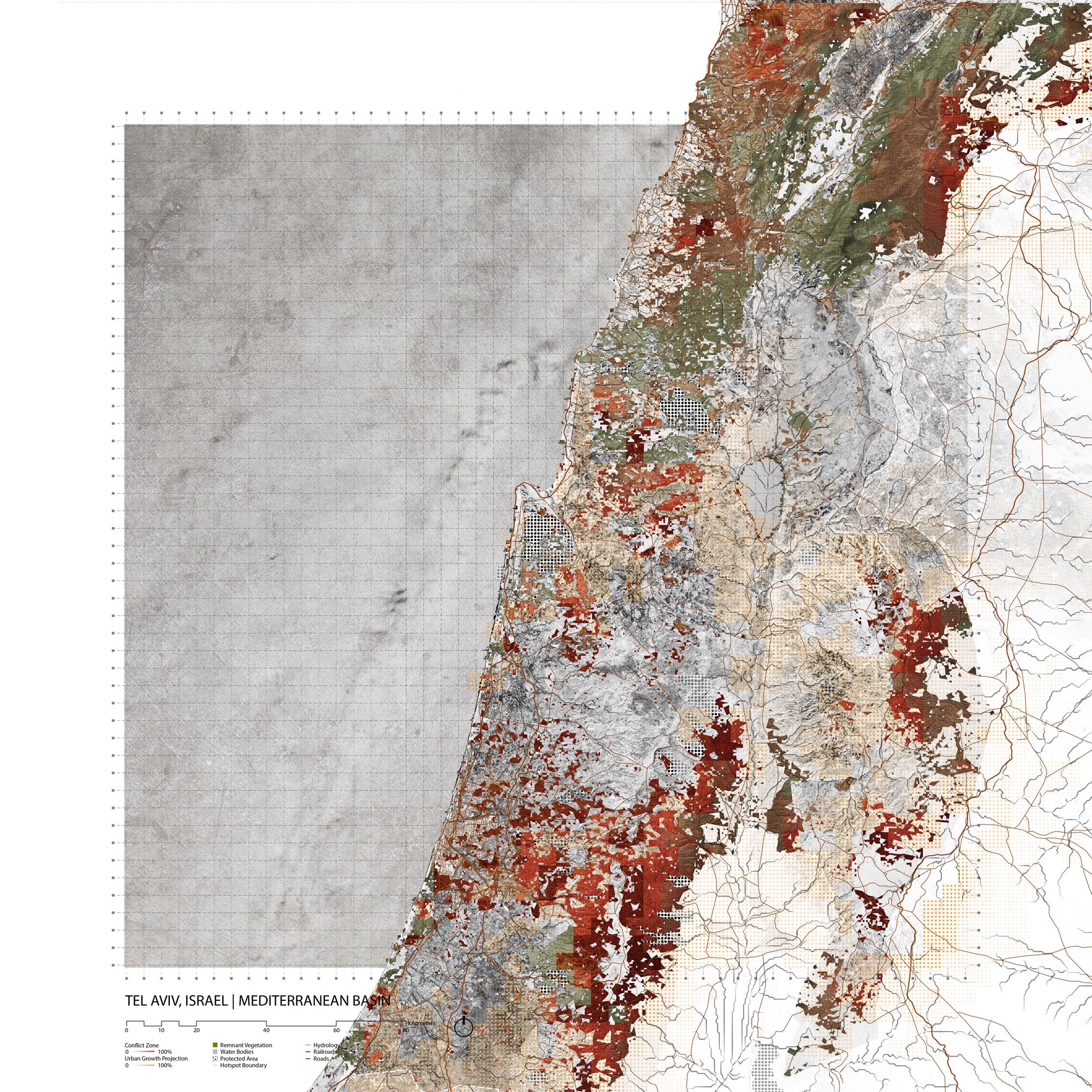

Tel Aviv, Israel

- Global Location plan: 32.09oN, 34.78oE [1]

- Ecoregion: Eastern Mediterranean Conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf Forests (needs 35,678km2)

- Population 2015: 3,608,000

- Projected population 2030: 4,382,000

- Endangered species: loggerhead marine turtle, euphrates softshell turtle

- Mascot Species: bald ibis (critically endangered), Mediterranean monk seal, loggerhead marine turtle, Euphrates softshell turtle, imperial eagle[2]

- Primary Crops: wheat, barley, seed cotton, almond, grapes[3]

