural vegetation. Farmlands come to a stop where mountains rise to the east of Tashkent. Many rivers run through the city, including the Chirchik south-west of the city, the Salar Canal, the Budrjar, and the Bozsu canal. Tashkent has an effective transportation system, including a metro system and a high-speed train that connects to other central Asian cities.

Aside from a large cemetery and the city’s botanical gardens, the area within city borders is completely urban and quite dense. The urban fabric is a combination of tall apartment complexes surrounded by trees, built during the Soviet period, and of older, compact, irregular neighborhoods. The densification of Tashkent has caused the loss of the the traditional Uzbek courtyard in many houses. In recent years, the desire to return to a more traditional lifestyle has caused many citizens to construct suburban “dacha houses,” that allow them to maintain a garden. Thus, the dacha has emerged in a variety of styles as a Summer house for some and as a permanent home for others. [23]

Compact suburban settlements extend beyond the city borders onto rural areas. Historical imaging reveals that instead of spreading outwards before densifying, human developments were compact to start with and have expanded over the past thirty years in irregular patterns, especially along major transportation axes. Some of the most notable changes occured in the Kazakh portion of the city’s suburbs, which have grown to become urban areas themselves. [24]

WWII: strong economic dvpt, Tashkent became one of the largest centres of Soviet heavy industry (e.g. aviation and engineering), population then grew rapidly. [25]

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

The population in the formal urban settlements of Tashkent grew by 20% between 1985 and 2013, and the city’s density grew from nearly 998 to 1,320. In addition to this densification, the city is struggling to control its sprawl. Growth has occurred mainly through the increase of low-rise housing, but also through the development of apartment complexes. [26] The densest district of Tashkent is Shaykhontohur, which is mainly made up of old-city single-level homes, averaging a density of 10,500 hab/km2. [27]

Under the authoritarian rule of Islam Karimov, strict restrictions on rural populations made it difficult to migrate into the city, which somewhat limited the growth of informal settlements. [28] Since the ruler’s death in 2016, however, it is difficult to tell how much informal settlements are growing and exactly what portion of the city they currently occupy.

Governance

Uzbekistan is divided into 12 administrative regions. The Tashkent region, or “viloyat,” is further divided into 15 districts, including Tashkent City which has 11 districts of its own. [29]

Islam Karimov led an oppressive regime as the president of Uzbekistan from 1989 until his death in 2016. [30] After decades of disappearances, torture, and many other human rights violations, the dictator was replaced by the Russian Shavkat Mirziyoyev, whose election was likely rigged. [31]

City Policy/Planning

Development Plan

The 2030 Master Plan of Tashkent focuses on restructuring the current city and emphases the use of internal territorial resources in order to limit the city’s sprawl. Over a quarter of the city’s area is currently occupied by its streets, lawns, and parcs, yet the city does not currently include any conservation areas. The Master plan aims to create reserves in the city, and to limit the expansion of its industrial and residential areas. [32]

The Uzbek Committee on Architecture and Construction (Goskomarkhitektstroy) is responsible for elaborating a central planning scheme for the country which is used by regional (viloyat) and municipal (khokimiyats) governments. [33]

Thus far, the Tashkent was developed using functional zoning, in disregard of some of the city’s medieval neighborhoods, which were torn down during the soviet period. An article by Akhmedov and Nazarova suggests that older parts of the city should preserved and structurally understood to ensure the harmony of newer developments. The city, the conclude, should be planned plastically rather than functionally. [34]

In trying to open the city to foreign investors, Tashkent is trying to develop a business district, which is planned for in the masterplan designed by Haeahn Architects. Although the plan claims to be changing the natural and green systems of the city, the available renderings do not show any real concern for biodiversity conservation. [35]

The government is planning “Tashkent City,” a project for a new business district. In doing so, the government is tearing down many Mahallah districts--old, compact neighborhoods in Tashkent-- and displacing their inhabitants to the suburbs, where they can choose to live in an apartment or build a house on a lot of land to their own expense. [36]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

Although Uzbekistan is not one of the original signatories of the Convention on Biological Diversity, it acceded the agreement in 1995, and wrote a draft for its Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan by 1998. As of that year, protected areas in the country were small and poorly connected, covering as little as 2% of the country’s area. Additionally, awareness on biodiversity was extremely low, and the protected area system was deemed unsustainable given social and political conditions. [37]