Endangered species

Amphibians

- Bufotes variabilis

- Bufo bufo

- Ommatotriton vittatus

- Ommatotriton vittatus

- Pelophylax bedriagae

- Latonia nigriventer

- Latonia nigriventer

- Hyla savignyi

- Pelobates syriacus

- Pelobates syriacus

- Salamandra infraimmaculata

- Salamandra infraimmaculata

- Bufotes boulengeri

- Bufotes variabilis

Mammals

- Microtus guentheri

- Rattus norvegicus

- Otonycteris hemprichii

- Meriones crassus

- Meriones crassus

- Meriones libycus

- Tadarida teniotis

- Rhinolophus blasii

- Rhinolophus ferrumequinum

- Pseudorca crassidens

- Rhinolophus euryale

- Rhinopoma microphyllum

- Rhinolophus clivosus

- Herpestes ichneumon

- Ursus arctos

- Mellivora capensis

- Ursus arctos

- Capreolus capreolus

- Eliomys melanurus

- Rhinolophus mehelyi

- Gazella gazella

- Felis silvestris

- Plecotus macrobullaris

- Apodemus witherbyi

- Crocidura katinka

- Crocidura ramona

- Myotis emarginatus

- Sus scrofa

- Tursiops truncatus

- Asellia tridens

- Rattus rattus

- Eptesicus bottae

- Gerbillus andersoni

- Plecotus kolombatovici

- Nycteris thebaica

- Taphozous nudiventris

- Dugong dugon

- Allactaga euphratica

- Panthera pardus

- Physeter macrocephalus

- Panthera pardus

- Calomyscus tsolovi

- Meriones sacramenti

- Gazella gazella

- Erinaceus concolor

- Nyctalus noctula

- Mus musculus

- Suncus etruscus

- Crocidura suaveolens

- Grampus griseus

- Caracal caracal

- Rousettus aegyptiacus

- Felis chaus

- Gerbillus gerbillus

- Gerbillus henleyi

- Jaculus jaculus

- Asellia tridens

- Gerbillus cheesmani

- Orcinus orca

- Pipistrellus kuhlii

- Meriones tristrami

- Miniopterus schreibersii

- Sciurus anomalus

- Mus macedonicus

- Gazella dorcas

- Jaculus orientalis

- Lutra lutra

- Paraechinus aethiopicus

- Pipistrellus ariel

- Hypsugo savii

- Meles meles

- Myotis blythii

- Acomys dimidiatus

- Hystrix indica

- Stenella coeruleoalba

- Steno bredanensis

- Chionomys nivalis

- Ziphius cavirostris

- Vulpes vulpes

- Lepus capensis

- Vulpes rueppellii

- Vormela peregusna

- Rhinolophus hipposideros

- Taphozous perforatus

- Procavia capensis

- Hemiechinus auritus

- Delphinus delphis

- Acomys russatus

- Capra nubiana

- Rhinopoma hardwickii

- Vulpes cana

- Crocidura leucodon

- Martes foina

- Apodemus flavicollis

- Arvicola amphibius

- Myotis myotis

- Dryomys nitedula

- Gerbillus dasyurus

- Hyaena hyaena

- Psammomys obesus

- Myotis capaccinii

- Nannospalax ehrenbergi

- Nesokia indica

- Nycteris thebaica

- Microtus socialis

- Canis lupus

- Apodemus mystacinus

- Capra nubiana

- Balaenoptera physalus

- Cricetulus migratorius

- Mustela nivalis

- Pipistrellus pipistrellus

- Myotis nattereri

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Eptesicus serotinus

Hotspot & Ecoregion Status

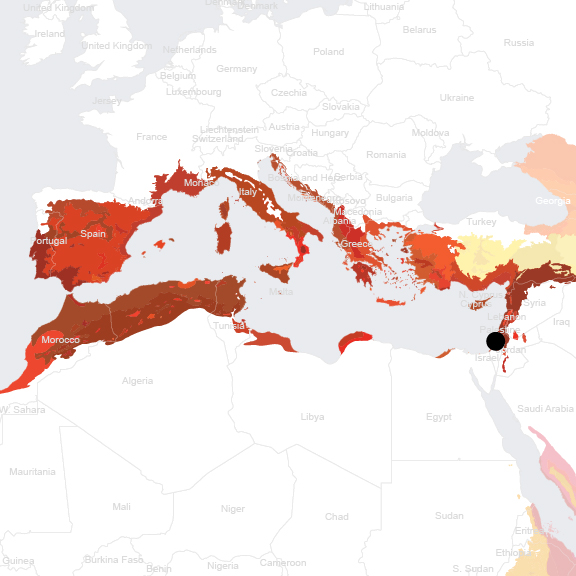

The Mediterranean Basin stretches from Cabo Verde in the west to Jordan and Turkey in the east, and from Italy in the north to Tunisia in the south. It also includes some 5,000 islands scattered around the Mediterranean Sea and several Atlantic islands. [4] The hotspot contains four biomes: Mediterranean forests, woodlands and scrubs; montane grasslands and shrublands; temperate broadleaf and mixed forests; temperate conifer forests; and tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests. [5] Rivaling the natural richness in the hotspot is its cultural, linguistic, and socio-economic diversity. It is the second largest hotspot and covers 22 countries. [6] Eight thousand years of human settlement has significantly altered the original habitat and vegetation. [7]

Species statistics [8]

|

|

Number of species |

Percentage of endemics |

Notable species / Additional info |

|

Plants |

~25,000 |

DD |

- the third richest hotspot in the world in plant diversity - high concentration on islands – true, “edaphic”, and “topographical” |

|

Birds |

534 |

~12% |

- three main groups/origins: northern, boreal; steppe; shrubland - many migratory flyways |

|

Mammals |

~300 |

~13% |

- mostly small species; rodents and shrews are the most numerous |

|

Reptiles |

~300 |

~40% |

|

|

Amphibians |

109 |

~50% |

|

|

Freshwater Fishes |

DD |

DD |

- the hotspot contains 26 freshwater ecoregions - particularly high level of endemism in Balkans and Turkey |

|

Invertebrates |

Estimated at 150,000 |

DD |

- dung beetles, butterflies, dragonflies |

The Mediterranean Basin hotspot is home to about 515 million inhabitants, 33 percent of whom live on the coasts. Adding on average 220 million tourists a year, the region experiences one of the heaviest human pressures on earth and has the lowest percentage of remaining natural vegetation – less than 5 percent. [9] The IPCC identifies this region as one of the most vulnerable hotspots in the world, in large part due its rising temperatures, declining annual rainfall and sea level rise, all of which deeply impact biodiversity throughout the region. [10] Major threats to biodiversity in the hotspot include dam construction (menacing 32 percent of freshwater fishes), forest fires (intensified by Climate Change), pollution (urban sewage, pesticide, nutrient additives, heavy metals, oils, toxic chemicals, solid waste), transport infrastructure, and tourism. In terms of agriculture, both intensification in some areas and the abandonment of farmlands in some other lead to the landscape’s degradation. [11]

CEPF awarded in total US$11.2 million of grants to 84 different organizations in 12 countries in the hotspot, from 2012 to 2017. During this first phase of investment, the funds tackled conservation issues at the local level. The current, second phase, with US$10 million from 2017 to 2022, CEPF will focus on protecting plants, promoting regional networks, and preserving three specific ecosystems – coastal, freshwater, and traditionally managed landscapes. Site-based conservation action is a priority. [12] While Mediterranean Basin has exceeded the 17 percent AICHI target, and Israel as a whole has also done important work to expand their forest coverage, the municipality of Tel Aviv remains well below this benchmark in its own biodiversity conservation efforts. [13]