The sixth national report of the Republic of Uzbekistan was released in 2018 [38] . The latest National Targets (responding to the AICHI Targets) - to be achieved by 2025 - include improving monitoring system, raising awareness, developing and implementing measures of sustainable use of ecosystems. [39]

National

The 2015 Fifth National Report on Conservation of Biodiversity provides a more recent description of the state of biodiversity in Uzbekistan. As of 2015, the Uzbekistan’s protected areas of IUCN categories I-IV covered 5% of the country’s area. In addition to this slight increase in protected areas, the state found some success in establishing sites for ex-situ conservation, and raising awareness. [40]

The document sets multiple priorities for conservation, including supporting and restoring ecosystems support to ensure ecosystem services, integrating biodiversity concerns into resource management, expanding protected areas and improving their management, and raising awareness. The report acknowledges multiple obstacles to biodiversity conservation, especially a lack of awareness and of funding, and poor coordination of conservation efforts. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of incorporating such efforts into existing legal frameworks.

The document also addresses the status of efforts that pertain to the Aichi objectives that the country set for 2020 and 2025. It describes targets and indicators for four strategic goals: mainstreaming biodiversity across the government and society, reducing direct pressure on biodiversity, developing the protected area system, and improving the effectiveness of conservation.

The existence of the Uzbekistan State Committee for Nature Protection shows some concern for conservation on a national level. [41] However, neither biodiversity conservation of urban expansion are not mentioned in any of the priority areas listed in the country’s Development Strategy for 2017-2021. [42]

Uzbekistan is a member to many international agreements and organizations related to conservation. In addition to the Convention on Biological Diversity, the country is a party to the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (1997), the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (1998), the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance(2002). [43]

Protected Areas Near City:

The Chaktal mountain-forest, is a 360km2 reserve of IUCN category I whose Charvak Lake is a major source of drinking water for Tashkent. [46] With an area of 5750km2, Umgal-Chaktal natural national park contains the Chatkalskiy State Nature Reserve, which was designated a UNEsCO biosphere reserve in 1978 and contributes to the protection of the Tien-Shan Mountains. [47]

In 2014, the state had plans to establish Durmen National Park, on an area of 32.4ha, in the Tashkent Region. [48]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The United Nations Development Programme is leading a project to “reduce competing land use pressures on natural resources of arid nonirrigated landscapes in Uzbekistan.” The project includes the improvement of 6,000ha of rangeland and 1,000ha of forest cover. The document also addresses the need for improvement in policies and institutions to allow for “integrated natural resource management.” [49]

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe organized a workshop in 2017 in cooperation with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and Uzbekistan's Committee of Forestry to develop criteria to assess the sustainability of forest management in the country. Additionally, the UN Development Account is providing the funds for a project on “Accountability Systems for Sustainable Forest Management in the Caucasus and Central Asia,” which is helping Uzbekistan fulfill its development targets. [50]

The Global Environment Facility also operated in Uzbekistan. The organization provides the funds necessary for developing countries to implement the Convention of Biological Diversity. [51] The GEF leads Small Grant Programmes (SGP) in Uzbekistan including the Tashkent Oblast Pistachio Reforestation Initiative. [52]

In addition to the presence of large intergovernmental organizations, smaller groups lead initiatives in Uzbekistan. For instance, the Uzbekistan Society or the Protection of Birds is an affiliate of Birdlife International which manages biodiversity data, namely through the Avis of Central Asia database (AviCA) to identify Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBA) in the country. [53] The Central Asian Biodiversity Network (CABNET) is a project by the Michael Succow Foundation which also seeks to improve biodiversity knowledge by supporting research and university partnerships.

Public Awareness

In many of its documents, Uzbekistan acknowledges the severe lack of biodiversity awareness in the country. Although Tashkent more specifically is one of the higher educated parts of the country, as little as 1.5% of schools in the city included the environment in their curriculum, as of 1998. [54]

In 2011, a seminar was held in Tashkent to educate a legislative deputies and environmental movement members as well as journalists. The focus of the seminar was to raise awareness with the Uzbek youth. [55]

The Ecological Movement of Uzbekistan was founded in 2008, and its main goal is to raise awareness and promote the involvement of the public in conservation efforts. [56]

Conclusion

Pollution and intensive agriculture constitute the biggest threats to Uzbek biodiversity today. More specifically, industrial waste, harmful extractive activities, overgrazing, and the expansion of agriculture are causing soil erosion, salinization and the desertification of ecosystems. The country has successfully expanded its protected area network and limited sprawl with its strict policies. However, its protected network remains too small. Additionally, data management for conservation seems quite rudimentary, and awareness in the country remains very low.

[2] CEPF. “Mountains of Central Asia.” Accessed August 9, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-central-asia.

[3] CEPF. “Mountains of Central Asia - Species.” Accessed August 9, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-central-asia/species.

[4] “Snow Leopard.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[5] “Menzbier’s Marmot.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

[6] CEPF. “Mountains of Central Asia - Threats.” Accessed August 9, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-central-asia/threats.

[7] CEPF. “Mountains of Central Asia.” Accessed August 9, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mountains-central-asia.

[8] WWF. “Central Asia: Kazahkstan, Uzbekistan, and into Tadjikistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 9, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0801.

[9] “Alai-Western Tian Shan Steppe.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 9, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/80801.

[10] WWF. “Central Asia: Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 9, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0808.

[11] WWF. “Central Asia: Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 9, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa0808.

[12] “Gissaro-Alai Open Woodlands.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 9, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/80808.

[13] Encyclopedia Britannica, “Tashkent,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Tashkent (accessed July 15, 2018).

Encyclopedia Britannica, “Uzbek khanate,” https://www.britannica.com/place/Uzbek-khanate (accessed July 15, 2018).

World History Encyclopedia Wiki, “Timurid Empire,” http://world-history-encyclopedia.wikia.com/wiki/Timurid_Empire (accessed July 15, 2018).

OrexCA, “Tashkent History,” https://orexca.com/tashkent_uzbekistan_history.shtml (accessed July 15, 2018).

[14] Nigel Raab, “The Tashkent Earthquake of 1966: The Advantages and Disadvantages of a Natural Tragedy,” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 62, 2, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43819634.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ac4529e0eb7d525ae0b17eba100081897

[15] Tom Bissell, Chasing the Sea: Lost Among the Ghosts of Empire in Central Asia (2007), ttps://books.google.com/books?id=D71ajuSFBpIC&pg=PT98&lpg=PT98&dq=slums+in+tashkent&source=bl&ots=BPrmIDc4I-&sig=qAcENIs6kalTF-1rhRk5HKkZcEk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjzlZ2G3JrcAhXITd8KHSaHBtQQ6AEITjAJ#v=onepage&q=slums%20in%20tashkent&f=false

[16] Anette Gangler et al., “Tashkent in Change - Transformation of the Urban Structure,”

[17] “Air pollution in Tashkent and other cities of Uzbekistan exceeds sanitary standards,” Uzbekistan National News Agency , February 2, 2018, http://uza.uz/en/politics/air-pollution-in-tashkent-and-other-cities-of-uzbekistan-exc-02-02-2018

UNECE, “Uzbekistan improves its air quality management, with help from UNECE,” https://www.unece.org/info/media/news/environment/2015/uzbekistan-improves-its-air-quality-management-with-help-from-unece/uzbekistan-improves-its-air-quality-management-with-help-from-unece.html (accessed July 15, 2018).

[18] The World Bank, “Project Performance Assessment Report, Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent Solid Waste Management Project,” June 9, 2008

[19] The United Nations, “Sanitation Country Profile, Uzbekistan,” http://www.un.org/esa/agenda21/natlinfo/countr/uzbek/sanitatuzb04f.pdf (accessed July 15, 2018)

[20] “Anti-desertification efforts to be mulled in Uzbekistan,” Azernews, April 11, 2013 https://www.azernews.az/analysis/52125.html

[21] FAO and Aquastat, “Irrigation in Central Asia in figures - AQUASTAT Survey, Uzbekistan,” 2012

[22] Cotton Campaign, “Uzbekistan's Forced Labor problem,” http://www.cottoncampaign.org/uzbekistans-forced-labor-problem.html (accessed July 15, 2018)