Eastern Mediterranean Conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf Forest

Tel Aviv, and Israel more broadly, is located within the Eastern Mediterranean Conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf Forest ecoregion. [14] The Eastern Mediterranean Conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf Forests ecoregion lies along the Mediterranean coasts of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Palestine, and in the nearby coastal plains and lowlands. Major avian migratory routes from Africa to the north pass through this area, making it an area of high bird diversity. The climate is characterized by warm, rainy winters and dry, hot summers. [15]

The ecoregion has three main components: 1. The southern Mediterranean coast of Anatolia. 2. Southeastern Anatolia and the Northern Syrian basin. 3. Syrian, Lebanese, Israeli and Jordanian plains excluding the Levantine mountains. Vegetation can also be organized into three main groups: 1. Broadleaf sclerophyllous vegetation (maquis). 2. Coniferous forests of Aleppo pine ( Pinus halepensis ) and Callabrian pine ( Pinus brutia ). 3. Dry oak ( Quercus spp .) woodlands and steppe formations. The ecoregion is famed for its nature-based Mediterranean civilizations. Many plant species are important components of the local human cultures. [16] For instance, Israel has one of the world’s largest collections of wild wheat, barley, oat, and legumes, and a rich variety of fruits and other crops. It is an important area for agro-pastoral systems. [17]

Due to the long history of heavy human settlement, this ecoregion is among the most degraded areas in the world. Major threats consist of agriculture (overuse of insecticides and fertilizers included), tourism, anthropogenic fires, and intensive grazing. [18] Presently, only 1 percent of the ecoregion is protected, and only 0.33 percent has terrestrial connection. [19]

Environmental History

Modern day Israel is only 60 years old yet the environmental and geographical history of this region extends back to the BC era. While Israel was established as a Jewish State by the UN Partition Plan of 1947, the southernmost section of Tel Aviv-Yafo first surfaced from the ancient port city (Jaffa) of Egypt in the Bronze Age. [20] In 1910, a group of affluent Jewish merchants fled Jaffa’s growing congestion toward the desert lands just north of the ancient Arab port city. The merchants there created a new homestead society: Tel Aviv. [21]

Through the early twentieth century, the marginal Jewish suburb of Tel Aviv expanded as more Jews fled escalating religious tensions in Jaffa. [22] Simultaneously, intensifying anti-Semitic sentiment in Europe drove Jewish migration to the region. Many of these Jewish migrants sought refuge in Tel Aviv. Before long, the suburb’s population growth outpaced that of its southern Arab counterpart. [23] In 1921, Tel Aviv gained official township status, and in 1925, the Zionist Committee of Palestine commissioned the renowned urban environmentalist/planner Patrick Geddes to develop Tel Aviv’s first Master Plan. Geddes’ Garden City plan for Tel Aviv aimed to recreate this ideal arcadian setting within Tel Aviv’s dynamic urban center through semi-detached housing, private yards and ecological corridors. [24] In effect, the plan transitioned the township into a city that emulated Jewish Zionism and the age-old concept of ‘Agricultural Palestine.’ [25]

In addition to a deep cultural commitment to nature conservation as a form of agricultural preservation , some environmental activists in Israel also promote nature conservation purely for the purposes of preventing environmental degradation and protecting wildlife habitat. This strain of environmentalism that recognizes the value of nature on its own terms began in the 1950s as reaction to proposals to drain Lake Hulah:

“The roots of Israel's nature protection movement may be traced back to the organization of a small group of nature lovers and scientists around a specific issue: the draining of Lake Hulah and its surrounding swamps in order to combat malaria and reclaim the land for agriculture (1951-58). This small group of conservationists, who fought for the preservation of a small area of swampland as a nature reserve, understood that the death of the swamps would spell the death of the valley's indigenous flora and fauna as well. Their successful campaign assured not only the survival of the Hulah habitat, but the birth of Israel's nature protection movement.” [26]

An influx of European refugees in the latter half of the twentieth century [27] created an overwhelming need for housing that led the city to abandon certain aspects of Geddes’ Master Plan in favor of vertical and horizontal density, [28] accelerating the trend of this city’s outward expansion and the consequential destruction of surrounding biodiversity. [29]

Current Environmental Status & Major Challenges

Centuries ago, before urbanization occurred at such a rapid pace, hunting and agriculture were the main threats to this region’s biodiversity. Today, hunting has been replaced by the destruction and fragmentation of habitats, the introduction of invasive species, and the overexploitation of natural resources, all of which link back to unmanaged urban growth. [30] The IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation similarly identifies rapid urbanization of coastal zones and reduced extent of natural areas as the two main environmental problems of the Mediterranean region. [31] In response, the Centre’s 2017-2020 Mediterranean Program hopes to accelerate implementation of existing plans aiming to slow the rate of habitat and species loss. [32]

Adding to the negative impacts of urbanization in the Mediterranean Basin, more than 1,000 invasive species have been identified in this hotspot, 60 percent of which pose threats to endemic biodiversity conservation. [33]

Climate change also seriously threatens biodiversity conservation in the Mediterranean Basin. In Israel specifically, climate change is surfacing in the form of: “the ongoing deterioration of freshwater habitats, the decline of shrubland and woodland areas, and increased frequency and severity of forest fires.” [34] These consequences are primarily a result of (1) reduced total rainfall, which in turn causes plant desiccation and mortality; (2) increased frequency and intensity of droughts, which increases fire risks thus changing the structure of plant ecosystems; and (3) rising temperatures, which impacts bird migratory routes. [35]

Indigenous forests in present-day Israel were nearly totally destroyed by the early 20th century due to centuries of continuous grazing. Recent tree planting and reforestation efforts, however, have been relatively successful . [36] Between 2001-2012, Israel increased its total forest coverage. Notably, this success has occurred despite losses in urban tree canopy within Tel Aviv: between 2001 and 2017, the city lost just over 2ha of tree cover . [37]

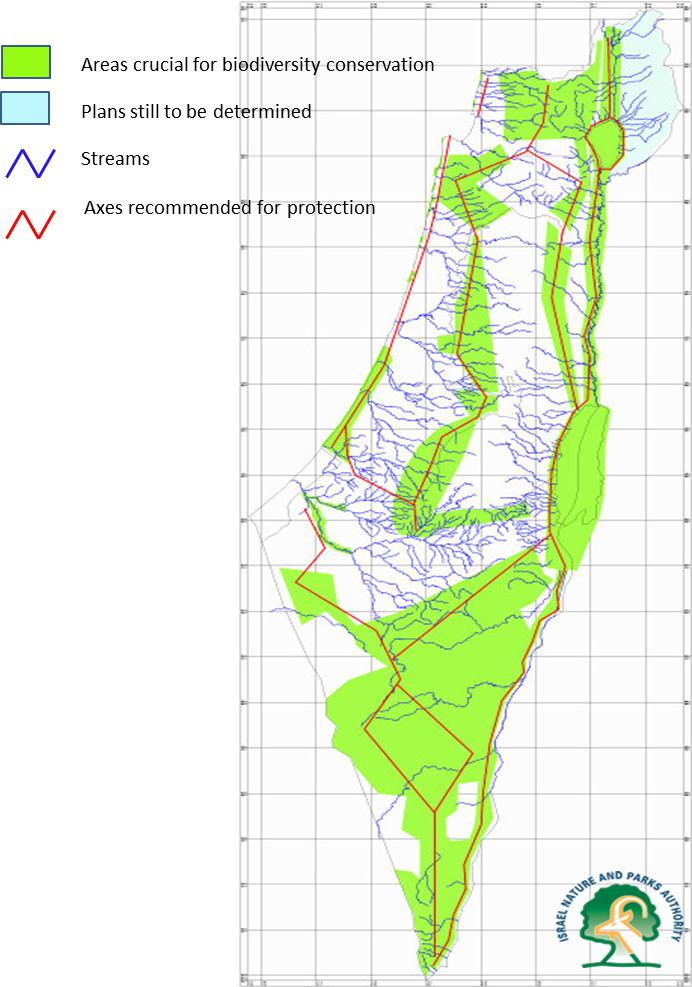

T he main problem facing nature conservation throughout Israel is still habitat fragmentation. Despite its 105 declared nature reserves located throughout 250 km2, most of Israel’s wildlife still lives outside nature reserves. The current momentum of urban development positions nature reserves as the last chance for many species to survive. At the same time, the small size of most reserves (63 percent are smaller than 1 km2 and another 25 percent are smaller than 10 km2) makes them vulnerable to the impacts of their rapidly urbanizing surroundings. Thus, the future of this area’s flora, fauna and ecosystems, both within and beyond the nature reserves, remain at risk. [38]

Zooming into Tel Aviv, threats to biodiversity at the municipality level include transportation infrastructure, urban development, agricultural intensification, climate change, water management, hydro-powered dams, pollution, poaching and tourism. [39] Of these, as previously discussed, the most serious threat is the city’s accelerated rate of developme nt and population growth. [40]

Growth Projections + Type of Growth

Tel Aviv-Yafo has over three million residents and is continuing to grow. [41] Between 2000 and 2014, the city experienced a population growth rate of 2.5 percent (compared to a global urbanization rate of 2.8 percent). [42] One way the city has managed its growth is by decreasing the built-up area density and urban extent density while increasing absolute urban extent. [43] The city manages to do this without sprawl through the adopted Dutch model of ‘concentrated dispersal.’ [44] Essentially, this means that Tel Aviv-Yafo decentralizes its population and economic resources into a selection of multiple urban nodes, each of which remains connected to the city center. This model lends to future population growth and land development forecasts being concentrated in the city’s outer ring.

Tel Aviv-Yafo has also accommodated ongoing growth through a model of state-sponsored gentrification, primarily targeting Jaffa, the municipality’s ancient southern port city. [45] The New Planning Doctrine of the 1990s had called for increased building density (read: modern skyscrapers) to replace the Jaffa’s old-world architecture and preexisting low density single-family dwellings. [46]

As since long before Israel’s founding, Tel Aviv’s growth largely remains a function of Jewish immigration. [47] According to the last report from WWF on Mediterranean trends, the population of [ which area ] is expected to grow by 5 percent from 2010 to 2030, reaching more than 580.000 in the next two decades. [48]

Earlier in the 2000s Tel Aviv experienced an influx of African refugees mainly from Eritrea and Sudan. The inflow has since stopped and the city’s African population has even begun reversing due to controversial deportations. Today, Tel Aviv is home to more than 40,000 African asylum seekers. Israel has so far refused to grant citizenship or refugee status to these asylum seekers. The government intentionally centralizes this immigrant population within the informal communities of South Tel Aviv. [49] Whereas Israel previously kept a portion of these refugee camps in detainment centers outside of Tel Aviv, those have been disbanded and Israel has more recently begun deporting a portion of its single, male refugees to other African countries, including Rwanda . [50]

Governance

Israel is divided into regions where local authorities govern matters of education, culture, social welfare, health, road maintenance, public parks, water and sanitation according to bylaws approved by Israel’s Ministry of Interior. Public financing is provided from local taxes and national budget allocations. Governing local bodies are categorized as municipalities (73), local councils (124) or regional councils (54) depending on the respective region’s population. Tel Aviv-Yafo is the second largest of the nation’s 73 municipalities and is governed by a mayor and city council. All municipalities and local councils are jointly represented by one central body, the Union of Local Authorities. [51]

In Tel Aviv, secret ballot elections for mayor and council take place every five years. The mayor is chosen by a direct vote whereas council members are chosen by party vote. Tel Aviv is currently headed by Mayor Ron Huldai who is serving his fourth consecutive term. [52] Tel Aviv was founded in 1909 and united with Jaffa in 1950, at the time of Israel’s founding, into one municipality (52km2): Tel Aviv-Yafo. [53]