[23] EARTH

Hikoyat Salimova, “Post-Soviet Housing: “Dacha” Settlements in the Tashkent Region,” Critical Housing Analysis 3, 2

[24] EARTH

[25] https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/hlm/prgm/cph/countries/uzbekistan/07.cp.uzbekistan.2015.chap5.pdf

[26] https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/hlm/prgm/cph/countries/uzbekistan/07.cp.uzbekistan.2015.chap5.pdf

[27] Tashkent City Municipality, “Population,” http://tashkent.uz/eng/articles/7830/ (accessed July 15, 2018)

[28] Banyan, “There, nothing but order and beauty,” The Economist , June 18, 2010, https://www.economist.com/banyan/2010/06/18/there-nothing-but-order-and-beauty

[29] One Planet Nations Online, “Administrative Map of Uzbekistan,” http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/uzbekistan-administrative-map.htm (accessed July 16, 2018).

Картография (Cartography), “Тематические и справочные карты” (Thematic and Reference Maps), http://kartografiya.uz/ru/content/products/64/49 (accessed July 16, 2018)

[30] Mansur Mirovalev and Neil MacFarquhar, “Uzbeks Vote on Expected 4th Term for Authoritarian Leader,” New York Times (March 29, 2015), https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/30/world/asia/uzbeks-vote-on-expected-4th-term-for-authoritarian.html

[31] Ivan Nechepurenko, “In a Year of Election Upsets, Uzbekistan Delivers the Expected,” New York Times (December 5, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/05/world/asia/uzbekistan-election-president.html

C.J. Chivers, “An Uzbek Survivor of Torture Seeks to Fight it Tacitly,” New York Times (September 24, 2010) https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/25/world/europe/25umarov.html

[32] United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, “Country Profiles on Housing and Land Management,” 2015, 55-62

[33] United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, “Country Profiles on Housing and Land Management,” 2015, 55-62

[34] M.K. Akhmedov and D.A. Nazarova, “The ways of the Development of Architecture of Independant Uzbekistan,” International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research 4, 3 (March 2015).

[35] Haeahn, “Uzbekistan Tashkent Masterplan,” http://www.haeahn.com/en/project/detail.do?prjctUseSeq=21&addr=&prjctServiceSeq=&prjctListSeq=0&prjctSeq=437&searchKeyword=&searchCondition= (accessed July 16, 2018)

[36] Joanna Lillis, “Tashkent City: is 'progress' worth the price being paid in Uzbekistan?,” The Guardian (October 18, 2017), https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/oct/18/people-paying-tashkent-gentrification-mahallas

[37] The National Biodiversity Strategy Project Steering Committee with the Financial Assistance of The Global Environmental Facility and Technical Assistance of United Nations Development Programme, “Biodiversity Conservation National Strategy and Action Plan,” 1998,

https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/project_documents/Ntl%2520BD%2520Strategy%2520n%2520Action%2520Plan_4.htm

[38] THE SIXTH NATIONAL REPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN ON THE CONSERVATION OF BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. Pdf file. Accessed on August 16, 2019. https://www.cbd.int/doc/nr/nr-06/uz-nr-06-en.pdf

[39] Unit, Biosafety. “Uzbekistan - National Targets,” August 30, 2017. https://www.cbd.int/countries/targets/?country=uz .

[40] The National Biodiversity Strategy Project Steering Committee with the Financial Assistance of The Global Environmental Facility and Technical Assistance of United Nations Development Programme, “Biodiversity Conservation National Strategy and Action Plan,” 1998,

https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/project_documents/Ntl%2520BD%2520Strategy%2520n%2520Action%2520Plan_4.htm

[41] State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan for Nature Protection, “Home,” http://uznature.uz/en (accessed JUly 16, 2018)

[42] “Uzbekistan's Development Strategy for 2017-2021 has been adopted following public consultation,” Tashkent Times (February 8, 2017) http://tashkenttimes.uz/national/541-uzbekistan-s-development-strategy-for-2017-2021-has-been-adopted-following-

Taraqqiyot Strategiyasi Markazi (Development Strategy Center), “Ustuvor Yo’nalishlar” (Priorities), http://strategy.uz/ustuvor-yonalishlar (accessed July 16, 2018).

[43] UNDP Uzbekistan, “Celebration of the Biological Diversity Day” (May 22, 2014), http://www.uz.undp.org/content/uzbekistan/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2014/05/22/-elebration-of-the-biological-diversity-day-.html

[44] Ташкентское Областное Управление По Экологии И Охране Окружающей Среды (Tashkent Regional Department for Ecology and Environmental Protection), “Home,” http://tashvileco.uz/en/ (accessed July 16, 2018)

[45] Tashkent Municipality, “Ecology,” http://tashkent.uz/eng/articles/7935/ (accessed July 16, 2018).

Азима Киёсова, “По пути развития экологической сферы” (On the Way to the Development of the Ecological Sphere), Национальное информационное агентство Узбекистана (National News Agency of Uzbekistan) (September 9, 2015) http://uza.uz/ru/society/po-puti-razvitiya-ekologicheskoy-sfery-30-09-2015

[46] The National Biodiversity Strategy Project Steering Committee with the Financial Assistance of The Global Environmental Facility and Technical Assistance of United Nations Development Programme, “Biodiversity Conservation National Strategy and Action Plan,” 1998

Asia Adventures, “The Ugam-Chatkal National park,” http://www.centralasia-adventures.com/en/sights/ugam_chatkal_national_park.html (accessed July 16, 2018)

[47] The National Biodiversity Strategy Project Steering Committee with the Financial Assistance of The Global Environmental Facility and Technical Assistance of United Nations Development Programme, “Biodiversity Conservation National Strategy and Action Plan,” 1998

UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme, “Mount Chatkal,” http://www.unesco.org/mabdb/br/brdir/directory/biores.asp?code=UZB+01&mode=all (accessed July 16, 2018)

[48] “Uzbekistan to create national park Durmen” UzDaily (June 16, 2014), https://www.uzdaily.com/articles-id-28151.htm

[49] United Nations Development Programme, “Uzbekistan Project Document,”

[50] UNECE, “Visible progress in sustainable forest management and monitorig in Uzbekistan,” https://www.unece.org/info/media/news/forestry-and-timber/2017/visible-progress-in-sustainable-forest-management-and-monitoring-in-uzbekistan/doc.html (accessed July 16, 2018).

UNECE, “Accountability Systems for Sustainable Forest Management in the Caucasus and Central Asia” http://www.unece.org/forests/areas-of-work/capacity-building/unda2016-2019.html (accessed July 16, 2018).

[51] Global Environment Facility, “Uzbekistan,” https://www.thegef.org/country/uzbekistan (accessed July 16, 2018).

Global Environment Facility, “Biodiversity,” https://www.thegef.org/topics/biodiversity (accessed July 16, 2018).

[52] The GEF Small Grants Programme, “Tashkent Oblast Pistachio Reforestation Initiative (TOPRI),” https://sgp.undp.org/index.php?option=com_sgpprojects&view=projectdetail&id=24055&Itemid=272 (accessed July 16, 2018).

[53] “Uzbekistan – Uzbekistan Society for the Protection of Birds (UzSPB),” https://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/partners/uzbekistan-%E2%80%93-uzbekistan-society-protection-birds-uzspb (accessed July 2018)

Uzbekistan Society for the Protection of Birds “Mission of UzSPB,” http://www.uzspb.uz/uzspb_mission.html (accessed July 16, 2018)

Uzbekistan Society for the Protection of Birds “IBA Program,” http://www.uzspb.uz/iba_prog.html (accessed July 16, 2018)

Uzbekistan Society for the Protection of Birds “AviCA,” http://www.uzspb.uz/avica.html (accessed July 16, 2018)

[54] The National Biodiversity Strategy Project Steering Committee with the Financial Assistance of The Global Environmental Facility and Technical Assistance of United Nations Development Programme, “Biodiversity Conservation National Strategy and Action Plan,” 1998

[55] Nazokat Usmanova, “Environemntal Issues Discussed in Tashkent,” Uzbekistan National News Agency (April 28, 2011), http://uza.uz/en/programs/25-years/environmental-issues-discussed-in-tashkent-28.04.2011-1897/

[56] “Environmental Movement set up in Uzbekistan,” Uzbekistan National News Agency (April 28, 2011), http://uza.uz/en/society/environmental-movement-set-up-in-uzbekistan-05.08.2008-367