City Policy/Planning

Ninety percent of Israel’s land is owned by the state. Therefore, the state decides when and how much land to lease to kibbutzim, moshavim and private corporations. Planning and land use decision-making is determined by a handful of political institutions, namely the following three committees: (1) Planning Administration at the Ministry of Interior, which consists of politicians and one professional planner, to direct urban policy at the national and district level; (2) Israel’s Land Administration (ILA), which oversees use of public land; and (3) Ministry of Housing, which annually determines new residential demand across the country. [55]

The Ministry of Interior appoints local planning committees to oversee regional planning, permitting and zoning enforcement. Local planning committees “can block quite effectively undesired plans and initiate plans.” [56] Furthermore, by way of Israel’s “nonconforming use” policy, these committees can sidestep superior departments in their effort to rezone land, a strategy typically employed for purposes of rezoning agricultural land for commercial development. [57]

The 1992 system of compensation known as betterment levies rewards the ILA for upzoning agricultural land yields waves of large scale agricultural rezoning, as what took place in the 1990s, and a broad culture of pro-development land use planners. [58] Under the betterment levies policy, 50 percent of a rezoned parcel’s increased property value is paid to the ILA. Furthermore, in most cases, the Israeli economic system views industry and residential development as higher and better uses than farmland. For a brief period, betterment levies were divided between the original lessees of rezoned land and the IRA. During this period, kibbutzim, the historic “watchdogs of Israel’s agricultural land,” eagerly returned their land to the government for real estate profit. [59] Decision 611 (1994) revoked profit sharing on rezoned land and in 2002, the High Court reinstated but significantly reduced compensation for original lessees on rezoned land. [60]

As the concentrated dispersal growth model advances outer ring development, business taxes propel the revenue potential of Tel Aviv suburban councils. In turn, suburban councils pressure city agencies to permit business land uses in their boundaries while restricting it in adjacent suburbs. Such rent-seeking behavior, supplemented by the betterment levies and non-conforming use approvals, founded Tel Aviv’s rather controversial land use model that has come to be known as “fiscal zoning.” [61]

Development Plan

Tel Aviv’s post-1990s planning doctrine focuses on: (1) immigrant absorption, (2) economic growth and (3) the environment (namely, climate change). For the first time, rather than planning in isolation for the outer ring, the local planning committee began planning at the metro scale. New master plans were produced at national and district levels promoting compact development, curbing sprawl, preserving open space with metro parks, mass public transit planning, and increasing density both in metro core and in the select urban nodes of concentrated business districts (Netanya, Modiin, Ashdod, to name a few). These plans include the NOP 31 (1993), NOP 35 (2005), the Israel 2002 Master Plan, the Tel Aviv Central District Plan 3/21 (2003) and the DOP 5 (2008). [62]

Biodiversity Policy/Planning

NBSAP

The first Israel Biodiversity Action Plan was submitted to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2010. [64] The 2010 plan clearly identifies population growth and subsequent urban expansion as primary threats to biodiversity. The plan led to a series of national reports under the National Biodiversity Monitoring Program aimed at establishing national biodiversity baselines and providing progress reports on the implementation of the NBSAP goals, the most recent of which was released in 2016 and covers the period 2010-2014. [65] The plan heavily emphasizes the need for (1) national scaling of research and monitoring tools to track biodiversity status (including HaMaarag’s National Nature Assessment Program [66] and the flora/fauna national database called BioGIS [67] ), (2) the increase of public awareness around the value of biodiversity, and (3) the introduction of international partnerships promoting interregional biodiversity conservation. [68]

National

The goals of the NBSAP work in tandem with the 2003 Strategic Plan for Sustainable Development in Israel, which demands all ministries establish their own action plans for sustainable growth. [69] Biodiversity policy is set at the national level by the Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection (MoEP). [70] The ministry was established in December 1988 by Government Decision No. 5 and operates on three regional levels, the primary being part of the national government, which is responsible for developing integrated and comprehensive government policy for environmental protection. The ministry is divided into six divisions, or sub-departments, one of which is the natural resources division. This division is then divided into four sub-divisions, one of which is the ‘Open Spaces and Biodiversity’ sub-division. [71] The ministry’s budget and expenditure have steadily increased over time, with large increases occurring in just the last two years . [72]

Regional and Local

The district of Tel Aviv is re s ponsible for implementing its specific environmental needs and projects in suit with the MoEP’s stated environmental goals and broader national policy. One of Tel Aviv’s department of environmental protection’s main missions is the education of municipal government officials about their environmental responsibilities and the need for proper enforcement of environmental laws. Other primary responsibilities include setting environmental conditions for the acquisition of business licenses and overseeing local-level environmental units. [73]

Environmental units also play a big role in the hyper-local implementation of national biodiversity policy. Supported by the MoEP, environmental units are categorized by three types depending on the size and population of a given district: environmental town associations, regional environmental units and municipal environmental units. The 2017-2018 areas of focus for Tel Aviv’s environmental units included air pollution, biodiversity law enforcement, waste treatment, scaling up environmental technologies (primarily related to renewable energy). [74]

Protected Areas

National parks and protected areas in Tel Aviv-Yafo are primarily tourist-related, while a number of wildlife protection facilities exist just beyond the built-out municipality’s boundaries. Such areas include Sheva Tahanot National Park, Yarkon National Park, Ha-banin Garden and Hof Palmahin National Park. [75]

Biodiversity/Landscape Initiatives/Projects

The Tel Aviv University is very active in promoting biodiversity in and around Tel Aviv. The University’s recently opened Steinhardt Museum of Natural History and Israel National Center for Biodiversity Studies partnered to launch the Open Landscape Institute dedicated to “developing policy tools and datasets for promoting protection of land resources and open landscapes in Israel.” [76] The University also includes its own Ecology Campus.

In addition to specific divisions in the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the Ministry of of Foreign Affairs also supports biodiversity conservation projects in Tel Aviv, including monitoring and protecting endemic plant species through the Israeli Gene Bank for Agricultural Crops . [77]

Israel's 1995 afforestation master plan also reflects the country's growing understanding of the importance of forests as both areas of recreation and areas for the conservation of natural plant and animal species. [78] The plan calls for the preservation of 162,000 hectares of woodlands and open areas. It states:

“... [new initiatives are] largely aimed at mapping all of Israel's remaining natural spaces and clarifying their environmental sensitivity. The planning approach which is now being advocated calls for directing development to appropriate areas in ways which will not destroy the ecosystem, the wildlife and the landscape features of each of the small but diverse landscape units in Israel. To provide developers with the necessary conservation information, a preliminary classification of the entire open landscape of the country was carried out and recommendations were made for appropriate levels of protection/development for each landscape unit in accordance with its value, importance, sensitivity and vulnerability.

Concomitantly, the Nature Reserves Authority, in cooperation with the Jewish National Fund, has initiated a project which is meant to help overcome the problem of habitat fragmentation. The new initiative is expected to produce a management plan for the open landscapes of Israel that considers their potential to protect biodiversity. The ecosystem assessment will be based on three guidelines for selecting areas slated for conservation: the presence of endangered species and ecosystems in the area, the biodiversity potential of the area, and the ability of the area to function well in the future based on such criteria as size, connection to other areas with corridors that allow distribution of plants and animals, and the existence of buffer zones around the area. The plan will make a major contribution to the conservation of Israel's diverse ecological systems.” [79]

Protected ecological corridors have surfaced as a primary landscape intervention throughout Israel to allow for more easeful migration for species as climate conditions change in response to global warming. [80] Potential ecological corridors are marked in the Israel Nature and Parks Authority map below:

A number of intergovernmental agreements have recently been established as emphasized by the NBSAP, including the CBD’s Global Strategy for Plant Conservation, the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC), and the FAO’s Global Plan of Action for the Conservation and Sustainable Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. [82]

The MAVA Foundation’s IPAMed project, Conserving Wild Plants and Habitats for People in the South and East Mediterranean, focuses on plant conservation throughout the Mediterranean region [83]

On the development front, Israel has taken a number of actions to embed biodiversity conservation principles into its growth strategy, including:

- Proposal for another 246 nature reserves and national parks

- Inclusion of ecological corridors in development plans

- Creation of the National Plan for Green Growth, which in part aims to reduce environmental impact new development has on biodiversity

- Passage of new development code that requires Environmental Impact Assessments for all major development projects and investments

Finally, the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel (SPNI), [84] and its affiliate organization the IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation (consisting of the Hai-Bar Society, Nature and Parks Authority, SPNI and Middle East Nature Conservation Promotion Association) supports a range of biodiversity projects throughout Tel Aviv-Yafo, and Israel more broadly. [85]

Public Awareness

MoEP and Tel Aviv’s municipal government coordinate certain efforts to increase public awareness of broad environmental sustainability, although biodiversity conservation is not as often discussed as smart resource management and renewable energy production. Political efforts have focused on two programs: (1) Community Gardens, where some neighborhoods established community gardens as habitats for animal species while other have used the space to plan produce and flora; and (2) Sustainable Neighborhoods, which promotes communal and environmental responsibility through public involvement and the advancement of sustainability-related community projects. [86]

Beyond creating local environmental units and launching these two programs, Israeli government agencies and other public institutions have also raised public awareness about the value of biodiversity through the following actions: [87]

- Offerance of ‘activity projects’ to the public (including the Clean Beach program, Love of Nature Week, Green School Program, and others)

- Development of formal biodiversity school curricula

- Creation of a biodiversity educational database at Tel Aviv University

- Opening of the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History (July 2018) by Tel Aviv University to celebrate the nation’s rich history of biodiversity and act as “a call for preservation” of its remaining intact ecosystems [88]

SPNI also carries out a number of environmental and biodiversity education programs throughout Israel and Tel Aviv targeting school children. SPNI also has helped establish community gardens in lower income neighborhoods of South Tel Aviv. [89]

Conclusion

Economic and cultural development is a clear priority for planners and political authorities in Tel Aviv, as the city is the financial capital of the “start up nation” that is Israel and is one of the most powerful global cities in the world. While Tel Aviv residents historically have a close connection with their land, biodiversity conservation takes a backseat in environmental discussions to resource management and climate change action. Generally, environmental sustainability is either understood to be agricultural preservation and productivity or management of natural resources. More recent years have seen an uptick in attention on species extinction and habitat fragmentation in the context of promoting the long term economic value of biodiversity conservation. Given the built out nature and infrastructural demands of Tel Aviv’s economy, Israel’s growing commitment to biodiversity manifests for the most part outside of the municipal boundaries. However, “ despite advances in planning, action on the ground is still too limited to be effective in slowing the rate of loss of threatened species and habitats; it is therefore urgent to move on from the planning phase to the implementation phase .” [90]

[2] World Wildlife Foundation, Southwestern Asia: Along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in Turkey, Jordan, Israel, and Syria,” https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1207 (accessed August 3, 2017).

[3] Richard Weller, “Atlas for the End of the World,” http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com/hotspots/mediterranean_basin.pdf (accessed February 11, 2019).

[4] CEPF. “Mediterranean Basin.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mediterranean-basin.

[5] Richard Weller, “Atlas for the End of the World,” http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com/hotspots/mediterranean_basin.pdf (accessed February 11, 2019).

[6] IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, “About the Mediterranean Ecoregion,” IUCN , https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/content/documents/iucn_mediterranean_programme_2017-2020.pdf , pp. 7

[7] CEPF. “Mediterranean Basin.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mediterranean-basin.

[8] CEPF. “Mediterranean Basin - Species.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mediterranean-basin/species.

[9] CEPF. “Mediterranean Basin - Threats.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mediterranean-basin/threats.

[10] IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, “About the Mediterranean Ecoregion,” IUCN , https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/content/documents/iucn_mediterranean_programme_2017-2020.pdf , pp. 11-12

[11] CEPF. “Mediterranean Basin - Threats.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mediterranean-basin/threats.

[12] CEPF. “Mediterranean Basin.” Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/mediterranean-basin.

[13] “Country Profile: Israel,” World Bank (2017), https://databank.worldbank.org/data/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=ISR (accessed February 12, 2019).

[14] “Country Profile: Israel,” World Bank (2017), https://databank.worldbank.org/data/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=ISR (accessed February 12, 2019).

[15] WWF. “Southwestern Asia: Along the Coast of the Mediterranean Sea in Turkey, Jordan, Israel, and Syria | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1207.

[16] WWF. “Southwestern Asia: Along the Coast of the Mediterranean Sea in Turkey, Jordan, Israel, and Syria | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1207.

[17] WWF. “Southwestern Asia: Along the Coast of the Mediterranean Sea in Turkey, Jordan, Israel, and Syria | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1207.

[18] WWF. “Southwestern Asia: Along the Coast of the Mediterranean Sea in Turkey, Jordan, Israel, and Syria | Ecoregions.” World Wildlife Fund. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/pa1207.

[19] “Eastern Mediterranean Conifer-Sclerophyllous-Broadleaf Forests.” DOPA Explorer. Accessed August 12, 2019. https://dopa-explorer.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecoregion/81207.

[20] Burke, A. A., & Peilstöcker, M., “The Egyptian Fortress in Jaffa,” Popular Archeology , (2013).

[21] Shamir, R, “Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine,” Stanford University Press , (2013).

[22] Shamir, R, “Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine,” Stanford University Press , (2013).

[23] Barron, J., “Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922,” Greek Convent Press , (1922), pp. 6.

[24] Municipality of Tel Aviv-Yafo, “A Brief History of Tel Aviv,” Tel Aviv Nonstop City, https://www.tel-aviv.gov.il/en/abouttheCity/Pages/history.aspx (retrieved February 12, 2019).

[25] Wetler, V. M, “The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes,” In Israel Studies Vol. 14, No. 3, Tel Aviv: Tel-Aviv Centenary , (2009), pp. 98.

[26] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Nature Conservation in Israel,” State of Israel, (2013), https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/IsraelExperience/AboutIsrael/Spotlight/Pages/Nature%20Conservation%20in%20Israel.aspx (retrieved February 13, 2019).

[27] Wetler, V. M, “The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes,” In Israel Studies Vol. 14, No. 3, Tel Aviv: Tel-Aviv Centenary , (2009), pp. 106.

[28] Razin, E, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” In I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012), pp. 161.

[29] Razin, E, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” In I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012), pp. 149.

[30] Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, “Threats to Biodiversity,” State of Israel (2012), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/env_topics/biodiversity/ThreatsToBiodiversity/Pages/default.aspx

[31] IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, “About the Mediterranean Ecoregion,” IUCN , (2019), https://www.iucn.org/regions/mediterranean/about

[32] Marcos Valderrábano, Teresa Gil et al, “Conserving wild plants in the south and east Mediterranean region,” IUCN (2018), https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2018-048-En.pdf

[33] IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, “About the Mediterranean Ecoregion,” IUCN , https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/content/documents/iucn_mediterranean_programme_2017-2020.pdf , pp. 10

[34] Marcelo Sternberg, Ofri Gabay, Dror Angel, et al. Impacts of Climate Change on Biodiversity in Israel: an expert assessment approach. August 2014. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. https://m.tau.ac.il/lifesci/departments/plant_s/members/sternberg/documents/Sternberg%20et%20at%20REC%202014.pdf

[35] Marcelo Sternberg, Ofri Gabay, Dror Angel, et al. Impacts of Climate Change on Biodiversity in Israel: an expert assessment approach. August 2014. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. https://m.tau.ac.il/lifesci/departments/plant_s/members/sternberg/documents/Sternberg%20et%20at%20REC%202014.pdf

[36] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Nature Conservation in Israel,” State of Israel, (2013), https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/IsraelExperience/AboutIsrael/Spotlight/Pages/Nature%20Conservation%20in%20Israel.aspx (retrieved February 13, 2019).

[37] Global Forest Watch, “Tel Aviv, Israel Dashboard,” (2017), https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/ISR/7?category=forest-change (retrieved May 1, 2019).

[38] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Nature Conservation in Israel,” State of Israel, (2013), https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/IsraelExperience/AboutIsrael/Spotlight/Pages/Nature%20Conservation%20in%20Israel.aspx (retrieved February 13, 2019).

[39] Richard Weller, “Atlas for the End of the World,” http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com/hotspots/mediterranean_basin.pdf (accessed February 11, 2019).

[40] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Nature Conservation in Israel,” State of Israel, (2013), https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/IsraelExperience/AboutIsrael/Spotlight/Pages/Nature%20Conservation%20in%20Israel.aspx (retrieved February 13, 2019).

[41] Atlas of Urban Expansion, “Country Profiles: Tel Aviv,” Retrieved from The Atlas of Urban Expansion (2016) , http://www.atlasofurbanexpansion.org/cities/view/Tel_Aviv

[42] Atlas of Urban Expansion, “Country Profiles: Tel Aviv,” Retrieved from The Atlas of Urban Expansion (2016) , http://www.atlasofurbanexpansion.org/cities/view/Tel_Aviv

[43] Atlas of Urban Expansion, “ Country Profiles: Tel Aviv,” Retrieved from The Atlas of Urban Expansion (2016) , http://www.atlasofurbanexpansion.org/cities/view/Tel_Aviv

[44] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012).

[45] K Kloosterman, “Changes in the air for Ajami: A mixed Arab-Jewish neighborhood in Jaffa balances itself between rundown remnants of old-world charm and upscale gentrification,” The Jerusalem Post (2009).

[46] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012).

[47] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012).

[48] Department of Landscape and Biodiversity, “Israel’s National Biodiversity Plan” State of Israel, ( 2010), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/env_topics/biodiversity/Documents/NationalBiodiversityPlan2010.pdf

[49] Naomi Caplan, “Refugees in Israel,” ARDC Israel (2017), https://www.ardc-israel.org/refugees-in-israel

[50] Ilan Lior, “ Asylum Seekers Deported from Israel to Rwanda Warn Those Remaining: ‘Don’t Come Here’,” Haaretz (2018), https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/asylum-seekers-who-left-israel-for-rwanda-warn-those-remaining-don-t-1.5785996

[51] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs , “THE STATE: Local Government,” State of Israel , (2013), https://mfa.gov.il/mfa/aboutisrael/state/pages/the%20state-%20local%20government.aspx# (retrieved February 12, 2019).

[52] Municipality of Tel Aviv-Yafo, “Welcome Message from Mayor Ron Huldai,” Tel Aviv Nonstop City, https://www.tel-aviv.gov.il/en/abouttheMunicipality/Pages/mayor.aspx (retrieved February 12, 2019).

[53] Municipality of Tel Aviv-Yafo, “Tel Aviv in Numbers,” Tel Aviv Nonstop City, https://www.tel-aviv.gov.il/en/abouttheCity/Pages/CityinNumbers.aspx (retrieved February 12, 2019).

[54] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs , “THE STATE: Local Government,” State of Israel , (2013), https://mfa.gov.il/mfa/aboutisrael/state/pages/the%20state-%20local%20government.aspx# (retrieved February 12, 2019).

[55] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012). P 159-160.

[56] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012). P. 159

[57] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012). P. 160

[58] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012). P. 159

[59] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012). p . 164

[60] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012). P. 164

[61] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012). P. 160

[62] Eran Razin, “Deconcentration in the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area,” in I. Vojnovic, Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Michigan State University Press , (2012).

[63] Nektarios Chrysoulakis, Christian Feigenwinter et al., “A Conceptual List Indicators for Urban Planning and Management Based on Earth Observation,” In International Journal of Geo-Information 3(3):980-1002, ResearchGate (July 2014), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264331466_A_Conceptual_List_of_Indicators_for_Urban_Planning_and_Management_Based_on_Earth_Observation

[64] “Search NBSAPs and National Reports,” CBD , https://www.cbd.int/nbsap/search/default.shtml

[65] “Israel’s Fifth National Report to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity,” Ministry of Environmental Protection (2016), http://www.sviva.gov.il/infoservices/reservoirinfo/doclib2/publications/p0801-p0900/p0828.pdf

[66] “HaMaarag - Israel’s National Nature Assessment Program ,” HaMaarag (2019), http://www.hamaarag.org.il/en/content/inner/hamaarag-israel%E2%80%99s-national-ecosystem-assessment-program

[67] BioGIS, “Israel’s Diversity of Animals and Plants,” Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2019), http://www.biogis.huji.ac.il/

[68] Department of Landscape and Biodiversity, “Israel’s National Biodiversity Plan” State of Israel, ( 2010), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/env_topics/biodiversity/Documents/NationalBiodiversityPlan2010.pdf

[69] Department of Landscape and Biodiversity, “Israel’s National Biodiversity Plan” State of Israel, ( 2010), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/env_topics/biodiversity/Documents/NationalBiodiversityPlan2010.pdf

[70] Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, “About Us,” State of Israel (2012), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/AboutUs/Pages/AboutUs.aspx#GovXParagraphTitle3

[71] Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, “Ministry Structure,” State of Israel (2012), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/AboutUs/MinistryStructure/Pages/Default.aspx

[72] Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, “Ministry of Environmental Protection Budget,” State of Israel (2012), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/AboutUs/Pages/Budget.aspx

[73] Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, “Ministry Structure,” State of Israel (2012), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/AboutUs/MinistryStructure/Pages/Default.aspx

[74] Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, “Biodiversity,” State of Israel (2012), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/env_topics/biodiversity/Pages/Biodiversity-default.aspx

[75] “National Parks and National Reserves,” Israel Nature and Parks Authority (2017), https://www.parks.org.il/en/

[76] “About Us,” Open Landscape Institute, http://www.deshe.org.il/?CategoryID=206

[77] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Nature Conservation in Israel,” State of Israel, (2013), https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/IsraelExperience/AboutIsrael/Spotlight/Pages/Nature%20Conservation%20in%20Israel.aspx (retrieved February 13, 2019).

[78] KKL-JNF Staff, “Afforestation in Israel,” The Jerusalem Post (2011), https://www.jpost.com/Green-Israel/People-and-The-Environment/Afforestation-in-Israel

[79] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Nature Conservation in Israel,” State of Israel, (2013), https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/IsraelExperience/AboutIsrael/Spotlight/Pages/Nature%20Conservation%20in%20Israel.aspx (retrieved February 13, 2019).

[80] Marcelo Sternberg, Ofri Gabay, Dror Angel, et al. Impacts of Climate Change on Biodiversity in Israel: an expert assessment approach. August 2014. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. https://m.tau.ac.il/lifesci/departments/plant_s/members/sternberg/documents/Sternberg%20et%20at%20REC%202014.pdf

[81] Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/env_topics/biodiversity/Pages/Biodiversity-default.aspx

[82] Marcos Valderrábano, Teresa Gil et al, “Conserving wild plants in the south and east Mediterranean region,” IUCN (2018), https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2018-048-En.pdf

[83] Marcos Valderrábano, Teresa Gil et al, “Conserving wild plants in the south and east Mediterranean region,” IUCN (2018), https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2018-048-En.pdf

[84] IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, “About the Mediterranean Ecoregion,” IUCN , (2019), https://www.iucn.org/regions/mediterranean/about

[85] “Tel Aviv-Yafo,” Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel , http://natureisrael.org/Where-We-Work/Tel-Aviv

[86] Municipality of Tel Aviv-Yafo, “Smart Energy Promotion,” Tel Aviv Nonstop City, https://www.tel-aviv.gov.il/en/abouttheCity/Pages/SmartEnvironment.aspx (retrieved February 12, 2019).

[87] Israel Ministry of Environmental Protection, “Aichi Biodiversity Targets,” State of Israel (2012), http://www.sviva.gov.il/English/env_topics/biodiversity/AichiTargets/Pages/default.aspx

[89] “Tel Aviv-Yafo,” Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel , http://natureisrael.org/Where-We-Work/Tel-Aviv

[90] Marcos Valderrábano, Teresa Gil et al, “Conserving wild plants in the south and east Mediterranean region,” IUCN (2018), https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2018-048-En.pdf